We ask you, brothers, with regard to the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ and our assembling with him, not to be shaken out of your minds suddenly, or to be alarmed either by a “spirit,” or by an oral statement, or by a letter allegedly from us to the effect that the day of the Lord is at hand. Let no one deceive you in any way. For unless the apostasy comes first and the lawless one is revealed, the one doomed to perdition, who opposes and exalts himself above every so-called god and object of worship, so as to seat himself in the temple of God, claiming that he is a god—do you not recall that while I was still with you I told you these things? And now you know what is restraining, that he may be revealed in his time. For the mystery of lawlessness is already at work. But the one who restrains is to do so only for the present, until he is removed from the scene. And then the lawless one will be revealed, whom the Lord [Jesus] will kill with the breath of his mouth and render powerless by the manifestation of his coming, the one whose coming springs from the power of Satan in every mighty deed and in signs and wonders that lie, and in every wicked deceit for those who are perishing because they have not accepted the love of truth so that they may be saved. Therefore, God is sending them a deceiving power so that they may believe the lie, that all who have not believed the truth but have approved wrongdoing may be condemned. But we ought to give thanks to God for you always, brothers loved by the Lord, because God chose you as the firstfruits for salvation through sanctification by the Spirit and belief in truth.

—2 Thess 1-12

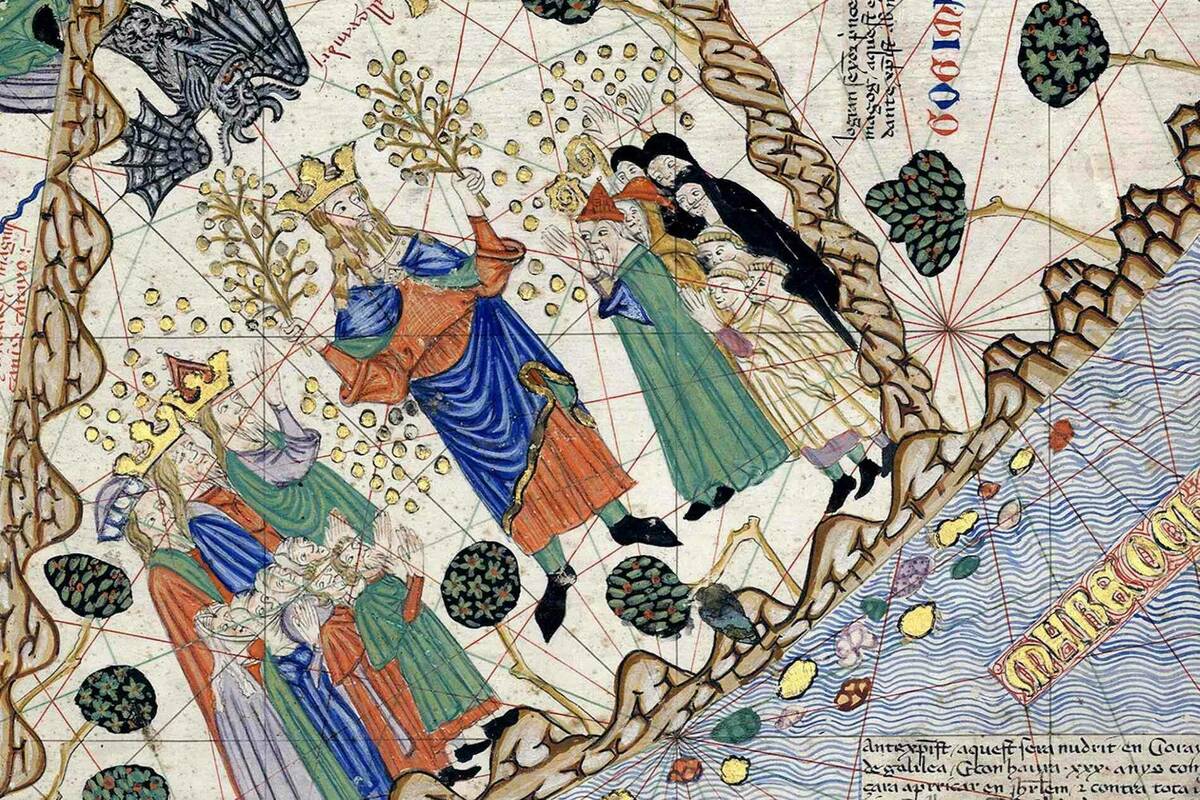

What does Paul have to do with Antichrist? In Constructing Antichrist I argue that the Western medieval doctrines of Antichrist and the Last Days cannot be understood rightly apart from the development of Latin traditions of New Testament exegesis. 2 Thessalonians—a brief but important Pauline text in New Testament apocalyptic literature—was a center of speculation and debate about matters apocalyptic in the early Church. Thus, the way one decides to interpret Paul shapes the way one understands Antichrist. Will the fall of Rome signal the End of Time? Is Antichrist to be a single individual in the future, or is it better to understand it in the spiritual sense, “the Body of Antichrist” (evil people) within the “Body of Christ” (the Church) right now? Medieval Christians wrestled with these questions by grappling both with 2 Thessalonians itself and with the traditions of interpretation that preceded them. By the twelfth century, the tradition of reflection distilled from the many and various early interpretations a synthetic understanding of Antichrist and the End as both present and to come, both historical and spiritual. In my book, I follow the process of distillation as it occurs through the formal genre of commentary. Using the tools of scriptural commentary, medieval scholars aimed to correlate the questions they brought to the text with the many possible senses of the text and the words of the Fathers on the text and synthesize them into one intelligible whole. Commentaries on 2 Thessalonians, then, provided the “architecture” for the developing doctrine of Antichrist.

It should be no surprise to any student of early medieval literature, and especially of early medieval exegesis, that the fruit of medieval thinking was a synthesis of earlier patristic authorities. What I have studied across eight centuries is the emergence of an early medieval exegetical tradition. Early medieval exegetes constructed a reading of 2 Thessalonians that united and synthesized opposed positions, and thus arrived at a complex new understanding of the presence and absence, the immanence and imminence, of the apocalyptic Adversary. But such a synthesis was not simply the product of some medieval deference to authority or predisposition to harmonizing apparent opposites. If these traits are truly to be found in the intellectual life of the Middle Ages, they do not suffice to explain away the synthesis of presence and anticipation in the 2 Thessalonians commentary tradition. The synthetic readings I have identified represent efforts to discern the sense and structure of Christian eschatology, which is always rooted in the past (in the life and identity of Jesus), but projected toward the future (toward the consummation of time and history in the end). In other words, these synthetic readings give shape to medieval Christian life and history as suspended between the resurrection of Christ and the heavenly Jerusalem. In so doing, they preserve the dynamic tension of the New Testament’s apocalyptic symbols and develop Pauline eschatology in greater detail.

The Early Medieval Synthesis: Summarizing the Chronological Argument

The roots of the exegetical tradition around 2 Thessalonians are sunk in the soil of conflict. In the late fourth and early fifth centuries, the commentaries of Ambrosiaster, Pelagius, and Theodore of Mopsuestia, together with Jerome’s letter to Algasia, express what I have taken to be the “mainline eschatology” of the ancient Christian Church. Though there are some differences of opinion upon the details of the end, these four texts share the general conviction that the “rebellion” will be a distinct historical event in the future and that Antichrist will be a concrete individual acting in history.

But this general consensus faced a formidable adversary. Augustine of Hippo accuses those who maintain such a realist apocalyptic eschatology of “presumption.” To pretend to know clearly the details of the events of the end is to reach beyond the grasp of human knowledge. One can know only the essential facts of the coming of Antichrist and the end. With Tyconius, Augustine offers an alternative reading of eschatology that posits that the importance of texts such as 2 Thessalonians lay in their immanent spiritual meaning, as an assessment of the divided body of the present Church in which there are many antichrists. While dogmatic summaries of the essential events of revealed eschatology are permitted, they are clearly subordinated to the immanent moral understanding of eventual judgment.

By the fifth century, then, it is clear that opinion upon matters eschatological is divided. The majority of early Christian exegetes of 2 Thessalonians believe that the letter offers a historical account of the end of time and the coming Antichrist. Consequently, they endeavor in their commentaries to understand the particular historical details to which the letter seems to refer. Against these figures stands Augustine. While he shared the support of thinkers such as Jerome in opposing a millennialist reading of the Apocalypse, and while he, too, will agree to the most general outline of “eschatological events,” including the rise and the fall of Antichrist, he seems to stand alone (with only the heterodox Tyconius) in his consistent resistance to any detailed realist eschatology. Nevertheless, because of his position as the preeminent Doctor of the Western Church, his opinion would hold formidable authority for the centuries that followed.

Early medieval exegetes quarry the patristic writings—commentaries, letters, sermons, and treatises—for any reference to 2 Thessalonians or the figures and doctrines to which it refers. These comments form the building blocks, the bricks and mortar, from which early medieval exegetes construct their own commentaries, and, in so doing, construct the symbol of Antichrist himself. These opinions—of Ambrosiaster, Pelagius, Jerome, Augustine, Theodore, and even Gregory—together form what Pierre Hadot has called the “topics” of an exegetical tradition, the “formulae, images, and metaphors that forcibly impose themselves on the writer . . . in such a way that the use of these prefabricated models seems indispensable to them in order to be able to express their own thoughts.” The figure of Antichrist that emerges—both the single historical figure awaited by Ambrosiaster and the community of wickedness hidden within the Church found in Tyconius, Augustine, and Gregory—is complex and suspended through time.

The greater part of early medieval interpretive effort is devoted to that future figure of Antichrist; the Tyconian reading receives its most vivid portrayal in Gregory and thereafter is consistent in its admonition to believers that they should avoid evil lest they be part of the body of Antichrist. Medieval exegetes mostly comb the patristic tradition to arrive at an understanding of the signs of the end and Antichrist. To this primary reading, most fuse elements of the Augustinian interpretation, but always as yet another meaning of the text, not in opposition to the rest. Augustine’s seemingly reluctant admission that the Scriptures may refer to a sequence of historical events in the end is seized by early medieval exegesis as a point of harmony that dulls his polemical edge.

For example, Gregory the Great’s exegetical work includes several thematic improvisations upon the Tyconian/Augustinian image of the body of Antichrist. But Gregory incorporates this spiritual reading into an apocalyptic fugue, a contrapuntal play of presence and anticipation that announces the imminence of Antichrist’s arrival through the signs of his immanence. The flourishing of the body of Antichrist within the Church can only provide further testimony to the approach of its head in the last days. Gregory, the “last of the Latin Fathers” points the way to early medieval eschatological exegesis, insofar as he integrates the Tyconian/Augustinian imagery into a predominantly realistic apocalyptic account.

Two and a half centuries later, Carolingian exegesis of 2 Thessalonians carries an echo of Gregory’s apocalyptic fugue, holding together Antichrist’s two bodies—the social body of the present and the individual body to come. Using their distinctive exegetical methods, wherein commentary consists of layering patristic excerpts to construct a new synthetic whole, Carolingian exegetes such as Rabanus Maurus and Sedulius Scotus continue to incorporate the Augustinian position into a realist reading of the text drawn from Theodore and Pelagius, respectively. Florus of Lyons makes no attempt to integrate particular patristic opinions in any way, since he prefers to produce independent summaries of the opinions of Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory. Nevertheless, Florus appears willing to summarize both the apocalyptic realism of Jerome and the anti-apocalyptic reading of Augustine, without any apparent sense of opposition between them. For all of these thinkers, it is not at all problematic to place the two positions side-by-side.

Haimo of Auxerre presents perhaps the most interesting exception to this tendency among the Carolingians, since he makes no attempt in his 2 Thessalonians commentary to include an Augustinian perspective. Instead, he offers only realist apocalypticism in his Pauline commentary, saving the Augustinian/Tyconian interpretation for his commentary on the Apocalypse. Haimo’s departure from the general integrative approach to 2 Thessalonians in fact reflects a further development in the early medieval synthetic approach to apocalyptic matters. Haimo accepts the “peaceful coexistence” of the apocalyptic realist and Latin spiritual traditions of interpretation, but distinguishes between them on the basis of genre. The spiritual interpretation is appropriate to the visionary text of the Apocalypse, while the apocalyptic realist interpretation fits the more practical catechetical purposes of Paul. In Haimo, then, we find harmony between the traditions, but in a different key. In all cases, what is distinctive about the Carolingian commentaries is the simultaneity of presence and anticipation, together with a deep reluctance to predict the end. This combination of elements, I have argued, is not simply a consequence of their methods of harmonizing the Fathers. Rather, it both fosters and reflects a non-predictive psychological imminence characteristic of early medieval apocalypticism, which feeds the early medieval imagination with apocalyptic imagery and rhetoric. The 2 Thessalonians tradition testifies to the persistent presence of apocalypticism that may or may not have intensified around key dates or events, but never disappears from the cultural imagination even when imminent “prophecies pass away” (1 Cor 13:8).

In the midst of the renewal and reform movements of the eleventh century, scholarship on 2 Thessalonians takes on a new face in the schools of France. These early scholastic commentaries pay close attention to the “rhetorical situation” of Paul’s letter: to whom he wrote, why he wrote, the form of his argument. Consequently, their commentaries, like Haimo’s, prefer the apocalyptic realist reading of the text: Paul wrote to the Thessalonian community to give the signs of the end. Thus, even when Lanfranc cites Augustine, he edits the text in such a way that the Father’s statements seem to support, rather than contradict, the traditional realist account.

With the Glossa Ordinaria and Peter Lombard’s commentary in the early twelfth century, this early medieval consensus begins to dissolve. Through a more thorough retrieval of the Augustinian sources, these two commentaries suggest that patristic interpretations of the text may not be so harmoniously integrated. The glossator simply presents the two theological positions in a dialectical fashion, without attempting to resolve the argument or harmonize the sources. Peter Lombard, on the other hand, advocates the Augustinian position, thereby upsetting the balance found in earlier sources between presence and expectation. To a certain extent, what Peter has done is to retrieve from Augustine the tension and opposition between readings that the early medieval tradition had united. In Peter Lombard’s commentary on 2 Thessalonians, we see both the last evidence of the early medieval commentary tradition and the first evidence of its demise. While Peter’s work retains the form of the early medieval commentary—a running text, inclusive of a variety of patristic and medieval opinions upon it—the argument of his reading is deliberately opposed to the consensus of opinion throughout the early medieval tradition. Peter’s commentary, though formally consistent with the early medieval exegetical tradition, effectively subverts that tradition with a strategic retrieval and re-deployment of the opinions of Saint Augustine.

This is not to say that Peter Lombard ends realist apocalyptic speculation. In fact, even before the Joachimist “revival” of apocalyptic speculation, one finds ample evidence of twelfth-century interest in apocalyptic matters. For example, there are at least forty surviving manuscripts of Adso’s treatise on Antichrist, under various pseudonyms, from the twelfth century, showing some considerable interest in the apocalyptic Adversary. What we find in Peter Lombard’s commentary is rather the end of a general consensus on the basic sense of the text and, perhaps, then, the end of the psychological imminence that balances presence and expectation of Antichrist. After Peter, writers choose whether to accept the traditional realist reading or to reject it as Peter had. What we see with Peter Lombard, then, is the beginnings of a divide between what Marcia Colish has called “monastic” and “scholastic” eschatology. For Colish, “monastic” eschatology “anxiously seeks to answer questions arising from the worries of people concerned with what is going to happen to their own souls . . . during the coming last days.” It “also reflects a tendency to politicize the idea of Antichrist . . . sometimes connecting this theme with the tradition of Nero as Antichrist.” “Scholastic” theologians, on the other hand, “have no hortatory or visionary concerns, and they take a dim view of apocalyptic speculation.” If these categories are understood as heuristic rather than denotative, with the understanding that there are “scholastic” monks and “monastic” school-trained friars, she is certainly right to identify a parting of the ways, a division that we can recognize in Peter Lombard. But it is important to note that the monastic writers are not just those “who write in light of popular belief.” They draw on a long and well-developed tradition of thought, one to which the 2 Thessalonians commentaries bear witness. It is the scholastic writers (and only some of them) who recover the minority position of Augustine or disregard apocalyptic symbols altogether. “Scholastic” eschatology, at least as represented by Peter Lombard and those dependent upon him, represents real innovation in the tradition of eschatological reflection.

The Persistence of Apocalypticism: Implications for the History of Theology

Early medieval exegesis of 2 Thessalonians challenges still-prevalent assumptions about the history of medieval theological eschatology. Traditionally, the history of apocalyptic eschatology in the early Middle Ages has followed the contours of a tragic “decline-and-fall” plot line. While the early Fathers of the Church had a vivid sense of the imminence of the Lord’s coming, the tides of time gradually eroded these apocalyptic convictions. With Augustine, the story goes, apocalyptic speculation receives a thorough dressing-down as an area of serious theological reflection. After Augustine, apocalyptic texts are consistently interpreted in a spiritual fashion, as an allegory of the Church in the present time. Thus Stephen D. O’Leary’s engaging study of the rhetoric of apocalyptic argument still presumes that the “allegorical understanding of prophecy developed out of necessity in the centuries after the Apocalypse was produced.” O’Leary’s argument continues:

With the passage of time and the conversion of the empire to Christianity, however, the text [the Apocalypse] became more and more difficult to interpret as a set of historical predictions: the prophesied End had failed to materialize, and the former Antichrist now convened ecclesiastical councils and used his troops to suppress heresy. . . . Under these circumstances, the drama of the End came to appear as an allegorical representation of the Church’s struggle against its enemies in all ages.

The allegorical understanding of Augustine is taken to be the natural and inevitable response to the frustrated expectations of the early Church. After Augustine, Christian theology abandoned apocalyptic realism for allegory, and, its seems, lost its apocalyptic edge. As the story often goes, the aversion to apocalyptic speculation and this allegorical tradition of interpretation dominated Christian eschatology until Joachim of Fiore’s prophetic, historical interpretation of the Apocalypse revived the enthusiasm of the early Church in the twelfth century.

This reading of the early Middle Ages, or at least of early medieval high culture, as essentially post-apocalyptic, has been challenged by scholars such as Richard Landes and Johannes Fried. They have recovered hints and clues of apocalyptic movements at certain key times in medieval history. Like them, to paraphrase Mark Twain, I believe the death of apocalypticism in the Middle Ages has been greatly exaggerated. The force of Augustine’s spiritual and ecclesial reading of the Apocalypse, while significant, simply cannot overcome the realism of the medieval apocalyptic imagination. For Landes and Fried, this suggests a hidden history of apocalyptic enthusiasms, one subdued or erased by more conservative clerical elites. But the 2 Thessalonians tradition suggests that apocalyptic realism is both more pervasive and less subversive than any particular imminent millennialism, whether of A.M. 6000, A.D. 1000, A.D. 1033, or some other. The apocalyptic imagination is a constant cultural fact in the Middle Ages, and its essential vocabulary is preserved and explicated in the 2 Thessalonians tradition. But if apocalyptic hope and anxiety broke out in Rabanus Maurus’s Fulda or in Lanfranc’s Bec, no particular traces of this outbreak show up in their commentaries. The most we can theorize, I think, is an apparent change of temperature in medieval apocalyptic thought in the years after 1000, connected intimately to the Gregorian reform movement and reflected in the commentaries of Lanfranc and Bruno.

But even these readings are shaped as much by the “restless traditionality” of the commentaries that precede them, and so the terms of discussion remain rather constant throughout the early medieval period. The 2 Thessalonians tradition offers a reading of apocalypticism that is neither millennialist prophesying nor ahistorical allegorizing. The reading that emerges preserves a sense of God’s presence and activity in history while at the same time protecting that sense from erratic predictive fantasies. Antichrist always threatens from the future as the embodiment of the human rejection of the Gospel, and is always slain in Christ’s triumphant return. Through the ongoing development of the doctrinal portrait of Antichrist, the dramatic character of the apocalyptic imagination preserves the Christian “sense of an ending” that invests human life “in the middest” with meaning and direction. In so doing, the 2 Thessalonians tradition explicates a tradition of Christian eschatology that can be found throughout the New Testament.

New Testament scholars since Cullmann and Jeremias have long discussed the nature of the Kingdom of God in the parables of Jesus as “eschatology in the process of realization” or “proleptic eschatology.” In the preaching of Jesus, the Kingdom of God is both “already” and “not yet.” This mutuality of the “already” and the “not yet” is constitutive of the classical Christian understanding of time and history. What some scholars have worried about with regard to apocalyptic literature as a genre is a perceived tendency to relieve the tension in favor of the future. That is, in the traditional account, apocalyptic texts find it difficult to discern signs of the Kingdom already at work in the world; instead, they view this age as wholly wicked and await the catastrophic intervention of the Kingdom of God as the age to come. However, such bold-faced dualistic apocalyptic eschatology does not really appear in the New Testament, since faith in Christ seems to obviate the radical pessimism of some earlier apocalyptic traditions. Our initial discussion of 2 Thessalonians, where the already/not yet dynamic is seen in the presence and anticipation of both the “restrainer” and the “iniquity” that it/he restrains, is one case among several. Canonical Christian apocalyptic eschatology retains the tension between the already and the not yet.

The 2 Thessalonians tradition explicates this tension further. The realist reading preserves the “not yet” of Christian anticipation. The elements of the Latin spiritual reading wove the sense of God’s presence in history into the fabrics of the individual Christian’s moral life and the life of the Church. Taken as a whole, the synthetic medieval reading represents a sober reflection upon the useful theological elements of the doctrines of Antichrist and the end. In effect, the early medieval tradition sketches the limits and possibilities of what one might call “orthodox” apocalyptic expectation. It may be—though I can only suggest it as something worth further inquiry—that the dissolution of this synthesis is more catalyst than response to the appearance of more radical apocalypticisms in the later Middle Ages. Apocalypticism is persistent; attempts—whether medieval or modern—to erase it from “respectable” Christianity may simply lead to its springing up in more radical and volatile forms outside the mainstream. Regardless, such tensive apocalypticism is a consistent feature of early medieval exegesis of 2 Thessalonians.

In the end, scholars such as Jaroslav Pelikan are right, but only partly so, to speak of “the apocalyptic vision and its transformation” in the early Church as “nothing less than the decisive shift from the categories of cosmic drama to those of being, from the Revelation of St. John to the creed of the Council of Nicea.” But neither is it the case that the withdrawal from imminent expectation is an elite conservative conspiracy of silence against popular imminent millennialism. Indeed, the cosmic drama of the Parousia was less and less the focus of Christology, sacramental theology, and other areas of theological speculation. But if the drama was no longer center stage, the set was never struck. The apocalyptic structure of history, the expectation of the Adversary, and the “psychological imminence” of the end became the backdrop against which these other theological elements were rehearsed. Apocalypticism was a persistent element of the medieval imagination, made all the more persistent by its release from predictive imminence or millennialism. For the first millennium of Christianity, early medieval theologians continued to “live in the shadow of the Second Coming” and to ponder what that Second Coming might entail.

So Antichrist was alive and well in the early Middle Ages, both as the immanent presence of evil and as the coming evil one. In the 2 Thessalonians tradition, apocalyptic realism provides the most fertile ground for speculation, debate, and development, but it is always balanced or supplemented in some way by the Augustinian spiritual interpretation. It is at the fault line between the two fields—in the encounter between apocalyptic realism and spiritual exegesis—that a distinctive early medieval apocalypticism is born. The double sense of Antichrist’s presence in the midst of the Church and his historical persona still to come produces just the sort of non-predictive, psychological imminence that helps create the distinctive medieval ethos of “Christianitas,” or “Christendom.” The 2 Thessalonians tradition documents the development and longevity of this ethos in microcosm. Through the words of Paul, exegetes across the first millennium of the Christian Church constructed a theological portrait of Antichrist, and they remained convinced, with the Apostle, that the apocalyptic Adversary was still to come, and yet, paradoxically, already at work in their midst.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This article is excerpted from Constructing Antichrist: Paul, Biblical Commentary, and the Development of Doctrine in the Early Middle Ages (Catholic University of America Press, 2014). All rights reserved.