Halfway through Willa Cather’s novel Shadows on the Rock, the protagonist Monsieur Auclair, a French apothecary living in Quebec, meets an old friend Fr. Hector. Though a relatively minor character in the overall novel, Fr. Hector’s appearance teaches something essential to the Christian life. Fr. Hector is cultured and intelligent, “fond of the decencies and elegancies of life,” but has spent the last few years in the middle of the Canadian wilderness. When he returns to his friend, he is overjoyed. “Only solitary men know the full joys of friendship,” he responds. Upon receiving the gift of a dinner, he says, “If one had not been through little experiences of that kind [he almost starved to death], one would not know how to enjoy a dinner such as this.”

The wilderness has taught Fr. Hector something, and it is one of the lessons that the Church attempts to teach us with her weekly and seasonal penances. Yet we have forgotten this wisdom. This is not only evinced by the near total lack of meaningful penitential practices in most Christian’s lives, but also by the near silence from the pulpit. The Church still has penitential seasons, yet the most we hear about them is a reminder that they are coming and obligatory. It is a shame. The Church does not bid us to do penance from some blind adherence to tradition. She does not bid us to do penance primarily as a punishment for our sins. She bids us to do penance as a training in love, a training in how to feast. Put simply, penance trains us to rejoice properly in God, ourselves, and our neighbors. This wisdom thus prepares us for the heavenly feast, but also prepares us to enjoy the feast of this world. In a fundamental sense, it is God and the world, or nothing. We either prepare ourselves for the heavenly kingdom, and ipso facto learn to enjoy this world, or we do neither. In other words, a penitential season is not simply a memoria passionis, but is also an expression of the deep anthropological wisdom given to us in revelation.

To see the wisdom in having periodic penitential days and seasons, we must first understand two things about creation. The first is that all creation is a participation in God and reflects his goodness. Because all created things are participations in the perfection of God, when God produces creatures they point back to him. When we notice and seek the goods of this world, we are noticing and seeking a dim reflection of the supereminent goodness of their source, God. This is the sacramental logic of creation–God is made present in and through his creation. Second, the things of creation are not simply ordered to God but also to each other by their distinct and different degrees of participation in God. Plants, for example, are ordered ultimately to God and flourishing, but in a lesser way to human use. Hence, when we come to the good things of this world, we are not coming to a blank slate but an ordered whole which is a product of God’s will. Put simply, Genesis teaches us two things about finite goods: First, they are participations in God’s goodness. Second, they are ordered to each other and ultimately to God.

This order of creation governs our loves. In other words, remove any good from its reference to God or its place in creation and it will lose a fundamental aspect of its goodness. Many things are good when ordered to a higher good and in moderation which cease to be good when not so ordered. Name the addiction: food, technology, honor, sex, money, power, comfort, etc. We are constantly tempted to overvalue lower goods, to remove goods from their order to other humans or the common good, and especially to remove them from their order to God. Even if we do not love lower goods too much or remove them from their order to God, we have the unique inability to be grateful for something that is easy to obtain, securely held, and abundant. In other words, we cease to see things as good which are in fact good. Evidence of this is that joy is supposed to follow when we obtain the good we love. Do we have joy at the good things of this world? Who is not guilty of a failure in gratitude to others and to God? We depend on others for almost everything and on God for everything, even our very existence. Our response is lukewarm, at best. In other words, we exist in a world saturated with goodness but have no joy. Something is wrong.

Enter penance. Intermittent and seasonal penances combat all these problems. Penance is a way of training our loves to adhere to the logic of creation. In penance we go without what is good. This could be a good which you seek in a disordered way (i.e. sinfully), a good you think you might be pursuing in a disordered way, a good you are not seeking sinfully but fail to appreciate fully, or even a good you are not seeking sinfully and fully appreciate. Each of these, even the last, moves us to rightly order our loves in accordance with God’s creation.

The first, giving up the good we sinfully seek, is obviously the most fundamental and serious. It serves as an actual remedy for present sin. It is not really meant for penitential seasons, but for every day. For goods we pursue in a sinful way, we must cease to pursue them or correct the disorder in our pursuit. By doing this we offer a difficult and fitting reparation for the disordered love of that good. The last, giving up some good we seek and enjoy rightly, serves to remind us of our true home and help us to focus on God. In this way, penance is an aid to prayer and a remedy for potential future sin. The middle two serve as correctives and tests of our love. We might be pursuing a good in a disordered way, so we give it up. A person can tell how much he loves something by the degree of desire born with its absence. Depending on the good, serious desire could bespeak over attachment to that good. Without this type of penance, we can easily trick ourselves into thinking we do not have idols in our lives. Finally, going without a good for a time can remind us of how good something really is so that we may fully enjoy it when we return to it.

Pursuing the goods of this world in a rightly ordered way not only helps us love those goods and rejoice in them, it also helps us live in community and love our neighbors. Over-attachment to the goods and comforts of this world binds us; we are not free to love persons because we love things too much. We are not free to give up our power, prestige, wealth so that the goods God has given us may reach their intended end. Most especially, when we love ourselves in a disordered way, we are not free to love ourselves, our neighbor, or the goods of this world in the right way. We order all things to ourselves as if that is what God intends in creation. Far from it. This is a radical inversion of the logic of creation. In our communities and day to day lives, loving lower goods more than higher is a primary source of contention and strife. Penance fixes that. We must go without the goods we love in a disordered way to target the source of our sickness.

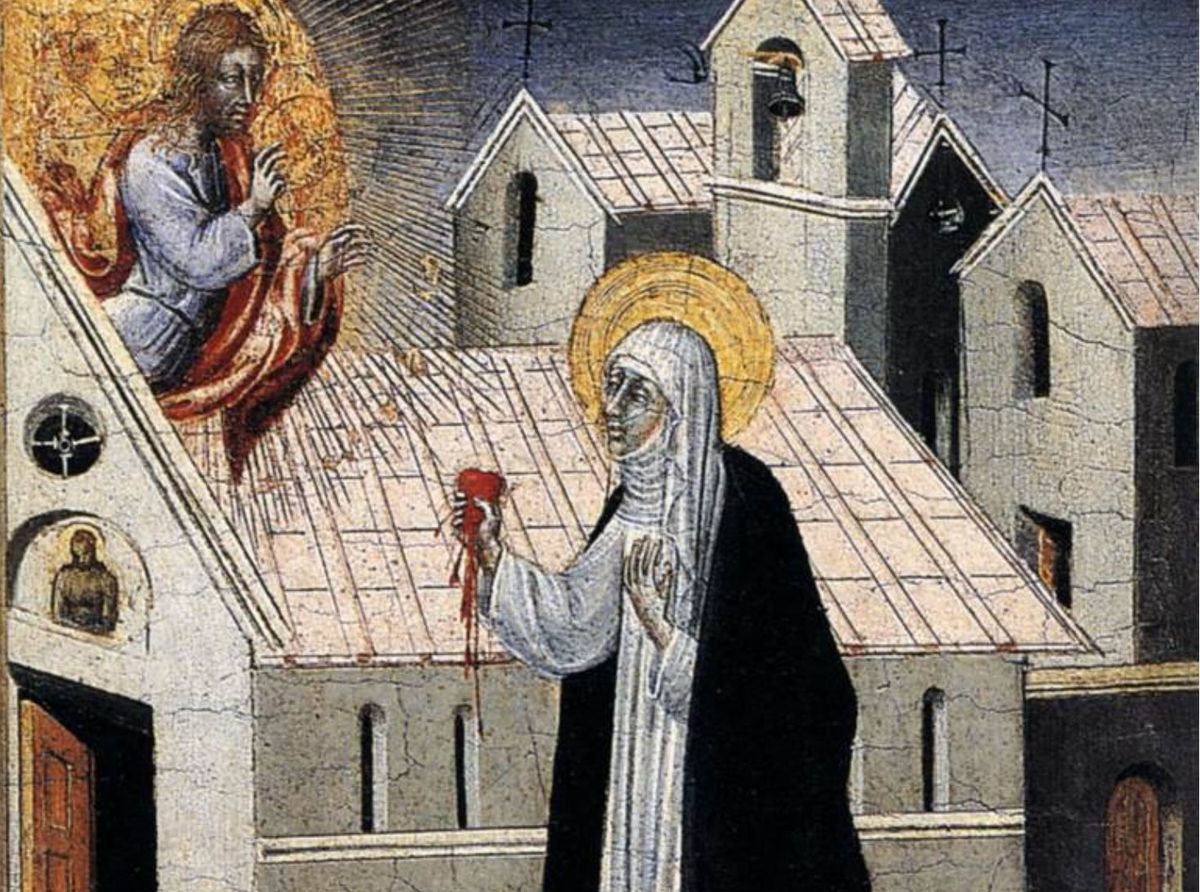

But do not get the wrong picture. Penance is not primarily about loving and enjoying the goods of this world rightly, even ourselves, or our neighbors. It is first about preparing for the heavenly feast. It is first about loving God properly. The key to recognizing how penance prepares us to feast is that in feasting we celebrate and rejoice in something good. We need penance to do this correctly with all the finite goods of this world, but we need it more to remember and rejoice in the infinite good, God himself. Penance keeps love open to the surprises a relationship with God brings. For example, at Easter or in the Eucharist we receive a gift which is beyond all the goods of this world. Giving up the limited goods of this world both offers a fitting reparation for our sins and helps us keep our love focused on God himself. This is the logic of creation, to recognize the transcendent source of all goodness, but also to recognize that the things of this world are not God and will not fulfill us. Will we recognize him when he comes if we are overly attached to this world? Will we even want the offer of eternal life if we are seemingly satiated by finite goodness? Will we miss the gift of the higher good and settle for the lower? Not if we are people of penance; not if we train our love. We need weekly and seasonal formation and the myriad of penitential seasons serve this purpose. This is the deep wisdom of putting a penitential season before a feast. God is coming; prepare yourself to meet infinite goodness. Can we feast unless we fast? It seems not.

In short, penance both prepares us for the heavenly feast and for the feast of this world, to rejoice in God and in the goods God has created. Put differently, the three purposes of penance, to make reparation for sin, to prepare for the kingdom, and to love this world rightly, are one and the same. A distorted love of the goodness of this world not only damages our seeking of God, but also our very possession of the things of this world. Put more precisely, a distorted love of God prevents us from our enjoyment of the things of this world. Far from removing us from this world and denying it, penance is a radical affirmation of the (limited) goodness of this world. Things are created by God and ordered to him, if we do not seek them this way, then we do not love them as they really are. When the things of this world are not ordered to God, they cease to be good in some fundamental sense. We become like fanatical football fans for whom the victory of their team is the final good and the organizing principle of their lives. Is football sought that way good? No. Is it good sought in a limited sense for leisure or recreation? Certainly. Is it fitting that we give up this good for a time in reparation and a retraining in our loves? Absolutely. The same is true of all the things of this world, and each of us can think of the worldly good which most tempts us. The good things of this world lose their goodness apart from God and our disordered pursuit of them is a sign that we do not love God fully. Yet, with this love, we get the world too. With God we get the world. Without God, we lose even that which we sought in the world.

We see the potency of the Church’s wisdom in the joy and gratitude it brings. When we love the goods of this world as ordered to God and as gifts from God, a true joy erupts (a real feast). Everything is a gift. It is by seeing the world this way and clinging to a love of God above, before, and beyond all things that we can truly rejoice in this world. “Only solitary men know the full joys of friendship.”

Put in a different context, only those who have slept on the floor can love the good of a bed. Try sleeping on the floor for 40 days, and you will see how good a bed is and rejoice in it, but you will also be ready to give it up if Love beckons. It is only by divesting ourselves of possessiveness that we truly possess: ourselves, each other, the goods of this world, and ultimately God.