I have been asked to offer some reflections on the lessons I have learned from my lifelong experience in Interreligious Dialogue for Peace. I want to stress that for me, interreligious dialogue is not for its own sake but in view of peaceful living together among persons from different religious persuasions. First let me give a brief outline of my interreligious life journey.

Personal Backround

From my childhood, I have been bred and raised in an atmosphere of interreligious living together. Although I was born into a very strong Catholic family, we lived at peace with people of other faiths.

Early Childhood.

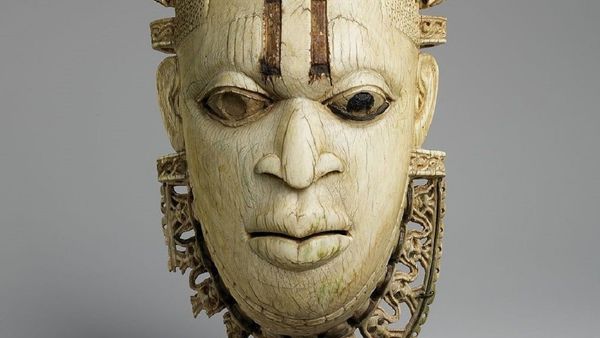

First of all, let me start from the beginning, from when I was born on 29 January 1944. According to the custom of our people, my father gave me a name, which expresses his mood at the gift of a baby son. He gave me the name Olorunfemi, which means “Olorun loves me.” This name, which is common among my people, goes deep into the religious traditions of our people. Olorun is the Yoruba name for God, the Supreme Being, the Almighty Creator, whose worship is the foundation of our traditional religion. I was taken to Church the next day and baptized with the name John. I know that he had in mind John the Baptist, since his two previous children were baptized Joseph and Mary, and my next sibling, a girl, was naturally Elizabeth. I myself later decided on John the Evangelist, the Beloved Apostle, as my patron saint.

But before John, there was Olorunfemi, confirming the deep faith of my father in Olorun, the same God who is the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. This attachment to the “God of our Ancestors”, has remained with me all through life. That is how my father put me on my inter-faith life journey.

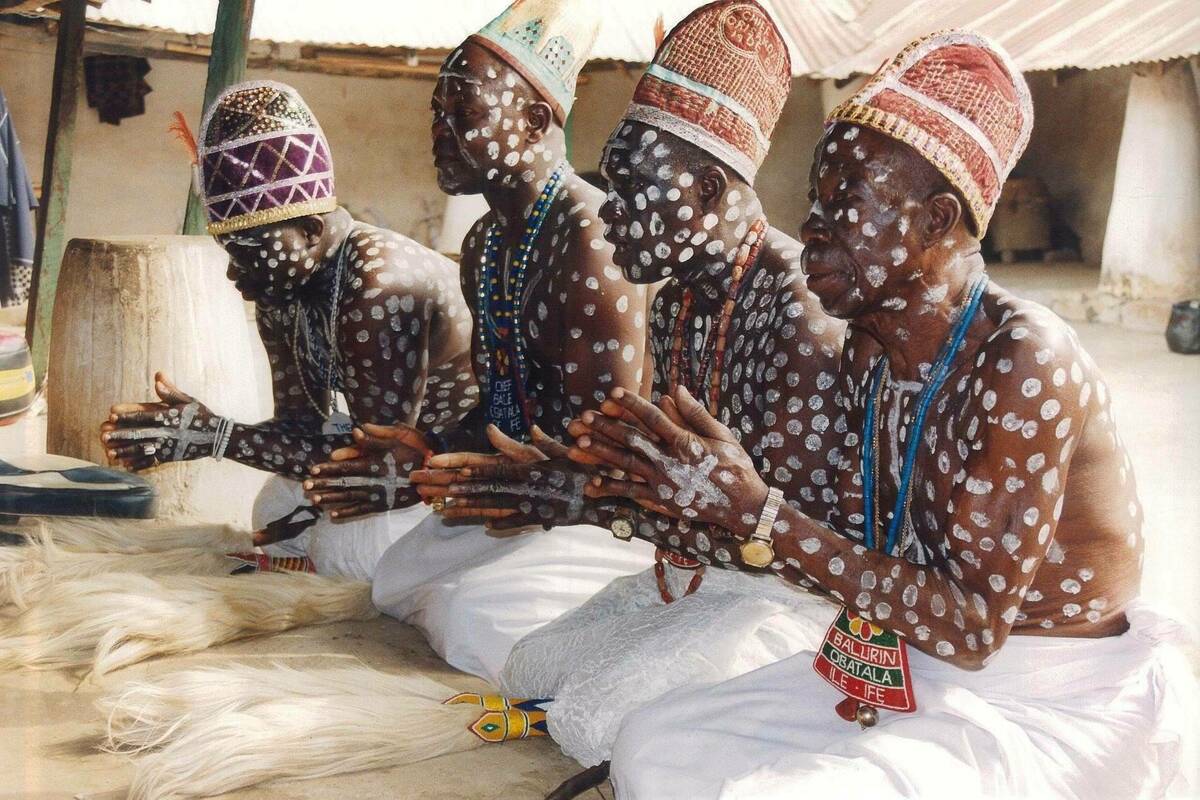

At the time I was growing up, the African Traditional Religion was still very active in our little community of Kabba. Many members of my family remained attached to our traditional religion. I still remember very well the senior brother to my father, my uncle, who was the head of the traditional religious cult in our little village of Anyongon. He used to visit my father in the bigger town of Kabba every now and again. When he died, his body was brought from Anyongon to Kabba by my father, and given full burial, in line with the traditional religion of our people, as a chief with the dignity of a chief. This was notwithstanding the fact that my father was the head of the Catholics in town. He did not shrink from his duty to facilitate the proper traditional burial of his brother. As a young boy of about 5 years, this made a deep impact on me.

There were other members of my family, both from my father’s and my mother’s side who remained staunch practitioners of our traditional religion. Another example was the senior cousin to my father, Chief Obatimeyin, who led the traditional worshippers in a section of Kabba called Odolu. He was present at my priestly ordination in rapt attention, at the end of which he congratulated me saying, “Yes, you have done well. In our family, this is how we are. Whatever we do, we do it well. Batholomew (namely my father) has done very well.”

On my mother's side, my mother's father was one of the leaders of the traditional worship in the palace area of Kabba. When he died, my mother got caught up in the rituals for his burial to an extent that my father was very angry that they should be involving my mother in their mysterious and mystical practices. But he respected them. Thus, I was taught from the very beginning never to look down on the religion of our ancestors, even though my father constantly warned us not to dabble in their celebrations. That is practical dialogue with the African Traditional Religion on a very personal level.

As for ecumenism, the Christian faith first came to our community of Kabba, first with the preaching of a charismatic preacher called Joseph Babalola. He preached in our town in a very successful crusade. All he demanded was that people should abandon the traditional religion, believe in Jesus Christ, and become Christians. But he did not have any church of his own. Rather, he asked people to go and join any Christian church of their choice. My father decided to join the Catholic Church. Some of his friends and even members of our family joined the Anglican Church, which was the only other Christian denomination in the town at that time. Furthermore, my mother's junior brother decided to become a member of the Christ Apostolic Church, an African charismatic denomination, which was later brought to the town.

What all this meant was that I grew up with my uncles and aunties and their own children who are my cousins, all of us in different Christian denominations and we did not find anything strange about it. We took it in our stride, even though at this time, the ecumenical idea was definitely not yet in vogue in our church. The Irish Catholic missionary did all he could to let us know that it is only the Catholic Church that is the true Church of Christ. All the rest, we were told, were man-made. Protestants are the people who have created for themselves their own fake Christianity. We called them in Yoruba “Aladamo,” meaning those who have created their own doctrines. But despite all this, it did not stop us from having a good relationship with our cousins and uncles who did not follow the Catholic line.

Furthermore, at that time as a child, I still remember one of my uncles who somehow against all odds had become a Muslim. The Islamic faith did not take root in our community. He was one of the few in our community who called himself a Muslim, with the name Suleiman. But he was still a very likable fellow. He visited my father regularly and we children had great respect for him, even though he was a Muslim. Therefore, already at the age of 5,6,7 I had an uncle who was a Muslim, and I did not see him as being somebody who should not be respected for his faith. Thus I grew up from early childhood in a society where the African Traditional Religion, different denominations of the Christian faith and even the Islamic religion were at home.

School Life Experience

Later on, I went to a Catholic secondary school where the entire environment was specifically Catholic. It was run by Holy Ghost missionaries for whom the school apostolate was a major form of evangelization. Even though the entire school's daily program was clearly Catholic, with holy mass every morning and other prayers every evening, yet the school was open to children who belonged to other faiths. I still remember very well the very few Muslim students who studied with us. They were expected, and they did comply, to attend Mass every morning, even if they went there to sleep or to read other things. But they were there with us. However, they were not forced to be Christians. In fact, for the Muslims, during Ramadan, provisions were made for them to be able to fast.

I still remember very well my friend, Sabo who had a tenacious compliance with Islamic injunctions, especially during Ramadan. This filled me with great admiration. Here is a young boy who, after just an early heavy breakfast, would neither eat nor drink until sunset. And yet he joined in every aspect of school life, including games and manual labor. I constantly admired him for being so consistent with his faith.

Sabo Ago took it upon himself to slaughter the goats and rams that used to be provided for our meals in the kitchen. He had to do this so that he would not have to eat meat that had not been properly slaughtered. If by any reason he was not available when the cooks needed to slaughter the animals and someone else did, it meant that my friend Sabo Ago would not eat from the common pot on that day because the meat had not been properly slaughtered. Again, this filled me with great admiration for him because it meant he would just make do with whatever he could find to fill his stomach, provided he did not participate in meat that had not been properly slaughtered. That gave me occasion to also have some kind of idea about the beliefs and the practices of the Islamic faith, even though it was from a few young boys in the same school.

My Journey in Priestly Formation

My life journey in priestly formation started in 1963 in the major seminary in Ibadan, Nigeria. The theological climate at the time was clearly pre-Vatican II, But the Vatican Council already started in 1963. I was in Ibadan until 1965, and already, echoes of the Vatican Council had begun to trickle in to the curriculum of the seminary formation. However, what reached us most immediately were the liturgical changes that had started, especially as regards sacred Mass in the vernacular and the gradual introduction of African music not only in terms of tones and rhythms but also instruments of music like drums and gongs. This was the first aspect of the Vatican Council that we saw. We had not yet begun to see all that Vatican II brought in as regards interreligious understanding.

However, by summer of 1965, I was sent to Rome to continue my priestly formation at the Collegio Urbano de Propaganda Fide. We landed in Propaganda Fide, with many other young seminarians from all over the mission lands in September of 1965. The Vatican Council ended in December 1965. The documents of the council were promulgated and they were all bestsellers. I therefore started my theology with a lot of reports in the theology class about what had happened in the Vatican Council. Most of our major professors especially of dogma, canon law, and liturgy had been periti or experts in the Vatican Council. And so, I had four years of theological formation in Propaganda Fide, in the immediate aftermath of the Vatican II.

On the one hand, by its very name, Propaganda Fide was an institution to train young candidates from the mission lands to be missionaries back home when they return. We were supposed to get ourselves ready to spread the Catholic faith and to be faithful to the Catholic faith even unto the shedding of our blood. As far as the importance of the Catholic faith is concerned, the formation of the students in Propaganda Fide was precisely to make us zealous preachers of the Gospel.

However, at the same time, the Vatican II had come out with documents like Lumen Gentium, on the Church, Unitatis Redintegratio about ecumenism and. above all, Nostra Aetate about non-Christian religions. The theological atmosphere was full of debates about how far we were going with regard to ecumenism with fellow Christians who are not Catholics and also opening up to other believers who are not Christians, as we see clearly in the two major documents Lumen Gentium and Nostra Aetate.

The result was that, my formation as a theology seminarian in Rome was quite balanced in terms of being, on the one hand, anxious to go and preach the Gospel to the ends of the earth, but, at the same time, I was made to recognize that other Christians were also Christians and that other believers in God deserved my respect. It was with this mood that I came back home in August 1969 for priestly ordination.

I spent two years at home teaching first in a secondary school and later in the junior seminary. I was eventually sent back to Rome for further studies, first at the Biblical Institute, and later at the Urbaniana University, for a Doctorate in biblical theology. My doctoral thesis was a comparative study of the concept of priesthood in ancient Israel, and in the traditional religion of my people. It is obvious here therefore that I already had a strong interest in interreligious study of the community in which I was to find myself. I therefore came back home with a doctoral degree with emphasis on interreligious dialogue, especially with African Traditional Religion, as well as of a licentiate in Sacred Scripture, which I had begun to learn to read with an open mind.

Life as a Priest in Nigeria

After a year teaching in the junior Seminary in my diocese of Lokoja, I was posted to the major seminary in Ibadan to teach scripture as well as act as rector of the seminary. There was also ample opportunity for pastoral work with the local community of Catholics who lived around the Seminary or who patronized the Seminary for their regular Sunday Mass.

My time in the Major Seminary allowed me to put into practice much of what I had learned about ecumenical and interreligious dialogue, especially on the academic level. I was quite involved in discussions with theologians of other Christian denominations especially in the Protestant seminary, the Emmanuel College, which was in the same area as our own major seminary. There was also at that time an association called the Nigerian Association for the Study of Religions, (NASR) where teachers in universities and Seminaries as well as the Islamic Institutions met for annual conferences where we discussed Christianity, Islam, and African Traditional Religion as these relate to the various issues of our nation. That experience opened me up to not only Protestants theologians but also Muslim scholars who also were grappling with the same issues that we were dealing with. We were all seeking ways to bring to bear our theological doctrines with the realities of our society and of our nation. It was an exciting experience.

Life as a Bishop

I was appointed a Bishop in July 1982, and ordained in Rome at the St. Peter’s Basilica by Pope St. John Paul II in January 1983. My first appointment was as an Auxiliary in the Diocese of Ilorin, a city tat was particularly important for interfaith and ecumenical relations.

First, in the area of interfaith relations, Ilorin is a strongly Muslim town and the relationship between Christians and Muslims in that town had always been very problematic. The slightest discussion often became violent, especially among the young people of both religions. My six years in Ilorin gave me ample opportunity to step in and try to find ways of getting Christians and Muslims to listen to each other and working towards a non-conflictual relationship. Incidentally, to do this, I needed to pay attention to the ecumenical dimension of our relationship with our Muslim neighbors. That meant therefore that I needed to encourage pastors and leaders of other Christian denominations to meet regularly to try and understand better one another, so that we can have a common and coherent mind when we face Muslims in dialogue. Thus, Ilorin gave me the opportunity for an experience with the Christian Association of Nigeria, of which I was soon elected for some time as the chairman. It was also an opportunity for closer relationship with the Islamic community.

In 1990, I was moved to the Federal Capital of Nigeria, Abuja. There, I was launched into the national level of the relationship between Christians among themselves and between Christians and Muslims. It was from Abuja that I became an important member of the Christian Association of Nigeria. For some time I was President of the Christian Association of Nigeria at the National level. That also brought me in touch with the Islamic leadership of Nigeria under the umbrella of the Nigerian Interreligious Council. It was in this instance that I developed very strong personal relationship with some Muslim leaders, especially with the head of Muslims, the Sultan of Sokoto Sa’ad Abubakar. It was because of this that I was involved in efforts to bring Christians and Muslims groups together within the city of Abuja. Along with the Executive Director of the National Mosque Alhaji Jega, we formed an Inter faith dialogue group for Abuja, which moved on very simple and modest level but opened up the whole idea of Christian and Muslim leaders talking together. There were plenty of things to talk about, because there were various issues that kept arising making the relationship difficult.

On the national level especially during a period when the Nigerian Inter-Religious Council went into a kind of coma, I co-founded an NGO called Inter Faith Initiative For Peace, with the Sultan Abubakar Sa’ad. The initiative still exists.

Finally, towards the end of my tenure as Archbishop of Abuja, I founded an NGO, which went by the name Cardinal Onaiyekan Foundation for Peace. The unit is part and parcel of the interreligious activities of the Archdiocese of Abuja, but for the moment under my chairmanship. The COFP has been very active bringing middle-level religious leaders together on various issues and especially training them in interfaith living together at the grassroot level all across the country. It organizes an annual fellowship program for interfaith peacebuilders, which has extended its influence beyond Nigeria, and admitting candidates from other African countries. The last session had about fifty candidates, including ten from outside Nigeria. This is my life journey and from this life journey, I have learned a lot of lessons.

LESSONS LEARNED

The Reality of the Religious Pluralism

I have the conviction that religious pluralism is a fact that we can no longer deny whether we like it or not. Not only Nigerians but men and women all over the world have made religious choices as regards how they will worship God and in the different religious organizations that we see around us. There are some that are well-known. Obviously, we talk especially about Christianity and about Islam, the two religions that most affect us in Nigeria and in Africa. But if we go global, we must then think of Hinduism and Buddhism, which also cannot be overlooked.

But the more significant fact is that we need to go beyond simply acknowledging the pluralism of religion. We must go beyond tolerance, and go into respecting the pluralism of religion. It is not always easy for people who are convinced about the truth of their religion to at the same time accept that the pluralism of religion may well be a God-given reality. I have come to the conclusion that pluralism of religion is all within the plan of the Almighty God who is greater than any religion.

Mission and Dialogue Are Compatible

In the past, the missionary was thought to be someone who would do everything to make everybody follow his religion. As Catholics and Christians, we have long interpreted the mandate of Jesus: “Go to the whole world and preach the Gospel to all nations” to mean that we must aim at making everybody Christian, in such a way that we find it difficult to have anything positive to say to, or, to have any positive discussion with, anybody who is not ready to be converted.

Unfortunately, this kind of attitude is also what we find among fanatical Muslims who themselves have the idea that the whole world must be converted to Islam. These two religions particularly have a great responsibility in this regard. They have to find a way of holding on to their universal mandate and at the same time recognizing the right of others to have a similar intention. For as long as they do not make room for others, then there will be no room for dialogue. Dialogue must mean that we acknowledge that the other has something valid to say.

Cardinal Arinze used to say that “dialogue means I talk you listen; you talk I listen.” I will listen only if I believe that you really have something worthwhile to tell me. We have to go beyond politely listening to each other and sincerely listening to what the other needs to say. Dialogue does not negate, nor is incompatible, with our mission mandate. We can continue with our mission mandate and at the same time make room to listen to others. In the process, the differences between us are easily explained and understood and, as we shall see later, we will be able to discover the many common grounds that we have.

The Church has a beautiful document on “Proclamation and Dialogue” which deals with this matter. It was a document jointly published by the then Congregation for Interreligious Dialogue and the Congregation for Evangelization of Peoples. These two congregations jointly came out with this document to, on the one hand, affirm the need and the importance of mission and proclamation and at the same time, the necessity of engaging in dialogue.

Seeking Common Grounds

Religious pluralism naturally stresses the fact that we have different religions. Unfortunately, we emphasize our differences to the extent that we tend to identify ourselves on the basis of these differences. “I am a Christian because I am not a Muslim,” and vice versa. But in that way, we tend to identify ourselves not by what we are but by what we are not, by how we differ from everyone else!

Therefore, there is a need to make the effort to seek, discover, and celebrate the common grounds that we have among our different religions. If we do not dispose our mind to this, we will only be seeing the differences and will never see where we have common grounds.

Our common grounds are many. There are doctrinal common grounds. One of the most common elements of this common ground is the very belief in the one God. We must insist that the Almighty God has made himself known to the whole of humanity. St Paul says as much in the Epistle to the Romans. The first item in our Christian Creed is “I believe in one God.” If we cannot believe that others have the same God, then it becomes doubtful whether we really believe in one God. If you believe in one God, there cannot be another God for Muslims, another God for Buddhists, and another one for Hindus.

Even where we have major doctrinal differences, there are still some common elements. Let us take for example, the person of Christ, which is the very great distinguishing item of our faith that distinguishes us from every other religion, especially from Islam. When we look more carefully, especially with Muslims, we see that we share a lot of things in terms of who Jesus is. Obviously, the Islamic idea of Jesus is not the same as the Christian idea of Jesus. But it is not an insignificant matter that the Muslim has great regard for Jesus as a great prophet and respects his mother Mary as a Virgin Mother. We need to gladly celebrate these facts before we begin to quarrel over the things that we cannot reconcile.

Similarly, we have many common moral values. There may be differences in details as regards moral norms and behavior. But as far as basic moral values are concerned, values like honesty, sincerity, and solidarity. We have a lot in common. We need to acknowledge this so that we can work on them in terms of cooperation in practical life.

Similarly, in the general area of worship, if we are ready to respect the way others approach God in prayer, we will discover that we have really a lot in common. An example is the fact that we believe in God who listens to our prayers. There are observances and ways and means of showing our respect for God. There is a belief in sacrifice and fasting. These are aspects of religious worship that we generally hold in common but which we do not often acknowledge. And so, when we seek common grounds, we discover them and we should celebrate them for what they are.

There is also a common ground in terms of the challenges that face us. Nigeria is a good case in point. Whether you are Christian or Muslim, most of our challenges are the same. There are the same problems of conflicts, bad governance, the terrible plague of corruption, the natural problems of disease, and a lack of good health facilities. In these matters, it is not a matter of being Christian or Muslim. It is purely a matter of human needs, and the more we pay attention to this, the more we can understand each other and live and work together. We have common challenges, which are also our common grounds.

Religion and Peace

Every religion talks about peace. Christianity believes in Jesus, the Prince of Peace. Islam says that the very word “Islam” means Peace. Therefore, one would expect that religion should bring peace. The ideal still remains that religion is for peace.

However, unfortunately, the reality is that very often, religion has been used for war. Or, shall we say, religion has often been misused and manipulated for war. In our Nigerian context, religion has been very badly manipulated for politics. Our religious differences are being exploited for the selfish interests of people for whom religion is not really a major concern.

This being so, religious leaders have a duty to liberate themselves from these influences that are making it difficult for religion to be itself and to play its proper role in peace. That is why it is important that we emphasize the necessity of interreligious conversation, especially among religious leaders but also among religious communities.

We must also not forget the importance of intra-religious dialogue. Religions like Christianity and Islam have divisions within themselves, which sometimes have caused conflicts that are as virulent as conflict with other religious bodies. The history of Catholic-Protestant wars in early modernity is a terrible lesson for us to keep in mind. Also, within Islam, there has been a long history of conflict, especially between Sunni and Shiite, which is still visible today. Therefore, religions must make peace with themselves. It is only then that religion can be effective in bringing peace to humanity. When religious leaders have a joint position and they come together to mediate, they do so with great efficiency and power. This is especially so where religion is part of the issues that are causing the conflict. Religious leaders must be bold to link hands and get involved in peace building and conflict resolution even when they are not invited. Religion is for peace, and should always be for peace.

Religious Freedom as a Fundamental Human Right

To respect the fundamental human right of religious freedom, we must accept the basic equality of every religion, even when it is a small minority. This is not an area where the majority carries the day. Everybody must be allowed to follow God according to his or her conscience.

At the same time, however, there may be a limit to how much one can express one’s religion. This is because your freedom to express your religion must respect the freedom of others. As we usually say, “Your freedom stops where my own begins.” This is often a problem that is not impossible to resolve but which we must recognize.

As far as religious freedom is concerned, there is always the matter of the state. If the state does not uphold the rights of religious freedom, it is difficult for weak minority groups to stand up on their own. The state must therefore be impartial in this matter even when a particular religion may have greater political and economic clout. The state must defend the religious freedom of everyone, irrespective of whether one is in the minority or majority.

Recently, my friend Bryan Grimm has done a lot of work and a lot of moving around the globe espousing the great idea that religious freedom is good for business. He seems to have achieved a great amount of success in convincing both religious leaders as well as business executives that both religion and business have everything to gain by giving room for religious freedom. His project seems to be worth paying very close attention to.

Religion in our Contemporary Globalized World

We should remember once again, in our global world people are moving from one part of the world to the other. With ever-improving means of transportation and the revolution in communications technology, it means that we hear and see one another across the whole planet. Therefore, it is no longer possible for any religion to stand aloof or to isolate itself from others. The very fact of globalization means that we must take religious pluralism very seriously.

It is providential and we should thank God that there are many interreligious institutions now in the world. The most well-known to me is the Religious for Peace International, based in New York, which brings together the leadership of most of the major religions in the world, organized according to regions, and National Interreligious Councils. But it is not the only one. There is a group called The Parliament of World Religions and there are other people who are involved in this idea of bringing religious leaders together so that we can build a better world under God.

We cannot forget the great importance of some recent gestures made at a global level. I am thinking especially about the meeting between Pope Francis and the Grand Imman of Al-Azhar Mosque, Sheik Al-Tayeb. The two great religious leaders came out with a powerful common document, with the significant title, “On Human Fraternity.” In the document, they both formally declare that all of us, not just Christians and Muslims, the entire humanity are brothers and sisters. This will make sense only if we admit that there is one Father, whom we call called God by different names.

This document of the pope and the sheik has been endorsed and accepted by many other religious bodies worldwide, both Christian and Muslim groups, as well as other world religions like Buddhism, Hinduism, etc. For me, this is a special grace that God is giving to our world and we pray that we can pay necessary attention to it.

Finally, I want to mention the gradually growing place of religion now in the United Nations and its agencies. For a long time, these bodies have shown some kind of allergy to dealing with religious institutions, either because they believe that religion is bad for society, or because they simply did not find a language to speak with religious organizations.

The allergy perhaps is mutual because the religious body did not show much interest in the UN. In this matter, the Catholic Church from the beginning has been an exception. That is the origin of the Permanent Observers and Representatives of the Holy See in the United Nations and in its agencies. Other religious bodies have now established such contacts with the United Nations. What is more interesting is that recently, the United Nations itself has decided to establish a framework for religions to relate easily with its work. How far this will go, we do not yet know.

Conclusion

And with this, I can say I have come to the end of the lessons that I have learned from my long journey of Inter-Religious Dialogue for Peace. The journey is not over yet but I hope it will not be too long since I turn 80 already in January 2024. May the God of Peace grant us harmony in our world, globally and locally. Amen.

EDITORIAL NOTE: A version of this essay was delivered on 29 September 2023 at the World Religions World Church Colloquium with the title, "Lessons from a Life of Interreligious Dialogue for Peace in the World."