There was a scholar of the law who stood up to test him and said, “Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” Jesus said to him, “What is written in the law? How do you read it?” He said in reply, “You shall love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, with all your being, with all your strength, and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.” He replied to him, “You have answered correctly; do this and you will live.” But because he wished to justify himself, he said to Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” —Luke 10: 25-29

“And who is my neighbor?” Referring to the neighbor of the greatest commandment, this question could be more openly expressed as follows: “And who is the person I am to love as myself?” Digging into the challenge’s implications, we can hear the scholar converging, indignantly, on questions of worth: “Who is my equal, whose good obligates my self-forgetful response? Who is worthy of my own self-giving, my own life?” Still further, burrowing to its roots in the Latin dignitas, or dignus, this notion of “worthiness” stems from and thus reaches its deepest implication in the essential matter of dignity. “Whose worth, or dignity, is equal to my own and so merits my love?”

The scholar’s essential question resounds today, as we continue seeking to define, not only who is my neighbor, but also what exactly constitutes her worth or dignity. What is human dignity? What are its defining characteristics, its parameters, and its implications? Popes and secular leaders alike invoke the concept of human dignity as the foundation and spark for loving one’s neighbor.

Yet, when pressed, we struggle to articulate this concept’s precise meaning. “Human dignity” threatens to be a buzzword, a vaporous concept invented by humans to serve their anthropological need. Our inability to define it causes us to wonder if our most concrete expressions of charity toward neighbor—such as in human development and social justice work —are, ironically, founded upon an insubstantial “concept,” a diffuse foundation. How valid, how real is “human dignity”?

Returning to the scriptural question, “Who is my neighbor?,” the quest to comprehend the worth or dignity of our neighbor may expose a deeper insecurity in the very command to self-donation for this person’s sake. Like the scholar, we are provoked by a felt need for reassurance that the extension of self—that is, love —for the sake of the supposedly “worthy” or dignified person is truly worthwhile.

And so, at its core, our desire to comprehend may arise not so much from our suspicion regarding the validity of human dignity as from a doubt in the substantiality of love. We fear being made fools should we give ourselves over to the dignity of another, only to discover that self-donation leads to loss rather than the inheritance of life’s fulfillment (Mt 10:39; Lk 10:25). Thus, as a safety measure, we attempt to delimit both the identity of our neighbor, the one equal to us in dignity, and the extent to which we must love her.

“Perfect love drives out fear. . .. We love because he first loved us” (1 Jn 4:18-19). Christ responds with a love that drives out our fears. As we hear in his reply to the scholar, He does not stoop so low as to indulge the human expectation. Rather, he stoops even lower, disclosing the truth that, while intelligible to our human reason, is revelatory in its humility and generosity. Because Christ, the Word, speaks words of divine revelation, he offers not so much definitive explanations of one’s neighbor and of her dignity as contours for our contemplation of those realities.

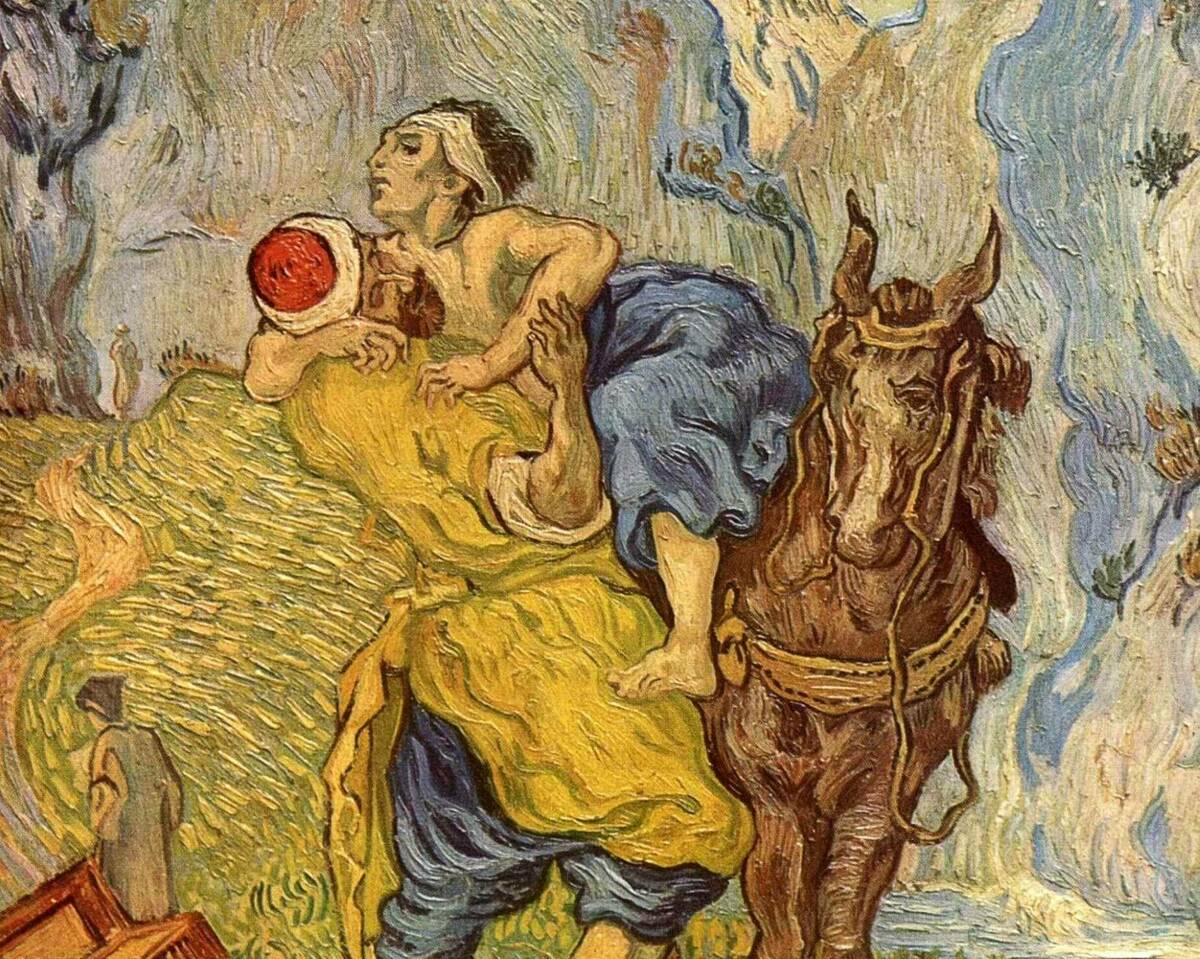

This he does through the parable of the Good Samaritan, wherein the neighbor is a comprehensive figure; the dignified neighbor constitutes not only one’s apparent equal but also, and even especially, the most other Other, the person whose worth demands the furthest extension of love, to the point of a self-forgetfulness that prefers their good over and above one’s own. Blessings abounding, this extensive reality received from Christ’s mouth is also generative. In the living recognition of another as neighbor, the two become mutually defined in their relationship as neighbors. For, the neighbor is not one character in the story.

On the contrary, “neighbor” is both the “robbers’ victim” and the Good Samaritan, both the needy one and the “one who [treats] him with mercy” (Lk 10: 37). As he recognizes the victim as his neighbor, hears his dignity crying from the ground, the Samaritan effectively humbles himself to the identity of neighbor (Evangelium Vitae §7-17; Gen 4:10). By his very gesture of mercy, he confesses shared dignity with the wounded, helpless man. This newfound solidarity begets a union of wills; the Samaritan not only prefers the victim’s good above his own, but the victim’s good actually becomes the Samaritan’s own good, and the two become bound together in a reciprocal relationship of love. They live into who the grand, though heretofore hidden, reality of their correlative identities, making visibly manifest the form which already, most truly is.

This enlightened identification of one’s neighbor revolutionizes, too, the concept of love. The scholar in Luke’s Gospel sees love as a means to eternal life, and so he implicitly begs Christ to state the bare minimum of loving required in order to escape death. But Christ’s revelation of the dignified neighbor in the parabolic figures supplants such minimalistic thinking with divine and personal resonance. The Samaritan’s most concrete and gratuitous care for the victim ultimately shines forth a vision of a love so great that it is recognizable, not as the mere means to but rather the very content of life. Indeed, the perfection of this love constitutes life eternal, which is unbounded and perpetual, Self-outpouring Love; it is the divine life and Name of our Triune God himself.

Of course, the parable cannot portray this reality in its fullness. Rather, it gives way to its perfect Image, Christ’s embodied self-gift to us on the Cross (EV §25). In Christ Crucified, we receive the most extensive and generative love and life, issuing forth from the side of the most other Other—God! Mercifully, “though [Christ] was in the form of God, [he] did not regard equality with God something to be grasped . . . Rather, he humbled himself,” taking the form of our neighbor. Claiming this identity in relation to us, he thereby confers on us a new dignity as his neighbors (Phil 2:6-8). Though he had no need of us, he deemed us worth the sacrifice of his own life; looking upon us, he loves us (Mk 10:21).

As revealed on the Cross, the Gospel themes implicit in the question “who is my neighbor?” —those of love, dignity, and eternal life—are not discrete realities. Rather, in Jesus Christ, we see they are intermingled: “The Gospel of God's love for man, the Gospel of the dignity of the person and the Gospel of life are a single and indivisible Gospel” (EV §2). Therefore, though “human dignity” is partially accessible to unaided human reason, it is primarily and ultimately bound up in God’s love and life (EV §2; Gaudium et Spes §22; see also: Cavadini). “The root reason for human dignity lies in man's call to communion with God,” beginning with our “creation in the image and likeness of God” and finding its perfect fulfillment in our “vocation to divine beatitude” (CCC §1700; GS §19).

Borne from divine love, we are destined to the integral beauty of eternal life, wherein we become one with that primal communion of love. We see, then, that “human dignity” is by and large a theological truth, whose “coordinates” lie in the hypostasis of our being and God, our poverty and his abundance of life and love. Most credibly witnessed by the Incarnate Word, human dignity is not a fluffy conception but rather a most real and substantial reality, as concrete as the Samaritan’s gestures of bandaging, carrying, and housing his wounded neighbor. As concrete as Christ’s body and blood (EV §§7-17, 25). We struggle to grasp “human dignity,” not because it is too small or esoteric, but because it transcends our ability for grasping and instead invites our intimate and active, or living, contemplation of it. It is a reality to which we may faithfully give ourselves so as to come to know its essential form. Little by little, we might con-form to the reality of human dignity by our lives, and like the Good Samaritan, become revelations of God’s dignifying love for us.

Living Contemplation of Human Dignity: Balthasar’s Theological Aesthetic

Jesus Christ himself . . . is “the way, and the truth, and the life.” It is by looking to him in faith that Christ's faithful can hope that he himself fulfills his promises in them, and that, by loving him with the same love with which he has loved them, they may perform works in keeping with their dignity . . . For to me, to live is Christ. (CCC §1698)

Having established human dignity as primarily and ultimately revealed, and not in definitive terms but by the very Person of Christ, I wish to propose dislocating the discourse of human dignity from our scholarly urge to know and instead commit to a living contemplation of Christ’s charity (caritas). This charity “is a force that has its origin in God, Eternal Love and Absolute Truth,” and so it is always linked to and revelatory of the Truth: “In Christ, charity in truth becomes the Face of his Person, a vocation for us to love our brothers and sisters in the truth of his plan. Indeed, he himself is the Truth” (Caritas in Veritate §1; Jn 14:6). Insofar as it is a revealed truth originating in the Absolute Truth of God, the revelation of human dignity is wrapped up in this charitable Self-revelation of Christ; we encounter human dignity-in-charity-in-truth.

This encounter is necessarily personal, or better yet, interpersonal. What is more, it is categorically beautiful, given Christ’s incredible humility in making himself, the fullness of Divine Being, sensible to us in such an intimate and full manner. The beauty of this encounter with Christ, Who is caritas, dazzles and delights, calling us beyond ourselves to “love our brothers and sisters in the truth of his plan.” It invites us into a self-forgetful participation in his charity, “performing works” by our lives to make known the Father’s eternally dignifying love for humankind.

This living contemplation thus entails our participation in the revelation of Christ’s charity, understood as his total self-disclosure to humankind, body and soul. We will now turn to theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Love Alone is Credible to further ground and develop this mystagogical contemplation of human dignity in terms of theological aesthetics. Aesthesis means perception. His theological aesthetics refers to the revelation of God’s truth made beautifully and beatifically perceptible through matter. This revelation involves us, enabling us not only to perceive but ultimately to participate in the truth revealed.

As Balthasar elucidates, the participatory level at which “the creature gives himself over into this drama, into this revelation,” describes a dramatic aesthetics.[1] One enters into the drama of salvation. Conforming our lives to the gift of charity-in-truth, we make that gift perceptibly, and really, present. And so, as we perform his charity, the essential truth of the dignity he has claimed for us is made manifest. But before our contemplation of Christ’s praxis can “blossom as a response within us,” we must first “see and experience his love” (Deus Caritas Est §17). Perception must precede dramatic participation.

As we see in the parable of the Good Samaritan, the perception of God’s self-disclosure of charity is not a given, but a gift. Out of the three passersby, the Samaritan is the only one to recognize in the robbed man the image and likeness of love: the same love by which both men were created and to which they are together destined, the source and summit of their dignity. It is because the Good Samaritan recognizes and encounters this love that he responds accordingly.[2] He responds in the love which he first received (1 Jn 4:10). Thus, to perceive the revelation of charity is to receive it.

To truly receive the charity of Christ is, furthermore, to offer it back in gratitude.[3] For the truth of Christian charity is revealed in His neighborly act of “emptying himself, taking the form” of our neighbor; it is, essentially, kenosis, the dynamic gift of eternally self-emptying love (Phil 2:7). Lest the gift cease being a gift, it must continue to be given. And so the neighbor participates in this kenotic act which he first received, offering all his faculties in the name and, indeed, in the Body of Christ (CCC §1698). In Deus Caritas Est, Pope Benedict XVI concretizes this participation as the Eucharistic act of Thanksgiving (Eucharistia): “The Eucharist draws us into Jesus' act of self-oblation. More than just statically receiving the incarnate Logos, we enter into the very dynamic of . . . .Jesus' self-gift [through the] sharing in his body and blood.” (13).

Coming full circle, reception grows into participation. By this participation, we are conformed and transformed; to receive Christ, whose name is “caritas,” is to become Christ, charity in thanksgiving (1 Jn 4:8; DCE §12). This is not only “right and just,” but it is our “duty and our salvation” (Eucharistic Prayer II). “Contemplating [by our lives] the precious blood of Christ, the sign of his self-giving love (cf. Jn 13:1),” we approach our elevated end: we perceive, receive, and visibly manifest the “almost divine dignity of every human being,” for the “service and glory of the Father” (EV §25; CCC §1698).

What’s at Stake: The Drama of Salvation

Love of neighbor is a path that leads to the encounter with God . . . closing our eyes to our neighbor . . . blinds us to God. (Deus Caritas Est §16)

Balthasar’s dramatic aesthetics, then, culminates when mystagogy becomes sacramental. That is, our participation becomes efficacious, transformative, and ultimately salvific. Human dignity as a revealed reality follows this progression; to adhere to the fact of human dignity means to unite oneself to the charity of Christ, to kenotically outpour oneself for one’s neighbor. Consequently, the matter of human dignity is closely linked with the grave matter of our salvation. But again, the receptive participation in this reality is necessarily preceded by perception. And, in our freedom, we may choose to close our eyes to human dignity. We may abstain from perceiving, receiving, and revealing it. We may opt for the pretty path of self-preservation rather than the beautiful way of self-outpouring.[4] In fact, we may even choose to veil the truth of human dignity, as did the parabolic robbers, priest, and Levite in their violence and neglect toward their neighbor.

Before the Samaritan enters the scene, we behold the desecration of human dignity, the denial of relationship and correlativity (See: Pfeil). This parabolic figure signals the real tragedy still being experienced by humankind, which Pope John Paul II declares “the eclipse of the sense of God and of man” (EV §21). It is evinced by the darkness of isolation, poverty, disease, scarcity, underdevelopment, and death (DCE §19; EV §10; Fratelli Tutti §§9-55). This is what is at stake in the discussion of human dignity. God has set before us the choice to perceive or ignore, participate or reject, reveal or veil. Should we fail to perceive, we will fail to respond in keeping with our shared dignity (CCC §1698).

If the discourse on human dignity crucially boils down to a matter of perception in terms of veiling or unveiling, one could point out that human dignity is, at least in part, perceptible to unaided human sight. Without the light of revelation, we can recognize evidence for humanity’s special dignity through the unique intelligence and freedom of the human among creation. Furthermore, human dignity is accessible on an intuitive level; it resides in the human conscience, the “natural law written in the heart” (EV §2; Rom 2:14-15). Thanks to this perception at the natural level, “reason, by itself, is capable of grasping the equality between men and of giving stability to their civic coexistence” (DCE §19). This basic recognition of our dignity shapes our human and political communities and grounds much needed social justice work (EV §2).

Nevertheless, as Pope Benedict XVI avers, while unaided reason serves an integral role in establishing “civic coexistence . . . it cannot establish fraternity. This originates in a transcendent vocation from God the Father, who loved us first, teaching us through the Son what fraternal charity is.” The human vocation reaches its apex, not at the height of earthly gains, but at the “unity in the charity of Christ who calls us all to share as sons in the life of the living God, the Father of all” (DCE §19). Thus, while unaided reason can perceive something of human dignity, its vision is short-sighted, “enclosed in the narrow horizon of . . . physical nature” (EV §22).

Consequently, the response will fall short of humanity’s transcendent call to caritas. If we view our neighbor through a lens of equality rather than loving preference, we will invariably respond in a manner mindful of our own selves; in the I-Thou encounter, “I” remains a dominant component in the equation. Our attitude will resound that of the scholar from Luke’s Gospel, seeking the bare minimum of loving required to preserve oneself.

The voice of love renounces this: “Whoever seeks to preserve his life will lose it, but whoever loses it will save it” (Lk 17:33). To fall short of a loving response to the dignity of the other is to fall short of our participation in and union with love—the content of “eternal Life,” the form of salvation. The most full response to our human dignity, then, can only be reached in the graced light of revelation, which emanates from Christ’s side, rains down upon our lowly heads. It runs into our eyes, washing away obscurity so that, lifting our gaze, we might contemplate him. Von Balthasar puts it thus:

Christian action is above all a secondary reaction to the primary action of God toward man . . . If God’s prior action were not presupposed, our deed would have to take its measure from the identity of human nature, from a consideration of the inevitable limitation from equalizing the interests of the I and the Thou . . . Because God has given to me without counting the costs, to the point of wholly losing himself (Mt 27:46), I must surrender any worldly calculation of the relationship between almsgiving and compensation (Mt 6:1-4; 6:19-34); the standard that God lays down becomes the standard that I must lay down, and thus the standard by which I myself am measured. This is not a principle of “mere justice,” but the logic of absolute love.[5]

Human Dignity Unveiled

To be clear, the aesthetic logic of absolute love does not reject justice. Justice is intrinsic to charity and demanded by it; it is the “minimum measure” of charity (Caritas in Veritate §6). However, as charity flows in the logic of total generosity, it quickly surpasses the minimum standard. In the gaze of charity, we contemplate a vision of human dignity that presents, if not an other-worldly, a trans-worldly and almost divine order. The vision of human dignity looks like mercy over justice, preference of the other over oneself, persons over efficiency, being over having, giving over acquiring (EV §§87-90).[6]

It is revealed in humble gestures and in the reconciliation of estranged neighbors—all impossible but for God’s grace. It radiates through saints like Teresa of Calcutta, Oscar Romero, and Francis of Assisi, who, by living the beatitudes, “depict the countenance of Jesus Christ and portray His charity” (DCE §40; CCC §1717). The vision of human dignity looks, tastes, feels, smells, and sounds like an aesthetic of solidarity: a hope opened to us by the victim’s ostensibly foolish utterance of forgiveness, blooming toward its final end of Holy Communion (Lk 23:34).[7]

Charity Is the Most Credible Witness

The truth of human dignity lies in the intersection of humanity and God. And, though described as “human,” our dignity is principally and ultimately a reality of God’s love. For, the event of this intersection of God-and-humankind is owed first to God’s gratuitous and merciful condescension toward us (not the reverse). It is made possible, not by our effort or worthiness but by Christ’s charity-in-truth. He deigned to dwell among us, taking on the form of our neighbor and binding himself to our lowliness. “Human dignity,” then, is hardly an estimation of human value, but rather a reality bound up in the revelation of Christ’s unbounded charity.

In his revelatory self-disclosure, we discover that this intersection of God and man is not theoretical but incarnational, most real and substantial. He pours out his precious blood into the abyss of our lack, showing us that we are dignus, worthwhile, to him simply because he loves us. By our living contemplation of this “perfect correspondence between divine and human love in the Son,” we are incorporated into this “perfect measure.” Thanks to his forgiveness, our human short-sightedness has “already been overcome and compensated for, so that out of faith, we can bring ever more fully to life in Christian activity that which God’s holy grace has always already allowed us to be in is eyes”: charity incarnate.[8]

Such a “sacramental ‘mysticism’, grounded in God's condescension towards us, operates at a radically different level and lifts us to far greater heights than anything that any human mystical elevation could ever accomplish” (DCE §13). The Christian aesthetic of human dignity makes visibly present a love that transcends our estimation by its ever-enduring generosity. Giving ourselves over to the form of this neighborly, dignified, and dignifying love by our lives is more than just a way of seeing human dignity among other perspectives. It is the most authentic and compelling, the most credible witness to human dignity. It reveals the essential love encounter between charity incarnate and humanity, the beauty of which manifests as an irresistible love response.

[1] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Love Alone Is Credible (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2015), 72.

[2] Ibid., 77.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 97-98.

[5] Ibid., 112-113.

[7] Goizueta, Roberto S. Christ Our Companion: Toward a Theological Aesthetics of Liberation. United States, Orbis Book s, 2009, Ch. 6, “Reimagining the border”, 16.

[8] Von Balthasar, 104.