There are some stereotypes that often accompany the college stage of a woman’s life. Some (like loving babies, studying in coffee shops, etc), I embraced. Others I did my absolute best to avoid (and we'll leave those ones to the imagination). My friends and I all proudly took up an affection for and gravitation toward all infants and young children within a mile radius as our stereotypical banner of choice. In fact, we had an unspoken arrangement that involved immediately informing each other of the presence of any nearby bundle(s) of joy. My girlfriends and I reveled in the wonder that small children have; we discussed how there is nothing on this earth more precious than tiny fingers, toes, and noses; we felt the urge to play peek-a-boo with any and all small children who crossed our paths. And if we saw a little tyke just wobbily learning to walk, it was absolutely the game-over-highlight of our day. Not having children of our own yet meant that we certainly still had a somewhat romanticized view of young children and parenthood, but we honestly meant well, and the call of Jesus to “let the little children come” resonated with us.

At Christmas, that love and the gravitational pull of my heart towards little ones seasonally intensifies. And every year, the fact that our Lord came to earth not as an adult but as a helpless, innocent, dependent little one who needed the arms of his mother Mary and his foster-father Joseph repeatedly stuns me.

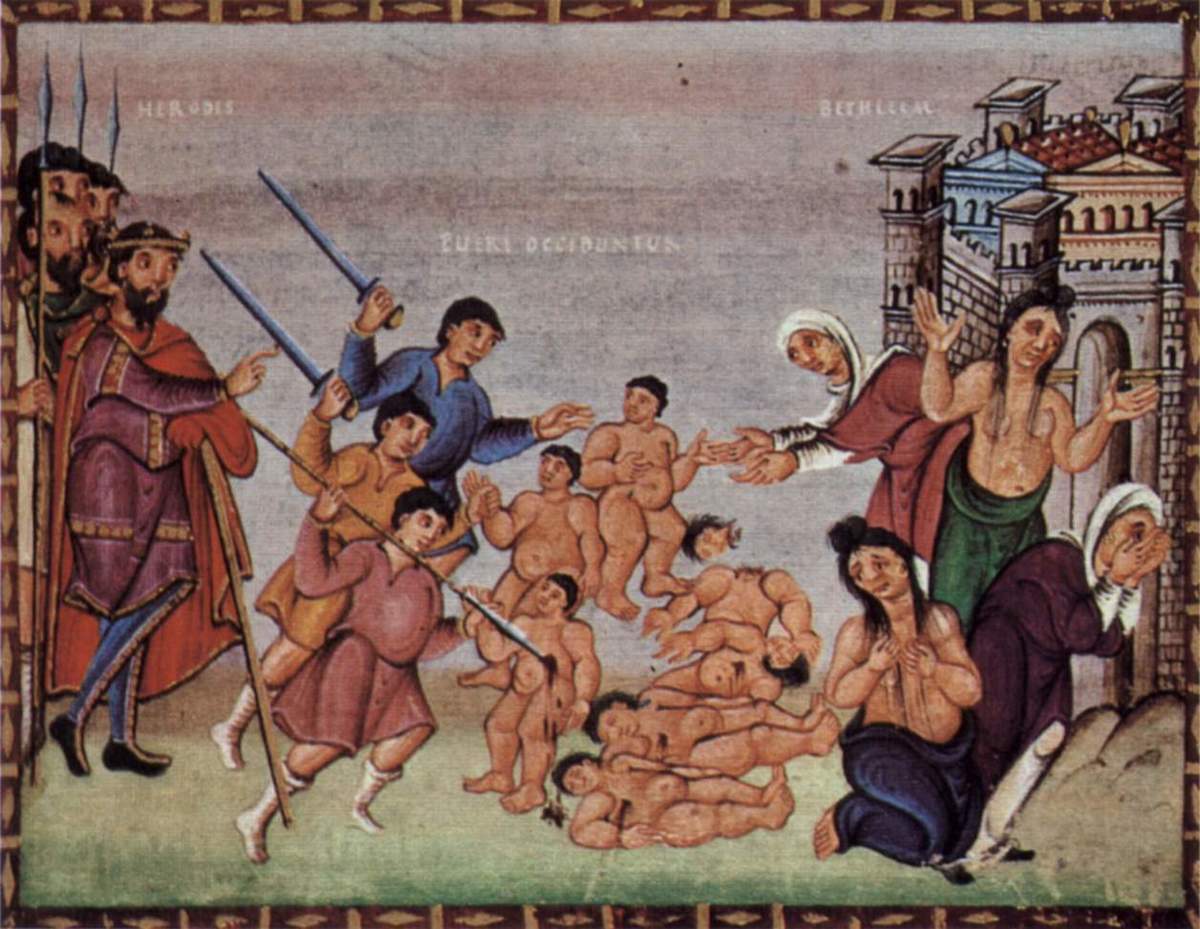

But the Feast of the Holy Innocents is not warm and fuzzy. This feast is not a day where we can blithely wonder what it would have been like to count the toes of baby Jesus and to kiss his head. The Church commemorates the Feast of the Holy Innocents, as it has been doing so since at least the fifth century. The Gospel of Matthew helps us to remember that Joseph and Mary left a dire situation when they fled with Jesus toward Egypt:

When Herod realized that he had been deceived by the magi,

he became furious.

He ordered the massacre of all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity

two years old and under,

in accordance with the time he had ascertained from the magi.

Then was fulfilled what had been said through Jeremiah the prophet:A voice was heard in Ramah,

sobbing and loud lamentation;

Rachel weeping for her children,

and she would not be consoled,

since they were no more. (Mt 2:16–18)

How can this day—a day when we remember the martyrdom of infant and toddler baby boys who died in Jesus’ stead because of Herod’s fear, wrath, and pride—fit in with the love of children, littleness, and humility that permeates the very foundations of our faith at Christmas? Why do we celebrate and remember a day when infant boys were massacred? We were reminded in the Office of Readings on Christmas of a sentiment that at first glance might not seem to fit with today:

Dearly beloved, today our Savior is born; let us rejoice.

Sadness should have no place on the birthday of life. (St. Leo)

Yet here we are, only a few days later, remembering the mothers who "wept with Rachel," and aching for the infants whose lives were cruelly snuffed out by Herod’s soldiers. How are we supposed to reconcile that brutal fact and painful reality with warm and fuzzy feelings of Christmas?

Put simply, we don’t.

St. Leo's sermon on Christmas did not end with telling us sadness should have no place in the Christian life ever because of the feast of Christmas. The next line continues the story:

The fear of death has been swallowed up;

life brings us joy with the promise of eternal happiness.

That is what makes the reality of the Holy Innocents livable. If we reduce Christmas to feelings of togetherness and cheerfulness, or if we disable the mystery of the Incarnation and cripple it to fit in our boxes of gift giving and kitchens full of holiday smells, it will become impossible to reconcile the deaths of the little ones with a good God in faith. Instead, if we remember that the Incarnation actually means that our Savior became flesh and came to dwell among us, and that he was born in order that he could die for us so that we could have the hope of eternal glory, the narrative shifts. It shifts from one that would despair at the death of the Holy Innocents to one that celebrates and remembers them, counting them as martyrs, knowing that they did not die in vain.

St. Bede, the Doctor of the Church who is often mentioned for his “Ecclesiastical History of the English People” but who wrote enough to fill a library, penned a Latin hymn in memory of the infant martyrs whom we commemorate today entitled Hymnum canentes martyrum. His hymn captures that narrative shift. This shift enables us to realize that Christmas is not about the saccharine fuzziness that we might societally associate it with, but rather the hope of heaven that became reality because our God became flesh, and dwelt among us, for us.

A Hymn for Martyrs sweetly sing;

For Innocents your praises bring;

Of whom in tears was earth bereaved,

Whom heaven with songs of joy received

Whose angels see the Father’s face

World without end, and hymn His grace;

And, while they praise their glorious King,

A hymn for Martyrs sweetly sing.A voice from Ramah was there sent,

A voice of weeping and lament,

While Rachel mourned her children sore,

Whom for the tyrant’s sword she bore

After brief taste of earthly woe

Eternal triumph now they know;

For whom, by cruel torments rent,

A voice from Ramah was there sent.And every tear is wiped away

By your dear Father’s hands for aye:

Death hath no power to hurt you more;

Your own is life’s eternal shore

And all who, good seed bearing, weep,

In everlasting joy shall reap,

What time they shine in heavenly day,

And every tear is wiped away.

Bede’s hymn and our knowledge in faith does not mean that we shrug our shoulders at the pain and the injustice of the slaughter of the Holy Innocents; it does not mean that Herod (or his modern-day counterparts) gets a free pass. It does, however, mean that the meaning of the Incarnation is held together because of the Paschal Mystery. And that’s why when we hear of the deaths of the Innocents, we might still cry. But we can cry with hope, knowing that there is a place where every tear is wiped away.

The birth of our Savior has ripped apart the fabric of time. By his later Death and Resurrection, the little one whose birth we celebrated only days ago saved the souls of the infants who died as Herod greedily tried to salvage his earthly power. And so when those baby boys died, they did not die in vain, but in the hope and promise of eternal life. We celebrate their memory as some of the first martyrs of our faith, knowing that our God can write straight with even the most crooked and sad lines of history.