In Pope Francis’s amendment to the Catechism’s §2267, we see a sense of progressive development applied to the Church in the world. That we should only now fully realize “in the light of the Gospel” that the death penalty is inadmissible is likely to elicit concern from those wary of novelty. Pope Francis’s letter to the bishops concerning this change points out that this language should be no surprise, since similar things were said on the subject by Pope Saint John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI, as well as by the Pontifical Biblical Commission in 2008 in its document The Bible and Morality:

In the course of history and of the development of civilization, the Church too, meditating on the Scriptures, has refined her moral stance on the death penalty and on war, which is now becoming more and more absolute. Underlying this stance, which may seem radical, is the same anthropological basis, the fundamental dignity of the human person, created in the image of God (Bible and Morality: The Biblical Roots of Christian Conduct, §98.3).

Many will perceive the appeals to theological development and phrases like the fundamental dignity of the human person as more pieces of flotsam in a misbegotten tide of barely meaningful theologoumena. Or worse, some will take this addition to the Catechism as another painful example of Pope Francis’s tyranny of ambiguity.

The current theological argument about the death penalty brings with it a whole host of issues regarding not only temporal authority and the common good, but the relation of those two realities to the spiritual authority of the Church. It raises the specter of unfinished conversations on religious liberty like the debate between Thomas Pink and Martin Rhonheimer that took place in the pages of the journal Nova et Vetera and here at the Notre Dame’s Center for Ethics and Culture Fall Conference. More broadly, it invokes the reemerging quarrel between Christianity and liberalism highlighted recently in conferences at Harvard and Paris.

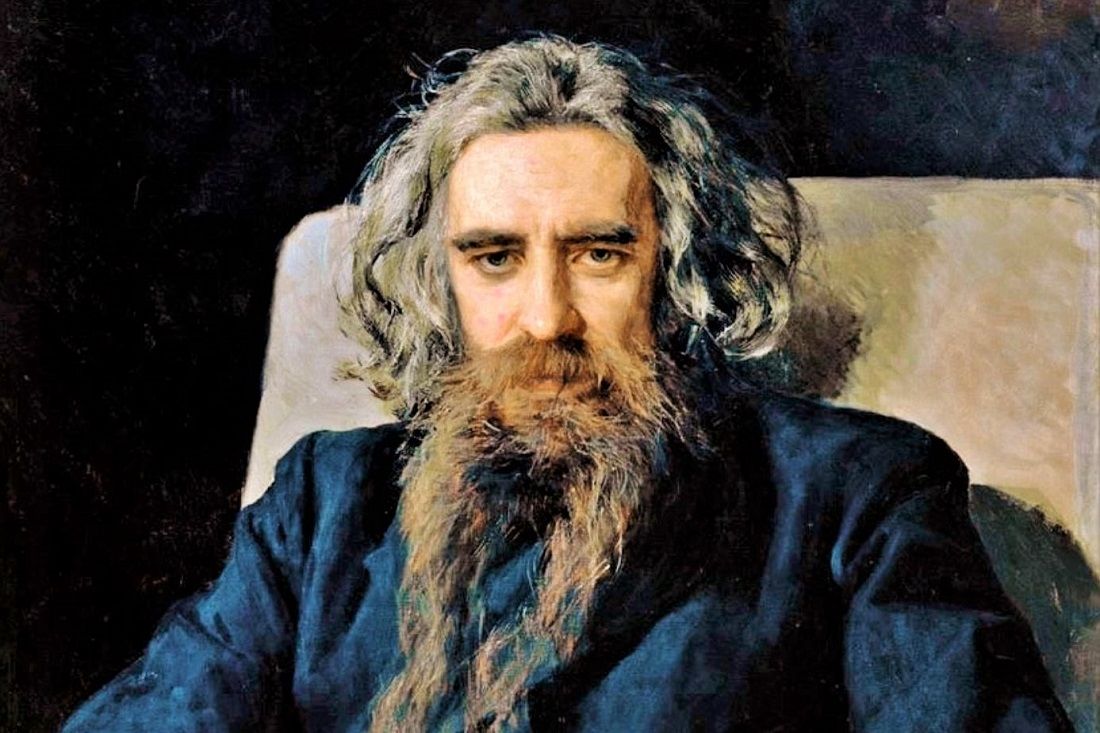

I would like to make a modest contribution to the particular debate on religious liberty by reflecting on the writings of the Russian theologian, philosopher, and mystic Vladimir Solovyov. While he had arguments that were more strictly philosophical and pragmatic, it is his exegetical and theological arguments that are both more persuasive and more pertinent to the teachings of the previous two popes on capital punishment.

In his work Morality and Legal Justice, Essays on Practical Ethics, Solovyov sets out to dismantle justification for the death penalty from every angle. From the vantage point of theology, Solovyov thought it critical to define the paradigm in which Scripture applies to specific ethical questions. To speak of the Bible in general as being for or against something, especially in the case of capital punishment, was for him “a sign either of hopeless lack of understanding or of boundless insolence.” He argued that verses like Gen. 9:6 (Whoever sheds man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed) or the various prescriptions for capital punishment in Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy cannot possibly be proof-texts for contemporary defenses of the death penalty.

Determining the significance of scriptural passages cannot be simply a matter of piling up proof-texts and singular instances. Instead, we must understand that the Bible:

. . . is a complex spiritual organism that has taken a thousand years to grow; it is completely devoid of external uniformity and exactitude, but remarkable for the inner unity and harmony of the whole. Arbitrarily to snatch out of this whole intermediary parts without beginning or end is a false and meaningless procedure.

A theological analysis of Scripture works within the framework of organic development, both within the canon of Scripture and in the development of dogma within the matrix of the Church and its liturgy performed throughout history.

Anticipating both Rene Girard’s Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World and Giorgio Agamben’s Homo Sacer, Solovyov reminded his readers that there is a powerful thread of savagery linking certain forms of law and religion to the idea of the sacred and of sacrifice. While Christianity is “no bloodless myth” it purifies sacrificial worship into the rational, spiritual, and unbloody liturgy of the Eucharist. Solovyov posits that this shadow of penal substitutionary atonement “still exercises a hidden influence upon conservative minds, precisely in the question of capital punishment.” His main target in this case would have been Joseph de Maistre, but it applies to anyone who thinks that the state’s use of the death penalty is a participation in the economy of salvation.

Even those who rightly shrink back from this dark vision, may echo de Maistre in a lesser way by maintaining that those guilty of heinous crimes must be killed because they deserve to be killed and to do otherwise would be to paper over the nature of reality. Solovyov’s criticism of the death penalty was partly a matter of development of the truths of Christianity, but it was also a recalling of a more accurate image of justice displayed in the Gospels. The widespread acceptance of the death penalty in Christian nations was a shameful forgetting and not simply a matter unknowable until further clarification.

Solovyov’s understanding of inner-Scriptural development makes the account of Cain and Abel the paradigm for God’s desire to absolutely prohibit the death penalty. Abel’s blood cries out to heaven and God gives retribution for the hideous fratricide by banishing Cain. But by no means does this give any man (not even his father, Adam) the right to kill Cain for his crime. This is not, for Solovyov, a case of God’s mercy but rather the promulgation of a norm for the limits of legal and moral human retribution.

In Evangelium Vitae, John Paul II also made use of the story of Cain and Abel within the context of the death penalty:

The sacredness of life gives rise to its inviolability, written from the beginning in man's heart, in his conscience. The question: "What have you done?" (Gen 4:10), which God addresses to Cain after he has killed his brother Abel, interprets the experience of every person: in the depths of his conscience, man is always reminded of the inviolability of life-his own life and that of others-as something which does not belong to him, because it is the property and gift of God the Creator and Father (§39).

In this section of the encyclical, John Paul II also adopts a similar model of inner-Scriptural development. The Holy Father calls the usual passages marshalled for the death penalty part of the unrefined material of the Old Testament whose lasting significance is in its recognition of the profanity of murder and must wait for the Sermon on the Mount to achieve unalloyed perfection.

In a similar manner, Solovyov thinks that only Christ can reveal the absolute and perfect communication of God’s will and that the Old Testament must be read in light of the New. Christ himself introduces this possibility of abrogated moral allowances in his debate with the Pharisees over divorce. Matthew 19:8 is a crucial moment that reveals that what may have been conditionally permissible during the time of Noah, Abraham, and Moses, “was not that way from the beginning” and will no longer be permissible. Some of the early fathers like Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, connected this saying of Jesus with Jeremiah 7:22 and Ezekiel 20:25 and formulated the idea of diverse imperfect pedagogical disciplines within the larger perfect unity of God’s salvific economy.[1]

Like them, Solovyov, understood that even before Christ an inner dialectic within the Jewish Scriptures was revealing both a return a moving beyond certain regulations and precepts. For Solovyov in particular, this included the norm seen in the example of Cain in Abel even as early as the Song of Moses we hear “Vengeance is mine; I will repay, says the Lord.” And of course the day of God’s vengeance so palpably figured forth throughout the prophetic discourses is revealed by Peter’s reading of Joel 2:28-32 at Pentecost. God works in mysterious ways and his vengeance is no exception. The vengeance God chose was the death and resurrection of his Son and the pouring out of his Spirit on all flesh. At this the elements of the world trembled, the cosmic dawn of the end of all things.

Vladimir Solovyov has played the forerunner to these developments. It is plausible to think that he directly influenced John Paul II on the question of the death penalty. In 2000, Pope John Paul II dedicated an Angelus address to Solovyov, and in 2003 he gave a speech to the participants of the convention given in honor of the 150th anniversary of Solovyov’s birth. Vladimir Solovyov also appears in the encyclical Fides et Ratio as an exemplary practitioner of Christian philosophy. The similar structure of John Paul II’s argument in Evangelium Vitae, even down to particular examples, makes it difficult to maintain that there was no influence. If true, it would be a beautiful example of a Russian lover of the Petrine office offering a gift to the Universal Church that only came to fruition after his own death.

As a concession to those of a more stringent theological temperament, I admit that the Church’s official teachings have rarely set forth a full narrative of how previous accounts of the death penalty, religious liberty, and Church-state relations were not just imperfect but in some cases the exact opposite of what they are now. It does no one any good to deny that the death penalty in general and the execution of heretics in particular was defended not just as good theology but as possibly a matter of the depositum fidei. Only by asserting that what was previously formulated only occasionally by papal pronouncements is now corrected by two of the most official teaching organs of the Church, an ecumenical council and the direct emendation of a matter of faith and morals into the universally promulgated Catechism of the Catholic Church.

It is a labor for those of us who champion a model of authentic development to deal in the particulars of Church history and the theologians of all ages and present a plausible account of how this progress took place. To eschew this work is to cede ground to those who claim that developments “in the light of the Gospel” is simply code for indexing moral theology to public opinion.

Featured Image: Nikolai Yaroshenko Portrait of philosopher Vladimir Solovyov. 1895; Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD-Old-100.

[1] See: Michael Barber, “The Yoke of Servitude: Christian Non-Observance of the Law’s Cultic Precepts in Patristic Sources”, Letter and Spirit 7 (2011).