If I seem to take N.T. Wright as an antagonist in what follows, he functions here only as emblematic of a larger historical tendency in New Testament scholarship. I can think of no other popular writer on the early church these days whose picture of Judaism in the Roman Hellenistic world seems better to exemplify what I regard as a dangerous triumph of theological predispositions over historical fact in biblical studies—one that occasionally so distorts the picture of the intellectual and spiritual environment of the apostolic church as effectively to create an entirely fictional early Christianity. Naturally, this also entails the simultaneous creation of an equally fictional late antique Judaism, of the sort that once dominated Protestant biblical scholarship: a fantastic “pure” Judaism situated outside cultural history, purged of every Hellenistic and Persian “alloy,” stripped of those shining hierarchies of spirits and powers and morally ambiguous angels and demi-angelic nefilim that had been incubated in the intertestamental literature, largely ignorant even of those Septuagintal books that were omitted from the Masoretic text of the Jewish bible, and precociously conformed to later rabbinic orthodoxy—and, even then, this last turns out to be a fantasy rabbinic orthodoxy, one robbed of its native genius and variety, and imperiously reduced to a kind of Protestantism without Jesus.

No such Judaism ever existed, either in the days of Christ and the apostles or in any other period; but it has enjoyed a long and vigorous life in Protestant dogmatics and biblical criticism. And I was recently reminded of this by Wright himself, when he publicly objected to a footnote in my own recent translation of the New Testament. In that note, I mentioned more or less in passing that Paul seems to have thought that some of the narratives of the Jewish Bible not only were apt for allegorical readings, but might also have originally been written as allegories. For Wright, this was tantamount to a suggestion that Paul did not believe in the reality of God’s covenants with Israel. Now, needless to say, nothing of the sort follows logically from my observation; more to the point, my footnote did nothing more than call attention to Paul’s own words. (And, really, how often does Paul not employ allegory in reading scripture?) But Wright’s anxiety is quite in keeping with a certain traditional Protestant picture of the pagan and Jewish worlds of late antiquity, one that involves an impermeable cultural partition between them—between, that is, the “philosophy” of the Greeks and the “pure” covenantal piety of the Jews. And, as I say, the results are sometimes comic. Unfortunately, they are at other times positively disastrous. Nowhere is this more strikingly the case—and nowhere does Wright’s work in particular present a more troubling specimen of pious exegetical violence to scripture—than in regard to the New Testament’s use of the words πνεῦμα (spirit), ψυχή (soul), and σάρξ (flesh), as well as to the theologies of resurrection that attach to them.

We are, of course, far removed from the world of the first century, and so it is natural for us, when we encounter these words and others like them in the New Testament, to see them as having only very vague imports, apposite to mistily ill-defined concepts or spectrally impalpable objects. We almost invariably etherealize or moralize their meanings in ways that entirely obscure the picture of reality they originally reflected. The earth on which we live, for example, is not divided from the several heavenly spheres by the lunary sphere, nor is the aerial realm of generation and decay here below separated by that sphere from the imperishable ethereal realm of spiritual forces there above. Thus, for us today, even such words as “heavenly” (ἐπουράνιος) and “earthly” (χοϊκός) convey practically nothing of the exquisite cosmology—at once concretely physical and vibrantly spiritual—in which the authors of the New Testament lived. And inevitably, when we read of “spirit,” “soul,” and “flesh” in the New Testament, the specter of Descartes (even if unnoticed by us) imposes itself between us and the conceptual world those terms reflect; we have next to no sense of the implications, physical and metaphysical, that such words had in the age of the early church. Even “flesh” becomes an almost perfect cipher for us, not only because we lack the perspective of ancient persons, but also because of the drastic oversimplifications of Christian tradition with which we have been burdened; we think we know—just know in our bones—that the early Christians unambiguously affirmed the inherent goodness of the material body, and that surely, then, Christian scripture could never have meant to employ the word “flesh” with its literal acceptation in order to designate something bad. Thus, as we read along, either we convince ourselves not to notice that almost every use of the word is openly opprobrious, and that the very few that are not are still for the most part merely neutral in intonation, or we acknowledge this fact but nevertheless still insist to ourselves that the word is being used metaphorically or as a lexical synecdoche for some larger conceptual construct like “the mortal life in the flesh, stained with sin and lying under divine judgment.”

In the world of Protestant scriptural scholarship, this latter strategy reached a kind of cartoonish climax in the early editions of the New International Version of the Bible, where the word “flesh” was in many cases rendered as something like “sinful nature” (I would check the exact wording, but that would involve picking up a copy of the NIV). This is utter twaddle. In the New Testament, “flesh” does not mean “sinful nature” or “humanity under judgment” or even “fallen flesh.” It just means “flesh,” in the bluntly physical sense, and it often has a negative connotation because flesh is essentially a bad condition to be in; belonging to the realm of mutability and mortality, it can form only a body of death. Hence, according to Paul, the body of the resurrection is not one of flesh and blood animated by “soul,” but is rather a new reality altogether, an entirely spiritual body beyond composition or dissolution. And this is how his language would have been understood by his contemporaries.

To grasp this fully today, however, one really has to take leave of the Cartesian picture of things. One must cease to think that only the material body possesses extension in any sense; one must learn not to treat words like “soul,” “spirit,” and “mind” as interchangeable terms for one and the same thing; and one must most emphatically not think of soul or spirit or mind as necessarily incorporeal in the absolute sense of lacking all extension or consistency. None of this resembles the ancient view of things. And one must be especially conscious that the words πνεῦμα and ψυχή were not nebulous terms in the religious or speculative vocabulary of the Hellenized world; neither in most cases were they likely to be confused with one another, as “spirit” and “soul” can be in modern English, because they were usually used as precise names for two distinct principles that were not only already resident in the created cosmos; in some systems of thought, in fact, they named principles practically antithetical to one another in their metaphysical and religious meanings. In different eras, places, and schools, admittedly, each of these words carried somewhat different, if never entirely unrelated, connotations; but each word always had a clear significance. And Paul used both terms in ways that were very much part of the philosophical and scientific lingua franca of his age. In the broader system of ideas in which his picture of things subsisted, “soul”—ψυχή or anima—was chiefly the life-principle proper to the realm of generation and decay, the “psychical” or “animal” substance that endows sublunary organisms with the power of self-movement and growth, though only for a short time. And the bodily life produced by this “animating” principle was understood as strictly limited to the aerial and terrestrial sphere. It could exist nowhere else, and most certainly not in the heavenly places. It was too frail, too ephemeral, too much bound to mutability and transience.

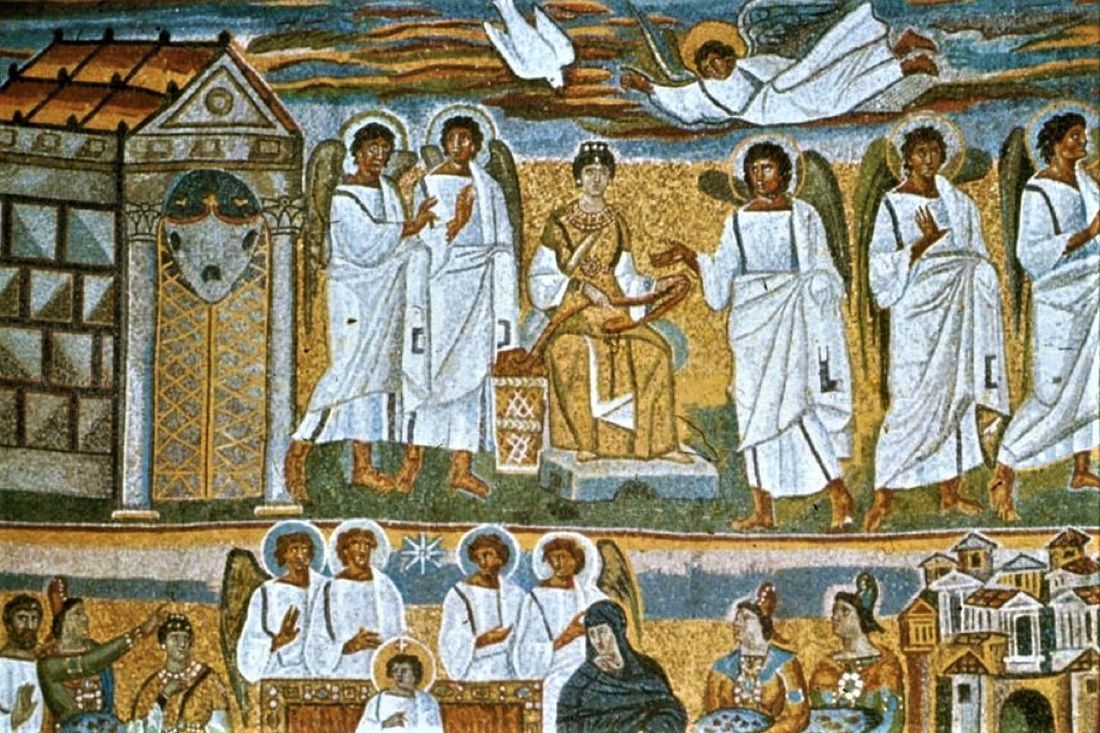

“Spirit,” by contrast—πνεῦμα or spiritus—was something quite different, a kind of life not bound to death or to the irrational faculties of brute nature, inherently indestructible and incorruptible, and not confined to any single cosmic sphere. It could survive anywhere, and could move with complete liberty among all the spiritual realms, as well as in the material world here below. Spirit was something subtler but also stronger, more vital, more glorious than the worldly elements of a coarse corruptible body compounded of earthly soul and material flesh. Thus too the word “spirits” was common parlance in late antiquity for all those rational personal agencies and entities who populated the cosmos but who were not bound to vegetal or animal bodies, and so were immune to death: lesser celestial gods, daemons, angels, nefilim, devils, or what have you (what one called the various classes of spirits was a matter of religious vocabulary, not necessarily the basic conceptual shape of their natures). These beings enjoyed a life not limited by the conditions of the lower elements (the στοιχεῖα) or of any of the intrinsically dissoluble combinations thereof.

Even so, none of these beings was typically considered to be incorporeal in the full sense, at least in the way we would use that word today. The common belief of most educated persons of the time was that, if any reality was bodiless in the absolute sense, it could be only God or the highest divine principle. Everything else, even spirits, had some kind of body, because all of them were irreducibly local realities. The bodies of spirits may have been at once both more invincible and more mercurial than those with an animal constitution, but they were also, if in a peculiarly exalted sense, still physical. Many thought them to be composed from, say, the aether or the “quintessence” above, the “spiritual” substance that constitutes the celestial regions beyond the moon. Many also identified that substance with the πνεῦμα—the “wind” or “breath”—that stirs all things, a universal quickening force subtler even than the air it moves. It was generally believed, moreover, that many of these ethereal or spiritual beings were not only embodied, but visible. The stars overhead were thought to be divine or angelic intelligences (as we see reflected in James 1:17 and 2 Peter 2:10-11). And it was a conviction common to a good many pagans and Jews alike that the ultimate destiny of great or especially righteous souls was to be elevated into the heavens to shine as stars (as we see in Daniel 12:3 and Wisdom 3:7, and as may be hinted at in 1 Corinthians 15:30-41). In the Jewish and Christian belief of the age, in fact, there really appears to have been nothing similar to the fully incorporeal angels of later scholastic tradition—certainly nothing like the angels of Thomism, for example, who are pure form devoid of prime matter and therefore each its own unique species.

In fact, it was a central tenet of the most influential angelology of the age, derived as it was from the Noachic books of the intertestamental period, that angels had actually sired children—the monstrous nefilim—on human women. It is even arguable that no school of pagan thought, early or late, perhaps not even Platonism, really had a perfectly clear concept of any substance without extension. For Plotinus, for instance, “soul” was “incorporeal,” but not in the way we might assume; while the soul in Plotinus’s system was not susceptible of “material” magnitude, and hence could contain all forms without spatial extension (Enneads 2.4.11), it was still “incorporeal” only in the sense that it possessed so subtle a nature that it could wholly permeate material bodies without displacing their discrete material constituents (Enneads 4.7.82). Neither “spirit” nor “soul” was anything quite like a Cartesian “mental substance.” Each, no less than “flesh and blood,” was thought of as a kind of element. “Spirit,” for instance, in certain antique schools of natural philosophy and medicine, could be defined as that subtle influence or ichor that pervades the veins and passages of a living body and, among other things, endows it with sense perception—by filling, for instance, the nerves or porous passages between eye and brain. For many persons, in fact, this vital influence was literally “physically” continuous with the “wind” that fills the world and the “breath” that swells our chests. This is almost unimaginable for us, of course.

When today, for instance, we try to make sense of John 3:8, we are frustrated by the absence in English of any word adequate to all the meanings present in the original’s use of πνεῦμα. The Greek reads: τὸ πνεῦμα ὅπου θέλει πνεῖ καὶ τὴν φωνὴν αὐτοῦ ἀκούεις, ἀλλ’ οὐκ οἶδας πόθεν ἔρχεται καὶ ποῦ ὑπάγει· οὕτως ἐστὶν πᾶς ὁ γεγεννημένος ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος. My attempt at a rendering in my translation, whose inadequacy I sheepishly acknowledge in my footnote thereto, is this: “The spirit respires where it will, and you hear its sound but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes; such is everyone born of the Spirit.” I could, however, in each instance have written not “spirit” for πνεῦμα, but “wind” or “breath”; instead of “respires” for πνεῖ, I could have written “blows.” Perhaps, then, this: “The wind blows where it will . . . such is everyone born from the wind.” Or, perhaps, “The breath breathes where it will . . . such is everyone born from the breath.” Happily, no translators have yet visited anything like that on us. But, still, all the various possible meanings would have been audibly present in the text for its author and for those who heard it read aloud in the earliest Christian communities. Even if we are aware of this, however, we are still likely to read the verse as a kind of play on words—at most, an illustrative simile. And, needless to say, our fully formed theological concept of the Holy Spirit disposes us, on grounds of piety alone, to see it as such. But it probably should not really be taken as wordplay at all.

If we could hear the language of πνεῦμα with late antique ears, our sense of the text’s meaning would not be that of two utterly distinct concepts—one “physical” and one “mystical”—only metaphorically entangled with one another by dint of a verbal equivocity; rather, we would almost surely hear only a single concept expressed univocally through a single word, a concept in which the physical and the mystical would remain undifferentiated. To be born of spirit (or Spirit), to be born of the wind of life, to be born of the divine and cosmic breath vivifying and uniting all things—it would all make perfectly simple, straightforward, “physical” sense to us. Whatever the case, though, this much is certain: it was widely believed in late antiquity that, in human beings, flesh and soul and spirit were all present in some degree; “spirit” was merely the element that was imperishable by nature and constitution.

This is why it is that those traditional translations of 1 Corinthians 15:35-54 that render Paul’s distinction between the σῶμα ψυχικόν (psychical body) and the σῶμα πνευματικόν (spiritual body) as a distinction between “natural” and “spiritual” bodies are so terribly misleading. The very category of the “natural” is otiose here, as would be any opposition between natural and supernatural modes of life; that is a conceptual division that belongs to other, much later ages. For Paul, both psychical and spiritual bodies were in the proper sense natural objects, and both in fact are found in nature as it now exists. He distinguished, therefore, not between “natural” and “spiritual” bodies, but only between σώματα ἐπίγεια (“terrestrial bodies”) and σώματα ἐπουράνια (“celestial bodies”). And this, again, is a distinction not between natural and supernatural life, but merely between incommiscible “natural” states: ἀφθαρσία (“incorruptibility”) and φθορά (“decay”), δόξα (“glory”) and ἀτιμία (“dishonor”), δυνάμις (“power”) and ἀσθένεια (“weakness”). In speaking of the body of the resurrection as a “spiritual” rather than “psychical” body, Paul is saying that, in the Age to come, when the whole cosmos will be transfigured into a reality appropriate to spirit, beyond birth and death, the terrestrial bodies of those raised to new life will be transfigured into the sort of celestial bodies that now belong to the angels: incorruptible, immortal, purged of every element of flesh and blood and (perhaps) soul.

For, as Paul quite clearly states, “flesh and blood cannot inherit the Kingdom of God; neither does perishability inherit imperishability”: σὰρξ καὶ αἷμα βασιλείαν θεοῦ κληρονομῆσαι οὐ δύναται οὐδὲ ἡ φθορὰ τὴν ἀφθαρσίαν κληρονομεῖ. And, of course, he also says that those who are in Christ have been made capable of this transformation precisely because, in the body of the risen Christ, the life of the Age to come has already appeared in glory: οὕτως καὶ γέγραπται· ἐγένετο ὁ πρῶτος ἄνθρωπος Ἀδὰμ εἰς ψυχὴν ζῶσαν, ὁ ἔσχατος Ἀδὰμ εἰς πνεῦμα ζῳοποιοῦν . . . ὁ πρῶτος ἄνθρωπος ἐκ γῆς χοϊκός, ὁ δεύτερος ἄνθρωπος ἐξ οὐρανοῦ. οἷος ὁ χοϊκός, τοιοῦτοι καὶ οἱ χοϊκοί, καὶ οἷος ὁ ἐπουράνιος, τοιοῦτοι καὶ οἱ ἐπουράνιοι· καὶ καθὼς ἐφορέσαμεν τὴν εἰκόνα τοῦ χοϊκοῦ, φορέσομεν καὶ τὴν εἰκόνα τοῦ ἐπουρανίου, “So it has also been written, ‘The first man Adam came to be a living soul,’ and the last Adam a life-making spirit . . . The first man out of the earth, earthly; the second man out of heaven. As the earthly man, so also those who are earthly; and, as the heavenly, so also those who are heavenly; and, just as we have borne the image of the earthly man, we shall also bear the image of the heavenly man.” This is for Paul nothing less than the transformation of the psychical composite into the spiritual simplex—the metamorphosis of the mortal fleshly body that belongs to soul into the immortal fleshless body that belongs to spirit: ἡμεῖς ἀλλαγησόμεθα. Δεῖ γὰρ τὸ φθαρτὸν τοῦτο ἐνδύσασθαι ἀφθαρσίαν καὶ τὸ θνητὸν τοῦτο ἐνδύσασθαι ἀθανασίαν, “We shall be changed. For this perishable thing must clothe itself in imperishability, and this mortal thing must clothe itself in immortality.”

It is not so much Christian dogmas as indurated habits of thought and imagination that make Paul’s language in 1 Corinthians 15 (or, for that matter, Romans 8) so impenetrable to modern Christians. No matter how clear Paul’s pronouncements are, the plain meaning of his words still seems so terribly “pagan” or “Platonic” or “semi-gnostic” to modern Christian ears, and of course all of those things are usually regarded as being very bad. Thus the picture persists of resurrection, even in Paul’s thought, as something along the lines of a reconstruction and reanimation of the earthly body. N.T. Wright, in the very odd and misleading translation of 1 Corinthians 15 that appears in his very odd and misleading The Kingdom New Testament, at one juncture turns σῶμα ψυχικόν and σῶμα πνευματικόν into, respectively, “embodiment of ordinary nature” and “embodiment of the spirit,” which is bad enough; but then the translation devolves further into a distinction between “the nature-animated body” and “the spirit-animated body,” which is simply atrocious. For one thing, the very word “animated” is deeply problematic, since it is arguably already a synonym for ψυχικόν, and since it is extremely unlikely—in fact, historically speaking, probably impossible—that Paul thought of the spiritual body as a kind of articulated organism, consisting in an extrinsic liaison between something animated and something animating. He almost certainly thought of “spirit” as being itself the substance that will compose the risen body, rather than an extrinsic life-principle that will come to reside in a revived and improved material body.

Wright, however, seems to imagine something like two different phases of some variety of Cartesian dualism, one mortal and the other immortal, but in either case involving the combination in a single composite of an animated material body and an animating immaterial force. This is the purest anachronism. Worse still, Wright follows a deeply misguided tradition of translation in imposing an opposition between “natural” and (one must suppose) “supernatural” on the text; that too, as I have said, is anachronistic. Worst of all, in his translation the central opposition between the two distinct principles of soul and spirit—which runs through the entire New Testament and which is crucial to its anthropology, theology, and metaphysics—has been entirely lost. But Wright has his own understanding of resurrection, one more or less consonant with the casually presumed picture today, even if it is one entirely alien to the world of first-century Judaism and Christianity. His categories are not those of Paul—or, for that matter, of the rest of the authors of the New Testament.

There is, admittedly, no single consistent account of resurrection—either Christ’s or ours—in the New Testament; but there is most definitely a prevailing tendency to view resurrection in terms quite similar to Paul’s. Only one verse, Luke 24:39, seems to advance a contrary picture; there, more or less reversing Paul’s terms, the risen Christ proves that he is not spirit precisely by demonstrating that he possesses “flesh and bone.” And even Luke, over the course of his books, seems somewhat inconsistent on the details. There is, at least, ample scriptural evidence suggesting that Paul’s language in 1 Corinthians 15 may be little more than a précis of a theology and metaphysics of resurrection not at all uncommon in many of the Jewish circles of his time. Certainly, his may have been one of the standard Pharisaic views of the matter. We almost unquestionably see evidence of this in Acts 23:8: Σαδδουκαῖοι μὲν γὰρ λέγουσιν μὴ εἶναι ἀνάστασιν μήτε ἄγγελον μήτε πνεῦμα, Φαρισαῖοι δὲ ὁμολογοῦσιν τὰ ἀμφότερα, “For the Sadducees say there is no resurrection—neither as angel nor as spirit—while the Pharisees profess both.” It seems quite clear from that phrase “μήτε ἄγγελον μήτε πνεῦμα” that the concept of resurrection described here is, like Paul’s, that of an exchange of the “animated” or “psychical” body of this life for the sort of bodily existence proper to a “spirit” or an “angel.”

Admittedly, some older translations rendered this passage incorrectly, as saying that the Sadducees believed neither in the resurrection, nor in spirits, nor in angels, but that is obviously not what the Greek means. Neither, however, does it say what Wright’s translation quite inexcusably gives us: “The Sadducees deny that there is any resurrection, or any intermediate state of ‘angel’ or ‘spirit.’” That is about as flagrant an act of eisegetical presumptuousness as one is likely to come across in any translation; clearly this is not at all what the original says, or anything it could possibly be taken as implying. Nor am I convinced that Wright really in his heart believes that this is what Luke’s language means, or that he is unaware that he is willfully impressing an alien concept upon the text in order to make it better align with the “reanimation” model of resurrection that he has invented for the first century. The passage plainly has nothing whatever to do with any idea of some intermediate state between death and resurrection; it is the resurrection itself that is described as the assumption of an angelic or spiritual condition.

Consider also Mark 12:25, Matthew 22:30, and Luke 20:35-36, all of which tell us that, for those who share in the resurrection, there is neither marrying nor being married—after all, there will no longer be either birth or (so notes Luke) death—because those who are raised will be “as the angels in heaven,” or “in the heavens,” and will in fact be “the angel’s equals” (ἰσάγγελοι). It is difficult not to think that here Jesus may be telling the Sadducees that the theology of resurrection that he shares with the Pharisees entails no notion of a revived animated material body; it asserts, rather, that the raised will live forever in an angelic manner, an angelic frame.

Nowhere in scripture, of course, is this fundamental opposition between flesh and spirit given fuller theological (and mystical) treatment than in John’s gospel; and nowhere else is the promise that the saved will escape from a carnal into a spiritual condition more explicitly or repeatedly issued. The Logos of John’s gospel does, of course, “become flesh” and “tabernacle” among his creatures, but this involves no particular affirmation of the goodness of fleshly life; the Logos descends to us that we might ascend with him, and in so doing, presumably, shed the flesh. This is the entire soteriological morphology of the gospel, after all: the tale of the descent from above of the Father’s only Son of the Father—the Son who has come down from heaven and who can, therefore, go up to heaven again (3:13)—so that those who are born from above, of water and spirit, can see the Kingdom of God (3:3-5); τὸ γεγεννημένον ἐκ τῆς σαρκὸς σάρξ ἐστιν, καὶ τὸ γεγεννημένον ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος πνεῦμά ἐστιν, “that which is born of flesh is flesh, and that which born of the spirit is spirit” (3:6).

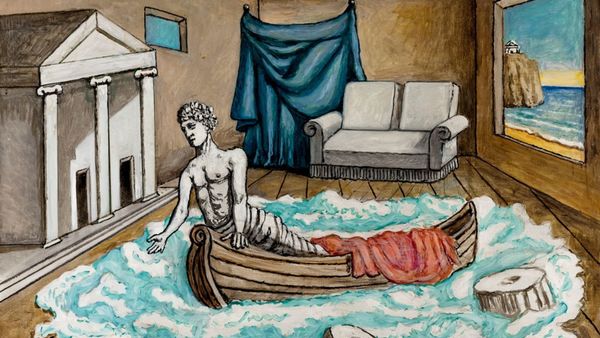

At the same time, of course, no other gospel places greater emphasis upon the physical substantiality of the body of the risen Christ—Thomas invited to place his hands in Christ’s wounds, the disciples invited to share a breakfast of fish with him beside the Sea of Tiberias—but even this is perfectly compatible with Paul’s language. It is, as I say, extraordinarily difficult for modern persons to free their imaginations from the essentially Cartesian prejudice that material bodies must by definition be more substantial, more concrete, more capable of generating physical effects than anything that might be denominated as “soul” or “spirit” or “intellect” could be. Again, however, for the peoples of late Graeco-Roman antiquity, it made perfect sense to think of spiritual reality as more substantial, powerful, and resourceful than any animal body could ever be. Nothing of which a mortal, corruptible, “psychical” body is capable would have been thought to lie beyond the powers of an immortal, incorruptible, wholly spiritual being. It was this evanescent life, lived in a frail and perishable animal frame, that was regarded as the poorer, feebler, more ghostly of the two conditions; spiritual existence was something immeasurably mightier, more robust, more joyous, more plentifully alive. And this definitely seems to be the picture provided by the gospels in general. The risen Christ, possessed of a spiritual body, could eat and drink, could be felt, could break bread between his hands; but he could also appear and disappear at will, unimpeded by walls or locked doors, or could become unrecognizable to those who had known him before his death, or could even ascend from the earth and pass through the incorruptible heavens where only spiritual beings may venture.

And then there is 1 Peter 3:18-19: ὅτι καὶ Χριστὸς ἅπαξ περὶ ἁμαρτιῶν ἔπαθεν, δίκαιος ὑπὲρ ἀδίκων, ἵνα ὑμᾶς προσαγάγῃ τῷ θεῷ θανατωθεὶς μὲν σαρκί, ζῳοποιηθεὶς δὲ πνεύματι· ἐν ᾧ καὶ τοῖς ἐν φυλακῇ πνεύμασιν πορευθεὶς ἐκήρυξεν, “For the Anointed also suffered, once and for all, a just man on behalf of the unjust, so that he might lead you to God, being put to death in flesh and yet being made alive in spirit, whereby he also journeyed and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison.” This verse is extremely easy to overlook, or at least to misunderstand. It is usually read as relating the same story found in 1 Peter 4:6, which seems to tell of Christ evangelizing the dead in Hades so that, though they had been judged “in flesh” according to human beings, they might live “in spirit” according to God. While that verse too is germane to my remarks here, the verses from chapter three do not refer to the same episode. For one thing, whether or not the evangelization of Hades was understood as having occurred during the interval between Christ’s death and his resurrection, the tale cited in chapter three is explicitly about something Christ accomplished after his resurrection. The parallel construction “θανατωθεὶς μὲν σαρκί, ζῳοποιηθεὶς δὲ πνεύματι” employs two modal datives—in or by or as flesh, in or by or as spirit—to indicate the manner or condition, first, of Christ’s death and, second, of his being made alive again, while the conjunctive formula ἐν ᾧ seems to make it clear that, by being raised “as spirit,” Christ was made capable of entering into spiritual realms, and so of traveling to the “spirits in prison.”

Again, the word “spirits” was a common way of designating rational creatures who by their nature do not possess psychical bodies of perishable flesh. And the specific reference in this verse is not to the “souls” of human beings who have died, but to those wicked spirits—those angels or daemonic beings—imprisoned in Tartarus until the day of judgment (mentioned also in 2 Peter 2:4-5 and Jude 1:6) whose stories are told in 1 Enoch and Jubilees. It may even be of some significance here that these infuriatingly enigmatic verses seem to echo the account of Enoch’s visit to the abode of these spirits in order to proclaim God’s condemnation upon them (1 Enoch 12-15). Who can say? It is certainly of considerable significance, however, that this passage seems to say that the risen Christ was able to make his journey to those hidden regions precisely because he was no longer hindered by a carnal frame, but instead now possessed the boundless liberty of spirit.