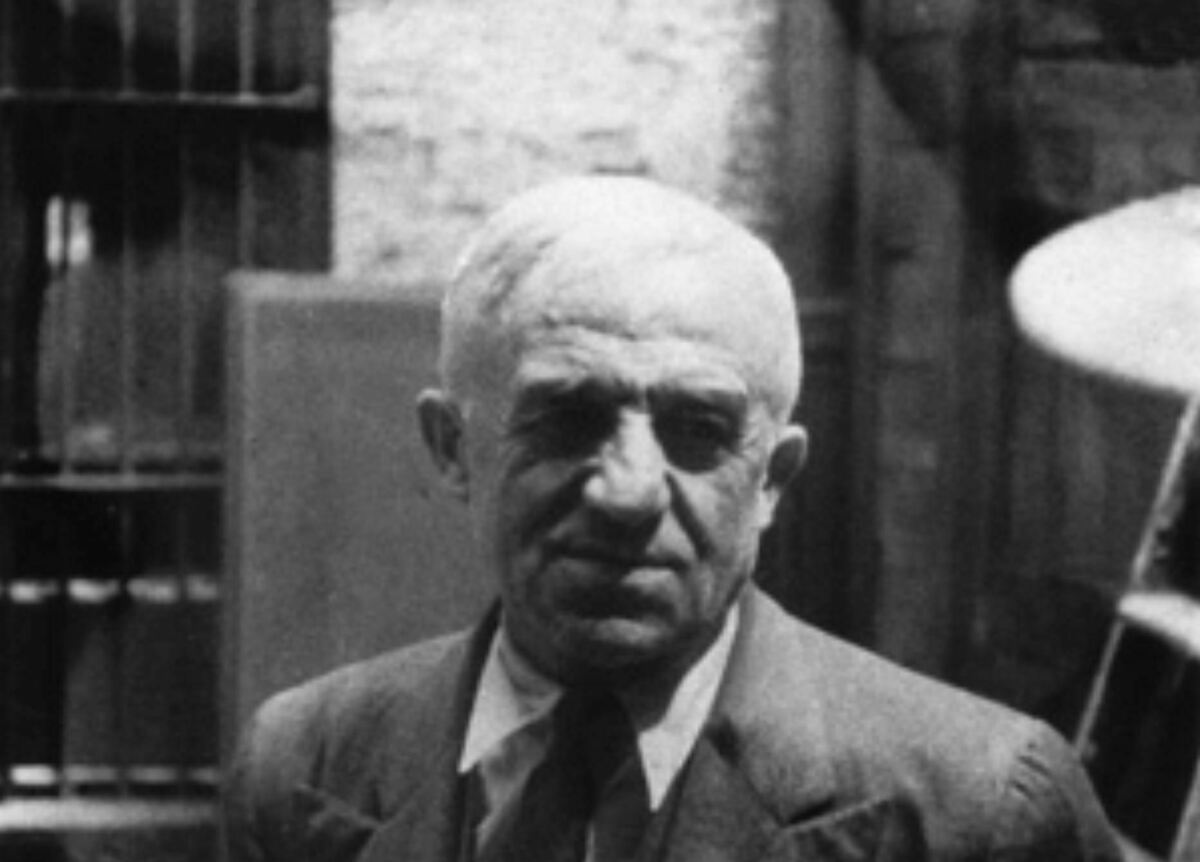

When Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day founded the Catholic Worker Movement in 1933, Maurin’s vision was for (1) hospitality houses, (2) cooperative farming, and (3) community discussions for the clarification of thought on social and religious matters. These did have the “objectives” of giving the poor food and shelter, sustainable work on the land, and teaching the faith. But, just as important as these, they created a new sort of community “in which it is easier to be good.” People joined the movement in droves, because they found there a compelling way of life with other people, different from the rest of the world. There were likeminded, and sometimes not so likeminded, people to befriend, meals to serve, prayers to say, Mass to go to, dishes to do, gardens to plant, alms to give, rides to give, doctor visits to accompany, errands to run, and hilarious stories to tell and retell. It gave you a purpose, a community, an identity, in a world increasingly without any of that. And, perhaps most compellingly, as one of my Catholic Worker friends aptly put it, it is just so much damn fun. This inner life of the community was part of Peter’s genius, often missed.

And so my contention here is that Catholics today are faced with what Catholic Worker Larry Chapp has dubbed the Maurin Mandate: we simply must find new ways of embedding the Gospel in, or rather, of allowing the Gospel to be, the social fabric of real local communities, or face the real possibility of not being able to practice the Faith at all. That is why it is a mandate and not an “option.” My claim is that, for all the variation that is possible and desirable (not everyone has to start a hospitality house or a farm, much less call themselves a Catholic Worker), I think that, after trial and error, faithful Catholics today will find something like Peter’s program the path they end up walking. In other words, the Gospel being what it is, and our society being what it is, intentional Catholic living will tend to take similar forms: liturgy, lay leadership, small community, local living, hospitality, simplicity, friendship with the poor, and a critical, Catholic analysis of our culture.

Why do I think the world is so inhospitable to Catholics today? There are many reasons, but one of the most concerning is the way various forces break up society, including the body of Christ, and isolate us. In one way, this is the opposite of what you would expect me to say, because we are now connected in more digital and material ways than ever before. On the other hand, we are more lonely and depressed than ever. Yet this paradox makes perfect sense in a culture that for a long time has valued freedom and self-determination above all else. We have surrounded ourselves with structures which make it very hard to have genuine relationships. Every new gadget, law, insurance policy or medical advance—and these are the sorts of things we really pride ourselves on these days—is supposed to make us more free to live life on our own terms.

We love technology, politics, scientific institutions, and insurance, because they advance our quest to be as independent as possible. So, pretty soon, after a million cultural changes with this intention, it is no surprise that we do not need other people anymore. I wanted a life I could do by myself, and I got it. I am alone. When I do need others, I can buy them, preferring the impersonal and contractual, because in a way it preserves my independence. One stranger will do my laundry, another will take care of my kids, a third will drive me around. Even my friends I can “manage” online. So, what remains between us endless are bureaucratic rules, mediated by screens and money. That is the social fabric.

The economic aspect of all of this also has a role in splintering us. The motor driving the advance of technology is the market’s free functioning by the law of supply and demand, and this is supposed to mean more freedom for all of us. The theory is that everyone should be unrestricted, to get as much as one can, and (so goes the story) this competition of everyone against everyone ironically makes winners of us all. So, the rules, screens, money and insurance that make up the social fabric are animated by what one economic philosopher called the war of all against all. Accordingly, we are all raised to see others as potential dangers—the competition. It is a war, after all. So, we are positively encouraged to take an impersonal attitude towards economic transactions. “It’s just business, don’t take it personally.” But what if most of life is economic transaction? Then one thing at least will be for sure, it won’t be personal: most of our relationships are now nothing more than one bank accounting with another.

Almost all of us are now so immersed in this culture of fragmentation and isolation that we do not see how profoundly at-odds it is with the life held out by the Church. And that contrast is exactly what Maurin and the Catholic Worker offer. The Catholic life for Maurin consists in what you might call sacramentally formed local networks of an alternative way of life. He just assumed that is what Christianity is. I am not talking about anything too unusual—there are a hundred different examples of it, from St Paul’s house churches to the towns that grew up around the Benedictines, to the medieval parish-based village, to Franciscan “third orders,” and even some attempts at modern “intentional community.”

None of them have ever been perfect and they all have their problems, sin and evil, but the deep logic of all of them is a Eucharistic mode of life: a community that is one body in ordinary things because we are one body in extraordinary things. Or rather: the Church just always is one body, and we ought not make a strong distinction between the practice of what we do at Mass and what we do in “real life.”

Christian life, in other words, is what Maurin called “communitarian”—where that word names an arrangement opposite of our culture of fragmentation. The much mis-used example of the early Christian “love feast” still illustrates this well. After the Mass itself a meal is served where all are welcome and all things are shared and no one deserves anything—life is an economy of grace—because the Eucharist defines our whole life. We are all always beggars (that’s what we do at Mass) and so a life that includes the poor and houses of hospitality are just the logical extension of Christ’s own hospitality to us. Catholic life is a sacramental economy, an economy of gifts, in contrast to the economy of money. Maurin called for little Catholic communities of go-givers rather than go-getters.

In these communities the notion of the common good is central. Our culture defines the common good as whatever allows more people to do, and especially buy, whatever they want for themselves. But if the common good is really just doing whatever each individual wants, it is clear that is no kind of common good at all. The Catholic Worker’s common good, by contrast, takes its logic from the Eucharist, which means that just as none of us gets the body of Christ without the action of the other worshipers, so in all of life we cannot be Church at all, the body of Christ, without each other.

Since, then, every action in a community should be for the common good, community members’ acts are all, in a way, liturgical acts. If all of life is liturgical, that hard line between Christ’s body that is the people and the one that is on the altar begins to break down. We start to see what St. Augustine could have meant when he pointed to the consecrated host on the altar and said “this is the sacrifice of God and us—what we are” (Sermon 227). That is Catholic communitarianism in a nutshell.

And that is what the Catholic Worker seeks to realize in daily practice. Maurin’s genius was to divine out of the Mass, the prayers of the Church, the Scriptures, the lives of the Saints and the message of the popes a particular form of life both traditionally Catholic and especially adapted to (post-)industrial America. His three-point program both flowed from the liturgy and was meant to expand to include all of life in that liturgical orbit. He called this “cult, culture, and cultivation.” The logic of cult, in this use meaning the Church’s liturgy, flows out into everyday life and creates Christian culture.

For example, people have to make the bread and wine for Eucharist, and to prepare community meals. This kind of work is good work, as opposed to many of our fragmenting employments, because it directly supports the best work, the Mass. Not all work is equal, and we can evaluate it, Maurin thought, by these sorts of Catholic criteria. And any good culture will have to include the cultivation of the soil, to draw from the ground what we form with our hands to give back to God, who gave it all in the first place. The vision was very practical: to create a new economy of life that was not divorced from the economy of grace.

The hospitality houses, in particular, have become hallmarks of the Catholic Worker movement. All houses are different, and, sadly, many have strayed from Maurin’s robustly and faithfully Catholic vision, often in the direction of secular political concerns. But let me give as an example one house I have experienced, so you can get the flavor.

The day begins in the house’s small chapel at 6:30am with Mass, said by the priest who lives at the house. A handful of formerly homeless folks and not formerly homeless folks that live there, and occasionally neighbors, join. After Mass some part of that group wanders up the road to the parish church for Morning Prayer, joined by still others—again on a demographic spectrum. Then there is breakfast for all in the rectory, and most go off to their own day, and a few to run errands that came up during breakfast—a ride to the social security office or to get a bus ticket. At 5:30pm some of these same folks and some others are back at church for Evening Prayer, and then to the hospitality house for open dinner, a talk by a local priest, and some semi-coherent conversation about God. Maybe 20 people total that night. At 9:00 the bell rings for Compline, after which most go to their own or shared rooms, one or two on a couch, and one guy is mad that he cannot stay.

That is just one incarnation of Maurin’s vision—and it is a pretty full one. But it was not as intense as it can seem looking at it all at once. Rarely did anyone do all of those things, much less all in one day. People opted in and out as they were able, and based on interest. Some people did not care about the Christianity part, but liked the idea of serving the poor; some the other way around, and lots in the middle. And many Catholic Worker houses have bits and pieces of these things scattered throughout the week. The point is that these are the sorts of offerings that can bring Catholics together in a Catholic way, both because it is simply good to pray and eat together, and because beginning to rub shoulders on a regular basis with other members of the body of Christ, with whatever baby steps we can manage, is not an optional, but an essential, part of being a Christian.

So, as flexible as Maurin’s program is, what is unchanging is that being Catholic is not something that can be either boiled down to a few dogmas and regulations nor summed up in an abstraction like “what would Jesus do?” His idea is that being pulled into the traditions of the Church, even if it is just going to Mass, commits us to a lot more than we sometimes think, including the serious attempt to do what Jesus said and did. Put differently, the liturgy was to be lived all day every day, by finding its application in real flesh and blood small communities. Christian ethics was not a matter, in other words, of taking some account of Christ, alongside a bunch of other “natural” considerations, such as what is “possible” in our times, what is “practical” to make a Christian society, what is “prudential” to plan for the future, or “sensible” to keep us safe.

While certainly making allowance for circumstances such as family life, Maurin saw that sometimes these sorts of “common sense” reservations can just be a refusal to accept the radical nature of the Gospel. Prospective calculations will always leave us in doubt and fear. It is only in starting to live a super-natural life that we find out what is really possible. That is when divine transformations happen.

For Maurin the demands of the Gospel were practical and concrete. All are called to pursue the high path of holiness. Certainly, this included personal piety. Both Maurin and Day were loyal, orthodox Catholics, daily Mass-goers, and spent hours a day in prayer. They thought it is essential to give oneself to frequent prayers and fasting and spiritual reading and holy friendships and frequent confession and regular attendance at Mass. And it is precisely this piety, especially in an industrial society such as ours, that calls us, with very few exceptions, to the daily practice of the works of mercy, to caring for the poor at a personal sacrifice, giving to those who beg, taking no thought for tomorrow, giving up superfluous possessions, turning the other cheek, not resisting the evil doer, forgiving offences, and all the other words of Jesus that are usually neatly filed away under the “hard sayings” that we cannot be expected to take literally and that are left for the priests and monks.

Yet, long before Vatican II, Maurin thought all this was for all Christians in a way that we now call the “universal call to holiness.” “The Catholic Worker,” Maurin wrote, “is taking monasticism out of the monasteries. The Counsels of the Gospel are for everybody, not only for monks. The Counsels of the Gospel are for everybody and if everybody tried to live up to it we would bring order out of chaos and Chesterton would not have said that Christianity has not been tried.”[1]

And yet, for all this high idealism, a further and essential part of the genius of the Catholic Worker, and you’ll miss a lot if you miss this, is the sense that there has to be a deep humor and gentleness suffusing everything we do. The bar is high, but we are not. Laughter and silly stories and failure are the norm. “Judge not” should always be on everyone’s lips. We have to live and preach and pray hard, because Jesus is real, and we have to be merciful and jovial and infinitely indulgent with our neighbors and ourselves. Because, you might say, the counsels of perfection are not counsels of perfection.

This way of life is compelling simply because the Gospel is true. Yet it is also the case that only these sorts of communities will be able to resist the fragmentation we have mentioned. And this is precisely why Maurin called such attention to the “communitarian” aspect of his program. For that fragmentation is only resistible by communities that have their own sort of centripetal force in the form of a real common good. And this begins to be realized whenever small groups of people recognize shared goals, projects, or “goods” internal to the life of the community.

For those who stick with each other, over time, by a messy process that might best be described as trial and error, they begin to determine not only what their shared goods are but how lesser goods are going to be related to higher ones and also how leadership will work. And this community formation is inseparable from the moral formation of each individual, since each must discover how his own desires must be transformed in order to accord with the common good.

Such communities are schools in virtue, in other words, and arguably today just about the only possible ones. Virtue is the ability to put yourself aside for the sake of something higher: for the community and for finding God through it. Yet such schools are vanishingly rare today, not least because of the role played in our lives by consumerism and the market. For once the market is in town, when there is nothing between you and it, after a while you can become concerned only with how to get the best deal—common goods are replaced by whatever thing or experience you desire. Then the goods we look to are no longer internal to a small community, binding it together, but “out there”, wherever the best offer is. And when this happens, neither virtue, nor community are possible.

Not virtue, because the only desire that counts is yours; not community, because community means, as the name suggests, a common-unity, and you cannot have a common-unity of self-pleasers. The market, in other words, feeds on and chews up small and traditional communities, and then spits them out in a thousand pieces. So, it is funny that sometimes being pro-capitalism is associated with being conservative. It seems to me there is nothing more revolutionary than the constant advance of the market to the “next new thing”: whatever’s cheaper, faster, shinier. Such novelty is what sells, what drives the market, and what makes it next to impossible for traditional communities to survive. There is nothing conservative about the market. It is the permanent revolution.

Thus, communitarianism is the only way for Catholics to resist fragmentation because it forces us to put ourselves aside and get on with the business of cultivating virtue, of becoming saints. This is what Maurin meant by creating a “society in which it is easier to be good.” Yet, the development of virtue is never a matter of making cookie-cutter saints. As should be obvious by now, it is so much more than following a set of rules. The invitation to join oneself for a time by a sturdy commitment to a life of holy friendships is precisely to join an adventure in finding the best version of you and the best version of your friends by discovering how your best versions must all include the others. That is the common good.

That is also how Christian transformation works, and it is the only way it works. You cannot do it by yourself, and yet it makes you more yourself. Any seasoned Catholic Worker will be happy to tell you stories about the unique people formed by their own community’s common good. Ironically, then, Catholic communitarianism tends to produce more persuasive characters than the dominant culture that insists that only you determine who you are. The latter generates predictable characters stamped out by Walmart and cellphones, the former a rich variety only explicable by divine creativity, blending the rainbow of virtues and graces.

Maurin thought that this way of life really was capable of renewing society. Or better, it was the only thing that could renew it, because it was just a call for the Church to be what the Church should be today. And if these small groups of Catholics believed their paltry and localized efforts were the path forward for the world, it was not because they expected the rest of America to suddenly jump on board.

But that is exactly why the Catholic Worker vision is more practical and realistic than many politically oriented attempts to “take back America for God,” or whatever. In Maurin’s program, you do not have to wait for the politicians or the voters to line up behind you to stand at the heart of what God is doing to renew our country. For the divine way of renewal is exactly what it was in Apostolic times: small groups of Catholics giving their lives for the Gospel. And the Gospel both refuses to separate the spiritual and the material (Maurin thought that was the great heresy of modern times) and refuses to grab at the halls of worldly power. It is a Church, in other words, that tries to take every atom of life captive for Christ, but refuses to do so by any means other than the “pure means” of the Gospel.

On this basis stands my contention that the path to the future for any Church that is living will look something like Maurin’s vision. It is a mandate for the whole Church because what makes it different is simply what makes the Christian different from the rest of the world. These differences are the weapons of the Spirit: prayer, poverty, community, sacraments, sacrifice, and humility. The weapons we have been trusting for a long time, on the other hand, are simply carnal: cultural hegemony, electoral politics, wealth, insurance policies, and military might. The problem, of course, is not that these weapons are too strong for the meek and mild Christian, but that they are too weak to bring Christ to the world.

[1] See Maurin’s “Easy Essay”, “Counsels of the Gospel”, 211 in Lincoln Rice, ed., The Forgotten Radical Peter Maurin: Easy Essays from the Catholic Worker (New York: Fordham, 2020). This work is now the best and most complete collection of Maurin’s writings.