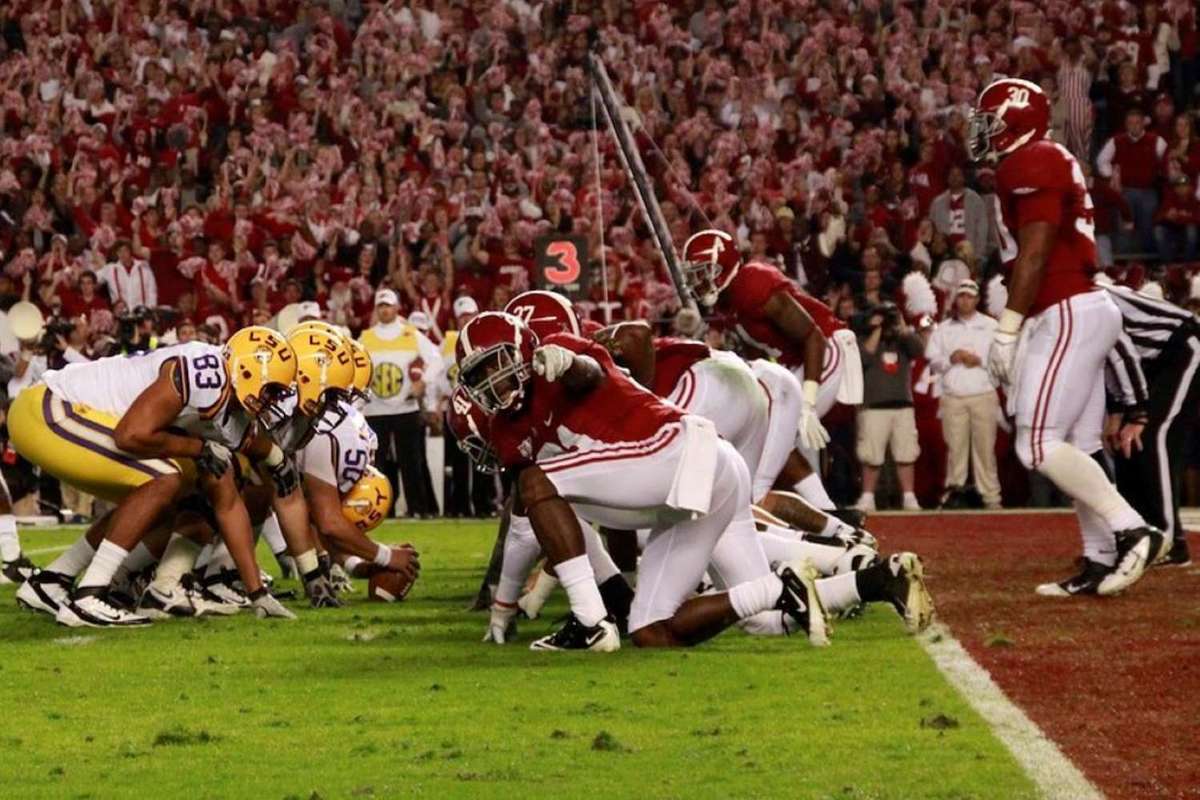

Peter Leithart recently penned the essay, “The Violent Liturgy of Alabama football,” and, as a life-long, die-hard LSU fan and alumnus, I cannot stand idly by while Alabama football and Coach Nick Saban receive undeserved (or deserved) praise. Throughout the course of his essay, Leithart describes an Alabama football program that has obtained a purity that would be the envy of the Cathars and Albigensians, that has a you-can-do-it attitude that every Pelagian would applaud, and that has become a quasi-religious phenomenon on par with Christianity itself, which every good secular liberal would commend.

While it is undeniably true that Nick Saban has created a college football dynasty spanning over an entire decade, it is much less clear that Saban has created a college football program that is theologically praiseworthy, at least insofar as Leithart has described it. It is also equally unclear whether the virtues that Leithart extols in Alabama football are actually virtues at all or whether Coach Saban, as a good Catholic, should be extolled for the so-called “violent liturgy” that he has created in Tuscaloosa. Allow me, then, to paint a more theologically accurate picture of Alabama football before offering some concluding reflections on the nature and purpose of football games and play.

Coach Saban, according to Leithart, is a religious leader, a catechist, and a liturgist who has created a culture in the Alabama football program that “ultimately reflects his Catholic convictions.” He instructs his players in football orthodoxy and orthopraxis, and he presides over a liturgical ensemble of football drills and practices. This, combined with Saban’s proselytization (I mean, recruitment) of high-end football talent, makes for a year-in-year-out, College Football Playoff contender.

Leithart’s praise for Saban is rooted in the latter’s ability to transform Alabama football into a quasi-religious cult wherein individual players are subsumed into the corporate identity of the team. “Ego is the original sin,” writes Leithart, “Early on, Saban hung a sign outside the locker room that read, ‘Out of Yourself and Into the Team.’” As a people who have been brought into this covenant, the players are subjected to the Law and are carefully watched over by a jealous and angry god—and, here, I have Coach Saban in mind—who scrupulously penalizes current players for the venial sin of dress-code violations and subjects his followers to a harsh regiment of works-righteousness.

In the eyes of many Alabama fans and college football enthusiasts, the Crimson Tide are considered the cream of the crop of both the SEC and the Power 5 conferences. But sadly, this is done under the pretenses of an erroneous ecclesiology. For such people, Alabama is to be praised because, unlike the Bayou Bengals across the Mississippi, they compete at the highest level, year in and year out. (This despite the fact that LSU played one of the greatest seasons in college football history in 2019 and had to field what was, for all intents and purposes, an entirely new team in 2020). This makes Leithart ask:

Saban has won 88 percent of his games, a 166-23 record, with five national titles. How does it keep happening? Why doesn’t Alabama collapse every now and then? How do you build a program where a two-loss season feels catastrophic?

But, to measure the overall success of a sports program by wins, losses, and championships alone is too short sighted and too consequentialist. And furthermore, this perspective betrays an ecclesial triumphalism wherein success is equated with worldly power, prestige, and ascendancy rather than fidelity to a suffering God, whose exemplary rejection by the world is the model for our own lives. This ecclesial triumphalism should be left in the pre-Vatican II past where it belongs! And what is one to make of Nick Saban’s “catechesis”? Leithart describes it in the following way:

Focus your energy and mind on what you control, every minute of every day. Learn to find satisfaction in preparation—in conditioning, practice, academics; learn to delight in the nuts and bolts of execution. Don’t dream of holding up a trophy, don’t listen to puffy press coverage; do everything right, and the outcome will take care of itself.

According to Leithart, these spiritual practices are based on the Serenity Prayer, which is typically phrased as “God grant me the Serenity to accept the things I cannot change, Courage to change the things I can, and Wisdom to know the difference.” While this prayer can be interpreted in a Christian manner, it can also promote a dangerous Stoicism and religious activism.

For example, while the Serenity Prayer can be interpreted as simply expressing a recognition of God’s universal providence and the vocation to surrender in love and trust to that which God is asking of us at any given moment, it could also be interpreted as manifesting a defeatist attitude wherein one’s time and energy is only invested in that which is within one’s ability to make some concrete difference. And in those things that one cannot affect any change, it encourages the minimization or elimination of suffering by recognizing that, well, “It is what it is,” and so I might as well try to disassociate my desires from it.

However, as Christians, we should not seek to simply eliminate suffering by resigning ourselves to the current state of affairs, nor is the purpose of life to simply affect change and minimize misery. Rather, we proclaim along with St. Paul that “If I must boast, I will boast of the things that show my weakness” (2 Cor 11:30), and we rejoice in our sufferings, for in our suffering flesh we “complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the Church” (Col 1:24).

By instructing his players to focus solely on what they are capable of controlling by their own natural powers and changing for the better, Coach Saban and Alabama football fall prey to what Pope Leo XIII identifies in Testum Benevolentiae Nostrae (1899) as a twin error of Americanism: the exaltation of natural to supernatural virtue and of activity and activism to the detriment of such things as prayer, worship, and sacrifice. As Leo XIII says:

It is not easy to understand how persons possessed of Christian wisdom can either prefer natural to supernatural virtues or attribute to them a greater efficacy and fruitfulness. Can it be that nature conjoined with grace is weaker than when left to herself?

Ultimately, is Coach Saban’s no-nonsense approach to preparation and to life, his, so-called “Serenity Prayer,” an authentically Catholic mentality? Consider, for example, the authoritative insight of St. Augustine, who in On Christian Doctrine, outlines the following principles:

There are some things, then, which are to be enjoyed (Latin: frui), others which are to be used (Latin: uti), others still which are to be enjoyed and used. Those things which are objects of enjoyment make us happy. Those things which are objects of use assist, and (so to speak) support us in our efforts after happiness, so that we can attain the things that make us happy and rest in them . . . For to enjoy a thing is to rest with satisfaction in it for its own sake. To use, on the other hand, is to employ whatever means are at one's disposal to obtain what one desires.

What Augustine is articulating here are sound Christian principles grounded in both the Old and New Testaments. The end for which we are created is God’s life and love and the rest of the things in this valley of tears are a means to that end, and so we are to love and enjoy God and use the rest of Creation wisely (except for persons, who, as images of God, are ends in themselves).

Alabama football players, though, are told to love and focus solely on the process, enjoy the means, and think not of the end for which the preparation and practice exists. Not only is the object of this congregation’s desire not to be spoken of, but it ought not to even be imagined! Alabama football mistakes the means for the end and use for enjoyment, and in so doing violates the classical axioms St. Augustine laid down for all subsequent theology.

There is more than meets the eye of Alabama’s fumbling of the use/enjoyment distinction. Football, as a game, is a form of play. As a form of play, it is that which should be done for its own sake, that is, it should be done for the love and enjoyment of the game itself because it is a good, and a fortunate side-effect is that one becomes happy and filled with life as a result. Of course, one can and should glorify God through one’s play, and one can even play the game for the sake of God, thanking him in the process for the gift of life and the game. But, if the ultimate reason for playing the game is to win, then one should make an end of the means so as to perfect the skills required to win on gameday, which is the true—though unspoken—end, lest the thought of winning distract from one’s preparation and chance of winning (The rest is a noble lie).

Thus, the Alabama football program, in its despairing pursuit to win, loses the game in the process! What this football program requires is the recovery of the contemplative dimension of the game for both its players and its fans. This is, ironically, best found in the experience of suffering and defeat, which is a phenomenon with which Alabama football has become relatively unfamiliar (Sigh!). Perhaps Alabama football and its fans could experience the necessary conversion of heart and mind by taking the losses that they do experience in stride and, instead of lamenting them, give thanks to God for burning their football idol and purifying their exclusive desire to win rather than enjoy the game for what it is. Why not start with the 46-41 loss to LSU in 2019, or the 9-6 loss to LSU in 2011, or maybe even today against Notre Dame (carpe diem!)?

Near the end of the essay, Leithart speaks of the “moral aim” of Alabama football. This he describes as the development of the right kind of character, which is bigger than football itself:

Saban is often regarded as a one-dimensional football madman, obsessed with winning. To some degree, he’s earned the reputation by his intensity and relentless work habits. The full truth, though, is nearly the opposite. Saban is successful because he aims to produce men, not merely football players.

This intention might seem like a redeeming quality of Alabama football, but it too suffers from the activism mentioned above, lacking a contemplative demeanor and a transcendent focus. The great irony of Leithart’s essay is that the Alabama football “liturgy” is no liturgy at all because it has lost its identity as a transcendent good. The only goods spoken of in his essay are either all too immanent or mere means or both. Where there is no transcendent good, there is no liturgy.

Finally, Leithart describes Saban’s moral theology as a form of Pelagianism that simultaneously recognizes the fallenness of human nature and its inherent limitations. “Pursue perfection;” writes Leithart of Saban’s process,

You can’t achieve it, but that means you can pursue perfection again, and fail again, in the next practice or game or season . . . Pursuing and not reaching perfection applies to football because it’s what life is all about. The only failure is to give up the pursuit.

What Leithart describes here is not a Christian understanding of work and vocation but a Stoicism that betrays a Protestant work ethic rather than a truly Catholic ethos.

According to Saban, the power to do good is inside of you; you just have to choose it and “develop thoughts, habits, and priorities to make good decisions.” But, you can never obtain the perfection for which you strive, and so all that you can do is to choose the good so as to be perfect, fail, and then try all over again. Jesus does command his disciples to “be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matt 5:48), and no one is perfect so all must continually try and try again, but it is Catholic doctrine that God always provides the requisite grace to do the good that he asks and requires of us. And so, even though God does not provide the grace to all to be great football players, he certainly does not demand anything from his people that is impossible, unlike Leithart’s Saban.

Many football fans prefer college football over the NFL because they see in the college players and gameday experience a true love of the game, even though the quality of play is inferior to professional football (Perhaps LSU’s 2019 team could beat the 2020 New York Jets, but we’ll never know on this side of heaven). Sure, the players on both sides of the ball want to win, but they want to win because they love playing the game, love taking the field together as a team, and love representing their school, its fans, and their families. Most college players will never see the turf of a NFL stadium except as fans in the stands, but that does not matter to them when they step on their college field.

Most college football players simply love and enjoy the game and allow their play to be offered up as a fitting sacrifice in a weekly liturgy of football “worship,” wherein players and fans alike adore neither the unattainable pursuit of perfection, nor the formation of a successful character, nor the Goddess of Victory, but the God of Creation through their participation in a natural good for which he is the Primary Cause. Perhaps for many players and fans this is done implicitly and unconsciously (or perhaps not), but it is done nonetheless when they participate in the transcendent experience of a football game and walk away after the final whistle and the singing of their alma mater with an abiding sense of gratitude for and enjoyment of the created order.

This, admittedly, is not a specifically Catholic liturgy, but it is a type of natural liturgy that issues forth from a natural religiosity within a fundamentally good created order. And, because the God of Redemption is the God of Creation who reveals himself in all that is good, true, and beautiful, this liturgy is capable of pointing towards authentic transcendence and being taken up and into the true liturgy where Jesus Christ presides as the Lamb who was slain. Geaux Buckeyes!