SAM ROCHA: I want to talk very specifically about anti-Black white supremacy. I believe that discussions of racism need to be focused on anti-Black white supremacy in this historical moment in America, but I would love to hear if you feel this is an appropriate place to start.

GLORIA PURVIS: Oh yes. It is absolutely a good place to start because we never really hear these discussions framed in that way, having us absolutely at the heart of it. This is specifically anti-Black white supremacy that, frankly, from the time that people in this country decided that Black people should be property, that was the very beginning of anti-Black white supremacy and we’re still dealing with that sin today.

SR: When I think about the problem of anti-Black white supremacy in the Church, my mind goes to Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois famously writes, “The problem of the 20th century will be the problem of the color line.” I think Du Bois was right. Unfortunately, that problem has outlasted the century he predicted it for. How would you describe the problem of the color line, in relation to anti-Black white supremacy in the Catholic Church today, in the American Catholic Church?

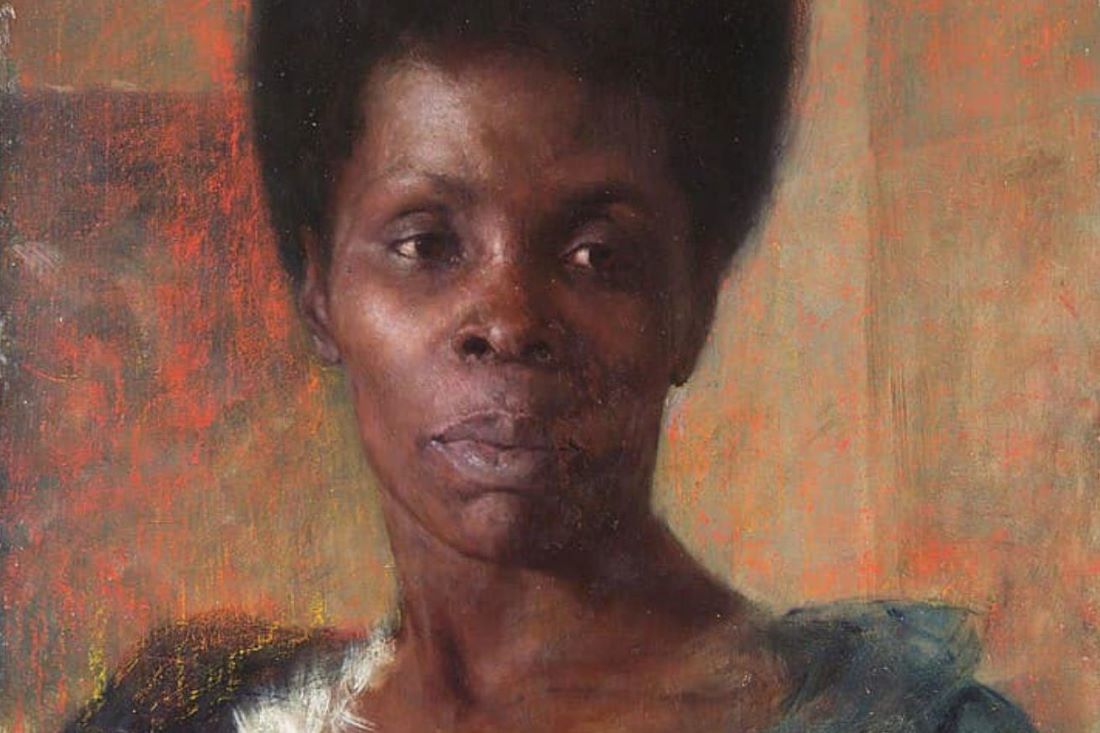

GP: I think of Du Bois’s “Souls of White Folk,” actually, in Darkwater, when he basically says, well, you get this idea that to be white is to own everything. I mean, I’m summarizing how he talks about it but that’s unfortunately what you see in the Church. And people will say things like “Christ can be portrayed in any number of ways,” but the fact is in the majority of the churches, anywhere you walk into in the United States, the only way that you see Christ portrayed is as a white European. I’m not complaining about that, but they have to understand that that does send a message back, particularly when people have tried to have images of Christ that reflect the community. I find, particularly whenever there is a Black image of Christ, for some reason, there’s this call for historical accuracy, whereas you don’t get that with, for example, the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. A friend of mine walked in and she says, “look at that, they have a Beach Barbie Ken Christ.” I’d never thought of it that way and now that she has said that to me, that’s all I see when I walk in there. But, in any event, I still know that it’s Jesus that’s represented, but it also makes it clear for some people that that is the only way He can be represented. And I think it does a disservice to the Church being a Church for everybody, being universal.

I even see that sometimes with Our Lady of Guadalupe; I saw an image, several images, of Our Lady of Guadalupe that were so whitewashed that I was like what is it about dark skin that bothers people? What is it about dark skin that just cannot be seen as good? I remember having a conversation with a priest. He was talking about sin. He says, you know, “the black soul.” And I just joked with him; I said, “Father, why does it gotta be Black?” It sort of caught him off guard. And I said, you know, I understood what you’re saying, but language does convey certain things, particularly in our culture where Black is automatically villainous, bad, evil. And that does go with how people perceive, I hate to say it, Black people. And I see that problem of the color line happening in the Church because of the social conditioning outside the Church that people have experienced. It comes in and informs how they celebrate liturgy, what’s considered reverent, what’s considered holy, what holiness and reverence will look like, and things that we might bring to the table as Black people has to be whitened, if you will, instead of us being allowed to come as our authentic Black selves.

I remember Pope Paul VI saying something along the lines of Black people, bring your gift of Blackness to the Church. If only all the people would see it as a gift. If people could only see this as a gift instead of as something that we need to Christianize and by “Christianize” they mean Europeanize. And that’s a problem. I remember I was helping out a girlfriend of mine that was doing RCIA at another church and she was teaching the class with a very nice young white man and he was telling her that some of the names of the people that were coming into the church, we needed to give them Christian names. She was like, well, what do you mean? And he was saying they were at a disadvantage because of their names. Their names weren’t like David, they were things that he might find, he found, too problematic. And she said, well, they might be the first St. Jalipa or whatever it is, you know; what’s wrong with these names he thought were a little too peculiar? She challenged him on it and I thought, that’s another problem too: They can’t see that what we bring might even inform or could be saintly. These kinds of things are a problem and I think Du Bois was a genius, actually, he even talked about the psychological wage of whiteness that poor whites hold.

SR: I love that you brought up “The Souls of White Folk” because he has this really amazing insight at the very beginning where he says something like: because I am Black, I have to know you, white folk. I have to know you intimately. I know everything about you and you can’t even see me. That’s a theme that comes to me through Black literature including Ellison’s Invisible Man and many, many others. The Black imagination has this sense that the darker brother or sister is able to see the white person in a way that they can’t even see themselves. That psychological insight for me is really powerful.

It’s also important to me that in “The Souls of White Folk” Du Bois is very ecumenical about Blackness. He casts it across color: Asian identity, Indigenous identity, Latin Americans and so on. It’s really kind of fascinating the way he’s conceiving it. I think this psychological account that Du Bois supplies is sometimes really threatening to the majority culture of whiteness in the US. But I do feel that there’s something important about the way in which those who are forced to see this performance of identity, a performance that is almost unconscious for the people for whom that’s just the water they’re swimming in, this does give a certain insight into the human condition. But I wonder: Does it give us any religious, theological, or devotional insight?

GP: I was thinking about what Du Bois says: “My poor, un-white thing! Weep not nor rage. I know, too well, that the curse of God lies heavy on you. Why? That is not for me to say, but be brave! Do your work in your lowly sphere, praying the good Lord that into heaven above, where all is love, you may, one day, be born white!” So heavy. And it automatically puts us on a level of not being equal, which implies not really being made in the image and likeness of God as white people must definitely be. You know what I mean? And so, when you start there, what kind of deprogramming, what kind of exorcism of the mind has to happen?

Because I do believe that this is definitely a lie the devil has placed in our culture and in the minds of people. And it also deprived them of the ability to understand that Black people can teach them some things about God as well. I think that’s one of the things that James Cone talks about. They cannot comprehend that they could learn anything about God from Black people, which again, I think, deprives. They’re operating in a state of deprivation. They can’t even hear the voice of the Lord because it’s coming from over there. Not to say that Black people are lepers, but in the minds of some people, we are that. People love St. Francis hugging the leper, but how much did they miss God, the presence of God, the voice of God, because He comes from a place of something that they, unfortunately, because of social conditioning, interiorly loathe or fear or look down upon or cannot comprehend that it can be good, beautiful, and true because it comes from that, them, over there.

So, religion-wise, I think we have a bit of a psychological exorcism that needs to be done because of the conditioning and the lies from the devil that are pervasive in our culture. I mean, it has to be pervasive in our culture if you can look at a human person and deny their humanity and say that they’re a slave and then, after they are free, to work intentionally to make sure they do not receive the equal treatment and rights they’re supposed to receive, not only just under the constitution and the laws of the state, but also according to the teachings of our own Christian faith.

SR: When you bring up the historical fact of enslavement, here’s something that worries me: On the one hand, we have the story of Exodus, which is this powerful story of liberation. It’s a story that people have for millennia associated with whenever they find themselves under oppression. But, at the same time, there’s an indigenous scholar, Eve Tuck, who says, “decolonization is not a metaphor,” and I sometimes worry about that. Chattel Slavery is not a metaphor. It actually and really happened. And 246 years of that with 100 years of Jim Crow on top of that is not just some kind of symbolic source of meaning. This is real. And we can’t just confront it under exclusively mythic terms.

At the same time, I’m also inspired by things like Cone’s idea of The Cross and the Lynching Tree and the way in which these powerful sets of religious meanings are set into the experience of oppression. I don’t know if my concern registers with you at all, but maybe you could help me think about it or deal with it a little bit. Because I do think the story of Exodus is powerful, but I also don’t want to lose the concreteness of this anti-Black white supremacy we’re talking about, especially as it relates to Chattel Slavery.

GP: So, I’m just looking at “The Soul of White Folk,” and right before what I read earlier, he writes, “This assumption that of all the hues of God whiteness alone is inherently and obviously better than brownness or tan leads to curious acts;” curious acts, “even the sweeter souls of the dominant world as they discourse with me on weather, weal, and woe are continually playing above their actual words an obligation of tune and tone, saying: My poor, un-white thing!” So as I think about anti-Black white supremacy and I think about what you’re saying about Chattel slavery, I guess I keep thinking that sometimes the enslaved here psychologically are the white people, cause they can’t break those chains of supremacy, their souls are in handcuffs, if you will, and are unable to see who we are and the beauty of us, what we deserve justly. They can’t see the beauty of us and let’s be clear: To break those golden chains is going to take some pain on their part.

Too often people don’t want to deal with the ugly reality of white supremacy . . . anti-Black white supremacy. Because what does that say about yourself when you look in the mirror and you see how it has conditioned you. Sometimes people get caught up in their own guilt and their own feelings. I want to say, “Look, it ain’t about you, set yourself free.” They can’t liberate themselves in the sense of thinking about things without trying to get permission from a Black person. You’ve got this. You might make mistakes. Sam, as I think about it, I also think there’s a counternarrative that’s also being continually plugged into white America: This idea that they are really the oppressed ones who are under attack just because people are asking, or demanding at this point, what they are due. Our call for justice being perceived as an oppression of white folks is a problem too. Because then it makes it have to be either or when all we’re saying is that there’s enough for all of us. But I am not sure I am addressing your point on Chattel Slavery.

SR: No, I think you’ve flipped right into that. It’s not only the historical conditions, it’s also the psychology of the oppression, the way in which whiteness oppresses white people as a kind of slavery. I think you’re right. And I think it challenges me to continue to be more creative. Speaking of creativity, one point you brought up raises another touchy subject. In Carter G. Woodson’s Mis-Education of the Negro, he actually pins a lot of the blame for this kind of psychological whitewashing on the Black church. He is fairly secular. I see him as a proto Ta Nehisi Coates or something. What has always struck me are two things.

One, at least from my American point of view, tends to think of the Black church as the AME or the Black Protestant church, yet I feel (and this is something by the way that I’m not doing; I mean, I literally make this association myself, so I’m not just like blaming and pointing) . . . I think that the beauty of Blackness in America has to be a sense of the Black church that is far more ecumenical than only the AME, which is not to say that the Evangelical, Pentecostal, and Holiness traditions don’t have something really unique to offer from themselves, but then, on the other hand, when I read Woodson talking about the mental enslavement that comes through the Church, I, as a person who’s niether Black nor Protestant, I sometimes nod my head a bit like, “Yeah, that happens.” That’s pretty convicting for me. And I think that sometimes it’s seen as unfaithful to admit it, but the fact that we can admit to it means that we have to a conversation about it. So those are two slightly different angles, but I wonder what you think about them.

GP: Malcolm X even had a critique of those things. I remember reading, and I can’t remember who wrote this, but a Black priest said that he was walking down the street and he ran into Malcolm X and they had a brief conversation and when Malcolm X found out that he was in the seminary to be a Catholic priest, he was like, have you lost your mind, or something to that effect, because there’s this idea that within Christianity as Black people, at least as practiced in the United States, you have to leave something of your Blackness at the door; you’re taught that any anger, righteous anger that you have, that you’re not to act on it. And I think that’s a big misrepresentation of anger.

I remember the case of Botham Jean, where a police officer burst into his apartment in Texas and killed him while he was eating ice cream. The Catholic media was just in love with his brother hugging Amber Guyger, the police officer that killed Botham Jean. And I was reading a lot of Black media at the time and people were outraged. They were saying “That’s the only way you want to see Black people always accepting brutality from white people and never standing up for themselves.” A lot of people blamed Christianity, because they didn’t see in Christianity a way for Black people to express a righteous anger, to be motivated by anger for justice. And I would say that that’s a misreading of Christianity.

Thomas Aquinas talks about how anger, rightfully experienced, moves one to justice. But yet, somehow, the only thing that gets promoted, amongst the Black community is that the Christlike thing to do is to not be angry, to swallow it, to be meek abused people, who are always ready to be abused and walked on. And I would say that is not at all the Christian message. And, in fact, it is because of our Christian faith that we have every right to demand justice. We have every right to express our anger. It is because of our Christian faith, when we understand and embrace how beautiful we are, that we are made in his image and likeness, that we should not accept anything less. But at that time, there was what we now call “respectability politics.”

You’ve got to look respectable to white people and that includes how you worship, how you dress, how you talk, the God that you worship. You don’t want to be a threat to white people. You don’t want to frighten them. And, again, I think operating in that space doesn’t allow us to operate as free full human beings, made in the image and likeness of God, to have agency and a full range of emotions. You see that tension when people think of the Black church, particularly people who are outside of the Christian tradition, and even some of us in it, and get the sense that we must be all okie-dokie, that we’re not allowed to be angry or express emotion because it’s not considered reverent, it’s not considered holy. I think about the Church Fathers having fist fights! I think of that. It is almost a fear of a Black rage that would be unchecked.

And I think to myself: If we have not burned this country down by now, what makes you think we’re going to? That’s another sign of God’s grace on my people, in our heart. Our reaction to these gross injustices isn’t to then exert the same gross injustice on the people that did this to us. We may be angry, and we may march, and we may even cause some civil disobedience, but we’ve never gone out and said, we’re going to just have widespread killing of white people; indiscriminate, widespread killing of white people. It’s always been, let’s come to the table and these are our demands, and this is what we want, because we have inherent dignity. So, I can see the tension that Woodson was talking about, but at the same time, I also say that if we really understand our faith, we see that this anger, this righteous anger, absolutely should be propelling us to seek justice. There is nothing wrong with that.

I’m tired of people telling me, I can’t express this righteous anger. Even when people look at the current protests: They want to say that it is evil, that you do this and that. This is a rage people are expressing. That this is their outlet. Now I’m not trying to justify destruction or anything like that. I understand where the rage is coming from and where the anger for justice is coming from. And sometimes I believe they think, “Oh, white community, this is what you care about? Profit and money? Well we’re going to burn down all those things you care about. You don’t like that? Then don’t kill us. What we value is our life.”

SR: I think about the plagues. Everybody compares the protests to Jesus flipping tables in the temple, but I was like, no, wrong analogy. Whenever Moses went to Pharaoh and said, “let my people go,” when Pharaoh didn’t pay attention to him, God destroyed everything he loved, he destroyed his first-born son until he obeyed. And then whenever he tried to go back on the deal and chase these people down, God drowned him in the sea. I guess now I’m doing what I said earlier that I didn’t like, which is the more symbolic and metaphorical way of seeing it.

GP: No, do it. It speaks to me. I love it. Please do that. These are the things that make us think. Even when you come to the symbolic, it gives us something to meditate on and maybe it’ll give them a way to see what they consider Black rage. It is a rage for justice. It’s a righteous anger. It’s interesting, I really wonder: Without these uprising, would we still be having a national conversation on racial justice? Would you and I even be coming together to talk about anti-Black white supremacy and really trying to address the problem?

Then I think about how this anti-Black white supremacy functions on the psyche of Black folks. Sometimes we have to tell ourselves, remind ourselves, “no, don’t make yourself small so people can feel big; be who you are,” realizing there’s a price to it. Realizing there’s a price to it.

SR: This is where some of the social mantras are interesting. I don’t know if it was Stokely Carmichael’s expression, but the Black Power movement, the anthem of Black Power, I found that really expressive of something really deep. And I think that empowerment narrative spread to a lot of other people, even people who weren’t Black at the time. With this sense of empowerment came the Black is Beautiful mantra. I just loved that because it was such an affirmation of what you said earlier, from the Pope, about the gift of Blackness, it brought this expressive side. Today the anthem is Black Lives Matter. I fully say it in the spirit of the time, and I think it needs to be said over and over.

But when I think about it in contrast to Black is Beautiful and Black Power, it almost sounds to me like there’s an undertone of “look, y’all aren’t getting it. You didn’t get it. You’ve missed this so many times, so we’re going to make it basic for you: Black Lives Matter.” What do you hear in those anthems?

GP: Black Power. Oh man. That was before my time but coming up and reading about it and seeing it, it just made so much sense to me. When I saw the natural hair, people weren’t straightening their hair to be respectful. It’s just your full on, unapologetic, beautiful Blackness. They proclaimed Black Power speaking against society’s intentional oppression of Black people, the intentional deprivation of rights. And they responded with Black Power. I think of the Panthers standing, exercising their second amendment rights. We are going to defend ourselves. We are going to protect ourselves, our families, all of that against an oppressive structure that comes in and abuses and kills our community. And it was such a frightening thing for people in the US and the US government as well.

But what that says to me is there was and is the understanding that despite the lies about us, how we’re represented in movies, books, advertisements, cartoons, even the exclusion of our achievements from the history books, we know that we have power. We have self-determination despite being told we can’t go past this spot; we can achieve and do. And, in the places where you’re going to try to exert brutality against us to keep us from achieving, we are going to defend ourselves. We will not allow you to destroy the beauty that is us. And to say the words Black is Beautiful is to counterwitness to the lie that it isn’t. Almost the same thing that you see in “The Souls of White Folk.” Saying it openly, Black is Beautiful.

It’s amazing that it would be considered a political, revolutionary phrase. Because it’s just the simple truth. Black is Beautiful. A small story on that: When I was in Orlando, Florida, the bishops had a big meeting down there, one of the speakers on the panel that I was moderating said “Black is Beautiful” and he had everybody repeat it after him. He then said, “I bet for some of you, that’s the first time you’ve ever said it.” After that panel, I was talking with a man from India, of Indian descent, and this white gentleman comes over to us. He was just so angry that people said Black is Beautiful. I mean, just really angry. We were looking at him kind of puzzled. And he was saying, you know, “everything is beautiful” and so on, and this Indian brother dropped some knowledge on him that was so beautiful.

He said, “yes, that may be true, but it is too often that Black has been denigrated as not beautiful. And the fact that you’re having this negative reaction to saying it just makes my point.” So here we are now with Black Lives Matter. You’ve got this truth and yet too often, to divert from that truth, people will talk about the ideology of the organization. Why do you do that? Why do you deflect and try to drill down into the ideology of three women that founded an organization of that name? Why is it that they have to obsess on that instead of trying to use all their energy and say, yes, that is true? And how can I make that more of a reality? The energy spent on trying to say what’s wrong with this, what’s wrong with that, is an intentional thing, in my opinion, to make sure we don’t do the work to try and make it a reality. It is as if the mantra Black Lives Matter, the movement that uses that rallying cry and the organization, are a greater evil than the evils of police brutality and murder that the movement is trying to fight. The racial justice movement is a movement to defend and protect the life and dignity of the oppressed.

SR: I’ve often wondered, would you rather it be Black deaths matter? Do you want it to be more graphic? I think Black Lives Matter is a generous anthem because it allows us, in some ways to like Black is Beautiful and Black Power, to affirm Blackness; it doesn’t make harsh demands for us to focus on.

For instance, the fact that Black people are being murdered and killed perniciously with no recourse to justice or to any kind of the civil entitlements that every other person should have because of basic moral laws and principles. In Black Lives Matter, you get to affirm Black life. You could say, and this is my slight critique, that this mantra functions at the expense of forgetting this is actually about Black death.

GP: It’s about Black death and, honestly, a right to a natural death. We talk about a right to life from conception to natural death. Well, don’t we have a right to a natural death? Our death shouldn’t be hastened by the violent acts of the state that is supposed to protect us. We talk about a right to life. We have a right to life. We also have a right to a natural death. And I don’t know if we ever think of it in those terms. I have a right to a natural death; I have a right to live until God decides that this is the end of my time. But when the state acts in a way that deprives me of that right that is a gross injustice as well. We see that in the brutalization of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

I keep thinking of poor Tamir Rice, twelve years old, in a park, playing with a toy gun and the police get a call and instead of seeing a child with a gun and maybe a moment’s hesitation, he’s killed by the police officer. But then again, there’s that conditioning of the fear of Blackness: That Blackness can only be criminal. That Blackness is not innocent. And that psychological wage where you can see a white child and see innocence and youth and “oh, that can’t, that can’t necessarily be a gun;” that hesitation, that benefit given to a white child that isn’t given to Black children. And it’s because of this anti-Black white supremacy that has conditioned people in our country for centuries.

SR: It’s so powerful to think about the right to a natural death in this context, because it also shows how some people may see their moral project as trying to promote human flourishing, but, in many cases, in certain communities, it’s not “let me have a flourishing and happy life,” but just “let me die in peace and with some dignity.”

GP: Yes, yes.

SR: I mean that’s heavy. That’s heavy.

GP: I think about that because someone’s like, “Oh, you know, we talked about from conception to natural death, but a violent death isn’t a natural death so should we change it?” But we do have a right to a natural death. Just as we have a right to life, we have a right to a natural death. And I think that has implications. When we start to think of things in that manner, that has implications for how we view a lot of things. I think as Christian believers, and particularly from the lens of race, if we were to see that not only was George Floyd’s life was taken from him, but his right to a natural death was taken from him as well. That should also move us to want justice.

But again, anti-Black white supremacy comes into play here as well. And what I mean by this, Sam, is why is police brutality, being able to talk about it, such a problem? Why do people have to say stuff like, “well, back in Georgia, police are good.” But we’re not talking about that are we? We’re talking about specific behavior and practices used against the Black community that are not morally acceptable.

I’ve come to a place where I’m realizing that some people think that this kind of brutality on our communities is necessary for peace because there is something they see as animalistic and uncontrollable in our community. It’s something that they fear. And it’s also the lies they’ve been told about criminality in the Black community and all these kinds of things which started way back, even just after slavery. I remember reading in Slavery by Another Name that they created these Pig Laws and whatnot so that it was illegal if you were unemployed, but they only applied it to Black people. That made Black criminality and arrests go through the roof not because we were more criminal but because the law was intentionally created with the intention of creating a new slavery for Black people.

On the face of it, they didn’t say it was only to be applied against Black people, so it looked racially neutral, but in effect it was only applied against Black people. And so you have all these reports and newspapers at the time about the explosion of criminality of Blacks and how we were not fit to be free and, see, look, look, we have the statistical evidence of criminality, but the intention was to enslaved people again and send people to these plantations, steel mines, all those kinds of things for capital, you know, for money. And they benefited from it. So, this lie of our criminality right after our freedom, that was intentional for other purposes and has stayed with us to this day. If you look at the greatest number of people that kill white people it is other white people, but, somehow, we are the threats to white peace and life. It’s just another lie. It’s just another lie to put that on people that affects how they’re able to perceive police brutality against Black people, when the underlying assumption is that we must be doing something wrong, it must have been something criminal.

SR: One place where you can see that fairly directly is also in the Church. I grew up in the Texas Hill Country. In that region, the Catholic Church is racially divided between mainly European immigrants, Polish and German, and Mexican Americans. One of the things that always struck me, especially as I thought about it in retrospect, was that at the sign of peace, I could shake everyone’s hand, but there were families that I knew would never let me take their daughter’s hand in marriage because I was Mexican-American. It goes without saying, by the way, that the question of marrying a Black person for them would have been in some cases even more out of the question.

Getting back to the question of life, what does it mean to gather together at a church yet know that we are not willing to gather together as a Church? Because to me you can’t be a Church whenever you will not, at least in potential, see yourselves as potentially bonded together through the sacraments in every way possible, which would include marriage.

GP: Amen. Well, you know, you’re touching on something here. Again, this is anti-Black white supremacy from its earliest stages, this myth of the Black buck and this insatiable sexuality always desiring white women when the reality was it was Black women who were being raped and brutalized by white men. And so, this idea that is still with us today, this animality to Black sexuality that just can’t grasp that we could be fit for marriage, as marriageable.

When that happens, you’re right: It completely goes against what we believe as Catholics. Because race is not a precondition for marriage. It’s just simply not. I had a priest tell me about a family that came to him. They were like “our daughter, a white girl, has been dating a Black man and we’ve done all we can to break them up. So, we need your help to break them up; we need you to talk to them because we know you understand,” and he’s looking at them like, no. And they were just shocked. Even in dating, you know, people wouldn’t even consider it.

I’ve looked at some of these Catholic dating groups. If I were a single young Black woman, I would not in any way, shape, or form feel like I’d be considered a mate or somebody who someone would date even though we have so much in common in a shared faith. But that’s just a nonstarter; race comes in there. This is a history I think we don’t talk about in our country. I’m like “we didn’t all come over here looking different colors like Vanessa Williams.” We didn’t just magically end up looking this way; the definite rape and abuse of Black women didn’t end with slavery. At the Dark End of the Street, by professor Danielle McGuire, talks about the Civil Rights Movement being animated by rapes of Black women like Recy Taylor, who I think Oprah made famous by talking about her case. And do you know who the NAACP’s number one investigator was for these abuses against Black women? Rosa Parks.

She wasn’t just meek and quiet. She was a bad mamajama, okay? She collected all these stories and the NAACP and all these Black people were trying to seek justice for these women, which you simply couldn’t get. Rapes also happened by white police against Black women. So, part of the movement was animated by these women wanting to move about freely and not be assaulted and accosted sexually by white men. And that’s a hush-hush part of the movement but it’s true. And, again, I think because we don’t have these frank discussions about the abuses against Black people in the area of sex, we are not undoing these myths. And, also, there’s a myth of outstanding white behavior and purity. The record just doesn’t bear it out.

When you look at what happened in slavery and after, we have some coming to grips to come to in the country. I mean, even with our founding father Thomas Jefferson, people want to say his “relationship” with Sally Hemmings. It was rape of a teenage girl! We can’t talk about these things because it undoes the myths that we tell ourselves about, frankly, white supremacy.

SR: I want to come to one last topic. It’s one that’s near and dear to my heart and constitutive of this interview. I want to talk a little bit about Black and Brown solidarity. In the context of the United States, of course, Brown has a particular meaning in relation to the Latin American, Latino, Hispanic, whenever you want to call it, they change the names for us every few years, community. (In Canada, I’ve learned, by the way, that Brown is actually a signifier for the South Asian community. So I don’t have access to it here the way I do in the United States.)

One of the most difficult things to come to grips with in my own conscience, specifically in relation to anti-Black white supremacy is this: In my community, we also have experiences of racism that are not experiences of anti-Black white supremacy and one operative way in which anti-Black white supremacy works in my community is by using us, or by us allowing ourselves to be used, as these moderate counterpoints where you get model minority myths and all these kinds of things.

It is well known in the Mexican American community that, by and large, we sat the civil rights movement out because we were white on the census. For us, we often don’t want to join in the struggle against anti-Blackness. We’re so close to being white, why would we stop? You know what I mean? To me, there’s a lot of anti-Black white supremacy that doesn’t necessarily manifest itself through white people, but instead manifests itself through a kind of desire for whiteness, even amongst people of color like myself. The Catholic Church in the US is clearly marked by its Brown population. We are all over the place now in the American Church and have been long before the US even existed. The American church is not going to hide from the need for representation of our people, language, and all these things.

I wonder though, as I think of immigration issues and all those things that I support both culturally and morally, and every other way: I want to make sure that I don’t fall into allowing the centering of some of those issues from my community to be centered in such a way that they secretly, or even implicitly, or maybe even explicitly, are harmful to my Black brothers and sisters in the Church. And so, as you can hear, I’m uncomfortable with this part of the conversation, but we never get down to it because we’re usually just answering really basic questions from white people. I wonder what you think about this.

GP: I’m so glad you brought it up because sometimes I think the Brown community is a shield that some in the Church use to say, “see, I’m not racist because I’ve got all these Brown people,” but they’ve never dealt with their anti-Black white supremacy. I’ve always found it curious that some dioceses will send their seminarians to Mexico to get a diverse experience. Why not send them to the other side of the tracks to the Black community? Why do you need to leave the country, learn another language, to do outreach in the name of diversity? We have so many people of color right now, right here, Black people, in fact, in these dioceses that are largely ignored and not evangelized. Why not send those priests right on over there, let them have a cultural immersion in those communities and serve them?

But again, I think that the safer thing to deal with is to leave the country and deal with people in Mexico who may not have the same historical relationship that Black people have with white people in this country. It’s a fear of having to deal with anger. It’s a fear of having to deal with people being suspicious. Like, what are you about? And it’s a fear of not being the one that’s in control. So, I do sometimes see my Brown brothers and sisters used as the cover. “See, we’re diverse, look at us, we’re not racist” when they’ve never really dealt with what some people call the original sin of this country, which I would call anti-Black white supremacy. Even when Brown people come here there’s something about, “at least you’re not Black.” You know what I mean? You’re one step up the ladder; at least you’re not Black.

SR: I should emphasize, before I get rightfully admonished by my own community, I should recognize that there are Afro-Latin peoples all across Latin America. So, I was being very specific to the Brown side of my community. The forgotten Black side of my community is evidence of how racist and how anti-Black we can be. We will even essentialize Brownness as not having Blackness within it. And the truth is we do, like our Afro-Latin brothers and sisters in Cuba and Puerto Rico, all over, even in Mexico, by the way.

GP: Yes, Mexico has a Black community, so does Colombia. Joe Arroyo’s song “Rebelión,” it’s about a slave woman being struck by the master. It’s a beautiful Spanish song. And you look in Colombia, they have plenty of Afro-Latinos, the Dominican Republic. I actually studied abroad. I went to university there in the Dominican Republic. And I will say, though, there’s an effect of colonialism where some people don’t even want to see themselves as Black. You’ve got them in Cuba, I think the Afro-Latin community is having an awakening in some places. I mean, you have people like Celia Cruz, you know what I mean? She was a Black woman, the beauty within the Hispanic Latino community is that we’re all present there, but it’s also a surprise to me that people from certain countries don’t know that there are Black Latinos.

SR: And then you also have the Sammy Sosa effect, right?

GP: Oh, I feel so bad for Sammy.

SR: My heart breaks for that guy.

GP: He was so beautiful. And now he looks just like, to me, the psychological damage that has been done to him has been made manifest by how he’s just ruined his look. That beautiful Black skin that he had, it’s been ruined; those beautiful Brown eyes, they had everything. This is what anti-Black white supremacy does to the Black person that destroys them if they let it. If they let it. He needed to hear Black is Beautiful. He needed to hear Black Power. He needed representation of Blackness that affirmed him, that showed that what he had was a gift and not a curse to be whitened away. Sammy Sosa, my brother, I just want to hug him and say, “it’s okay baby, you’re beautiful.”

SR: My dad’s an evangelist. The first principle of evangelization, and I think this principle is at the very heart of American evangelicalism going back to the Azusa street revival and all kinds of other things crossing its path, but the basic principle is the love of God; that God loves us. What Black is Beautiful can do is to not simply affirms someone’s sociological or political identity. What it does more radically is it offers them God’s love in the way we experience love, which is by saying “you’re beautiful.” My grandma used to say, “All my children are made of gold” in Spanish, she’d say that all the time. It was her way of telling us that we were all beautiful.

The cornerstone of the proclamation of the good news, of the kerygma of the Gospel, is fundamentally that God loves us personally. And for someone who can’t love themselves, for someone who experiences self-loathing and self-hatred, that is a place where anti-Black white supremacy is not only wrong on all these moral and political levels, it is also a fundamental impediment to understanding the meaning of the love of God and experiencing that love. The injury goes far deeper than civic life; it cuts into our ability to experience Divine love. There is an inverted analogy between city and soul here.

GP: Yes, because if you start to believe that lie, you think you yourself are not lovable, so how could God love me? Then there’s the self-loathing and then the psychological damage and then the acting out in ways that are continually seeking white approval instead of seeking God’s love. We can make an idol of whiteness because you’re seeking that approval. “We’re almost white” instead of saying “I am made in the image and likeness of God and I am beautiful and God loves me; he made me with a purpose and a reason.” To operate from there is to completely reject anti-Black white supremacy. But it also means you have to question a lot of things and really try to think about and analyze why.

Why would I even allow some of these things? But again, if you’re conditioned from an early age, sometimes you don’t see it because it is the water in which we swim, the air which we breathe, but when you have that awakening it’s a liberating thing to say “I am a child of God and I’m a gift.” And what he’s given me is a gift that I will freely share within the Church. Somebody could be listening to this and say, well, she must hate white people or have some animosity toward white people. I do not. And the reason I don’t is because they have been seduced by a lie of the evil one. I pity people trapped in that, where the devil has a foothold in their life. I pity people that can’t see the beauty of my Blackness. I want them to be free to love as God intended and anti Black white supremacy robs some of them of that.

I like to tell people that this is like going into a garden only being able to see one color and size and style of a plant. You want to go in and see a garden bursting with colors and all kinds of things. That’s beautiful. But when it comes to humanity, it has to be monochromatic, boring, only one thing, one way. I think it is just antithetical to God’s desire for the world. So, I don’t want people to hear that and automatically assume. People also hear these things and they get so defensive. Hear and receive this in the mode in which we intended, which is to liberate you to the truth and to say, “we’ve got to deal with the anti-Black white supremacy if we all are going to truly say we want to bring about the kingdom of God.” That’s the work that we are willing to do because we love the Lord.

Believe me, I could just check out and just go and be up in the Black community, the heck with everybody else. I could do that but that’s not what God has asked me to do. I think we have a responsibility as believers to work for the sake of justice for the Black community because we’ve been wronged for so long. And I want to say, also: I’m a joyful Black woman. People are like “Oh, it must be hard.” I am a joyful Black woman. I love my Blackness. I love it. I love our music, our food, our culture, our history of achievement despite opposition. Honestly, we have done so much despite all the intentional opposition against us. That makes me even say, “Oh, how blessed we are by God that we’re still overcoming.” I keep thinking how much more we could achieve if the shackles of anti-Black white supremacy were removed from our society and how much more society would benefit from that.

SR: Amen. You know, the only thing I disagree with Du Bois within his essays is that he sometimes gives the impression that there is an essential whiteness at the center of Christianity. As someone who did his homework on the Early Church, that’s my only point of contention. I want to tell Du Bois that Christianity has been in Africa a lot longer than it’s been white.

GP: Yes.

SR: It’s true. And people don’t even realize that Christianity, demographically speaking, has never had its majority of people in Western Europe, what were called the Oriental churches, always vastly all outnumbered the Western churches. And today Latin America and Africa are where the Church is growing demographically. I think people in the US often see the Pew Reports of the weakening of church attendance and whatnot, but they almost selectively forget the fact that the Church is actually growing and blossoming in other places that just don’t happen to be places where whiteness is a hegemonic cultural force. I even wonder sometimes whether some of the narratives of the Church’s failing despair and cynicism are actually more indicative of their inability to admit that there is an essential core of Christianity that does not necessarily suffer from the perverse allergies of anti-Black white supremacy, that has been, continues, and will continue to grow and be the hope that Christ gave to Peter.

GP: Well, when we look at how the Church is growing in Africa and the Philippines, and places like that, people somehow say that if the Church is dying in Europe then the Church writ large is dead and it isn’t true. It’s just simply not true. But again, Sam, how is that reflected and how is God represented in art in our Church in the United States? By and large, how he’s represented, how Jesus is represented, how the Holy Family is represented, is as if it all came from Europe.

There is a lot of anti-Black white supremacy when you put up these pictures of Christ as an African, a Black man; people are uncomfortable. People automatically say you’re just making this political, now you’re making it political and you’re a Black-identitarian. I’m not doing this to counter anything. I’m doing it because I find it beautiful. And why can’t we meditate on that? And also, most of the Church in the world doesn’t look like the European representations that we have.

SR: I mean, to be generous to Europeans, even Europeans don’t look European. It’s kind of a bad rap that they give themselves whenever they talk this way. A Spaniard, a Frenchman, an Englishman, a German, a Pole, a Nordic person are hardly a monolith.

GP: You’re right. You’re absolutely right. But you know, it’s interesting that you say that because when people come to the States it’s not that you’re German or this and that. Your racial identity is what matters, that your white or how you’re classified as white. And with it come certain benefits, certain privileges. They don’t have the burden of Blackness, that additional burden. And that’s one of the things I talk about sometimes with people. They really hate the term “white privilege.” They say, “I grew up poor.” But you didn’t grow up with that additional burden of having to deal with race in the way that Black people do.

So, when the Black priest shows up, being told “Can we have a real priest?” Those are the kinds of things that people actually say in this day and age when they encounter a Black priest. It’s a sad statement on the social conditioning that doesn’t stop at the door of the Church. It is right all in the Church. What are we to do to deal with that?

Another example of anti-Black white supremacy: I don’t know if you remember this story about the KKK priest out of Virginia. There was a priest who was a member of the KKK in his youth before he entered the priesthood right here in the DC area. He burned crosses on people’s lawns, including Jewish people, and it turns out the Black family whose lawn he burned a Cross on was Catholic. He was charged and had to pay all this stuff back, which he never did. He fled the area, sort of hid his identity. And then came to the Church, was sent off to the North American College in Rome and was in several dioceses and finally ended up in Virginia and, with the Charlottesville murder of Heather Heyer, one of his old students wondered what happened to Father so and so. Because he has always talked about how Robert E. Lee was a saint and all these kinds of lost cause types of things that he was teaching kids who were being homeschooled. And when she saw that he was a Catholic priest in her diocese, she was shocked and she reached out to the diocese. And when his background came out, I thought to myself, how did he make it through seminary? How did he make it through North American College in Rome? How did he make it all this time with those sentiments? Nobody thought it was a red flag? And also, how did he never hear anything in his education to become a priest that made him have a moment of conscience.

That tells me something is missing. Something is missing in grasping and dealing with the very real anti-Black white supremacy that is endemic to this nation. How he could go through all of these things and in no way, shape, or form have a moment of conscience and realize either a) the priesthood was not going to be for him, because he couldn’t separate from his feelings and thoughts, or b) that he needed to actually have a come to Jesus moment and then actually go back and make repairs? He was supposed to pay these people for the damage that he had done to them. And I often thought of the faces of those Black Catholics when they found that he was a priest. What does that do to them? All these things show that we have some gaps and holes missing in our formation of priests, in our preaching and catechesis, and how we talk about the faith. We skip over what must be addressed: To rid ourselves of the stains of anti-Black white supremacy wherever we can in our faith, in the United States.

SR: Amen.

EDITORIAL NOTE: Gloria Purvis is the host of ETWN's Morning Glory. She is an Editor of The African American Catholic Youth Bible. This interview took place via Zoom on July 10, 2020. Our heartfelt thanks go out to Gloria Purvis and Samuel Rocha for all the time, heart, and effort they put into bringing this important conversation to our journal.