Quite a few Christian commentators of all stripes are noting that pandemic-time feels like a yearlong Lent or Advent. They draw the conclusion that we need Easter and Christmas to remind us of God’s love for us and that he will resurrect us, so to speak, from this pandemic. That is all well and good, but the Epiphany is the holiday even more essential, because the response of some Christians to the pandemic has revealed that there are substantial numbers of their co-religionists across all denominations that have not truly learned the lesson of Epiphany.

Many of these Christians respond in fear, not just to COVID, but to God. Instead, Epiphany is a holiday that should relieve us of fear. Our need for the message of Epiphany, the deeper message beyond the revelation of Christ to the Gentiles and other common homily fodder, will become more apparent if we stop to consider more fully what the men from the East really were.

The men are identified as μάγοι, which common English translations often render as “wise men,” “kings,” or “magi.” All three renderings are deficient and they obscure the bold declaration made by the μάγοι’s act of worship. While the men certainly were wise and they may have very well been kings, what the word μάγοι most strongly suggest is that they were Zoroastrian priests who would have also been practitioners of various forms of magic, especially astrology. Sometimes the fact that the magi were astrologers is mentioned in Epiphany sermons, but either from ignorance or a misplaced desire to not scandalize the congregation, the nature of astrology is glossed over.

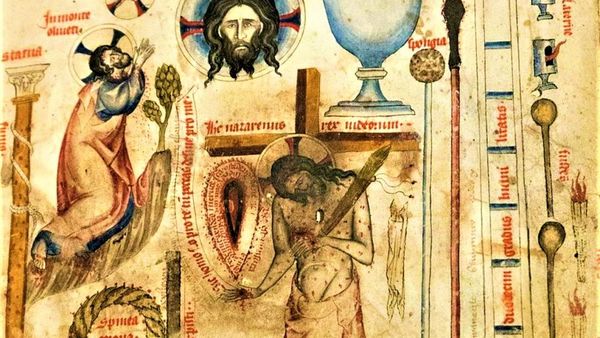

More often than not, the magi are depicted as mostly benign ancient astrologers. However, the purpose of astrology was not simply to mark the passage of time or to satisfy curiosity. The goal of astrology and other magical practices is to, “gain control over the human and the celestial worlds, in order to assure blessed destiny for human beings through wresting control from the hostile evil powers.”[1] The magicians who visited Christ, like all magicians, had made it their life’s work to uncover the various ways they could manipulate some sort of supernatural power to serve their ends.

The fact that magicians came to worship Christ is scandalous because Scripture in both the Old and New Testaments is decidedly anti-magic. In Exodus 22:18 the Israelites are famously instructed, in the words of the KJV, to “not suffer a witch to live” and are given more detailed prohibitions on magic in Deuteronomy 18:10-11. Additionally, some commentators have suggested that the prohibition on taking the Lord’s name in vain was intended to bar the use of the Lord’s name, which he had entrusted to Moses, from being used in incantations.[2] Even the sacrificial system is set up in such a way to be non-magical: the entrails, especially the liver, were to be burned so that they could not be used to practice extispicy and haruspicy.[3]

In the New Testament, it is shown that the control of demons does not come from incantations but from faith (Luke 9). There is also St. Paul’s ministry in Ephesus where, “A number of those who practiced magic collected their books and burned them publicly” after witnessing Paul exorcise a demon in the name of Christ (Acts 19:19). The Lord forbids the use of magic, especially vain attempts to magically manipulate him, yet here in the Gospel of Matthew we celebrate the arrival of a group of magicians who have come to worship the God-Toddler.

Here, Benedict XVI in Spe Salvi (an encyclical that I suggest everyone read and re-read during this time) is helpful for understanding what exactly happened when the magicians knelt before Christ and why it is “good news of great joy for all people,” even today (Luke 2:10). In explaining the biblical basis for hope, the Pope Emeritus explains that at the time of Christ’s first advent:

Myth had lost its credibility; the Roman State religion had become fossilized into simple ceremony which was scrupulously carried out, but by then it was merely “political religion.” Philosophical rationalism had confined the gods within the realm of unreality. The Divine was seen in various ways in cosmic forces, but a God to whom one could pray did not exist. Paul illustrates the essential problem of the religion of that time quite accurately when he contrasts life “according to Christ” with life under the dominion of the “elemental spirits of the universe” (Spe Salvi §5, quoting Col 2:8 in the last line).

As we would say today, the Romans were simply going through the motions in their strange rites. There was no lively faith or hope. There was only fear, and they thought by keeping their rituals, they could appease the gods. They thought that they could “assure blessed destiny” through their rites. In essence, they were practicing a kind of magical religion. However, all of that began to change when the group of Zoroastrian magicians showed up in Bethlehem. Drawing on St. Gregory Nazianzen, Benedict continues:

[Gregory] says that at the very moment when the Magi, guided by the star, adored Christ the new king, astrology came to an end, because the stars were now moving in the orbit determined by Christ. This scene, in fact, overturns the world-view of that time, which in a different way has become fashionable once again today. It is not the elemental spirits of the universe, the laws of matter, which ultimately govern the world and mankind, but a personal God governs the stars, that is, the universe; it is not the laws of matter and of evolution that have the final say, but reason, will, love—a Person.

He concludes from this:

And if we know this Person and he knows us, then truly the inexorable power of material elements no longer has the last word; we are not slaves of the universe and of its laws, we are free. In ancient times, honest enquiring minds were aware of this. Heaven is not empty. Life is not a simple product of laws and the randomness of matter, but within everything and at the same time above everything, there is a personal will, there is a Spirit who in Jesus has revealed himself as Love (Spe Salvi, §5).

The magicians have found the Star that ended astrology. When is revealed to them is that the universe is ordered by a loving Creator with whom nothing can contend; they realize that magic is both ineffectual and pointless. Magic is pointless because it is Love as Dante penned “That moves the sun in heav’n and all the stars,” and in its movements of the sun and the stars grants “peace on earth,” as the multitude of heavenly hosts sang to the shepherds.[4]

All of our feeble attempts to gain dominion over the celestial realm are unnecessary because the celestial realm is ordered to our good since it is through Christ that “God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things.” Magic, or at least magic that seeks to control God, is ineffectual for a number of reasons that cannot be recounted here, but here in Matthew’s account we see that magic is ineffectual because it cannot control the Child by Whom “All things came into being” and in Whom “all things hold together” and in Whom “we live and move and have our being” (John 1:3; Col 1:17; Acts 17:28).

Yet, the lesson of Epiphany is easily forgotten, and as Benedict notes, the way of thinking and seeing the world that was overthrown by Christ’s advent has become popular once more. We may no longer think the stars themselves govern our fates, but it is fashionable in our techno-scientific milieu to speak of the primordial impersonal forces that formed the stars as governing our fates. We do not think of ourselves as magicians, but we deploy a similar kind of thinking when we deploy our techno-scientific apparatus to control and subdue the natural (and sometimes supernatural ) world, a point I have argued elsewhere. The ongoing pandemic has certainly exposed the existence of this kind of thinking, but it is not just the kind of people who preach “Trust Science” that are engaged in this kind of thinking.

One of the sadder revelations of this past year is that many Christians have a magical mindset when it comes to thinking about God and how we ought to worship him. It has been a truly ecumenical affair as Christians the world over have shown that they understand God to be a cruel tyrant who must be worshipped in just the right way with just the right words or else he will punish us, as if COVID was not already an instance of divine wrath.

Indeed, there are clergy from various denominations that go so far as to claim that COVID was sent by God as a punishment for one reason or another. The solution, then, is to use the correct rites and practice them in order to end the pandemic or, if not to end the pandemic, to prove ourselves faithful so that we can be spared whatever other wrath is awaiting us. In either case it is an attempt to use the worship of God to secure our blessed destiny.

Examples abound, so I will only name a few. There was a Protestant fundamentalist acquaintance of mine from high school who posted a list of American cities alongside their COVID case count and what he thought were their besetting sins, which were generally of a sexual nature. The solution, he proposed was for America to turn back to God—as if we ever really faced him as a nation!—so that he may remove the scourge of the disease. As inclined as I am to agree with him that Boston was being punished for being the seat of higher education, what his post revealed is a mentality that sees prayer and worship as transactional and, ultimately, as a means of control. Worship God and he will be good to us. Sacrifice a bull and Baʿal will send us rain.

While a certain subset of fundamentalist and evangelical Protestants grabbed headlines here in the States, in part thanks to figures like John MacArthur, the Eastern Orthodox here and abroad were engaged in their own debates that reflected the same basic magical way of approaching worship, such as the row over the use of multiple communion spoons instead of a common spoon in order to prevent the spread of disease.[5]

Meanwhile, a certain strand of Roman Catholics seemed set on proving correct old Protestant polemics about the magical nature of the Mass. In the spring, the Congregation of Divine Worship, issued a new votive mass they called “Mass in Time of Pandemic.” One popular Catholic clickbait mill published a complaint about the ways that this special Mass differed from the “Votive Mass for the Deliverance from Death in Time of Pestilence” found in the “Traditional Latin Mass”—their tendentious name for the Extraordinary Form. One change they took issue with was that the entrance antiphon for the new votive mass is taken from Isaiah 53:4, “Truly the Lord has borne our infirmities, and he has carried our sorrow,” whereas the older votive mass draws its introit from 2 Kings 24:16, “Be mindful, O Lord, of Thy covenant and say to the destroying Angel: Now hold they hand, and let not the land be made desolate, and destroy not every living soul.”

The attitude expressed in the complaint and in its comment section is one that sees repentance as something done to appease an angry “god,” so that he does not kill us, not as something we do because we are grieved at how we have sinned against an ever-loving God who was born into a poor family and suffered for us. Who suffered, perhaps, with a few respiratory diseases of his own.

This approach to the worship of God is nothing new to the Christian tradition. In fact, it stretches all the way back to our roots in ancient Israel. At one point, the Israelites did a good job of keeping the letter of the ritual law. Yet, according to the prophets the Lord rejected their sacrifices because they had failed to care for the widow, the orphan, and the alien: they had failed to love their neighbors as themselves (E.g. Jer. 7:21-26; Amos 5:21-24). Later, James and John will repeat similar warnings in their epistles. As mentioned above, the disciples also fell prey to magical thinking in their attempts at exorcism. In the early Christian period, magical papyri were created that included the names YWHW and Jesus amongst other Christian theonyms.[6] The magical approach to Christianity has always been with us then, and who amongst us is wholly innocent of ever falling into this way of thinking?

It would be easy to simply mock those who promote this kind of magic, but I cannot—and not simply because I too am guilty. It seems to me that such thinking is not just the result of poor catechesis but a spirit of fear. The world is a scary place as the year just past reminded those of us who are accustomed to living comfortable and complacent lives. COVID is simply the biggest recent reminder of our finitude and the hostility that can arise from nature, especially when we are not good stewards.

Not only is nature scary, but for some (all?) of us, God is scary. We find him scary either because we believe he hates us, or even worse, we think he has abandoned us because of his hiddenness. As Herbert McCabe once preached, “The root of all sin is fear . . . the fear that really, in oneself, one does not matter.”[7] This fearfulness is why I think we need Epiphany now as ever. We think that we do not matter. That God hates us or simply does not care, so we seek a way to make him turn aside his wrath or to make him care.

That is what the “wise men,” “kings,” or “magi” thought they had to do before they saw the Star of Bethlehem. Those ancients, more so than us, knew the world was hostile and scary, and so they turned to magic. Yet, when they came to Bethlehem there they found perfect Love, and “perfect love casts out fear” (1 John 4:18). Love, which is most fully and perfectly revealed to those ancient Persian magicians as a child on Mary’s lap, casts out fear because it, because he, “is strong as death” (Song 8:6). Therefore, St. Paul could write,

I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord (Rom 8:38-39).

Should we still examine ourselves and see what sins we have committed? Is it okay to sometimes wonder if God has abandoned us? Sure, but this COVID-tide Epiphany, I think we should all reflect on how in toppling the ancient attempts at asserting control over earth and heaven, God revealed in the Incarnation that Love rules the universe and this Love is concerned for us. We need not cower, neither before COVID nor before the Lord. Instead, we can fall on our knees and rejoice that he has entered the muck in which we prodigals roll. Rejoice that he is “acquainted with infirmity . . . he has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases…and by his bruises we are healed” (Isa 53:3-5).

[1] Howard Clark Kee, Medicine, Miracle and Magic in New Testament Times (New York: Cambridge, 1986), 99-100.

[2] Yiu-Sing Lucas Chan, The Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes: Biblical Studies and Ethics for Real Life (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012), 56.

[3] John W. Kleinig, Leviticus (Saint Louis: Concordia, 2003), 89.

[4] Dante, Paradiso, Canto XXXIII

Luke 2:14; Col. 1:20

[5] For an overview and introduction to this debate see: Nicholas Dassouras, “From One Spoon to Many,” Public Orthodoxy.

[6] Kee, op. cit., 112.

[7] Herbert McCabe, “Self-Love,” in God, Christ, and Us (New York: Continuum 2003), 70.