Not to put too much pressure on anyone, but after you read a few hundred pages of the Compendium on the New Evangelization and study Pope Francis’ encyclical letter The Joy of the Gospel, it’s hard to escape the conclusion that the popes are expecting us to bring about, with God’s help, a total transformation of culture worldwide. This renewal of all reality is to organically grow out of the personal relationships with Christ of lay disciples who put their faith into action in our vocations of work, family, and community life.

This isn’t to say that the clergy and religious don’t have a role to play. A world evangelization mission requires a laity that is formed in accordance with the Gospel and the Catechism. Thus we will be able to “Observe, Judge, and Act” our way through the myriad situations of our shared lives. That won’t happen without the experience of sacraments and especially the Mass as moments of grace, holiness, and formation.

Consider two of the Americans Pope Francis recommended to us during his speech before the U.S. Congress, both of whom were adult converts to Christ and his Church: Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton. They testify to the importance of liturgy in their formation. While they are considered by many to be saints (Dorothy Day has been elevated to Servant of God and her cause for canonization is underway), and some may say therefore atypical, the truth of that matter is that they were not born saints. Dorothy Day was a drunken libertine radical communist who had an abortion. Thomas Merton fathered a child out of wedlock.

In March of 1966 Dorothy Day wrote in the Catholic Worker newspaper:

The Mass was the center of our lives and indeed I was convinced that the Catholic Worker had come about because I was going to daily Mass, daily receiving Holy Communion and happy though I was, kept sighing out, ‘Lord, what would you have me to do? Lord, here I am.’ . . . To me the Mass . . . is glorious and I feel that though we know we are but dust, at the same time we know too, and most surely through the Mass that we are little less than the angels, that indeed it is now not I but Christ in me worshiping, and in Him I can do all things, though without Him I am nothing. I would not dare write or speak or try to follow the vocation God has given me to work for the poor and for peace, if I did not have this constant reassurance of the Mass, the confidence the Mass gives.[1]

In his 1964 essay “Liturgical Renewal: An Open Approach,” Thomas Merton described a significant moment of his conversion journey, when he found Corpus Christi parish in New York City and began attending Mass in 1938:

One reason why I am a Catholic, a monk and a priest today is that I first went to Mass, and kept going to Mass, in a Church where these things were realized. Corpus Christi Church had the same Roman liturgy as everyone else in 1938. It was just the familiar Mass that is now being radically reformed. There was nothing new or revolutionary about it; only that everything was well done, not out of aestheticism or rubrical obsessiveness, but out of love for God and His truth.

I am a convert too. The first time I wandered into Mass as an adult, in a small mission church in Draper, Utah, I knew that here was something different. It wasn’t a very impressive place. They didn’t have a cry room, and the baby chorus was singing lustily. Music was one guy with a guitar and maybe two singers. But that Advent liturgy touched me.

The sacraments and especially the Mass are where people come face to face with Christ and his Church. Sometimes that is with great faith and devotion, other times it is the twice a year visit at Christmas and Easter, and then there are the skeptics and the unbelievers and the grievously wounded who wander in. Because the Mass is where we meet Christ, the liturgy is critical to the New Evangelization. At my parish, on average about 1600 people walk through our doors for one of our four weekend Masses throughout the year, many more on Christmas and Easter, and at baptisms, weddings, and funerals. Every one of these encounters is an opportunity for evangelization. An evangelization plan without liturgy is missing one of the critical-can’t-be-replaced factors.

Before we enter more deeply into the subject of what we can do, let’s take note of two things we should not do if we want our liturgies to become more evangelical. The most important of the issues to avoid is the temptation to venomously argue about our liturgy. Certainly people will disagree about this, that, or the other regarding liturgy. But if those discussions can’t be carried on in a Christ-like manner, that’s a major problem for evangelization.

In his book, Liturgy and the New Evangelization, Timothy O’Malley comments about this tragedy in the modern Church and quotes Pope Francis:

Thus the constant talk of liturgical reform—whether raised by self-denominating traditionalists or progressives—has become an obstacle to the New Evangelization. These liturgical wars have deformed such prayer into an expression of our own idols, of what the experts want the Church to become: “It always pains me greatly to discover how some Christian communities . . . can tolerate different forms of enmity, divisions, calumny, defamation, vendetta, jealousy, and the desire to impose certain ideas at all costs, even to persecutions which appear as veritable witch hunts.” (Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, §100)[2]

A step towards evangelical liturgies would therefore be a ceasefire in our liturgy wars. That is a real possibility at each local parish intent on evangelization. It may involve some prudence about where we go online when it comes to liturgy, for near occasions of sin abound in the websites where liturgy is discussed in cyberspace. With good will and prayer, local parishes can achieve a liturgical peace that is grounded in the discipleship of those responsible for the liturgy.

A second problem to avoid is disconnecting our liturgy from life, as though we could somehow sit in beautiful and pristine churches and not be concerned about what is going on around us.

O’Malley continues:

As Pope Francis makes clear, the beauty of the liturgy is not complete until it culminates in the liturgy of life . . . Outside of the Catholic imagination, Francis’ social critique is [seen as] a matter of partisan politics . . . [however] Pope Francis’ emphasis on becoming a church of the poor, the powerless . . . is an extension of his Eucharistic and evangelical vision . . . such solidarity requires that the Christian enter into the fullness of history.[3]

The concept of “full and active participation” is therefore much more than ensuring that everybody sings at the right times during Mass. It continues as we walk out the door, into our vocations in work, family, and community life. In the liturgy, we come to understand, as O’Malley puts it, that our existence is “love made flesh.” Thus it comes to pass, as we celebrate Mass with our sisters and brothers, in spirit and in love, over time we become what we eat and drink. That’s evangelization!

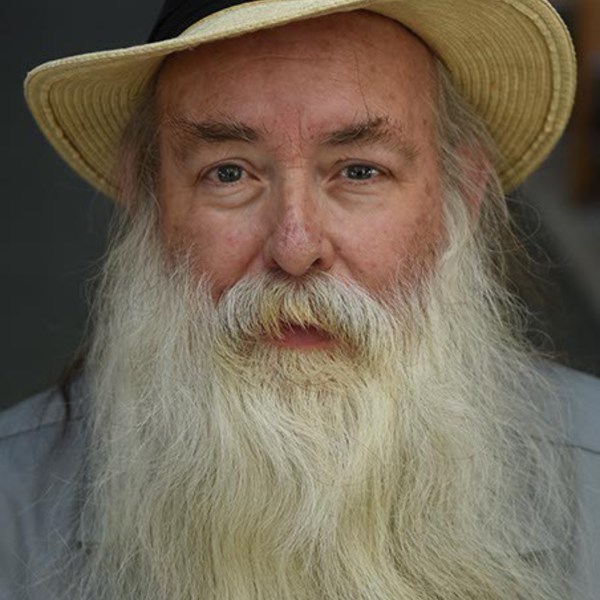

Featured Photo: George Martell/The Pilot Media Group courtesy of Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston; CC-BY-ND-2.0.

[1] Dorothy Day, “The Unwanted” in On Pilgrimage (March 1966), 5.

[2] Timothy O’Malley, Liturgy and the New Evangelization: Practicing the Art of Self-Giving Love (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 2014), 135.

[3] Ibid., 136.