The Japanese word kodokushi roughly translates to “lonely death.” The term might be a touch poetic for what it actually describes, conjuring as it does the romantic image of an individual stoically riding off alone into oblivion. An existential cowboy leaning in his saddle towards the darkening horizon, embodying all the heroic maverick energy that our contemporary world so highly values. The apotheosis of freedom in current Western society being a complete atomization of self, an undoing of all the bonds which constrain us, kodokushi almost sounds like something to aspire to.

The material reality of the “lonely death” is grim. Disgusting, even. It is an odor the neighbors do not notice until it is already too late. It is the kinetic hum of maggots digesting an undiscovered corpse. It is the slow accumulation of “past due” notices in the mail, piling up until a stranger comes to query the “customer” in person and finds their liquefying remains. It is the cagey instinct of the entrepreneurs who have capitalized on kodokushi as a business opportunity, monetizing their lurid and sad deaths by offering special cleaning services for the tiny apartments of elderly folks who have died alone and unnoticed and are well into decomposition. In a phrase, it is the complete thing-ification of people who have outlasted their use-value. It is the fate of people who, as Simeone Weil quoted from The Iliad in a similar context, have become “dearer to the vultures” than their loved ones or community. Kodokushi is the process of humans being reduced to garbage. And it is not unique to Japan. As the first generation of humans “liberated” from kin-connections ages and dies, kodokushi becomes a global phenomenon.

Scholars who study demographic shifts refer to what happened in relatively wealthy, Western countries after the Industrial Revolution—a decline in both death and birth rates—as the First Demographic Transition. You can basically sum it up as the process of large, extended families, shrinking down to the nuclear unit. What is occurring now—the epidemic of loneliness, the severing of deep familial ties, kodokushi, etc.—is known as the Second Demographic Transition (SDT). A recent article in City Journal describes the SDT as something that:

Began emerging in the West after World War II. As societies became richer and goods cheaper and more plentiful, people no longer had to rely on traditional families to afford basic needs like food and shelter. They could look up the Maslovian ladder toward “post-material” goods: self-fulfillment, exotic and erotic experiences, expressive work, education. Values changed to facilitate these goals. People in wealthy countries became more antiauthoritarian, more critical of traditional rules and roles, and more dedicated to individual expression and choice. With the help of the birth-control pill, “non-conventional household formation” (divorce, remarriage, cohabitation, and single parenthood) went from uncommon—for some, even shameful—to mundane. [Belgian demographer] Lesthaeghe predicted that low fertility would also be part of the SDT package, as families grew less central. And low fertility, he suggested, would have thorny repercussions for nation-states: he was one of the first to guess that developed countries would turn to immigrants to restock their aging populations, as native-born young adults found more fulfilling things to do than clean up after babies or cook dinner for sullen adolescents.

An emphasis should be put on the phrase “more fulfilling” in the paragraph above, because along with the technological means to survive without the assistance of a large kin-network comes the shift in values which defines human fulfillment in a manner largely de-contextualized from social ties. Someone of a Hegelian bent might say that this redefinition of human needs made possible the creation of the technology in which to manifest the atomized lifestyle. A Marxist might insist that the chicken always comes before the egg.

Either way, and however far back in the dim memory of the human story you might trace the lineage of the drive to sever connection to and responsibility for one another (we can certainly go back at least to Cain), when taken to its logical conclusion the result always seems to be the same: people are transformed into refuse. In his Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino wrote about Leonia, a city which worships trendiness. Every morning the citizens revel in new songs on the radio, new products delivered to their doors, and brand-new fashions in clothing and food. Of course, the hidden god of Leonia is not necessarily the novel, but the discarded. As Calvino writes,

It is not so much by the things that each day are manufactured, sold, bought, that you can measure Leonia's opulence, but rather by the things that each day are thrown out to make room for the new. So you begin to wonder if Leonia's true passion is really, as they say, the enjoyment of new things, and not, instead, the joy of expelling, discarding, cleansing itself of a recurrent impurity. The fact is that street cleaners are welcomed like angels.

In our new kinless world, where people are discarded the same as refrigerators or sneakers, the folks who dispose of our refuse are also angels of death.

The desire to collapse in on ourselves like dying, solitary stars, might be older than ancient. But more recently we can see it manifest in last centuries various ideological turns against both tradition and, more importantly, the notion of a transcendent reality. The Italian scholar Augusto Del Noce writes in The Age of Secularization that “the two poles that ultimately define all of today’s conflicts are traditionalists versus progressives, and all positive values reside with the progressive cause.” It is this same overly-simple dichotomy in which the student “rebellions” of the 60’s (and those of today, as well) placed themselves. As Carlo Lancellotti, Del Noce’s translator, sums up the situation in the introduction to The Age of Secularization,

The students confused the affluent society in which they had grown up with “tradition,” and thus rejected the very institutions (the family, the church, liberal education) that still resisted the technological mindset. This tragic misunderstanding led them to extremism, that is, to a form of revolutionary utopianism that fails to critique the society of well-being “because it supinely accepts, as fragmentary mush, the ideal principles that started the process that led to the current system, the system it would like to oppose.”

This does not just explain why both the hippies and their contemporary social justice equivalents are so easily co-opted by corporate enterprise, but also why so often the end results of their agitation lead to the exact opposite of what they claimed to be agitating for. The communitarian bliss of the hippie transformed into the individualized aggression and greed of the 80’s and 90’s. The monomaniacal focus on “safety” of the contemporary SJW is not unrelated to ongoing suicide and depression epidemics. This is because, says Del Noce, with some sympathy to their sensitivity to the imperfections of society, progressives have misdiagnosed the causes of suffering and dedicated themselves to working against the very institutions and ideas which not only humanize us, but save us from psychological and spiritual deterioration: the family, the church, the transcendent.

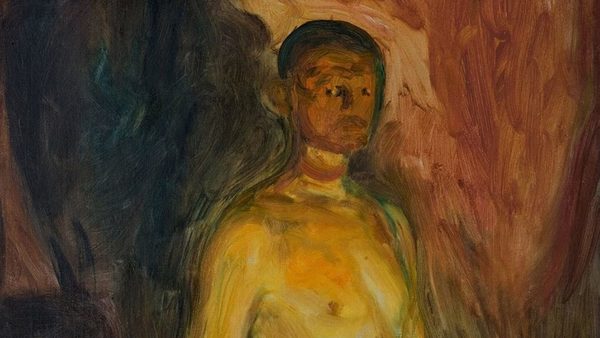

The lonely death is part of the cultural effluvia of this progressive miscalculation. We occasionally get glimpses of it here and there in our art, literature, and music; but often with the same attendant misdirected anger towards the vestiges of institutions which might help to prevent anomie. Any number of contemporary songs or movies come to mind where the family is seen as something to liberate oneself from in order achieve a deeper contentment and truer sense of self. Few examples exist of art which conveys the horror of the isolated individual, imprisoned by solitary desire. French author Michel Houellebecq might be the rare example of an artist who unflinchingly gazes into the abyss of modern self and, with a cold eye, catches sight of all the ways in which constructing a world composed simply of desire sated and desire thwarted contributes to profound human misery. In what might be his most accomplished novel, The Elementary Particles, Houellebecq directly confronts the failures of 60’s radicalism, particularly where it pertains to so-called sexual liberation. A few quotes might better articulate the spirit of the novel than a recounting of its plot:

It is interesting to note that the “sexual revolution” was sometimes portrayed as a communal utopia, whereas in fact it was simply another stage in the historical rise of individualism. As the lovely word “household” suggests, the couple and the family would be the last bastion of primitive communism in liberal society. The sexual revolution was to destroy these intermediary communities, the last to separate the individual from the market. The destruction continues to this day.

Or:

What the boy felt was something pure, something gentle, something that predates sex or sensual fulfillment. It was the simple desire to reach out and touch a loving body, to be held in loving arms. Tenderness is a deeper instinct than seduction, which is why it is so difficult to give up hope.

Or:

It's a curious idea to reproduce when you don't even like life.

And, most importantly:

Love binds, and it binds forever. Good binds while evil unravels. Separation is another word for evil; it is also another word for deceit.

Houellebecq plays the role of prophet of our kinless world, a world attempting to denude itself of intimacy and profound joy. And he is excellent at articulating the plight of the solitary sufferer, of telling us where we went wrong. He is sensitive to these metaphysical wrong turns because he is naturally a pessimist. This same pessimism that allows him clarity in one sense also blinds him to the ways in which we might recover or rebuild societal structures for encouraging human flourishing. He seems to understand that life without family-bonds or the church is terrible, but he has trouble saying why family is good.

For that we might turn to Christopher Lasch, the American historian and social critic. To understand Lasch’s defense of the family, we need to also know what he meant by “family”. So often, at least since the Second World War, when people say the word, the image that comes to mind is a nuclear family of husband, wife, and children. But Lasch wants us to understand that this emphasis on the nuclear family is itself a kind of neologism, a kind of larval stage of the kinless individualism we’re currently experiencing. As George Scialabbia summarizes Lasch’s take:

Far from idealizing the nuclear family, Lasch portrayed it as a doomed adaptation to industrial development. The transition from household production to mass production inaugurated a new world—a heartless world, to which the ideology of the family as a domestic sanctuary, a haven, was one response. The premodern, preindustrial family was besieged (and vanquished) by market forces; the modern family is besieged by the “helping” (which has turned out to mean “controlling”) professions. The latter development—the subordination of the family to the authority of a therapeutic ideology and an impersonal bureaucracy—is the story told in Haven in a Heartless World and its successors, the very well-known Culture of Narcissism and the not very well-known The Minimal Self.

A few things are happening here, Lasch tells us. Most people are familiar with the critique that market forces abolished the “productive household” of the extended homesteading family, forcing each individual to leave the home, starting with the father and the extending to the mother, in desperate search for financial security. But Lasch contends that this process continues psychologically by the various distant and abstract bureaucratic forces, the “helping” entities, which step in to take on a greater role in parenting children. Whereas familial authority was once experienced as something intimate and personal, it is now a far-off thing which the nuclear family is at pains to defend itself from. In Lasch’s formulation, a conscience is formed by a combination of love and authority. When the authority of a nuclear family is taken (as Lasch insists it always will be in a society bent on atomization), and it is left only with love, it is not too much of a leap to expect that children will be made into narcissists. Lasch defines the narcissist as:

Wary of intimate, permanent relationships, which entail dependence and thus may trigger infantile rage; beset by feelings of inner emptiness and unease . . . ; preoccupied with personal “growth” and the consumption of novel sensations; prone to alternating self-images of grandiosity and abjection; liable to feel toward everyone in authority the same combination of rage and terror that the infant feels for whoever it depends on; unable to identify emotionally with past and future generations and therefore unable to accept the prospect of aging, decay, and death.

Unfortunately, these traits strike us as being all-too familiar. We know them. They are the atomized individuals of our kinless world. They are us.

Lasch is critically incisive when it comes to describing how a family effectively socializes the young and generally makes itself useful, but one wonders if even an extended family network is able to defend itself against the vagaries of Houellebecq’s deceitful evil of “separation”. In order to guard against nihilism, the traditional family structure needs to be more than self-referential. What seems to be needed is a kind of spiritualized version of Lasch and Hourellebecq, defending kinship not in reactionary and secularized terms, but in the context of the metaphysical excess of which all goods partake.

Any proper defense of the family should take pains to avoid the logic and vocabulary of atomization, of things and people being ends unto themselves. As we have seen, this sort of overly simple rationalization tends to harvest the very results which it claims to defend against: the individual exalted becomes a forgotten bit of refuse, left to die in an apartment forgotten and alone. Channeling the late Wittgenstein, we can say that the secret to the family lies outside the family.

Not coincidentally, Pope Francis echoes Lasch’s use of the word “narcissism” in Amoris Laetitia to describe the qualities of someone enmeshed in our “culture of the ephemeral”:

Here I think, for example, of the speed with which people move from one affective relationship to another. They believe, along the lines of social networks, that love can be connected or disconnected at the whim of the consumer, and the relationship quickly “blocked.” I think too of the fears associated with permanent commitment, the obsession with free time, and those relationships that weigh costs and benefits for the sake of remedying loneliness, providing protection or offering some service. We treat affective relationships the way we treat material objects and the environment: everything is disposable; everyone uses and throws away, takes and breaks, exploits, and squeezes the last drop. Then, goodbye. Narcissism makes people incapable of looking beyond themselves, beyond their own desires and needs. Yet sooner or later, those who use others end up being used themselves, manipulated and discarded by that same mind-set. It is also worth noting that breakups occur among older adults who seek a kind of “independence” and reject the idea of growing old together, looking after and supporting one another” (§32-3).

So far, we could be reading Lasch or DelNoce, but where His Holiness parts ways with them is in acknowledging that “Scripture and Tradition give us access to a knowledge of the Trinity, which is revealed with the features of a family. The family is the image of God, who is a communion of persons” (§53). In other words, marriage and family both are more than sociological events. In a kind of spiritualization of Lasch’s description of the role of the family in psychological formation, we have marriage as a sacrament and family as symbolic confirmation of the higher order of reality, and we develop a deeper spiritual awareness through these relationships:

Marriage is a precious sign for “when a man and a woman celebrate the sacrament of marriage, God, as it were, is ‘mirrored’ in them; he impresses in them his own features and the indelible character of his love. Marriage is the icon of God’s love for us. Indeed, God is also communion: the three Persons of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit live eternally in perfect unity. And this is precisely the mystery of marriage: God makes of the two spouses a single existence” (§82).

What we are left with is the antithesis of Houellebecq’s evil “separation”.

Our new kinless world, where social lives are defined in large part by the harsh realities of the Second Demographic Transition, seems more then than simply the effect of material shifts and technological progress. What we might reduce “the lonely death” to is the severance of the symbolic nature of our human relationships to the divine. The etymology of “symbol” being “to join together”, we can say that our atomization, our unjoining (etymologically related to the word “diabolic,” dia-ballō, to divide) has occurred simultaneously on many levels. Unfixed from the cross, we are unmoored ourselves, and bereft. Separated from the Father we are without authority. Unjoined from the Son we are without love. Cleaved from the Holy Spirit we are left as the narrator in Eliot’s Wasteland: “On Margate Sands / I can connect / Nothing with nothing./ The broken fingernails of dirty hands.” Disposing of lonely corpses for a paycheck before eventually being disposed of ourselves, whenever we happen to be found . . . like junk.