This is my land, America. Naturally, I love it—it is home—and I am vitally concerned about its mores, its democracy, and its well-being. I try now to look at it with clear, unprejudiced eyes. My ancestry goes back at least four generations on American soil and, through Indian blood, many centuries more. My background and training is purely American—the schools of Kansas, Ohio, and the East. I am old stock as opposed to recent immigrant blood.

Yet many Americans who cannot speak English—so recent is their arrival on our shores—may travel about our country at will securing food, hotel, and rail accommodations wherever they wish to purchase them. I may not. These Americans, once naturalized, may vote in Mississippi or Texas, if they live there. I may not. They may work at whatever job their skills command. But I may not. They may purchase tickets for concerts, theatres, lectures wherever they are sold throughout the United States. Often I may not. They may repeat the Oath of Allegiance with its ringing phrase of “Liberty and justice for all,” with a deep faith in its truth—as compared with the limitations and oppressions they have experienced in the Old World. I repeat the oath, too, but I know that the phrase about “liberty and justice” does not fully apply to me. I am an American—but I am a colored American.

I know that all these things I mention are not all true for all localities all over America. Jim Crowism varies in degree from North to South, from the mixed schools and free franchise of Michigan to the tumbledown colored schools and open terrorat the polls of Georgia and Mississippi. All over America, however, against the Negro there has been an economic color line of such severity that since the Civil War we have been kept most effectively, as a racial group, in the lowest economic brackets. Statistics are not needed to prove this. Simply look around you on the Main Street of any American town or city. There are no colored clerks in any of the stores—although colored people spend their money there. There are practically never any colored street-car conductors or bus drivers—although these public carriers run over streets for which we pay taxes. There are no colored girls at the switchboards of the telephone company—but millions of Negroes have phones and pay their bills. Even in Harlem, nine times out of ten, the man who comes to collect your rent is white. Not even that job is given to a colored man by the great corporations owning New York real estate. From Boston to San Diego, the Negro suffers from job discrimination.

Yet America is a land where, in spite of its defects, I can write this article. Here the voice of democracy is still heard—Wallace, Willkie, Agar, Pearl Buck, Paul Robeson, Lillian Smith. America is a land where the poll tax still holds in the South—but opposition to the poll tax grows daily. America is a land where lynchers are not yet caught—but Bundists are put in jail, and majority opinion condemns the Klan. America is a land where the best of all democracies has been achieved for some people—but in Georgia, Roland Hayes, world-famous singer, is beaten for being colored and nobody is jailed—nor can Mr. Hayes vote in the State where he was born. Yet America is a country where Roland Hayes can come from a log cabin to wealth and fame—in spite of the segment that still wishes to maltreat him physically and spiritually, famous though he is.

This segment, the South, is not all of America. Unfortunately, however, the war with its increased flow of white Southern workers to Northern cities, has caused the Jim Crow patterns of the South to spread all over America, aided and abetted by the United States Army. The Army, with its policy of segregated troops, has brought Jim Crow into communities where it was but little, if at all, in existence before Pearl Harbor. From Camp Custer in Michigan to Guadalcanal in the South Seas, the Army has put its stamp upon official Jim Crow, in imitation of the Southern states where laws separating Negroes and whites are as much a part of government as are Hitler’s laws segregating Jews in Germany. Therefore, any consideration of the current problems of the Negro people in America must concern itself seriously with the question of what to do about the South.

The South opposes the Negro’s right to vote, and this right is denied us in most Southern states. Without the vote a citizen has no means of protecting his constitutional rights. For Democracy to approach its full meaning, the Negro all over America must have the vote. The South opposes the Negro’s right to work in industry. Witness the Mobile shipyard riots, the Detroit strikes fomented by Southern whites against the employment of colored people, the Baltimore strikes of white workers who objected to Negroes attending a welding school which would give them the skill to rate upgrading. For Democracy to achieve its meaning, the Negro like other citizens must have the right to work, to learn skilled trades, and to be upgraded.

The South opposes the civil rights of Negroes and their protection by law. Witness lynchings where no one is punished, witness the Jim Crow laws that deny the letter and spirit of the Constitution. For Democracy to have real meaning, the Negro must have the same civil rights as any other American citizen. These three simple principles of Democracy—the vote, the right to work, and the right to protection by law—the South opposes when it comes to me. Such procedure is dangerous for all America. That is why, in order to strengthen Democracy, further the war effort, and achieve the confidence of our colored allies, we must institute a greater measure of Democracy for the eight million colored people of the South. And we must educate the white Southerners to an understanding of such democracy, so they may comprehend that decency toward colored peoples will lose them nothing, but rather will increase their own respect and safety in the modern world.

I live on Manhattan Island. For a New Yorker of color, truthfully speaking, the South begins at Newark. A half-hour by tube from the Hudson Terminal, one comes across street-corner hamburger stands that will not serve a hamburger to a Negro customer wishing to sit on a stool. For the same dime a white pays, a Negro must take his hamburger elsewhere in a paper bag and eat it, minus a plate, a napkin, and a glass of water. Sponsors of the theory of segregation claim that it can be made to mean equality. Practically, it never works out that way. Jim Crow always means less for the one Jim Crowed and an unequal value for his money—no stool, no shelter, merely the hamburger, in Newark.

As the colored traveller goes further South by train, Jim Crow increases. Philadelphia is ninety minutes from Manhattan. There the all-colored grammar school begins its separate education of the races that Talmadge of Georgia so highly approves. An hour or so further down the line is Baltimore where segregation laws are written in the state and city codes. Another hour by train, Washington. There the conductor tells the Negro traveller, be he soldier or civilian, to go into the Jim Crow coach behind the engine, usually half a baggage car, next to trunks and dogs.

That this change to complete Jim Crow happens at Washington is highly significant of the state of American democracy in relation to colored peoples today. Washington is the capital of our nation and one of the great centers of the Allied war effort toward the achievement of the Four Freedoms. To a southbound Negro citizen told at Washington to change into a segregated coach the Four Freedoms have a hollow sound, like distant lies not meant to be the truth.

The train crosses the Potomac into Virginia, and from there on throughout the South life for the Negro, by state law and custom, is a hamburger in a sack without a plate, water, napkin, or stool—but at the same price as the whites pay—to be eaten apart from the others without shelter. The Negro can do little about this because the law is against him, he has no vote, the police are brutal, and the citizens think such caste-democracy is as it should be.

For his seat in the half-coach of the crowded Jim Crow car, a colored man must pay the same fare as those who ride in the nice air-cooled coaches further back in the train, privileged to use the diner when they wish. For his hamburger in a sack served without courtesy the Southern Negro must pay taxes but refrain from going to the polls, and must patriotically accept conscription to work, fight, and perhaps die to regain or maintain freedom for people in Europe or Australia when he himself hasn’t got it at home. Therefore, to his ears most of the war speeches about freedom on the radio sound perfectly foolish, unreal, high-flown, and false. To many Southern whites, too, this grand talk so nobly delivered, so poorly executed, must seem like play-acting. Liberals and persons of goodwill, North and South, including, no doubt, our President himself, are puzzled as to what on earth to do about the South—the poll-tax South, the Jim Crow South—that so shamelessly gives the lie to Democracy. With the brazen frankness of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, Dixie speaks through Talmadge, Rankin, Dixon, Arnall, and Mark Ethridge.

In a public speech in Birmingham, Mr. Ethridge says: “All the armies of the world, both of the United States and the Axis, could not force upon the South an abandonment of racial segregation.” Governor Dixon of Alabama refused a government war contract offered Alabama State Prison because it contained an anti-discrimination clause which in his eyes was an “attempt to abolish segregation of races in the South.” He said: “We will not place ourselves in a position to be attacked by those who seek to foster their own pet social reforms.” In other words, Alabama will not reform. It is as bull-headed as England in India, and its governor is not ashamed to say so.

As proof of Southern intolerance, almost daily the press reports some new occurrence of physical brutality against Negroes. Former Governor Talmadge was “too busy” to investigate when Roland Hayes and his wife were thrown into jail, and the great tenor beaten, on complaint of a shoe salesman over a dispute as to what seat in his shop a Negro should occupy when buying shoes. Nor did the governor of Mississippi bother when Hugh Gloster, professor of English at Morehouse College, riding as an inter-state passenger, was illegally ejected from a train in his state, beaten, arrested, and fined because, being in an overcrowded Jim Crow coach, he asked for a seat in an adjacent car which contained only two white passengers.

Legally, the Jim Crow laws do not apply to inter-state travellers, but the FBI has not yet gotten around to enforcing that Supreme Court ruling. En route from San Francisco to Oklahoma City, Fred Wright, a county probation officer of color, was beaten and forced into the Texas Jim Crow coach on a transcontinental train by order of the conductor in defiance of federal law. A seventy-six-year-old clergyman, Dr. Jackson of Hartford, Connecticut, going South to attend the National Baptist Convention, was set upon by white passengers for merely passing through a white coach on the way to his own seat. There have been many similar attacks upon colored soldiers in uniform on public carriers. One such attack resulted in death for the soldier, dragged from a bus and killed by civilian police. Every day now, Negro soldiers from the North, returning home on furlough from Southern camps, report incident after incident of humiliating travel treatment below the Mason-Dixon line.

It seems obvious that the South does not yet know what this war is all about. As answer Number One to the question, “What shall we do about the South?” I would suggest an immediate and intensive government-directed program of pro-democratic education, to be put into the schools of the South from the first grades of the grammar schools to the universities. As part of the war effort, this is urgently needed. The Spanish Loyalist Government had trench schools for its soldiers and night schools for civilians even in Madrid under siege. America is not under siege yet. We still have time (but not too much) to teach our people what we are fighting for, and to begin to apply those teachings to race relations at home. You see, it would be too bad for an emissary of color from one of the Latin American countries, say Cuba or Brazil, to arrive at Miami Airport and board a train for Washington, only to get beaten up and thrown off by white Southerners who do not realize how many colored allies we have—nor how badly we need them—and that it is inconsiderate and rude to beat colored people, anyway.

Because transportation in the South is so symbolic of America’s whole racial problem, the Number Two thing for us to do is study a way out of the Jim Crow car dilemma at once. Would a system of first, second, and third-class coaches help? In Europe, formerly, if one did not wish to ride with peasants and tradespeople, one could always pay a little more and solve that problem by having a first class compartment almost entirely to oneself. Most Negroes can hardly afford parlor car seats. Why not abolish Jim Crow entirely and let the whites who wish to do so, ride in coaches where few Negroes have the funds to be? In any case, our Chinese, Latin American, and Russian allies are not going to think much of our democratic pronunciamentos as long as we keep compulsory Jim Crow cars on Southern rails.

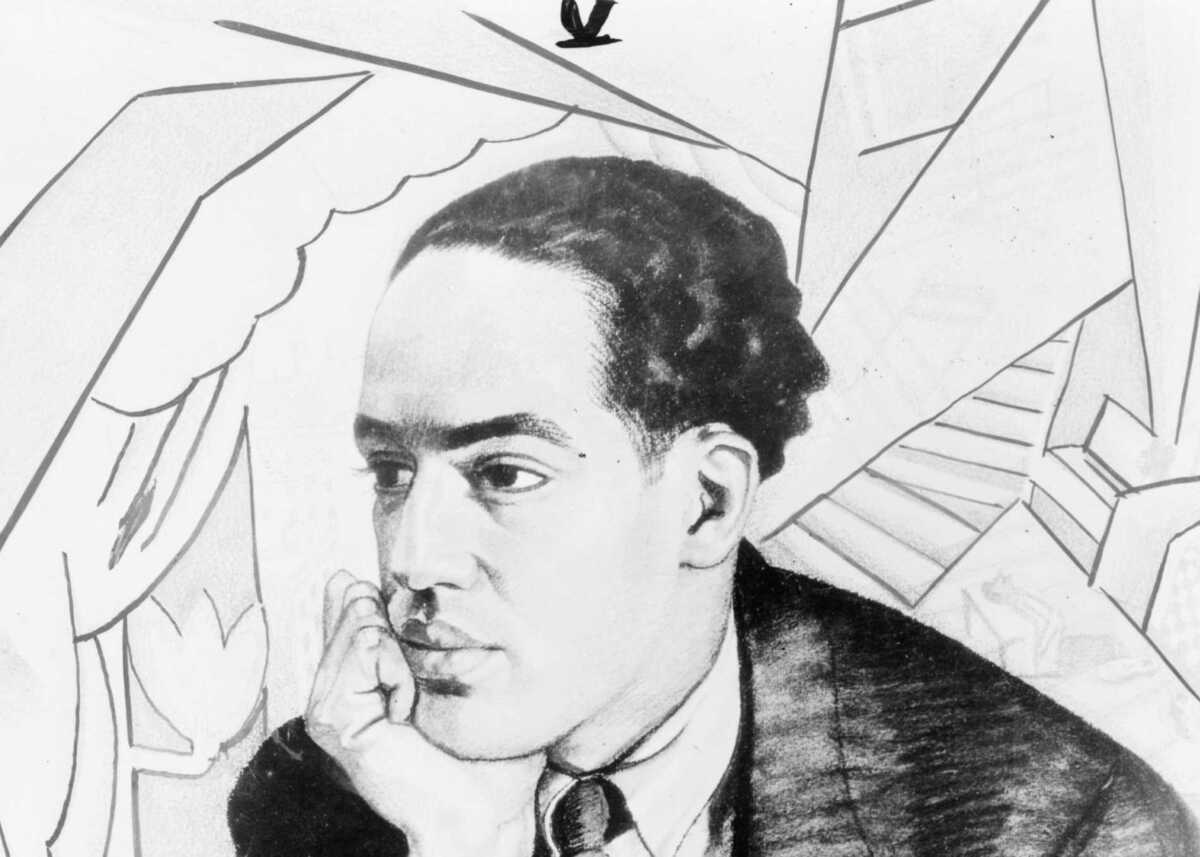

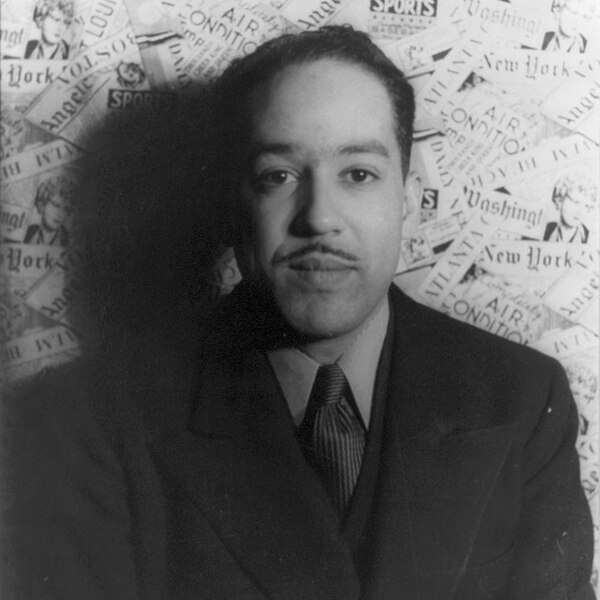

Since most people learn a little through education, albeit slowly, as Number Three, I would suggest that the government draft all the leading Negro intellectuals, sociologists, writers, and concert singers from Alain Locke of Oxford and W. E. B. Du Bois of Harvard to Dorothy Maynor and Paul Robeson of Carnegie Hall and send them into the South to appear before white audiences, carrying messages of culture and democracy, thus off-setting the old stereotypes of the Southern mind and the Hollywood movie, and explaining to the people without dialect what the war aims are about. With each, send on tour a liberal white Southerner like Paul Green, Erskine Caldwell, Pearl Buck, Lillian Smith, or William Seabrook. And, of course, include soldiers to protect them from the fascist-minded among us.

Number Four, as to the Army—draftees are in sore need of education on how to behave toward darker peoples. Just as a set of government suggestions has been issued to our soldiers on how to act in England, so a similar set should be given them on how to act in Alabama, Georgia, Texas, Asia, Mexico, and Brazil—wherever there are colored peoples. Not only printed words should be given them, but intensive training in the reasons for being decent to everybody. Classes in democracy and the war aims should be set up in every training camp in America and every unit of our military forces abroad. These forces should be armed with understanding as well as armament, prepared for friendship as well as killing.

I go on the premise that most Southerners are potentially reasonable people, but that they simply do not know nowadays what they are doing to America, or how badly their racial attitudes look toward the rest of the civilized world. I know their politicians, their schools, and the Hollywood movies have done their best to uphold prevailing reactionary viewpoints. Heretofore, nobody in America except a few radicals, liberals, and a handful of true religionists have cared much about either the Negroes or the South. Their sincere efforts to effect a change have been but a drop in a muddy bucket. Basically, the South needs universal suffrage, economic stabilization, a balanced diet, and vitamins for children. But until those things are achieved, on a lesser front to ameliorate—not solve—the Negro problem (and to keep Southern prejudice from contaminating all of America) a few mild but helpful steps might be taken.

It might be pointed out to the South that the old bugaboo of sex and social equality doesn’t mean a thing. Nobody as a rule sleeps with or eats with or dances with or marries anybody else except by mutual consent. Millions of people of various races in New York, Chicago, and Seattle go to the same polls and vote without ever co-habiting together. Why does the South think it would be otherwise with Negroes were they permitted to vote there? Or to have a decent education? Or to sit on a stool in a public place and eat a hamburger? Why they think simple civil rights would force a Southerner’s daughter to marry a Negro in spite of herself, I have never been able to understand. It must be due to some lack of instruction somewhere in their schooling.

A government-sponsored educational program of racial decency could, furthermore, point out to its students that cooperation in labor would be to the advantage of all—rather than to the disadvantage of anyone, white or black. It could show quite clearly that a million unused colored hands barred out of war industries might mean a million weapons lacking in the hands of our soldiers on some foreign front—therefore a million extra deaths—including Southern white boys needlessly dying under Axis fire—because Governor Dixon of Alabama and others of like mentality need a little education. It might also be pointed out that when peace comes and the Southerners go to the peace table, if they take there with them the traditional Dixie racial attitudes, there is no possible way for them to aid in forming any peace that will last. China, India, Brazil, Free French Africa, Soviet Asia and the whole Middle East will not believe a word they say.

Peace only to breed other wars is a sorry peace indeed, and one that we must plan now to avoid. Not only in order to win the war then, but to create peace along decent lines, we had best start now to educate the South—and all America—in racial decency. That education cannot be left to well-meaning but numerically weak civilian organizations. The government itself should take over—and vigorously. After all, Washington is the place where the conductor comes through every southbound train and tells colored people to change to the Jim Crow car ahead.

That car, in these days and times, has no business being “ahead” any longer. War’s freedom train can hardly trail along with glory behind a Jim Crow coach. No matter how streamlined the other cars may be, that coach endangers all humanity’s hopes for a peaceful tomorrow. The wheels of the Jim Crow car are about to come off and the walls are going to burst wide open. The wreckage of Democracy is likely to pile up behind that Jim Crow car, unless America learns that it is to its own self-interest to stop dealing with colored peoples in so antiquated a fashion. I do not like to see my land, America, remain provincial and unrealistic in its attitudes toward color. I hope the men and women, of goodwill here of both races will find ways of changing conditions for the better.

Certainly it is not the Negro who is going to wreck our Democracy. (What we want is more of it, not less.) But Democracy is going to wreck itself if it continues to approach closer and closer to fascist methods in its dealings with Negro citizens—for such methods of oppression spread, affecting other whites, Jews, the foreign born, labor, Mexicans, Catholics, citizens of Oriental ancestry—and, in due time, they boomerang right back at the oppressor. Furthermore, American Negroes are now Democracy’s current test for its dealings with the colored peoples of the whole world of whom there are many, many millions—too many to be kept indefinitely in the position of passengers in Jim Crow cars.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is an excerpt from What the Negro Wants, edited by Rayford W. Logan. Originally published in 1944, this edition includes Rayford Logan’s introduction to the 1969 reprint, a new introduction by Kenneth Janken, and an updated bibliography. It is part of an ongoing collaboration with the University of Notre Dame Press. You can read our excerpts from this collaboration here. All rights reserved.