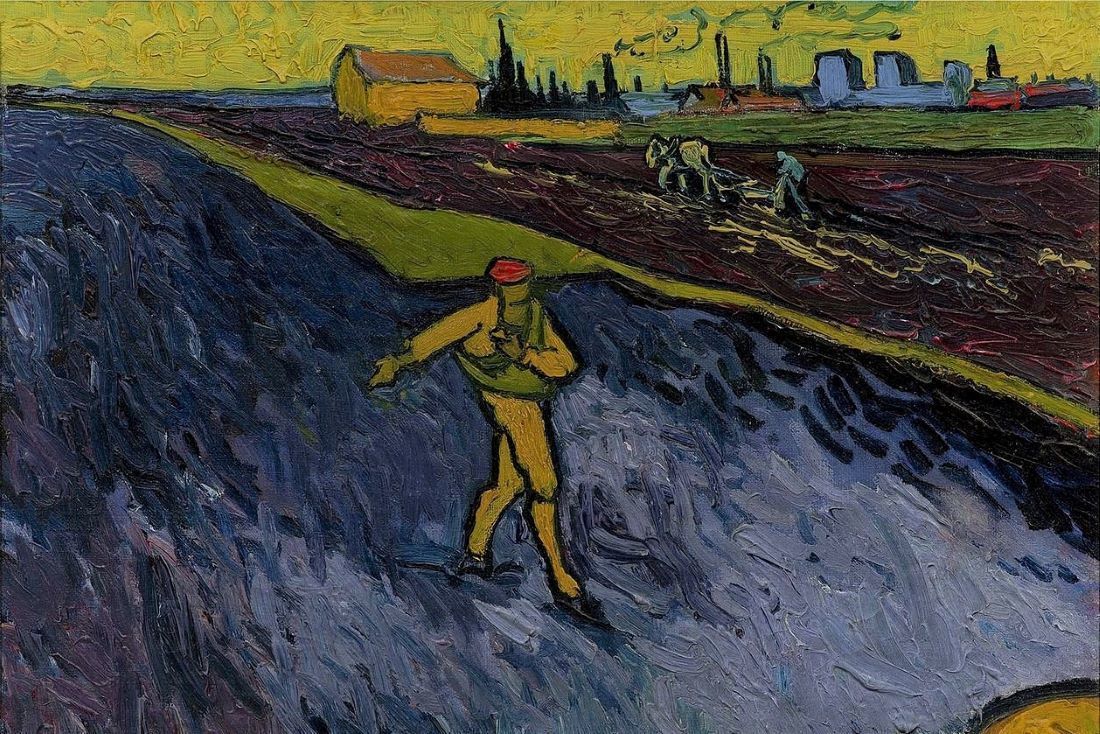

A sower went out to sow. And as he sowed, some seed fell on the path, and birds came and ate it up. Some fell on rocky ground, where it had little soil. It sprang up at once because the soil was not deep, and when the sun rose it was scorched, and it withered for lack of roots. Some seed fell among thorns, and the thorns grew up and choked it. But some seed fell on rich soil, and produced fruit, a hundred or sixty or thirtyfold.

—Matt 13:3-8

In a recent statement, Archbishop Viganò reduces Vatican II to a seedbed of contemporary error animated by the spirit of “Masonry.” I do sympathize with his frustrations regarding the evident confusion in the Church today, the attenuation of Eucharistic faith, the banality of much of what claims to be the Council’s inheritance liturgically, etc.

Yet, is it fair to blame the Council, rejecting it as riddled with error? But would this not mean the Holy Spirit allowed the Church to lapse into prodigious error and further allowed five Popes to teach it enthusiastically for over 50 years? That claim would seem to be the triumph of “Masonry!” Viganò says,

Among other things, this Council has proven to be the only one that has caused so many interpretative problems and so many contradictions with respect to the preceding Magisterium, while there is not one other council—from the Council of Jerusalem to Vatican I—that does not harmonize perfectly with the entire Magisterium or that needs so much interpretation.

However, the Council of Nicaea (325) was controversial from the very moment it closed. Its teaching was only clarified after nearly 60 years of controversy in 381 at the Council of Constantinople. Was Nicaea consistent with previous magisterial teaching? Yes, as clarified in 381, but in its immediate aftermath some thought the homoousios contradicted the condemnation of Paul of Samosata, who did not believe the Son was a distinct Person, or likewise vindicated the heresy of Sabellianism.

Chalcedon (451) may be the Council whose legacy was contested the longest. The next three ecumenical Councils were attempts to grapple with its reception and its relationship to the teaching of Ephesus (431). Nor was there lack of political complexity, within both Church and society, to add to the need for clarification.

Further, did the Second Vatican Council really produce no good worth mentioning? Viganò mentions none. True, its liturgical reforms were commandeered by banality in the United States. For example, there is the introduction of hymns with no aesthetic merit but containing doctrinal errors especially regarding the Eucharist, hymns that de-catechized the very Catholics who faithfully attend Sunday Mass.

But it is equally true, for example, that the reforms produced the beautiful inculturated liturgies in churches across Africa. I attended a Mass celebrated according to the Rite of Zaire in an isolated region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It fully expressed the spirit of the liturgy of the universal Church not in spite of its being celebrated in an unmistakably African voicing, but because of it. In chant and in movement it communicated a dignity commensurate with the “awfulness of the Sacrifice,” as Servant of God Dorothy Day once put it, while clothing it in an un-self-conscious warmth appropriate to the “Sacrament of Charity.”

Another example is a Mass I attended in Abuja, celebrating the ordination of five new priests. The languages, the liturgical gestures, were eclectic. They reflected traditions of Gregorian chant and English hymnody, and a variety of Igbo language hymns and liturgical customs from the new priests’ home villages. But it was all integrated by the deepest conviction of dignity and joy flowing from the Eucharist itself. When, after Communion, the whole assembly recited in unison three times, “O Sacrament Most Holy, O Sacrament Divine, all praise and all thanksgiving be every moment Thine,” it seemed that the Holy Spirit was making the deepest possible appeal to our hearts, reaching into our souls, helping us to “pray as we ought.”

Perhaps those of us blaming our own banality of imagination on Vatican II should get out of the house a little and have the humility to learn from others whom we may customarily look down upon as unenlightened?

Further, what about the many beautiful truths that found their most robust magisterial expression in Lumen Gentium? Do we leave behind the exposition of the universal call to holiness? But, it is something which seemed so sublime to me when I first read it at age 19 that the desire to live up to it has never worn off even now. What about the recovery of patristic preaching on the priesthood of the baptized? That is a project which the Council of Trent left for a future age to undertake (Trent was necessarily more focused on correcting the Reformers’ rejection of Holy Orders). Is the most maturely developed articulation of the three degrees of Holy Orders, incorporating but surpassing in precision anything preceding, to be discarded? Are these advances really the work of Masonry?

And, can we not count as an achievement, and not an error, the clarification that the one true Church of Jesus Christ, organized as a visible society, subsists in the Catholic Church? Is it really “Masonry” to find some way of validating the genuine bonds of communion that link separated communions to the Catholic Church? If there are no such genuine bonds, then it is also incoherent to say that the one true Church organized as a visible society is the Catholic Church, because recognizing it as such requires recognizing all the bonds of visible communion as such—including those that remain present in other communions and thus link them to us.

Would we not want to find language allowing us to celebrate the degree of communion preserved with the Coptic Christians whose recent heroic witness “to the point of shedding blood” moved the one non-Christian among them to elect a baptism by blood? Is it not beautiful to be able to say, with the Catechism’s summary of conciliar teaching, that “Christ’s Spirit uses these [separated] Churches and ecclesial communities as means of salvation,” while qualifying that their “power derives from the fullness of grace and truth that Christ has entrusted to the Catholic Church” (CCC §819)? Is this Masonry? Or is it plainly Catholic truth, expressed more fully than in pre-Conciliar formulations? The treatment of this issue by Monsignor Gerard Philips, L’Église et son mystère au II Concile du Vatican (Volume 1, 1967, 117) is worth revisiting.

Relatedly, are we really willing to return to a legalistic interpretation of “There is no salvation outside the Church” that leaves the witness of these Coptic martyrs and others in ambiguity? Philips shows how patristic understanding of this phrase arose in controversies which envisioned counter-claims by heretics, not envisioning situations, such as those considered both by Pius IX and Pius XII regarding souls who find themselves outside of the visible bounds of the Catholic Church through no fault of their own (See: Philips, 192-93).

Is the rigorist understanding of the patristic dictum truly and fully Catholic teaching (and truly patristic)? Or does Vatican II, rather, express that teaching most fully? The Catechism summarizes (§847-48) in a way that I have found useful in freeing undergraduates from a loathing of the Church based on an illusory triumphalism.

Viganò says the “seeds” for contemporary errors were planted at Vatican II, and now we see from their bad fruit that the seed itself was bad. Does this stand up to scrutiny or was there something in the soil? Dei Verbum taught that the human authors of Scripture were “true authors.” Thus the interpreter must “take into account the conditions of their time and culture,” etc. (DV §11-12). Is this a bad seed because it was used by biblical scholars to promote the hegemony of historico-critical methods so much that eventually no other options were even imagined?

Yet, Dei Verbum equally teaches that the Scriptures “have God as their author and have been handed on as such to the Church herself,” and so, among other things, must be read “within the living Tradition of the whole Church” (see DV §11-12, CCC §106, 113). A truth only half received can be the seed of error, but through no fault of the truth, but rather of a certain laziness on the part of theologians (like myself!) who settled for a method of biblical interpretation that ended up regarding the exegesis of Church councils (including that of Vatican II) as “pre-critical” impositions on the text.

Another example, sticking with Dei Verbum: Is the relativism that de facto (if not de jure) is the implicit operating assumption of much interreligious dialogue the fault of Vatican II, even though Dei Verbum clearly states that “The Christian economy . . . since it is the new and definitive Covenant, will never pass away; and no new public revelation is to be expected before the glorious manifestation of our Lord Jesus Christ” (DV §4, CCC §66)?

Is it the fault of Nostra aetate that theologians (like myself!) have been content to allow the relativism of post-modern culture to operate as an implicit default mode? To emphasize Nostra aetate’s (true!) claim that there is truth in other religions without working equally hard to articulate at the same time how Jesus Christ is the unsurpassable seal on revelation? How would one even recognize truth in other religions did we not already in our own have the fullness of truth whereby to recognize it elsewhere?

Is Vatican II a bad seed? Or, is the seed in question rather the lopsided choice of theologians to develop one strand of conciliar teaching at the expense of others? Not to mention pastors who have so prioritized the true good of making Christian teaching accessible and intelligible to modern people that they downplay its uniqueness as embarrassingly outmoded? I understand the instinct, teaching so many students who think they are looking for just such intelligibility and only that, yet who discover they were actually seeking so much more if you actually give them that “more,” too.

Viganò’s letter has at least had the virtue of forcing me to emerge from complacency in accepting half-measures in the reception of the Council. Perhaps others will find themselves with me in the same boat as well.

EDITORIAL NOTE: An earlier version of this essay appeared in the online version of Inside the Vatican in their Moynihan Letters series. This essay and others in the series will be published in the August-September print issue of Inside the Vatican which will go to press in a few days.