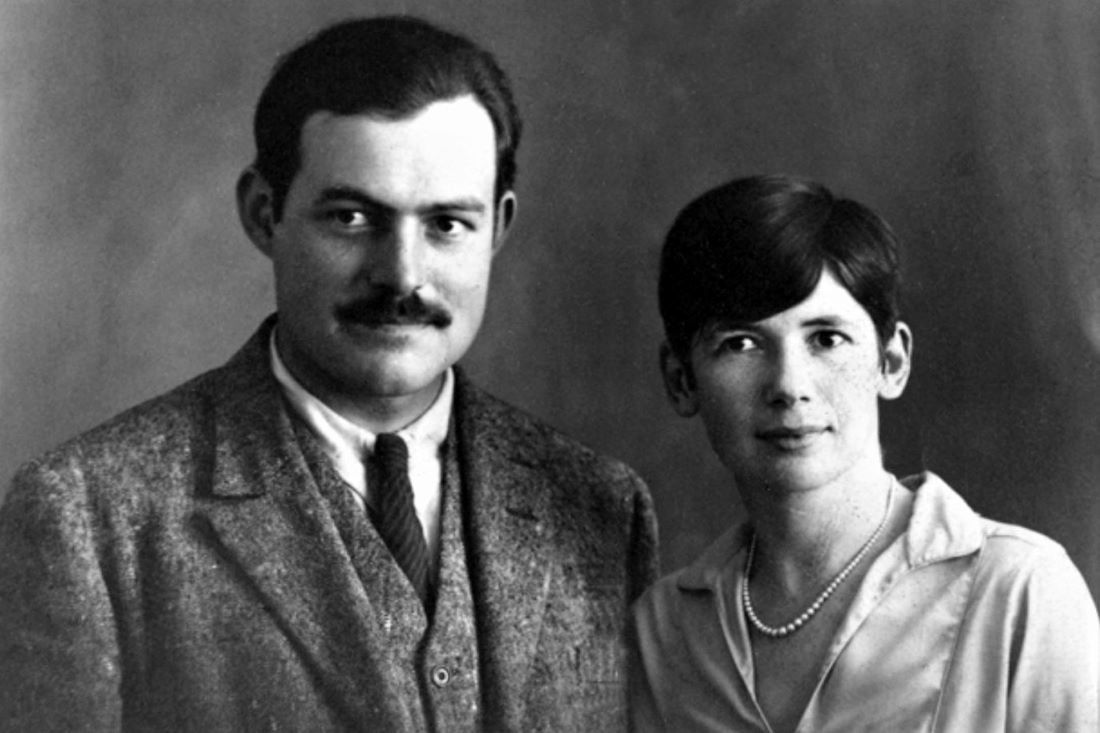

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) and Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) co-habited this earth for a space of 36 years, from 1925, when O’Connor was born, to 1961, when Hemingway died, but their lives could not have been more different. While Hemingway partied at bullfights in Pamplona, hunted lions in Africa, and battled mighty marlin off the coast of Cuba, O’Connor lived quietly on her mother’s dairy farm in rural Georgia, writing fiction for two hours a day and tending to her brood of forty peacocks.

While Hemingway carried on a famously tempestuous love life, marrying four times and falling in love many more, O’Connor remained single and solitary, falling in love only once with a travelling book salesman who did not return her affection. While Hemingway published in major magazines and received many distinguished honors during his larger-than-life lifetime, culminating in the Nobel Prize in 1954, O’Connor labored in relative obscurity, publishing in small literary journals, winning minor prizes, and feeling the sting of being denied a Guggenheim.

As Flannery O’Connor once predicted, “There won’t be any biographies of me for only one reason, life spent between the house and the chicken yard do not make for exciting copy” (The Habit of Being 290). By contrast, Hemingway had to fend off his would-be biographers, all of whom wanted to capture the truth of the private man behind the public myth.

Despite their differences, Hemingway and O’Connor share some key commonalities. First, their work would survive them, becoming increasingly more valued after their deaths (especially O’Connor’s) until both would be numbered among the finest writers of American fiction of the twentieth century. Second, both were Catholic writers, albeit Catholic writers of a markedly different stamp—so much so that most readers are surprised to learn that Ernest Hemingway and Flannery O’Connor shared the same faith.

Hemingway and O’Connor: Catholic Writers

Much of the groundwork establishing Hemingway’s identity as a Catholic writer was expertly laid by H.R. Stoneback’s seminal work in this area, including his 1991 essay, “In the Nominal Country of the Bogus: Hemingway’s Catholicism and the Biographies.” This terrain is further explored by more recent scholarship, including Matthew Nickel’s study, Hemingway’s Dark Night. Stoneback argues that the origins of Hemingway’s conversion are evident well before his marriage to his devoutly Catholic second wife Pauline Pfeiffer, and are rooted in his wounding in Italy in 1918, where he was tended to in a field hospital by a priest distributing viaticum and administering the sacrament of extreme unction. Stoneback presents overwhelming evidence that over the next 40 years Hemingway’s Catholic practice grew.

His observances included habitual prayer, “attending Mass, eating fish on Fridays, having Masses said for friends and family, donating thousands of dollars to the churches in Key West and Idaho, celebrating saints days, and revisiting important pilgrimage sites and cathedrals” (Hemingway’s Dark Night, 15). In addition to this regular practice, Hemingway famously gave his Nobel Prize medal as a votive offering to the Virgin of Charity of Cobre, and his funeral service was presided over by a Catholic priest.

Hemingway was keenly aware of the ways in which his life did not conform to Church teaching—four marriages and three divorces would certainly suggest that he did not keep all of the rules of the Church. Nevertheless, all three of Hemingway’s children—Jack, Patrick, and Gregory— were brought up Catholic, and he always identified as such. This identification, however, did not spill over into his public, literary life. He explains his reticence about advertising his faith in an unpublished letter to a priest friend, Fr. Vincent Donovan:

I have always had more faith than intelligence or knowledge and I have never wanted to be known as a Catholic writer because I know the importance of setting an example—and I have never set a good example . . . Also I am a very dumb Catholic and I have so much faith that I hate to examine into it.” (December 1927, JFK Library, quoted in Stoneback, “In the Nominal Country,” 16).

As this passage might suggest, Hemingway could not be a more different kind of Catholic writer than Flannery O’Connor, who, unlike Hemingway, very much wanted and did “examine into” her faith. A cradle Catholic, rather than a convert, and a voluminous reader of theology, O’Connor wrote hundreds of letters as well as essays, journal entries, and reviews, which explore fine points of Catholic teaching and trace the relationship between her work as an artist and her identity as a Catholic. Also unlike Hemingway, she was transparent about the religious tradition she belonged to. If she was occasionally reluctant to be labeled as a Catholic writer, it was primarily because Catholic writers were not taken seriously, either by the secular literary world or by the Church.

According to O’Connor, the Church faulted Catholic writers for not being sufficiently positive, uplifting and didactic, while the literary establishment assumed that belief in God and religious practice limited the vision of an artist. O’Connor’s answer to these erroneous assumptions about the relationship between art and faith can be summed up in a statement she makes in her essay, “Catholic Novelists and Their Readers”:

St. Thomas Aquinas says that art . . . is wholly concerned with the good of that which is made . . . The artist has his hands full and does his duty if he attends to his art. He can safely leave evangelizing to the evangelists (Mystery and Manners, 171).

The Catholic writer is not a purveyor of religion, but is, if she is a good writer, an artist who is “hotly in pursuit of the real” (171). Because she writes with “the whole personality” (101), her fiction is going to be infused, colored, and shaped by Catholic thought, language, and imagery. Because the Catholic “lives in a larger universe,” one in which “the natural world contains the supernatural” (175). The Catholic writer is always reaching beyond the ordinary limits naturalistic novelists abide by, enabling the writer to map out new terrain and make it her own.

This is something that both Hemingway and O’Connor excelled at. A discerning reader can recognize a Hemingway or an O’Connor story a mile away, not only on account of their signature styles, but also because the fictional universes they create are suffused with the Catholic themes of suffering, violence, and redemption.

“Pierced”

One of the subtitles that I considered for this essay is “pierced”—a word and an image that highlights a deep affinity between Hemingway and O’Connor. The experience of being “pierced” and its attendant dark night of the soul shaped them, honed their sensibilities, and made them the human beings they were and the writers they would become. This would be their focus and obsession all their lives—the ways in which people suffer, the purpose and power of suffering, its pathos and its terrible beauty.

This preoccupation is inevitably traceable to the fact that both O'Connor and Hemingway were Catholics. They practiced a faith whose central image is the figure of a human being who is pierced—by five wounds, to be precise—tortured, bloodied, and slowly dying on the cross. Their own personal suffering gave them both a taste of the cross and made them aware of its reality—not as a symbol but as a statement of fact. This is the essence of the human condition: we are born, we suffer, and we die. What do we do in the face of that terrible fact is the subject of their writing.

Both Flannery and Ernest were pierced young. Ernest suffered the catastrophic shrapnel wounding at the age of 19 that would mark him for life, in addition to experiencing the trauma of witnessing his fellow human beings slaughtered all around him during World War I. Flannery suffered a crippling bout of Lupus at age 25, which utterly changed the trajectory of her life. She lived with the knowledge that the disease would bring years of chronic pain and, most likely, premature death, and she would have to live with its terrible effects—the gradual dissolution of her bones, the loss of the ability to walk without crutches, the necrosis of her jaw, which severely restricted eating, are just a few of the symptoms she endured.

In addition to this, Flannery and Ernest both experienced tragic loss young. Both lost their fathers—O'Connor to Lupus when she was 15 and Hemingway to suicide when he was 29. In addition to having to watch their fathers suffer, they would both inherit their fathers' illnesses—Flannery her father's Lupus, Ernest his father's depression—and both would eventually die of the same cruel malady that ultimately killed their fathers. Their personal suffering attuned them to the suffering of others. They wrote stories and novels that explored the role of suffering in the lives of their characters, characters who were often versions of themselves and the people around them.

Violence

As a result of this involuntary initiation into the transformative power of pain, both Hemingway’s and O’Connor’s stories contain a great deal of violence. A quick list of the typical events that occur in O’Connor’s stories is enough to cast a pall on any happy conversation. Her stories feature serial killers, accidental shootings, domestic murder, sudden death by stroke, child suicide, death by tractor, intentional drowning, and homosexual rape, to name a few. O’Connor is unequivocal in her commitment to violence as a means of awakening her characters to their profound flaws, their spiritual peril, and their need for redemption:

In my . . . stories I have found that violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace. Their heads are so hard that almost nothing else will do the work” (“On Her Own Work,” Mystery and Manners, 112).

In O’Connor’s stories, violence breaks open even the most hardheaded human beings and orders them to a “new vision” of reality (The Habit of Being, 275). It also tests them, presenting them with choices that lead to self-discovery and self-revelation. In O’Connor’s words,

With the serious writer, violence is never an end in itself. It is the extreme situation that best reveals what we are essentially . . . The man in the violent situation reveals those qualities least dispensable in his personality, those qualities which are all he will have to take into eternity with him.” (“On Her Own Work,” Mystery and Manners, 113-114)

This paragraph is uncannily reminiscent of Hemingway’s concept of “grace under pressure,” a phrase that has been variously parsed as “guts,” courage, and the ability to maintain dignity and self-control in challenging circumstances (April 20, 1926, letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald. Reprinted in Ernest Hemingway: Selected Letters 1917-1961, 199-201).

Hemingway’s ideal model of grace under pressure is the matador, the man who faces down death in the form of a half-ton wild bull, and with the aid of a sword and a flimsy piece of flannel kills him. Not only does he kill him, he makes of the process performance art, as he maintains his poise and uses his superior knowledge and experience to defeat death. Here is his description of young Pedro Romero’s killing of his last bull in the bullring in The Sun Also Rises:

The bull’s tail went up and he charged, and Romero moved his arms ahead of the bull, wheeling, his feet firmed. The dampened, mud-weighted cape swung open and full as a sail fills, and Romero pivoted with it just ahead of the bull. At the end of the pass they were facing each other again. Romero smiled. The bull wanted it again, and Romero’s cape filled again, this time on the other side. Each time he let the bull pass so close that the man and the bull and the cape that filled and pivoted ahead of the bull were all one sharply etched mass. It was all so slow and so controlled. It was as though he were rocking the bull to sleep. He made four veronicas like that, and finished with a half-veronica that turned his back on the bull and came away toward the applause, his hand on his hip, his cape on his arm, and the bull watching his back going away (The Sun Also Rises 221).

The grace of Romero’s performance with the bull is matched by the grace of Hemingway’s prose in this passage, the measured motion of the matador echoed in the repeated words and sounds and syntax, the launch and return of each veronica and each sentence.

The ritual violence of the bullfight differs from O’Connor’s more random, shocking incidents of violence. Violence breaks unexpectedly into the lives of O’Connor’s characters, whereas in many of Hemingway’s stories, violence is the constant thrum beneath the surface of daily living, unspoken but very much present. One of the reasons Hemingway values the ritual enacting of bullfighting is that while it involves both suffering and violence, the violence can, to some degree, be controlled. Man can defeat death, in the form of the bull, if only temporarily. And while it is true that the bull can, and sometimes does, kill the man, as Hemingway notes in the voice of Santiago of The Old Man and the Sea, “a man can be destroyed but not defeated” (103).

O’Connor feels similarly about her characters who are felled by violent death. The annoying grandmother in the story “A Good Man Is Hard To Find” may eventually end up murdered by the Misfit, but not before the old lady experiences an epiphany as she stands about to be shot, recognizes her human kinship with this sensitive serial killer, and performs a tender gesture that gets her killed. It is the Misfit himself who famously provides her epitaph and states the moral of the story in his immortal line: “She would of been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life” (Collected Stories 133). We last see her lying in a ditch with her legs crossed under her (an allusion to the crucifix) and her face smiling up at the cloudless sky. The old lady may be destroyed, but she is not defeated. For a Catholic writer, death of the body is not the worst thing that can befall a person. How one dies is what matters.

Another O’Connor story that uncannily connects with Hemingway’s treatment of violence in his fiction is “Greenleaf,” though unlike the bullfight, which Hemingway describes as a tragedy, “Greenleaf” is a comedy in the classic sense of the word. The main character in the story is another garrulous country woman, like the grandmother, who believes she leads an exemplary life but, of course, does anything but.

The main focus of the story is a bull owned by the poor white Greenleaf family who work on Mrs. May’s farm. Due to their laziness and ineptitude (according to Mrs. May’s highly prejudicial view of them), the Greenleafs cannot seem to build a fence or structure that will keep their bull contained, and he wanders onto Mrs. May’s property on several occasions, much to her horror. The bull, throughout the story, is portrayed as a harmless creature who seems to have a strange affection for Mrs. May. In the opening paragraph of the story, he appears outside her bedroom window in the silvery moonlight, munching on her shrubbery, and wearing a hedge-wreath across his horns, like a suitor come to call. As with the bulls in the ritual of the corrida, the bull is imaged as a divine creature, possessed of mythically charged status, both in terms of pagan and Christian mythos.

After several failed efforts to have the bull contained, Mrs. May insists that Mr. Greenleaf shoot the bull, and to make sure the job is done right, she drives her car to the center of the pasture where he is loose to witness the killing. The bull, however, wanders away, and while Mr. Greenleaf goes in search of him and Mrs. May drowses in the warm sun on the hood of her car, waiting for the wayward bull to show, she is suddenly surprised by his appearance:

“Here he is, Mr. Greenleaf!” she called and looked on the other side of the pasture to see if he could be coming out there but he was not in sight. She looked back and saw that the bull, his head lowered, was racing towards her. She remained perfectly still, not in fright, but in a freezing unbelief. She stared at the violent black streak bounding toward her as if she had no sense of distance, as if she could not decide at once what his intention was, and the bull had buried his head in her lap, like a wild tormented lover, before her expression changed. One of his horns sank until it pierced her heart and the other curved around her side and held her in an unbreakable grip. She continued to stare straight ahead but the entire scene in front of her had changed—the tree line was a dark wound in a world that was nothing but sky—and she had the look of a person whose sight has been suddenly restored but who finds the light unbearable (Collected Stories 333).

Mrs. May’s epiphany here is a saving grace, for the bull is, of course, Jesus, who has been wooing her unsuccessfully for some time, mooning about her farm, trying to wake her up to her ugly attitude and behavior towards her fellow human beings. The outcome of this story is shocking, deliberately grotesque, and comic in the classic sense that it depicts a consummation (the story is replete with sexual double entendre) and a happy outcome, spiritually speaking, for Mrs. May. To use Hemingway’s terms, she may be destroyed at the end, but she is not defeated. To use O’Connor’s vocabulary, “She would of been a good woman if it had been a bull to gore her every minute of her life.”

It is also noteworthy here that Mrs. May is described as being “pierced”—that word associated with suffering and with the cross—and that the piercing coincides with a kind or rapture or “ecstasy,” a word whose Greek root means “to stand outside of oneself” and suggests a transcendence of self. O’Connor’s heroine is cast as a modern-day version of Bernini’s St. Teresa in Ecstasy, who is pierced, in the midst of her visionary rapture, by a visiting angel.

Along similar lines, Hemingway associates the violence of the bullring with ecstasy, particularly the faena—the final third of the bullfight wherein the matador performs his capework with the bull before killing him. In Death in the Afternoon he writes of this rapture, describing the faena as a ritual

That takes a man out of himself and makes him feel immortal while it is proceeding, that gives him an ecstasy, that is, while momentary, as profound as any religious ecstasy; moving all the people in the ring together . . . in a growing ecstasy of ordered, formal, passionate, increasing disregard for death (206-207).

The ecstasy O’Connor and Hemingway describe—and that Bernini depicts— is the culmination of intense bodily sensation leading to enlightenment of the soul. The natural leads to the supernatural. Time becomes one with eternity. Suffering is redeemed. It is mystical, transcendent, and deeply Catholic.

The uses of violence by both Hemingway and O’Connor remind us of the reality human life is grounded in: we are all living “on the verge of eternity” (O’Connor, Mystery and Manners, 114), and the way we conduct our lives in the here and now has a spiritual dimension. Violence reminds us of our unceasing proximity to death, and this knowledge can serve as a conduit to grace.

Hemingway succinctly expresses this idea in The Sun Also Rises when his protagonist Jake Barnes tells the hapless Robert Cohn, “Nobody ever lives their life all the way up except bullfighters.” To live fully is to live in the presence of the bull. O’Connor makes a similar statement in one of her essays, only instead of using the image of the bull, she invokes that of the dragon:

St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in instructing catechumens, wrote: “The dragon sits by the side of the road, watching those who pass. Beware lest he devour you. We go to the Father of Souls, but it is necessary to pass by the dragon” (“The Fiction Writer and His Country,” Mystery and Manners, 35)

To live fully, O’Connor argues, is to live in the presence of the dragon, the certain knowledge of one’s own mortality. The bullfighter lives there and so do O’Connor and Hemingway by virtue of their vocation as fiction writers. As O’Connor goes on to say,

No matter what form the dragon may take, it is of this mysterious passage past him, or into his jaws, that stories of any depth will always be concerned to tell, and this being the case, it requires considerable courage at any time, in any country, not to turn away from the storyteller (Ibid., 35).

Hunger for Holiness

It is interesting to note that, despite his reluctance to self-identify as a Catholic writer, O’Connor recognized in Hemingway qualities that marked him as such. In a letter to her spiritual director, Fr. James McCown, SJ, in January of 1956, she writes:

The Catholic fiction writer has very little high-powered “Catholic” fiction to influence him except that written by . . . [Bloy, Bernanos, Mauriac] and Greene. But at some point reading them reaches the place of diminishing returns and you get more benefit from reading someone like Hemingway, where there is apparently a hunger for a Catholic completeness in life . . . It may be a matter of recognizing the Holy Spirit in fiction by the way he chooses to conceal himself (Habit of Being 120).

This hunger for God and for grace haunts Hemingway’s writing. It is no accident that his novels and stories portray his characters as endlessly hungry and thirsty, eating and, especially, drinking, to excess. As Jung once noted, we use the same word for alcohol that we use to describe religious experience: spirit. Drinking is, thus, a manifestation of the desire for spiritual fulfillment.

Both Hemingway and his characters are hungry for holiness, and though they may not know it, he does. It was this hunger that drove him to the Church and to the bull ring. In a letter to Maxwell Perkins, he writes that the bullfight is “the one thing that has, with the exception of the ritual of the church, come down to us intact from the old days” (Letter to Maxell Perkins, February 6, 1926). Both Mass and the Corrida fed his hunger. At the center of each is violent sacrifice. At the center of each is redemption.

From her front porch in rural Georgia, Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor recognized the unlikely kinship she shared with Ernest Hemingway, the most celebrated secular writer of her day. She knew that the Church is large—that it contains multitudes (to paraphrase the anti-Catholic Walt Whitman)—and that there are more ways to be a Catholic writer than are dreamt of in most readers’ philosophies.