If we think of a large Asian country where religion is the center of daily and political life we might think of India or Indonesia. But China? If we have associations of religion and China it might be historical: ancient classics like the Daodejing, great Buddhist art along the Silk Road, the Nestorian stele outside Xi'an, or Matteo Ricci's grave in Beijing.

As for contemporary Chinese religious life it is probably linked in our mind to Communism, which we think of as atheistic and intolerant of religion. Thus, we might think about persecution: Christians meeting in underground churches, the Dalai Lama in exile, or sects like Falun Gong being banned. This might be reinforced by governmental or non-governmental reports that paint a bleak picture of religious life in China.

None of this is wrong. Especially now, under Chinese leader Xi Jinping, some faiths are struggling, especially Islam and Christianity. Muslims have been interned in Xinjiang and churches closed or even torn down. It is clear that for some religions, these are challenging times—maybe the most challenging in a generation.

But one reason for this is that China is in the midst of an unprecedented religious revival, involving hundreds of millions of people—best estimates put the figure at 300 million: 10 million Catholics, 20 million Muslims, 60 million Protestants, and up to 200 million followers of Buddhism, Taoism, and folk religions. This does not include the tens or even hundreds of millions of people who practice physical cultivation like Qigong or other forms of meditative-like practices.

The precise figures are often debated, but even a casual visitor to China cannot miss the signs: new churches dotting the countryside, temples being rebuilt or massively expanded, and new government policies that encourage traditional values. Progress is not linear—churches are demolished, temples run for tourism, and debates about morality manipulated for political gain—but the overall direction is clear. Faith and values are returning to the center of a national discussion over how to organize Chinese life.

+

What drives this growth? I would argue that hundreds of millions of Chinese are consumed with doubt about their society and turning to religion and faith for answers that they do not find in the radically secular world constructed around them. They wonder what more there is to life than materialism and what makes a good life. As one Protestant pastor told me, “We thought we were unhappy because we were poor. But now a lot of us aren’t poor anymore, and yet we’re still unhappy. We realize there’s something missing and that’s a spiritual life.”

Most surprisingly, this quest is centered on China’s heartland: a huge swath of land running roughly from Beijing in the north to Hong Kong in the south, Shanghai in the east to Chengdu in the west. This used to be called “China proper” and for 25 centuries has been the center of Chinese culture and civilization, the birthplace of its poets and prophets, the scene of its most famous wars and coups, the setting for its novels and plays, the home of its holiest mountains and most sacred temples. This is where Chinese civilization was born and flourished, and this is where the country’s economic and political life is still focused.

We have long known that China’s ethnic minorities—especially the Tibetans and Uighurs—have valued religion, sometimes as a form of resistance against an oppressive state. But now we find a similar or even greater spiritual thirst among the ethnic Chinese, who make up 91% of the country’s population. Instead of being a salve for China’s marginal people, it is a quest for meaning among those who have benefited most from China’s economic takeoff.

Not all Chinese see their country's national malaise in spiritual terms. Government critics often view it as purely political: the country needs better rules and laws to solve society’s ills. Reformers inside the system see it more technocratically: if they had better administrative structures and provided better services, apathy and anger would abate.

But most Chinese look at the problem more broadly. China needs better laws and institutions, yes, but it also needs a moral compass. This longing for moral certitude is especially strong in China due to its history and tradition.

For millennia, Chinese society was held together by the idea that laws alone cannot keep people together. Instead, philosophers like Confucius argued that society also needed shared values. Most Chinese still hold this view. For many, the answer is to engage in some form of spiritual practice: a religion, a way of life, a form of moral cultivation—things that will make their lives more meaningful and help change society.

All told, it is hardly an exaggeration to say China is undergoing a spiritual revival similar to the Great Awakening in the United States in the 19th century. Now, just like a century and a half ago, a country on the move is unsettled by great social and economic change. People have been thrust into new, alienating cities where they have no friends and no circle of support. Religion and faith offer ways of looking at age-old questions that all people, everywhere, struggle to answer: Why are we here? What really makes us happy? How do we achieve contentment as individuals, as a community, as a nation? What is our soul?

+

How did China get to this situation? To understand we have to back up to the mid-19th century. China went through a series of crises that were paralleled around the world. This was the encounter with the West, and its far superior military and technological power. China lost a series of wars that saw it lose territory. Chinese looked around the world and saw how the West had carved up most of the globe into colonies. Even ancient lands like India were controlled by tiny western countries like Britain. Would China be next?

Thus began an assault on the existing power structure—which meant the political-religious state that ran China. Why religion? Couldn't China have modernized without attacking traditional religions? To understand why religion became a problem for China's modernizers, we have to understand the central importance of religion in traditional Chinese life.

Today many of us are used to thinking of religion as one part of society, perhaps a pillar, but discrete and not dominating. But in most traditional societies this was not how society was organized. Religion was central to life. It was involved not only in a narrowly defined “spiritual pursuit” of transcendental issues, but in how people lived their lives—from the location and orientation of their dwellings to their professions.

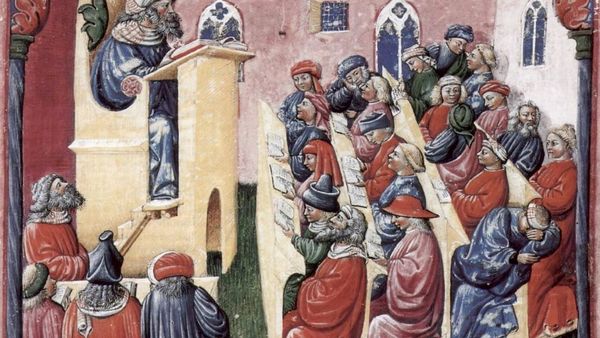

In China, this was also the case. Religion was part of belonging to your community. A village had its temples, its gods, and they were honored on certain holy days. Choice was not really a factor. China did have three separate teachings, or jiao—Confucianism (rujiao), Buddhism (fojiao), and Taoism (daojiao)—but they did not function as separate institutions with their own followers. Primarily, they provided services: a community might invite a priest or monk to perform rituals at temples, for example, and each of the three offered its own special techniques—Buddhist Chan meditation or devotional Pure Land spiritual exercises, Daoist meditative exercises, or Confucian moral self-cultivation. But they were not considered separate. For most of Chinese history, people believed in an amalgam of these faiths that is best described as “Chinese Religion.”

This faith extended to politics as well—so much so that scholars like John Lagerwey speak of China having been run by a “political-religious state.” The emperor was the "son of heaven." His officials legitimated their positions through religious rituals at local temples. And at the very local level—where life was actually lived—the world revolved around temples. This was where the local gentry, or literati, met and organized local life, from irrigation and road-building to raising militias. Thus the historian Prasenjit Duara calls temples a “nexus of power” in traditional China.

So, when revolutionaries wanted to change China, they went after power where it lay: in this political-religious system that ran the empire. A telling example involves Sun Yat-sen, who would eventually help overthrow the Qing dynasty and establish the Republic of China in 1912. One of his first acts of rebellion as a young man was to go to the local temple in his hometown and smash its statues.

What of the monotheistic faiths? Islam entered China more than a millennium ago via traders along its coast and up through the Grand Canal to Beijing, as well as along the Silk Road from Central Asia. But Islam was mainly confined to China’s geographic periphery, including regions like Xinjiang, Gansu, and Ningxia that were only occasionally under Chinese control. Even today, with these regions firmly ruled by Beijing, Islam counts at most 23 million believers, or 1.6% of the population. Conversions almost only happen when people marry into Muslim families—a result of government policies to define Islam as a faith that is practiced by only ten non-Chinese ethnic groups, especially the Hui and Uighurs. Islam sometimes provides an identity for people who do not want to be ruled by China—a situation we find today among the Uighurs in China’s far western province of Xinjiang—but its marginalized position means it rarely enters the contemporary national debate on faith, values, or national identity.

The impact of Christianity was radically different. It entered China later but spread among Han Chinese, causing much angst around the turn of the century. One popular saying then was “One more Christian; one less Chinese” (duo yige jidutu; shao yige zhongguoren)—the idea was that the religion was incompatible with being Chinese. But its influence was huge, helping to define modern China’s religious world. One basic reason for Christianity’s influence was its presence in the West. Chinese reformers realized that Western countries were Christian and concluded that it was not incompatible with a modern state. Some, like the Nationalist Party leader Chiang Kai-shek, even converted.

But more influential was the decision by almost all modernizers of China to adopt the western distinction between religion and superstition. The paradigm to determine acceptable from inacceptable practices was imported from the West via Japan, which had started a similar discussion a generation earlier. Chinese tinkers imported words like zongjiao (religion) and mixin (superstition).

The new way of organizing society called for the compartmentalization of religion, much as it had been in other societies. For much of European history, for example, politics and religion were closely intertwined. The rise of the nation-state in the 17th century began to change this, diminishing and compartmentalizing religion. The bureaucratic state took over schools and hospitals and destroyed legal privileges enjoyed by the church. The rise of Protestantism played an important role too, with the binary terms of authentic “religion” and taboo “superstitions” used to try to discredit some Catholic practices. This fed into Christianity’s long-standing appeal to logic: true religion could be defended by reason; everything else was superstition and should be destroyed.

As the world globalized in the 19th and 20th centuries, these ideas spread. When the Ottoman Empire collapsed after World War I, the new Turkish state abolished the caliphate—the ruler of all Muslims—and even converted some mosques into museums. In the Middle East after World War II, political movements like the Ba’ath Party in Iraq and Syria tried to scale back Islam as well, seeing it as a cause for their region’s colonization by the British and French. All these movements were united by one desire: a strong state to imitate and fend off Western countries.

In China, this movement gained ground as revolutionaries like Sun gained ground in the late 19th century. At that time, China had an estimated one million temples around the turn of the century. A movement for political reform in 1898 called for many temples to be converted to schools. Although this reform plan was defeated, many local governments took steps on their own, and today many of the best-known elementary and high schools across China are located on the grounds of former temples.

Some traditional faiths survived. Out of the old amalgam of Chinese beliefs, Buddhism and Taoism coalesced into organized religions with organized hierarchies—something they did not have previously. Buddhism responded best to the new times. In the last dynasty, the Qing, it had already held a privileged position in society because the ruling family were ethnic Manchurians, who worshipped a form of Buddhism. It had a better-educated clergy that could interact with the new bureaucratic state being constructed by the Nationalist (and later the Communist) state. Early 20th century Buddhist thinkers came up with the idea of “Humanistic Buddhism”(renjian fojiao), the idea being that Buddhism should be part of the here and now, dealing with problems in society, and not only concerned with otherworldly affairs.

But most Chinese religion did not fare so well. Confucianism had been too closely tied to the old system to survive easily, despite efforts in the early part of the century to organize it into a religion, or even to declare it China’s “national” religion, much as Japanese reformers had done with indigenous religious practices that became known as Shinto. As for Daoism, it survived, but only barely. Because it was less hierarchical than Buddhism, most of its temples were not organized and ended up being closed or destroyed, leaving just a few of the great monasteries in the countryside or remote mountains.

Most tragically, folk religion was all but wiped out. These were the innumerable small temples or shrines that were locally managed and not linked to the major faiths—in other words, the vast majority of temples in China. They were declared “superstitious.” Hundreds of thousands of temples were obliterated, an immense wave of auto-cultural genocide.

When Sun’s Nationalist Party took power, the pace picked up. Sun's successor, Chiang Kai-shek, launched the “New Life” movement to cleanse China of old ways of doing things. Along with trying to eradicate opium, gambling, prostitution, and illiteracy, the Nationalists launched a campaign to destroy superstition as part of a broader effort to jianguo, or create a nation. In a precursor of Mao’s Red Guards, Nationalist Party youth organizations sent groups out to destroy traditional temples, and the government issued regulations with the ominous name “Standards to Determine Temples to Be Destroyed and Maintained.” The Nationalists effectively controlled China for only 10 years, so the impact of their measures was limited, but the course was set: Chinese religion was a social ill that needed to be radically reformed or destroyed in order to save China.

This way of looking at religion—as a problem that had to be controlled for China to resume its place as a great power—was picked up by the Communists, when they took power in 1949. More organized and possessing a powerful bureaucracy led by a Leninist political structure, they treated religion as one among many social groups to control. As in the beginning of the Republican era, only five religious groups were registered with the central government: Buddhism, Daoism, Islam and Christianity, which for administrative purposes was divided into two: Catholicism and Protestantism.

These five groups were run by groups under Communist Party control. But this system only lasted a few years. By the late 1950s, China was being run by increasingly erratic radical policies, culminating in the Cultural Revolution that banned all open religious expression.

When the Cultural Revolution ended with Mao's death in 1976, the Communist Party began to revise its position. Bereft of allies in society, it allowed all five religious groups to return. They rebuilt churches, mosques, and temples. They retrained clergy. The five official religious organizations were reinstalled. In Christianity, underground congregations existed but were explicitly tolerated.

This does not mean that China enjoyed religious freedom. Over the next 30 or so years, persecution continued—underground communities were attacked, the Dalai Lama's faction was still ostracized, while new religious movements like Falun Gong were attacked. But by and large the government was neutral. Religion was viewed skeptically but its growth was tolerated. By and large the government allowed religious groups to multiply—and they did, with churches, temples, and mosques sprouting up across the country.

+

For about the past decade, however, we have been in a new era. It is easy to peg this to Xi Jinping's assumption of power in 2012 but I believe it began earlier, around 2008.

This was one of those epochal years in China when history seemed to turn. The great Beichuan earthquake killed 69,000 people and spurred an outpouring of civil society activity. Led by Christian groups, people journeyed to Sichuan to donate food, water, and blankets. Some began to investigate why so many schools collapsed.

Out of this came two distinct trends: charitable donations that were encouraged by the government, and activists, some faith-based, who wanted to find the deeper reason for the tragedy. Most of the religious groups were soon sent home. The government eventually passed a law allowing charitable giving, including from faith-based communities, but discouraged civic engagement.

Around the same time, the government began to encourage “intangible cultural heritage,” a term borrowed from UNESCO to mean practices, such as music, rituals, drama, and song—things that were deserving of protection but could not be felt and seen, as the Great Wall might be.

In practice, this meant rehabilitating many things that previously had been attacked as superstitious. Hence rituals, and even traditional folk religious pilgrimages were redefined as cultural practices worth preserving and even subsidizing.

As a strong leader with more levers of power than his predecessor, Xi has increased the pace of this tilt toward traditional faiths. Early on he visited Confucius's hometown of Qufu and praised the sage. During a visit to UNESCO in 2013 he praised Buddhism, saying it had contributed mightily to China after it had indigenized several hundred years ago. He also increased money for intangible cultural heritage, so much so that China now has more than 12,000 practices, many of them with a spiritual orientation, that the government actively subsidizes.

Xi also meets regularly with religious leaders in a way his predecessors did not. He has met four times with the Taiwanese Buddhist abbot Xing Yun of the Fo Guang Shan Buddhist missionary movement, and allowed the organization to set up offices in China to promote the faith.

In some ways, we can see in Xi's actions the recreation of the old political-religious state that ran China. But instead of religion truly being imbued in the state, it is more of a tool used to legitimize authoritarian rule. In some ways this is a familiar scenario: many rulers turn to religion when their own ideology becomes bankrupt. Thus we see, for example, the ex-KGB officer Vladimir Putin adopting the mantle of defender of the Orthodox faith, or in earlier years dictators like Saddam Hussein turning into devout Muslims.

+

But not all religions benefit from the state's new patronage. While Buddhism, Daoism, and folk religion are being explicitly supported for the first time in a century, Islam and Christianity are on the defensive. Both are seen as violating a primary taboo in Chinese society: possessing foreign ties. Of course, all religions have a foreign component. Even Daoism, China's only indigenous faith, has ties to believers in Sinophone communities around the world, many of which—especially in Southeast Asia—helped rebuild Daoist temples after the Cultural Revolution. And Buddhism, too, has believers in other countries, not to mention the exiled spiritual leader the Dalai Lama. By and large, however, the government feels it can contain these foreign links and that they are outweighed by the benefit that sponsoring these faiths have to the Communist Party's legitimacy. The Abrahamic faiths, however, are still viewed as foreign faiths that have inadequately Sinicized, and the government has recently adopted new regulations to enforce its new policies.

Coming in for the harshest treatment has been Islam. Although only 20 million people in China—less than 2% of the population—are believers, many are located in strategic border regions, such as Xinjiang in Central Asia. There, the state's heavy hand has led to an independence movement among the Uighur ethnic minority, some of whose followers see in Islam a way to push for a separate identity.

The government sees it primarily as a law-and-order issue that the state can handle with violent repression. The state has set up reeducation camps in Xinjiang, for example, with up to 1 million Uighurs having been held. The government says that these are simply job training centers, but no independent scholar or expert—Chinese or foreign—sees it as such. Instead, these are clearly ways to force secularize Muslims, by discouraging them from avoiding pork and alcohol, and forcing them to read government propaganda.

These tactics are bound to backfire because the aspirations for autonomy and equality is legitimate. The state's response will probably only lead to more violence. But from the government's point of view Islam is a faith that can be controlled by isolation and repression. It is seen as a police problem, hence the government's constant refrain that it is a victim of global Islamist terrorism.

Not so Christianity, which arguably is a more profound challenge to the government's effort at constructing a new spiritual world. Islam is limited to ethnic minorities and has little appeal to the Han majority—conversions are almost nil—but Christianity appeals to China's Han majority. Without stretching too much, one can say that Christianity is the first major religion to find a permanent foothold among the Han majority since Buddhism arrival two millennia ago.

Just as with Islam, the government appears to be increasingly skeptical about Christianity, mirroring a series of actions against the faith. From 2014 to 2016, the government forcibly removed crosses atop more than 1,500 churches in the province of Zhejiang. This proved to be a precursor to a series of steps against other churches, including three of the best-known Protestant underground churches in China: the Zion church in Beijing, the Ronguili church in Guangzhou and the Early Rain church in Chengdu.

And then there are government efforts to span Protestantism and Catholicism: blanket coverage of churches and pilgrimage sites with closed-circuit television cameras, something also found at mosques but not at Buddhist or Daoist temples (although it is quite possible that they will eventually have this too, given the government's determination to blanket the country with cameras, but the decision to first cover churches and mosques feels significant).

Most striking are new regulations calling on all religions to "Sinicize," which I can only interpret as meaning being closely under party control. This rule applies to all religions—hence the sometimes-absurd situation of Daoist temples holding “study sessions” to promote their Sinification—but I think Christianity is at the center of this because it is the Christians who have the biggest and most vibrant underground churches. Clearly the message is that these underground churches must join the official church. The methods are different.

If the closure of the big Protestant churches can be seen as a shot across the bow, the government's policy toward Catholicism is different: diplomacy. Last year, Beijing and the Vatican struck an accord that would allow the two sides to jointly appoint bishops.

This deal is not without advantages for Catholics, and should not immediately be written off as a naïve effort by Rome that plays into the hands of the party. According to reliable demographic studies, the number of Catholics in China is at best stagnant, and quite possibly falling. This is partly because Catholicism, for historic reasons, is rural based, but rural China is emptying out as the country goes through an unprecedented urbanization. Its clergy, however, is divided between above- and under-ground, making it not able to respond effectively to this challenge. In short, mission work has faltered. So from the Vatican's point of view, a deal with China could make sense if it revives the Church's structure in China and allows it to more effectively provide pastoral work.

Unfortunately, this is diametrically opposed to the Chinese government's goals, which is to better control Christianity. How this plays itself out cannot be known, but it is clear that an invigorated Church is not Beijing's goal. Instead it wants to make the underground Catholic church irrelevant, and forcing all Catholic to worship in government-approved churches.

+

If we take all these strands together, the most important conclusion is that religion, far from being an issue of fringe or esoteric interest, is back in the center of Chinese politics. This is the result of hundreds of millions of worshippers pushing for a place in society. And now, because they have not died out but instead proven to be an irreplaceable part of modern-day, the Communist Party has decided to try to coopt some of this new social force, creating opportunities but also growing tensions.

For millennia, religion was the ballast that kept the Chinese state stable. For over a century, the state cast it overboard and Chinese society heaved to and fro, swinging from dictator-worship to unbridled capitalism. Now, religion is back but the question is if it will be a stabilizing force in society, or unmoored by counterproductive government policies, a loose cannon that crashes through the decks.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This article was adapted from an essay that originally appeared in Religion and Christianity in Today's China.