One does not usually think to find a Catholic mystic in a mid-twentieth century lay woman who emerged from the rubble of post-war bombardment. Chiara Lubich’s native city of Trent suffered eighty incursions by the Allied troops between 1943-45, with a total of 400 fatalities and 1,792 injured. The Lubich home was rendered completely uninhabitable. The end of the war also meant the end of Fascism, but the way forward for the people who suffered under this authoritarian regime still needed to be charted. Igino Giordani, who Lubich later would call her “co-founder” of the Focolare Movement, arranged for the release from prison by Mussolini of the Tridentine Social Democrat and later Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi. The reconstruction of life and society after Fascist repression and a bloody Nazi occupation was slow and filled with concerns that might have appeared more pressing than devotion to one’s spiritual life. Yet the illumination of her mystical vision known as “Paradise ’49” began precisely in this milieu.[1]

Moreover, the war had shattered the illusion of a God who aided in the divisive expansion of either fascist or socialist might. Chiara Lubich was not seeking a balm from God that would free her and her companions from the misery and confusion they now faced. She and her companion “Foco” (Igino Giordani) opened their hearts to a God who could make sense of the rubble well aware that Jesus Christ had emptied himself on a cross and thereby entered into the midst of human fragility. When the thirty-four-year-old French philosopher and exiled Vichy opponent Simone Weil redacted The Need for Roots in 1943, she too realized that the needs of the vanquished and spiritually arid soul could not be a mere addendum to post-war reconstruction. Jesus was in the midst of the community of Chiara and her companions, huddled together in their Mount Tabor in the Dolomites, to help them build new “edifices” out of the rubble for the soul and for society.

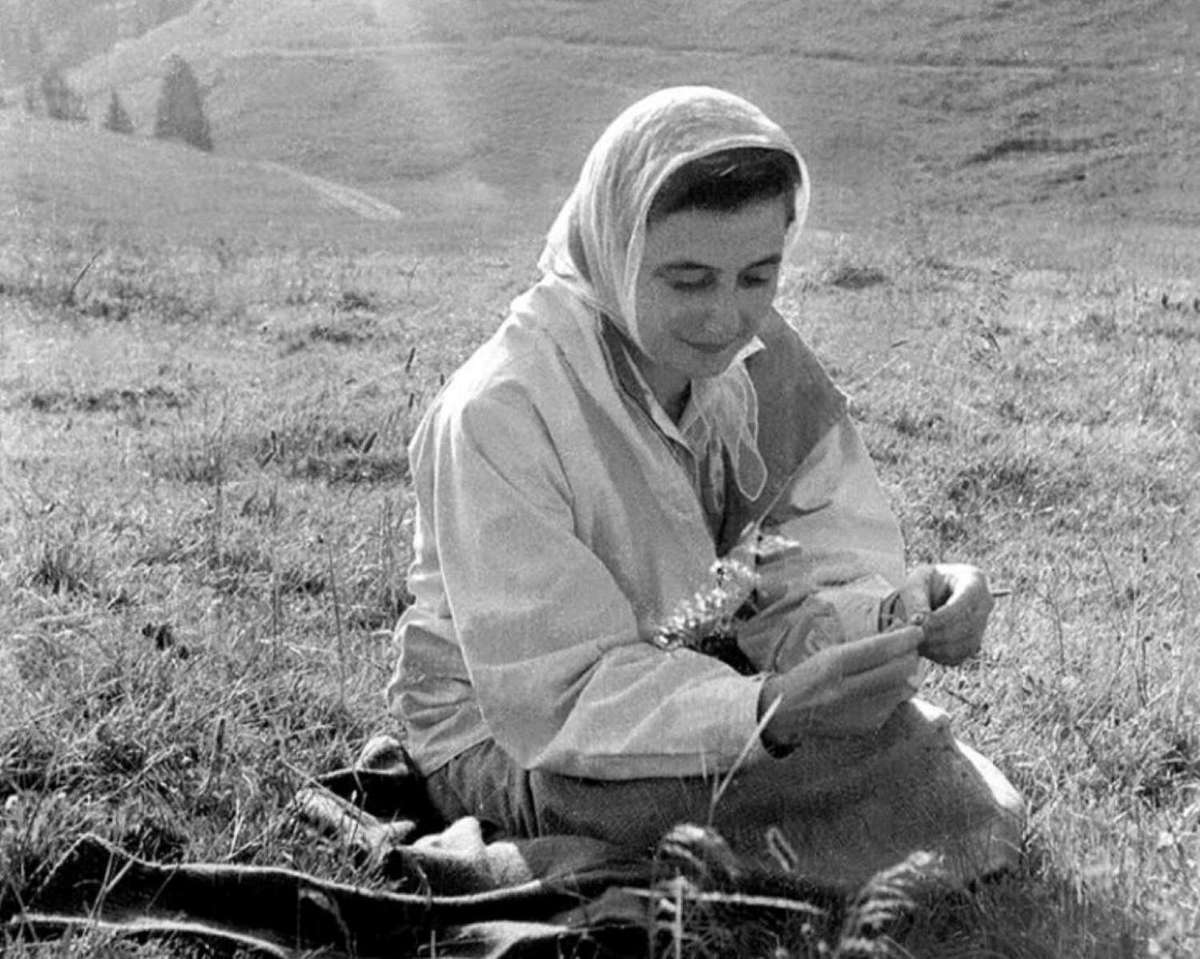

Chiara Lubich eventually came down from the mountain and began life anew. Chiara was certainly an itinerant mystic on fire with the love of God and no less eager to transmit that illumination to others who joined her on this path. She recounts that she never experienced a blinding vision or a fall from a horse. Her mystical experience was “a sweet engrafting,” an experience of the unitive presence of Divine Love. The dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio’s Calling of St. Matthew was replaced by the quiet still life with her eight companions that transpired in a mountain cabin that was little more than a cowshed. The everydayness of this scene is deceptive. God was working through her de arriba (“from above”), in the words of St. Ignatius of Loyola, but the effects of God’s work were palpably evident on the ground and in the midst of the humble women who were sharing their lives and scarce material goods together.

Chiara also narrates an experience of beauty. The environment of the Dolomites contributes a natural beauty, but she was responding to a divine beauty that was, in the words of St. Augustine, both ancient and new. Why is hearkening to divine beauty so urgent and important in our day and especially in the midst of the manifold social and political problems that beset our world? In Called to Attraction: An Introduction to the Theology of Beauty, theologian Brendan Sammon has written about the relevance today of being called to the attractiveness of God. Young adults are often just as befuddled by the numbing indifference of the world to faith as by the opponents of the Church. They need to be awakened by the power of God’s beauty and the beauty that irradiates from the lives of holy women and men. Even more concretely, the mosaicist Marko Ivan Rupnik has argued convincingly through his work In the Fire of the Burning Bush: An Initiation to the Spiritual Life that the vocation to beauty and the new evangelization go hand in hand. Such beauty is never sanitized or precious. Beauty is the irruption of an unforeseen reality that beckons a call to a new way of life. Beauty penetrates the core of a person and unifies the forces of creative energy that must be harnessed if one wishes to face the harsh realities of life.

From the outset, Chiara Lubich pursued a mysticism that was firmly in the Church. This included but went beyond the sacramental life. The ecclesial dimension of her mysticism was a function of the communal relationship with Christ. The mystical marriage that she undertook in the wake of her pact with Foco was unique. It was not between her individual soul and God, as in the much-revered traditional female spirituality of the Middle Ages. But it was also not a union between a social body and a non-localizable and utopian Absolute Spirit, as in the ideology of secular progress. In the concrete place of the Father’s bosom, Chiara saw one Soul that embraced the “we” of her own soul and that of her companions. Seen from the vantage point of paradise, God’s own unfathomable love was now da noi, dwelling among us and beckoning us to greater discipleship.

Gerard Rossé has written elegantly about how the ecclesial origins of Focolare can be likened to the Church in the Letter to the Ephesians. Chiara does not just interpret the ecclesiology of Ephesians. She shows her companions how daily life can be lived in imitation of the revelation of the divine love in the Word of God. St. Thomas Aquinas had a similar inspiration regarding the catechetical pedagogy of communicating the eternity of paradise into the midst of time (See: ST II-II, 171, 6c). Regarding the unity encountered in the body of Christ, Aquinas exegetes Ephesians 4:15-6 as follows:

A connecting and binding force emanates from Christ, the head, into his body, the Church, since whatever is united must be held together or bound by some nexus or bond. On this account he says fitly joined together, by what every joint supplieth, that is, through the faith and charity which unite and knit the members of the mystical body to one another for their mutual support. “All the works of the Lord are good: and he will furnish every work in due time” (Eccles. 39:39). Thus, the Apostle himself, confident of this mutual being-of-service (mutua subadministratione) which reigns among the members of the Church due to the divine unifying action, had said: “I know that this shall happen to me unto salvation, through your prayer and the assistance of the Spirit of Jesus Christ” (Phil. 1:19).[2]

Chiara too sees faith combined with charity infusing the members with a new spirit of unity. Her ethics of Paschal unity and spirituality of communion have vast repercussions for how we can think about the field hospital of the Church in itself and in its service to the woundedness of the world.

Accordingly, she also connects this unity of Agape-Love to Jesus Crucified and Forsaken. Chiara and Foco had a vocation to make their own the experience of Jesus’s forsakenness. As she recalled saying to Foco at that time:

Look, it might be that what you feel is really from God. But not two one, all one. But it may really be that it is from God so we shouldn’t waste it . . . You know my life, it is to be nothing, because I live Jesus Forsaken, and so I exist if I am nothing. He is everything, I am the nothingness. So, if I want to be what I truly am, I have to be nothing, and in this way I exist. And you are nothing, because you too are Jesus Forsaken. We have to live this nothingness. If we are this nothingness, then we are what we are, because we put ourselves in our true being. As Saint Catherine said: ‘I am nothing, you are Everything.

Il nulla (“nothingness”) is not a mere metaphor; it is a form of existence. How can we exist seeking to share in the fullness of life if we are called to imitate Christ’s self-emptying to the utmost? There are implications here that extend far beyond a secure spirituality for the most dedicated of Christians. It is the adventure that remains attentive to God’s presence and absence in multiple contexts and sets of beliefs. Through communion with “her Almighty Spouse” the sin and even “the hell” that Christ undergoes is made her own.[3] When humanity experiences God in God’s absence, the heart that is wedded to the Forsaken One embraces this very emptiness out of a firm faith in his being resurrected on the third day.

Chiara’s spirituality of an “exterior castle” is also a vision for humanity.[4] Others have recognized its breadth of application to contemporary life. In 1977, for example, she was awarded in London a Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion. In the context of this translation of her founding experience into English, it is interesting to reflect on her experiences of entering, like Mother Cabrini (whose actual tomb she visited in 1997) arriving from a distant shore, the “castle” of these shores. According to Donald W. Mitchell, Chiara made seven trips to the United States:

1964: First trip to USA to visit the Focolare in New York City.

1965: Visit to New York City and founding of New City Press.

1966: At invitation of Cardinal Richard Cushing, she founded the Focolare in Boston.

1968: Visit to New York and inauguration of the Mariapolis Center in Chicago.

1990: Visit to Mariapolis Luminosa in Hyde Park New York, one of thirty-two “little cities” operated by the Focolare around the world.

1997: Received Honorary Degree in Humane Letters from Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut and made a presentation at Malcolm Shabazz Mosque in Harlem.

2000: Received Honorary Doctorate in Education from Catholic University of America, and went with W.D. Muhammad to the “Faith Community Together” event at the Washington DC Conference Center with Focolare members and with African American Muslims.

Each of these engagements pointed to the building up of a new civilization on the North American landscape. She knew that practical culture wanted concrete answers to the problems people face. The experience of the Dolomites was not meant to be replicated in the Hudson River Valley of the state of New York or anywhere else that she visited. From the challenges of race relations and religious pluralism to the invigoration of the Christian’s task of education, Chiara was prepared to share her gift from the triune God with peoples of many lands, including here in the United States. The Focolarine and Focolarini in the United States represent not only a culturally diverse communion spread throughout many regions of this land endowed with diverse professional talents. More importantly, they are the recipients of the gift of Chiara’s seven initiatives on U.S. soil to build a new culture of encounter in ecclesial settings and beyond.

The pact that Chiara made in 1949 with Foco had no marketing plan. It transpired in its own distinct socio-political milieu but was never intended to spread the social Gospel of De Gasperi’s Christian Democracy throughout the globe.[5] It was a pact with the Trinity that was designed to let the fruits of their new life grow organically in new and hitherto unexplored fields. The readers of the collection Paradise: Reflections on Chiara Lubich's Mystical Journey will thus be astonished at the newness of Chiara’s experience. Chiara even writes about her mystical experience as a revolution:

It is necessary to make God be reborn in us, to keep him alive and make him overflow onto others as torrents of Life and resurrect the dead. And keep him alive among us by loving one another . . . Then everything is revolutionized: politics and art, school and religion, private life and entertainment. Everything.

No sphere of existence is excluded. The nurturing of an inner flame expands from the interior castle to an exterior one. From that socially inclusive but spiritually well-fortified rampart, even politics and economics need to be assessed in a new light. Her social vision recapitulates an insight that G. K. Chesterton once made with regard to the social vision of Charles Dickens. The novels of Dickens, Chesterton said, reclaimed the forgotten third ideal that was used by Robespierre as a rallying cry after the French Revolution, namely, the principle of fraternity.

What does fraternity look like in the Americas today and how is it linked to the original experience of 1949? Chilean social scientists Rodrigo Mardones and Alejandra Marinovic have argued that fraternity has a suppressed but nonetheless identifiable semantic domain in the North American socio-political consciousness. This hidden undercurrent in North American politics represents both a more subtle and a more viable political theory than a poorly defined communitarianism. This impetus for a new ethos of political unity thus merits a great deal of further study. A small band of women were the nucleus, to which Chiara added the pact with Foco.

The Focolare thus included a complementarity of the Marian and Petrine profiles virtually from its very founding. Mardones and Marinovic remind us that the sociologist and jurist Georges Gurvitch long ago defended fraternity in the domain of law to show that there is a legal foundation for criticizing the juridical rights only of an isolated individual and that feminists have put forwarded the notion of civic friendship (solidarity between women and between women and men) as an alternative to the male-dominated discourse that inevitably accompanies the English word “fraternity.” The Jewish philosopher Emanuel Levinas likewise argues in Totality and Infinity that fraternity is not just a biological reality like filiality but a genuine social fruit of an ethical monotheism. For Levinas intersubjective encounters between strangers that are dialogical and thus genuinely fraternal are one primary alternative to monolithic totalities, but he controversially claims that such fraternal bonds only flow out of the monotheistic view of human kinship standing before God not from a merely secular ethic. Levinas also reminds us that the Good Samaritan is a prime Biblical example of the politics of fraternity. These starting points for a new politics of fraternity could certainly be explored further in the light of the unique encounter with God in Paradise ’49 that Chiara extended as an offering both to the members of Focolare and to the world.

Paradise ’49 also has significance for dialogues with Buddhism, Gulen, and non-Western religious traditions. The Focolarini who participated in these encounters are offering a homecoming to the adherents of non-Christian traditions. Far from proselytizing, these are opportunities to transform the gift of love into a dialogue.[6] As Donald Mitchell notes, Chiara’s search for the right balance between personal and communal experiences of the fruits of contemplation can find unexpected echoes in other traditions. The barriers between religions easily become social barriers, even where violence in the name of God has never been an issue. Chiara’s dialogical, agapic-kenotic method has attracted admirers because of its insights into the unique form of human relationality that results from a commitment to transcendence in our fast-paced and atomizing world. These encounters have engendered both religious and social bonds that are especially important in the face of the present and future crises that we face and will face as a planet. Likewise, the Holy Father in an Urbi et Orbi message during the Easter season of 2020 asked Catholics around the world to promote “a contagion of hope” in the midst of the global pandemic caused by the coronavirus.

The international headquarters for Chiara’s ecclesial movement is located in the Diocese of Frascati, and Chiara’s tomb can also be found there in the Focolare’s International Center (together with the tombs of the original companions Igino Giordani and Pasquale Foresi). The first phase of the beatification process of servant of God Chiara Lubich was completed in November of 2019 by the local ordinary, Bishop Raffaello Martinelli. The devotion to her continues today with pilgrimages to the tomb, but her spirituality of unity goes far beyond the ecclesial movement that she founded. It is a gift for the Church and for the world.

The overwhelming illumination given by divine beauty that first irradiated itself in the midst of rubble is now refracted through many lenses on every continent. The reports in the pages of Paradise: Reflections on Chiara Lubich's Mystical Journey testify to the hope that this light is engendering in our world today. The remarkable fact is not the vision’s vastness but its continuity with the origins. Jesus in his forsakenness gives birth to a new unity that is received through the Spirit from within the bosom of the Father. The Mount Tabor of the Dolomites was the original source of this espousal to the Word and the communal activity of witnessing that it generated. This volume makes it possible to explore the Trinitarian spirituality of Paradise ’49 in a new and exciting way. It will surely contribute to spreading the contagion of hope proclaimed by Pope Francis.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is an excerpt from Paradise: Reflections on Chiara Lubich's Mystical Journey. It is reprinted here by courtesy of the New City Press, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

[2] St. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on St. Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians (Albany, N.Y.: Magi Books, 1966).

[3] Chiara Lubich, The Cry of Jesus Crucified and Forsaken (New York: New City, 2001), 62.

[4] On this point, see, for example, Piero Coda, From the Trinity.

[5] Chiara Lubich, Essential Writings: Spirituality, Dialogue, and Culture (New York: New City, 2007), 238.

[6] Donald Mitchell, “The Mystical Theology of Chiara Lubich: A Foundation for Dialogue in East Asia,” Claritas 3,2 (October 2014): 45.