For as long as I can remember, I have been preoccupied with the question of Woman. Who is she? What is her significance? What stories are told about her? What stories does she tell? What is her place—and thus my place—in the world, and before God? What is this meaning of the body I am? If indeed such things are charged with meaning.

I grew up in an Evangelical context that gave few answers to such questions. This was a kind of Christianity shorn of anything visibly female. There was some interest in femininity, narrowly construed, but only in the outskirts of things, never in the sanctuary—kitchens, nurseries, and women’s Bible studies. But there was no Mary, except for a brief cameo at Christmas. No Church as our Mother, no communion of saints. No Hildegard, no Joan, no Judith, sword drawn.

I did have Jezebel, of course, and Esther, Deborah, and Hannah. My namesake, Abigail. I devoured these old and otherworldly stories, and turned also to other books. Alice on the other side of the looking glass, Lucy and Jill in the wilds of Narnia, and all those bloody pages of grim fairy tales. I sought after her—woman—in worlds full of danger and magic, nightmares and bliss—where things that are not supposed to speak said beautiful and unsettling things.

There was one book—The Farthest Away Mountain—about a young girl who was thrust into adventure by a mountain that called her by name, nodding its great head. That is what I wanted—a mountain that spoke and beckoned, calling me out of an ordinary world into something new and strange.

I could find it in glimpses here and there, in these childish, magical books, but I had to learn to do without it in the “real world” as I went into high school and college, and began to read grown-up things. Things like feminist literary theory! I followed the question of woman there, and it was invigorating, although I quickly learned to equivocate. I could still look for woman, and read about woman, and write about woman, as long as I conceded that “woman” did not really exist, at least not in any essential or intrinsically meaningful way. One can speak about women perhaps, but not about Woman.

This seemed to be, primarily, a feature of Anglo-American feminism—perhaps because of those Protestant roots, an enduring uneasiness with the female embodiment. “Who shall measure,” asks Virginia Woolf, “the heat and violence of the poet’s heart when caught and tangled in a woman’s body!” French feminist literary theory was another story. Here, the female body loomed large. Here was a different kind of strangeness—drives, and fluids, and jouissance. Writing as giving birth. Writing with milky white ink. Here, at last, something that is not supposed to speak—the female body—was allowed to say beautiful and unsettling things.

In graduate school, I wanted to see how women novelists were answering this question: who is woman before God? What is her spiritual meaning? The work of French feminist Luce Irigaray became my primary theoretical lens. This is her contention, in brief: “Woman” has not been truly represented in literature, theology, or thought because she is defined oppositionally through Man. We must, she contends, take sexuate identity and difference seriously; we must begin to think in terms of “two” subjects, rather than one masculine subject. To paraphrase in my own terms: we must begin to think more in terms of Genesis, and less in terms of Plato.

Irigaray’s theories, I came to realize, are deeply informed by her Catholic upbringing. In Irigaray’s work, the sexed body matters. The sexed body speaks. The sexed body is the frame through which one encounters the other and the world. The sexed body is not simply a tabula rasa upon which social meanings have been heaped. Because of this, because she takes the body seriously, she is often charged with that deadly feminist sin: essentialism. For Irigaray, like John Paul II, the body reveals the person, and under her influence in graduate school, I shifted my attention away from imagination to incarnation. Though I did not know it at the time, this was a profoundly Catholic move, because the Catholic imagination is that which takes as its starting point the reality of the Incarnation and the sacramentality that flows from it.

This, however, was as far as Irigaray could take me. Despite Irigary’s Catholic leanings, her work is fundamentally agnostic on the question of whether or not God—as a reality external to the self—exists. She had been a faithful guide thus far, but to step through the River Lethe, I needed someone else to lead the way. The female body speaks for Irigaray, yes, but she only speaks her own language, not the language of God. Eventually, two new guides came to my aid: two Catholic women writers, both converts like myself: Gertud von le Fort and Sigrid Undset.

In her short but profound treatise The Eternal Woman, Gertrud von le Fort provides a framework for understanding the significance of woman in the Catholic imagination, by invoking the concept of divine symbol:

Symbols are signs or images through which ultimate metaphysical realities and modes of being are apprehended, not in an abstract manner but by way of a likeness. Symbols are therefore the language of an invisible reality becoming articulate in the realm of the visible. This concept of the symbol springs from a conviction that in all beings and things there is an intelligent order that, through these very beings and things, reveals itself as a divine order by means of the language of its symbols.

Through the rest of the book, von le Fort describes the three symbolic dimensions of woman: virgin, mother, and bride. This embodied symbolism is not determined by factual circumstances—each woman is simultaneously, regardless of her state or stage in life, a virgin, mother, and bride. “The individual carrier,” writes von le Fort, “has an obligation toward his symbols, which remain above and beyond him . . . The bearer may fall away from his symbol, but the symbol itself remains.”

The Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy by Sigrid Undset dramatizes the symbolic meaning of woman, as well as the capacity for the bearer of the symbol to “fall away” from it. In Undset’s fiction, both of these dimensions are expressed and intertwined: the sacramental proclamations of our bodies and the world, as well as the havoc wrought by our wayward wills.

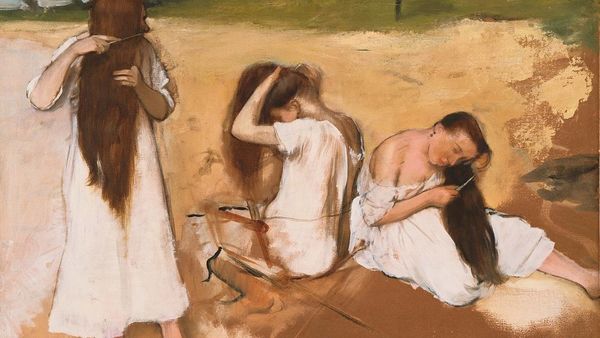

The trilogy calls attention to the symbolic plane by tracing all stages of Kristin’s life—virgin, bride, wife, mother. The physical and emotional intensities of each stage are depicted viscerally; I have never the bodily life of a woman break into language so clearly—the erotic longing of passionate love, the harrowing hyperreality of childbirth, the pain and urgency of engorged, lactating breasts. There are moments when the facticity of her body becomes a mirror of divine things, like when Kristin is on a penitential pilgrimage, and her infant son’s “little mouth at her breast warmed her heart so well, it was like soft wax, easy for heavenly love to shape.”

And it is this heavenly love that is most real, reflected dimly in the earthly loves that preoccupy Kristin’s mind and heart. Undset describes this mirroring between heaven and earth midway through the trilogy, when Kristin’s brother-in-law, Gunnulf, admonishes her: “You cannot settle for anything less than the love that is between God and the soul,” he says, “All other love is merely a reflection of the heavens in the puddles of a muddy road.” He continues, “but if you always remember that it’s a reflection of the light from that other home, then you will rejoice at its beauty and take good care that you do not destroy it by churning up the mire at the bottom.” This love—this fertile, fruit-bearing love—between the creature and her Creator is the essence of woman’s symbolic meaning.

In the last moments of her life, the earthly meanings of Kristin as virgin, bride, and mother have been stripped away—she has bid goodbye to her children, many of whom have now died in the plague, and here on her deathbed, she gives away her wedding ring to ensure Masses will be said for a dead woman, whose abandoned, plagued-ridden body she had rescued and kissed. It is in these final, sacrificial acts—saving an orphan boy from a desperate mob and carrying his dead mother’s body to consecrated ground—that the depth of Kristin’s spiritual motherhood is revealed. In these moments, Kristin actualizes her symbolic meaning, becoming a “maternal woman” in a spiritual sense, as described by von le Fort, who does not “remain the mother of only her own children,” but turns “especially to the helpless, [inclining] lovingly and helpfully to every small and weak thing upon earth.” And Kristin is now truly a bride, giving herself over, in her “last clear thought . . . before death,” to a divine love that is stronger than death:

It seemed to her a mystery that she could not comprehend, but she was certain that God had held her firmly in a pact which had been made for her, without her knowing it, from a love that had been poured over her—and in spite of her willfulness, in spite of her melancholy, earthbound heart, some of that love had stayed inside her, had worked on her like the sun on the earth, had driven forth a crop that neither the fiercest fire of passion nor its stormiest anger could completely destroy.

This is the far more interesting story: not a woman at war with the powers of man, but a woman at war with her own soul.

This is also the central drama of von le Fort’s own novel The Song of the Scaffold, about a group of Carmelite nuns who are executed during the French Revolution. Toward the end of the novel, Sister Marie of the Incarnation begs to be allowed to die with her sisters, but must resign herself to a different kind of martyrdom: being the lone survivor. As she considers the silence of Mary at the cross, she is able to accept that fate, and in that moment her face becomes a mirror of her namesake: “Her resistance broke . . . her face first showed that peculiar expression in which one could suddenly see how she must have looked as a child. It was as if an early, most lovely and delicate painting had become visible under some splendid Baroque restoration.”

Marie wants to be martyred with her sisters, to be the last voice singing the Veni Creator Spiritus on the scaffold, but that honor falls instead to the fragile, fearful Blanche. Blanche is the coward, the failed nun, the runaway. Yet she is the unlikely heroine, the last voice singing to God as the corpses fall. In this moment, the weak and cowardly Blanche is likewise transfigured, her “small pinched face stood out from its surroundings and discarded those surroundings like a wrap or a shawl.”

“I recognized that face in every feature,” says the narrator, a living witness of the executions, “and yet I did not recognize it . . . In that hour, I was like a child who drops through all the layers of being to the very foundation of all things which is a foundation everlasting because it belongs to God.” Layers of being, faces transfigured, a hidden image resurfacing within a painting—Von le Fort, like Undset, writes simultaneously along two planes: temporal and eternal, human and divine, fact and symbol.

The limitation of feminist literary theory and feminist fiction is this: the drama is purely human. The divine, if admitted at all, is merely a projection, an echo in an airtight room. But as von le Fort’s narrator affirms, at the end of her novel: “The purely human is not enough.” It is under the dome of the Catholic cosmos, and within the pages of the writers who live there, that what has long been voiceless is allowed to speak, to say beautiful and unsettling things. Here, the mountain speaks. The body speaks. And not merely its own language, but the language of a loving, self-revealing God.