Introduction

For a certain generation of those who studied theology, namely those who came of age in their theological studies in the 1960s and 1970s, the name of Bernard J. F. Lonergan was constantly referenced. For my generation of theologians, when one mentions Lonergan, it is all too often looked at askance. As I argued elsewhere , for many, Lonergan is neither fish nor fowl. For some, he is not sufficiently radical enough, considered too indebted to Tradition. To others, his thought is considered not sufficiently Thomistic, far too eclectic in his thought. And still, there are others who point to him as the one providing the blueprint for the philosophy behind a relativistic theology of pluralism with his development of the concept of historical consciousness.

I have been asked if my interest in Lonergan is merely a historical curiosity, a desire to look into a period of time in Catholic theology that has since passed. To be honest, the more that I consider that question, I must admit that this is partly true. After I had defended and published my doctorate in theology at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University, which involved a study of John Courtney Murray through the lens of both Bernard Lonergan and Robert Doran, my doctoral director actually asked me if I was really as interested in theology as much as the history of theology. I am fascinated by the way that thought develops, especially in the Western theological tradition.

I have often been asked, repeatedly in some circles, if Lonergan really has anything to offer in an all-too fractured theological world. To this question, I can only answer in the affirmative: yes, Lonergan has something to offer for theology today. In the history of twentieth-century Roman Catholic theology, are there figures who have had and will no doubt have more influence in the “long run” than Bernard J. F. Lonergan? I believe that de Lubac, Congar, Balthasar, Chenu, Ratzinger, Rahner, and Garrigou-Lagrange, just to name a few, have had a greater impact on Roman Catholic theology in toto than Lonergan. I do not believe that this is a debatable issue. Lonergan himself did not help to draft any of the documents of the Second Vatican Council. One can examine the documents of the Second Vatican Council and attempt to ascertain where Lonergan’s influence might have been present (one need look only to the work of John Courtney Murray, especially in the immediate time period leading up to the drafting of Dignitatis Humanae).

Lonergan’s thought, at this time in the history of Catholic theology, is largely limited to Anglophones with only a few non-English speakers demonstrating a real interest in his thought. And yet, some of those whom he has influenced, those who have used his theology, for better or for worse, have influenced thousands of students of theology over the years.

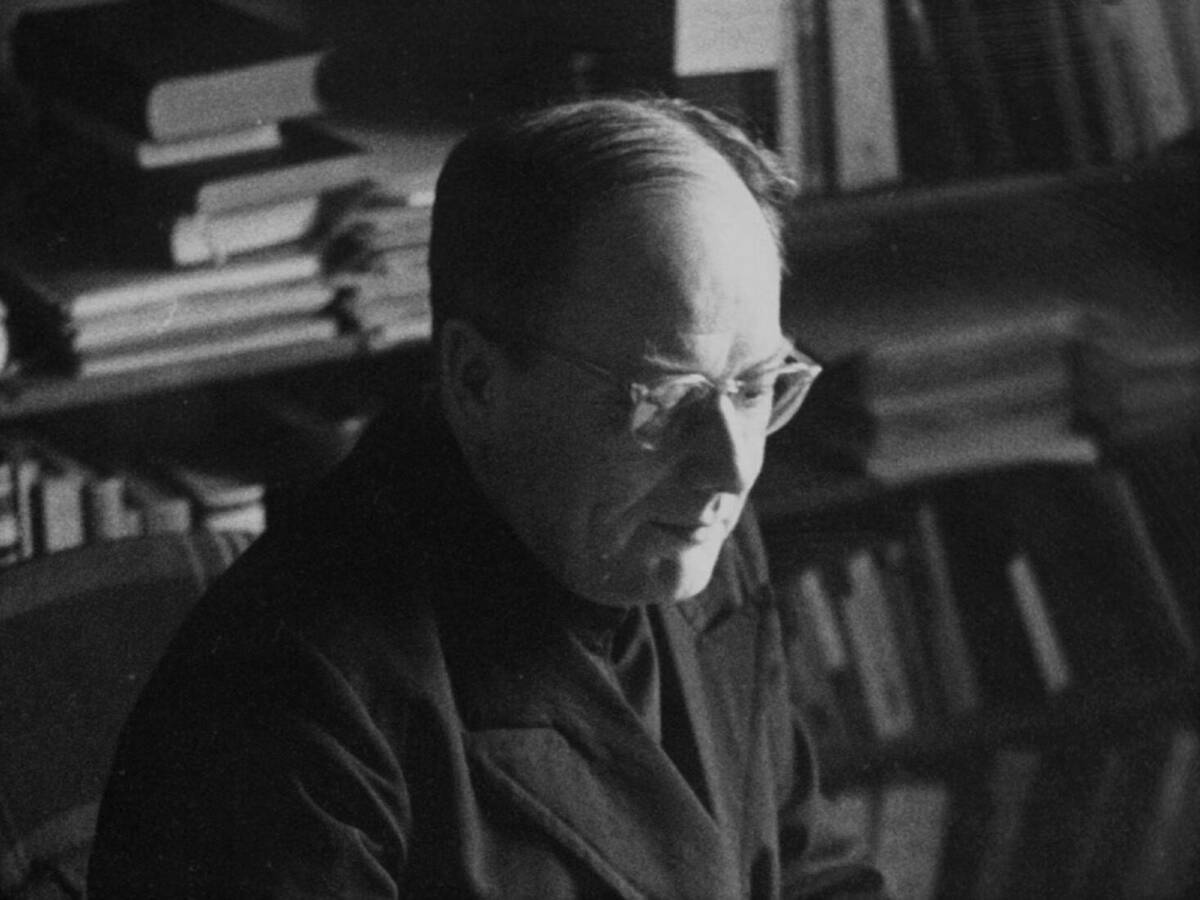

Bernard Lonergan is a key and vital figure in the history of twentieth-century theology. It is my intention in this article to offer readers a brief biographical sketch of Lonergan’s life and intellectual influences which will lead to a second piece, one which will help us understand Lonergan’s basic theological method. For those already familiar with Lonergan, these articles might prove to be too basic. For those who might be unfamiliar with Lonergan’s life and work, it is my hope that these brief pieces might serve as a primer.

Bernard Lonergan—Theologian in Context

Bernard Lonergan was born on December 17, 1904 in Buckingham, Quebec, Canada. Gerald Lonergan, his father, was part of a long-settled family of Irish descent living as Anglophones in a predominantly Francophone area. Gerald Lonergan was, by training and profession, an engineer, eventually becoming a land surveyor. His mother, Josephine Wood, was of English descent, and her family arrived in Canada by way of the United States, with her family emigrating at the time of the American Revolution. By all accounts a devout woman, her family had become Catholic two generations before.[1] From his father, Lonergan had learned not only the importance of possessing a mathematical mind[2], but also the importance of honesty. Bernard Lonergan described his father as “(T)he most honest man I ever met.”[3] From his mother, young Lonergan developed two traits which would prove essential in his life: first, a love of God and second, a love of culture. Josephine Lonergan was a member of the Dominican Third Order and had a great devotion to the rosary.[4] She also possessed a talent for music and particularly enjoyed Beethoven.[5] Born into a stable and loving family consisting of two other brothers,[6] the young Bernard Lonergan developed a love of learning and a sense of wonder.[7]

The Young Lonergan: Philosophy and Social Concern

Lonergan attended a Jesuit secondary school and junior college at Loyola in Montreal. Quickly, he became immersed in what he would describe in his later writings as a “classicist culture” and the experience of living in this culture later offered him the insight that he needed to transcend that particular “cultural matrix.”

When I was sent to boarding school when I was a boy, there were no local high schools- that sort of thing did not exist, you were sent out to a boarding school- the one I went to in Montreal, in 1918, was pretty much along the same lines as Jesuit schools had been since the beginning of the Renaissance, with a few slight modifications. So… I can speak of classical culture as something I was brought up in and gradually learned to move out of.”[8]

Lonergan, later in life, was rather critical of his Jesuit education. He writes: “At Loyola my acquired habits did not survive my first year: by the mid-terms I was in 3rd High; by the end of the year I was fully aware that the Jesuits did not know how to make one work, that working was unnecessary to pass exams, and that working was regarded by all my fellows as quite anti-social.”[9]

Lonergan’s Jesuit Vocation

After an illness, Lonergan discerned a religious vocation and entered into the Society of Jesus in 1921. Reflecting on his formation, the older Lonergan beautifully opines:

Without any experience of just how or why, one is in the state of grace or one recovers it, one leaves all things to follow Christ, one binds oneself by vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, one gets through one’s daily dose of prayer and longs for the priesthood and later lives by it. Quietly, imperceptibly, there goes forward the transformation operated by the Kurios, but the delicacy, the gentleness, the deftness, of his continual operation hides the operation from us.[10]

Receiving the traditional formation that a Jesuit seminarian would receive in those days, Lonergan learned the importance of self-reflection and the need to purify one’s motives through The Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius Loyola. Again, later in life, he would consider the manner in which he was instructed to be a “reduction of St. Ignatius to decadent conceptualist scholasticism.”[11]

Concerning spiritual formation, Richard Liddy comments that, in the time period in which Lonergan was raised, there was a great fear of illusion in the spiritual life and a definite discouragement of speaking about one’s spiritual experiences.[12] Lonergan himself would spend a large part of his later spiritual life rejecting this rigidity, seeking to understand God in a mystical fashion, with love as the entrance way to life in the Divine.[13]

Lonergan’s Philosophical Formation

Lonergan was sent to study philosophy at Heythrop College, England and was also given permission to study for a secular degree at the University of London. Affected very much by the overriding fear of rationalism and modernism, the philosophy taught was by and large a Suarezian neo-Scholastic Thomism, with an emphasis on realism. This realism was based on the notion that a concept is abstracted from one’s sense experience and judgment, in turn, returns the concept to sensible reality. Present was a unity of sense experience and intellect, according to the Aristotelian system. Gerald Whelan notes that even the young Lonergan derided this “abstraction of concept from sense experience” as too simplistic and thought the system to be too “conceptualist.”[14] “Put in a penny, pull the trigger and the transition from box to matches is spontaneous, immediate and necessary.”[15]

Deeply affected intellectually by the Suarezian and neo-scholastic manualism that marked the majority of his philosophical and theological formation, Lonergan began to develop his own theological and philosophical approach, heavily influenced by thinkers like Plato, Augustine, John Henry Newman, and especially Aquinas. Summarizing his intellectual genealogy, Lonergan writes:

I had learned honesty from my teachers of philosophy at Heythrop College. I had had an introduction to modern science from Joseph’s Introduction to Logic and from the mathematics tutor at Heythrop, Fr. Charles O’Hara. I had become something of an existentialist from my study of Newman’s A Grammar of Assent. I had become a Thomist through the influence of Maréchal mediated to me by Stefanos Stefanu and through Bernard Leeming’s lectures on the unicum esse in Christo. In a practical way I had become familiar with historical work both in my doctoral dissertation on gratia operans and in my later study of verbum in Aquinas. Insight was the fruit of all of this. It enabled me to achieve in myself what since has been called Die anthropologische Wende.[16]

Lonergan thus began to create his cognitive theory which could best be termed as “discursive,” because, as Whelan noted, it uses “metaphor of a human conversation or discussion where a number of issues are talked-through before participants agree on a conclusion.”[17]

Lonergan, as mentioned before, used his years of philosophical study to also study secular topics like mathematics that later could be used to teach in Jesuit-run secondary schools. Due to his other intellectual pursuits, Lonergan felt that there was at times direct contradiction between his ecclesiastical studies and his secular studies.

Lonergan’s Philosophical Influences

In his Heythrop years, Lonergan’s discursive cognitive theory developed under his personal study of John Henry Newman, in particular, through his growing appreciation of An Essay in Aid of Grammar of Assent. Newman would state that the ultimate cognitional reference point would be the subject’s experience of the dynamics of one’s own knowing.[18] In addition, the young Lonergan learned from his study of Newman how to use examples from the Church’s tradition as sources for the formation of his own cognitive theory. Another major influence on Lonergan at this point in his life was J. A. Stewart’s platonic philosophy, most especially exemplified in Stewart’s Plato’s Doctrine of Ideas (1909). In a very real sense, the budding theologian learned from Stewart the importance of knowing context and the reality of historical consciousness. From Stewart, Lonergan learned that Plato’s insights in psychology and philosophy were valid, but had to be transposed to address the growth that had occurred over the centuries.

From his study of Newman, which led him to Stewart’s Plato, Lonergan discerned that what is meant by Platonic ideas is actually the sense of wonder in the human subject. Lonergan also found in Plato an important dialogue partner about what was becoming for him a major concern, culture. Liddy writes: “What will become evident in Lonergan’s unpublished writings from the mid-thirties is that Plato gave Lonergan the sense of normativeness of intelligence in its own right, a normativeness that in Plato becomes the means of cultural critique”[19] and further, “The achievement of Platonism lay in its power of criticism. The search for a definition of virtue in the earlier dialogues establishes that virtue is a certain something, the emergence of a new light upon experience. The discovery of the idea, of intelligible forms, gave not only dialectic but also the means of social criticism. For it enabled man to express not by symbol but by concept the divine.”[20] It is this normativeness that Lonergan would bring into his later analysis of culture. Lonergan writes:

“Towns and cities will not be happy till philosophers are kings” is the central position of Plato’s Republic, and the Republic is the centre of the dialogues. To Plato, Pericles, the idol of Athenian aspirations, was an idiot; he built docks and brought the fruits of all lands to Athens…but he neglected the one thing necessary, the true happiness of the citizens. For did not the dialectic reveal that no man without self-contradiction could deny that suffering injustice was better than doing injustice, that pain was compatible with happiness, that shame, the interior contradiction, the lie in the soul of a man to himself, was incompatible with happiness.[21]

Later in life, Lonergan became very interested in Eric Voegelin’s Platonic interpretations, especially as they pertained to culture. Lonergan stated: “I had always been given the impression that Plato’s dialogues were concerned with the pure intellect until I read Dr. Voegelin and learned that they were concerned with social decline, the break-up of the Greek city-states. It was human reasonableness trying to deal with an objective social, political mess.”[22] In this sense, as will be discussed in later chapters, the task of Lonergan, Doran, and Murray is similar to Plato—using “human reasonableness…to deal with an objective social, political mess.”

Lonergan, concerning Plato, writes: “I don’t think that he has the answers but certainly he can build up interest and start some serious questions.” [23]However, he was troubled by the fact that Plato was more concerned with the act of direct insight than the judgment of truth that was necessary to produce the act.[24] He states: “I got interested in Plato during regency and come to understand him; this left my nominalism quite intact but gave a theory of intellect as well.”[25] Naturally enough, this lack in Plato led Lonergan to the work of the neo-Platonist, Augustine of Hippo. From Augustine, Lonergan retrieved a notion on how insight leads the subject to the affirmation of truth, as well as a Christian understanding of the Divine as the object of knowing and that the desire to know the good and true in created reality is an indication of the presence of the Divine within us.[26]

Lonergan’s Theological Formation

For his theological formation, Lonergan was sent to study at the Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome. Ordained to the priesthood in 1937, he completed his doctoral work in 1940 with his thesis, Gratia Operans: Study of the Speculative Development of St. Thomas Aquinas.[27] His “eleven-year apprenticeship to St. Thomas Aquinas,” was fruitful, bearing his work on cognitional theory in Aquinas, which would, in fact, be essential for his later major work in Insight: A Study in Human Understanding.[28]

Lonergan’s Theological Influences

During his studies at the Gregorian University, Lonergan was able to rediscover the importance of Aquinas after stripping the Doctor Comunis of all the Suarezian residue that had accumulated over the years. This rediscovery occurred through three Jesuits Thomists: Peter Hoenen, Joseph Maréchal and Leo W. Keeler.[29] From Hoenen, Lonergan learned to return to what Thomas Aquinas had actually written and not to simply rely on the interpretations of the neo-scholastics, who in a very real sense attributed the thought of the nominalist John Duns Scotus to his polar opposite, Thomas Aquinas.[30]

From Joseph Maréchal, Lonergan, although never an actual classroom student of this Belgian professor, learned the value of interdisciplinary Thomistic research. Maréchal’s familiarity with modern psychology added an extra dimension to the study of Thomism. One of the major contributions of Joseph Maréchal to Thomism was the inclusion of the thought of contemporary philosophers and concepts, like Kant’s “transcendental turn to the subject.” From this point, Lonergan’s cognitive theory, one based on a discursive method, gains more credence by basing itself in the belief that “knowing is more than just taking a good look.”[31]

Finally, Lonergan was influenced in his re-appreciation of Aquinas through his reading of Leo Keeler. From Keeler, Lonergan learned that in the discursive process of human knowing, it was necessary to distinguish between a cognitive level of insight and the level of judgment.[32] In the course of his studies, Lonergan came to what he would later call his intellectual conversion. In the course of writing a letter to his superior in January 1935, Lonergan, after some years of deep emotions and much reflection, confidently declared: “I am certain (and I am not one who becomes certain easily) that I can put together a Thomistic metaphysic of history.”[33] He can do so by working through a level of self-reflection, beginning with “an initial Cartesian cogito.” This turn to the subject would prove to be an essential element in Lonergan’s cognitive theory.[34]

Lonergan’s Growing Social Concern

All the while that Lonergan was growing in his own intellectual conversion, he was also growing in his social concern and awareness. Influenced by papal encyclicals like Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum (1891) and Pius XI’s Quadragessimo Anno (1932) as well as the reality of worldwide events like the great depression, Lonergan was acutely aware of the reality of poverty. He writes: “The political economists are utterly discredited: no economist today believes in the old theories; no thinking man who has lived through the Depression can accept the view that the great happiness of the greatest number results automatically from the laws of supply and demand.”[35] Influenced by his studies in Heythrop under the rare non-Suarezian Lewis Watt, Lonergan learned that economic theory must be part of any wider philosophy of history.[36] The young Jesuit also studied at the University of London where he learned the work of empiricist philosophers like Bertrand Russell and John Stewart Mill and saw in their work a demonstration that mathematics and the natural sciences had a tremendous impact on questions of epistemology and metaphysics, eventually influencing Lonergan’s philosophy of history. From his studies of J.A. Stewart’s Platonic theory, Lonergan grew in understanding of the role of virtue in citizens in the creation of a just society.[37]

One final major influence on Lonergan was the historian Christopher Dawson. In his attempt to ascertain how present-day Western civilization could learn from ancient cultures, Dawson suggested an empiricist method that did not read into the older cultures contemporary values and mores.[38] Lonergan commented that “Christopher Dawson’s The Age of the Gods introduced me to my hitherto normative or classicist notion.”[39]

Lonergan and Economics

Lonergan spent his early years teaching in the French-speaking Jesuit theologate, Marie Immaculée in Montreal, eventually being transferred to the Jesuits’ theologate in Toronto. For the sake of brevity, suffice it to say that his growing philosophy of history and his social concern led him to create a theory of macroeconomics. As William Mathews notes, Lonergan considered his work in microeconomics, “An Essay in Circulation Analysis,”[40] to be the second part of the work he had begun with his philosophy of history. He also mentions that prior to working on the actual essay, Lonergan wrote a four-page schema of his ideas (around 1940-1941) for the essay, signifying why he would wish to undertake this study in economics. The main reason why Lonergan branched out of his theological pursuits to investigate macroeconomic theory was to study how economics progresses and declines and, in the acquiring of this knowledge, to aid societies in avoiding tragedies like the Great Depression in the future. Many of the ideas that Lonergan would develop in Insight are first articulated here. What is needed is a patient adherence to one’s own cognition. Mathews comments:

Economic production is also for Lonergan a series of conditioned emergencies, the emergent component of what he will later call emergent probability; ‘In making a coat of mail each new link has to be added to previous links, and similarly the successive stages of economic progress presuppose the previous and arise from them.’ Each stage having emerged, there is the challenge of survival, and so in time the stagecoach gives way to the train, clipper ships to steamers, money changers give way to brokers who in turn give way to banks and financiers.[41]

The one who is charged with analyzing the economic systems him- or herself has to be intellectually converted so that he or she can be able to respond to the changes that inevitably will occur. The economic analyst needs to be aware that knowledge is more than just “taking a good look.” Having a proper cognitive theory is essential in the creation of a just economy. The flow of services and goods is of primary importance to Lonergan and he sees that this is where governments can assist their citizens concretely. Money flow is involved in this process. Whelan summarizes Lonergan’s thought:

Lonergan identifies two ways in which this involvement occurs: the first involves the way money exercises a kind of direct “oiling of the wheels” of production, consumption, and exchange in an economy. This ordinary use of money includes paying salaries to workers who produce goods that they can themselves buy.[42]

Money is also involved in the creation of new products and technology that can aid in the production of goods. Investment must play an important role in the stability of an economy. According to Lonergan, there are four key phases in an economy:

A capitalist phase that transforms the means of production: a materialist phase that exploits new ideas to raise the standard of living: a cultural phase that turns material well-being and power to equipping the developing cultural pursuits: a static phase in which the process lies fallow and non-economic activity develops independently of material conditions.[43]

In essence, Lonergan was seeking “a stable and permanent solution for the monetary requirements of a long-term expansion.”[44] Lonergan also created a system for governments, who bore the primary responsibility for safe economic system to regulate economy that involves different levels of taxation and interest rates.

Lonergan and Pastoral Theology

It is during this time period that Lonergan decided to publish his Verbum articles for publication in the newly formed Theological Studies, edited by John Courtney Murray. At the same time, Lonergan was also involved in discussion of practical matters like his apostolate at the Thomas More Center in Montreal, which primarily involved adult education classes in theology as well as in his work as an essayist in a local Catholic magazine, The Montreal Beacon. All this is mentioned to exemplify the “polyphonic interests”[45] in which Lonergan was engaged.

Lonergan, Rejection and Redemption

In 1947, Lonergan underwent what has been described by Mathews as his “year of crisis.” This “year of crisis” occurred in no small part due to emotional and physical problems accentuated by his transfer from Montreal to a new English speaking theologate in Toronto.[46] However, the more primary cause of this crisis was the rejection of his 1943 article “Finality, Love, Marriage.” The editor of the magazine in which the article was published wrote that Lonergan’s article directly contradicted the teaching of the Catholic Church concerning marriage. This accusation caused Lonergan great personal pain; nonetheless, he continued to believe that the Church was basing itself on philosophy that could not fully comprehend all the issues at hand. However, as a loyal son of the Church and of Saint Ignatius, he remained silent and did not address these accusations.[47] While he in no way suffered persecution to the extent that his American Jesuit confrere John Courtney Murray did for his views, this criticism and some others caused Lonergan great sorrow.[48]

In 1948, Lonergan underwent a kind of spiritual conversion, commenting years later that “After twenty-four years of aridity in religious life, I moved into that happier state and have enjoyed it for over thirty-one years now.”[49] Whelan comments:

Lonergan also achieved a moment of clarity about how to understand his intellectual vocation. He now recognized that his real passion was to clarify the kind of philosophical questions he had always recognized as being foundational to an effective social concern. He now confirmed some decision he had already been making more informally during the preceding years to sideline a series of interests—in a philosophy of history, a theology of marriage, and in macroeconomics—and to concentrate on the line of enquiry he had begun with the first of his Verbum articles.[50]

Lonergan in Rome

From 1953-1965, Lonergan taught at the Pontifical Gregorian University, Rome, until he returned, due to health concerns to Canada. As a professor of dogmatic theology at the Pontifical Gregorian University, he was exposed to students from all around the world. The universality, the catholicity of the Church became apparent to him. He realized that it was necessary for him, as a professor who wanted to engage with his students and to communicate the doctrine of the Church, as well as his own concepts articulated in Insight, to continue his own study.

In 1953, the world, internationally, was still reeling from the horrors of the Second World War and the rise of atheistic communism. The Church, in the pontificate of Pius XII was processing the importance of Humanae Generis (1950) and the impact that it had on theology in general and theologians in particular.[51] Intellectually, Lonergan’s students at the Gregorian were engaging philosophically with phenomenology and existentialism as well as having a growing interest in hermeneutics.[52] Describing this time period, Lonergan writes: “ For the first ten years I was there I lectured in alternative years on the Incarnate Word and on the Trinity to both second and third year theologians. They were about six hundred and fifty strong and between them, not individually but distributively, they seemed to read everything. It was quite a challenge.”[53] Professionally, as an academic, he was on the threshold of publishing what is considered by most to be his greatest work, Insight: A Study in Human Understanding.[54] Lonergan, in this time period (1953-1965), offered a seminar for graduate students at the Gregorian in theological method.[55] Throughout this entire time period, Lonergan himself was increasingly converted, intellectually, morally, and spiritually.

Lonergan: Towards the Functional Specialties

In February 1965, Lonergan began to come to the insight of functional specialties. In June 1965, while visiting Canada and undergoing a routine medical examination, Lonergan was diagnosed with lung cancer, and, for reasons both physical and emotional, it was determined by his superiors that he would leave his teaching position at the Gregorian University and remain in Canada, as a research professor at Regis College, Toronto.

His illness left him much in a weaker state, and Lonergan’s work on the functional specialties took him much longer than he originally anticipated. The article on functional specialties was finally published in 1969 in Gregorianum and was adapted to become the fifth chapter, “Functional Specialization,”[56] in his Method in Theology, a work Lonergan produced while a research professor at Boston College as a culmination of his desire to create a theological method for Christian theology.

Conclusion

In November 1984, Lonergan died in his native Canada. Frederick Crowe, in the homily given at the funeral Mass of Bernard Lonergan, said:

Writing of the good choices and actions that make us what we are, he (Lonergan) calls them “the work of the free and responsible agent producing the first and only edition of himself” . . . that is a book I and each one of us must write alone as we go through life, producing day by day a new paragraph to achieve the first and only edition of myself… The one and only work that really mattered was the work of which he wrote last Monday morning the final paragraph, and turned it over to his maker for censorship and—we have not the slightest doubt—for divine approval.[57]

Few outside theological circles might recognize the impact that Lonergan accomplished in his lifetime, most especially through his works, Insight and Method in Theology, but in his own self-actualization, Lonergan offers all who strive to practice the science and art of theology the challenge of the Delphic oracle: “Know Thyself.” Only through a four-fold conversion, intellectual, moral, spiritual, and psychic can one truly offer to the Church and the culture a theology that is authentic and true.

[1] Valentine Rice, “The Lonergans of Buckingham,” Compass (Journal of the Upper Canada Province of the Society of Jesus, March 1985): 4-5.

[2] The young Lonergan states: “In elementary school I liked math because you know what you had to do and could get an answer…” in Caring About Meaning: Patterns in the Life of Bernard Lonergan, (Montreal: Thomas More Institute, 1982), 2 and further “I remember in algebra doing a problem and getting a minus answer. I was sure that I was wrong and I asked, but was told, ‘Oh no, that’s right. It was the revelation of negative numbers.” Caring About Meaning, 133.

[3] Caring About Meaning, 40.

[4] Ibid. Bernard Lonergan comments: “She joined the Third Order of Saint Dominic and said the beads three times a day for the rest of her life, as far as I know. The Scholastics teaching me at Loyola would come and visit me at the hospital, and they thought she was a very holy woman.”

[5] William Mathews, “Lonergan’s Apprenticeship,” Lonergan Workshop 9, edited by Fred Lawrence (Boston College, 1993).

[6] Gregory Lonergan followed in his older brother’s path and became a Jesuit. The youngest brother, Mark, was an engineer. See Richard M. Liddy, Transforming Light: Intellectual Conversion in the Early Lonergan (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1993), 4.

[7] The older Lonergan recounts an early episode of wonder in his life: “When I was a boy, I remember being surprised by a companion who assured me that air was real. Astounded, I said, ‘No, it’s just nothing.’ He assured me that ‘There’s something there, all right. Shake your hand and you will feel it.’ So I shook my hand, felt something, and concluded to my amazement that air was real.” See Lonergan, “The Natural Theology of Insight,” (an unpublished paper given at the University of Chicago Divinity School, March 1967), 3, as recounted in Liddy, 4.

[8] Lonergan, Second Collection, 13.

[9] Lonergan, Letter of May 5, 1946, to John L. Swain; quoted in Frederick L. Crowe, Lonergan (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1992), 5 as well as in Liddy, 6.

[10] Lonergan, Collection, 230-231.

[11] Lonergan, Caring About Meaning, 145. He would also add “… ‘examine your motives.’ When you learn about divine grace you stop worrying about your motives; someone else is running the ship.” (Caring about Meaning, 145)

[12] Liddy, 7.

[13] Lonergan, Method in Theology, 290. Liddy comments that there was a breakthrough in Lonergan’s prayer life around 1946 (Liddy, 7).

[14] Whelan, 16.

[15] Lonergan, “The Syllogism,” Blandyke Papers, quoted in Liddy, 22.

[16] Bernard Lonergan, A Second Collection: Papers by Bernard J. F. Lonergan, S.J., edited by W. F. J. Ryan and B. J. Tyrell (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1974), 263.

[17] Whelan, 16.

[18] Whelan, 17. Whelan comments: “Newman alerted him to the fact that there is something prior to an act of judging truth that involves a mysterious relatedness to God whose light shines through our ‘moral as well as our intellectual being’

[19] Liddy, 48.

[20] Unpublished notes on philosophy of history, available at the Lonergan Research Institute, Toronto, quoted in Liddy, 48.

[21] ibid, as quoted in Liddy, 48.

[22] Lonergan, quoted in The Question as Commitment: A Symposium, edited by E. Cahn and C. Going (Montreal: The Thomas More Institute, 1977), 119.

[23] Lonergan, Caring About Meaning, 49. Liddy (47) notes that in the mid-1930s the Platonic dialogues were among the few books that Lonergan actually owned. Lonergan, in time, gave up his study of Plato, and stated: “I had other fish to fry.” (Caring About Meaning, 48).

[24] Whelan, 18. See also Liddy, 49.

[25] Lonergan, Letter to Provincial, Henry Keane, January 22, 1935, quoted in Liddy, 49.

[26] Whelan, 19.

[27] The dissertation was later published as Grace and Freedom: Operative Grace in the Thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan 1, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000).

[28] Lonergan’s work in cognitive theory would be published as a series of five articles in Theological Studies in the years 1946-1949. These articles would later be published in collected form as Verbum: Word and Idea in Aquinas, Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan 2, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997).

[29] See Whelan, 20-26.

[30] See Whelan, 21 and Liddy, 94. Lonergan writes: “Scotus posits concepts first, then the apprehension of nexus between concepts…while for Aquinas understanding precedes conceptualization which is rational, for Scotus, understanding is preceded by conceptualization which is a matter of metaphysical mechanics. (Liddy, quoting Lonergan, Verbum, 25n-26.)

[31] Whelan (23, footnote 18) summarizes the thought of Michael Vertin on the connection of Joseph Maréchal and Bernard Lonergan. He quotes Vertin: “Lonergan unreservedly endorses Maréchal’s contention that I have my notion of being in general, my idea of all reality, by nature rather than by acquisition…it only prefigures being in its determinate plenitude” and “Lonergan also vigorously embraces the most prominent element in Maréchal’s account of how I know particular beings. The culminating step of the process is never a matter of confrontation, perception, taking a good look—on the contrary, [it] always culminates with judging, where judging is posited, asserting, affirming. Michael Vertin, “The Finality of Human Spirit: From Maréchal to Lonergan,” Lonergan Workshop Volume 19, “Celebrating the 450th Jesuit Jubilee,” edited by Fred Lawrence [Boston: Boston College, 2006]: 275.

[32] Whelan, 23-24; Liddy, 96-100.

[33] Lonergan, “Letter to Fr. Keane,” January 22, 1935, quoted in Liddy, 108.

[34] Lonergan, “Letter to Fr. Keane,” January 22, 1935; quoted in Liddy, 109-110; Whelan, 26. Lonergan writes: “The current interpretation of St. Thomas is a consistent misinterpretation- From an initial Cartesian “cogito” I can work out a luminous and unmistakable meaning to intellectus agens et posibilis, abstraction, conversion to phantasm, etc., etc. The [neo-Scholastic] Thomists cannot even give a meaning to most of this… I can put together a Thomistic metaphysic of history that will throw Hegel and Marx, despite the enormity of their influence on this account, into the shade.”

[35] Lonergan, as quoted in William Mathew, Lonergan’s Quest: A Study of Desire in the Authoring of Insight (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), 111.

[36] Watt also introduced his students to the thought of Karl Marx as well as the papal social encyclicals, thus solidifying in the young Lonergan’s mind the need to know and appreciate contemporary philosophy. See Matthew, 33, 41-43 and Whelan, 28.

[37] Liddy, 48; Whelan, 29.

[38] See Christopher Dawson, The Age of the Gods (1928).

[39] Lonergan, “Insight Revisited,” in A Second Collection, 264.

[40] Lonergan, Macroeconomic Dynamics: an Essay in circulation Analysis, Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan 15 (Toronto: University of Toronto, 2005).

[41] Mathew, 115, as quoted in Whelan, 41.

[42] Whelan, 42.

[43] Lonergan, as quoted in Mathews, 15.

[44] Mathews, 121.

[45] This metaphor, “polyphonic interests” is used by Mathews to refer to the years 1940-1947. Gerard Whelan extends the time period to include Lonergan’s years of doctoral studies (1938-1940).

[46] See Mathews, “A creative illness,” 185-90 and Whelan, “Emotional Problems,” 52.

[47] See Mathews, 128; Whelan, 53.

[48] Mathews (182-184) details a critique of his Verbum articles in Modern Schoolman by Jesuit scholastic Matthew J. O’Connell as well as a rejection on the part of some economists of his “An Essay in Circulation Analysis.” (130)

[49] Mathews, 189.

[50] Whelan, 55.

[51] It should be noted that this is the same time period that John Courtney Murray in the United States was working out his theories of Church and State relations. The Holy Office, under Alfredo Cardinal Ottaviani, was in a contentious relationship with several theologians, among them Karl Rahner, Henri de Lubac and John Courtney Murray.

[52] As a professor of dogmatic theology during the academic year, Lonergan was pleased to offer in the summer months several “Summer Institutes” throughout the United States and Canada.

[53] Lonergan, A Second Collection, 276.

[54] It is beyond the scope of this dissertation to discuss the monumental impact that Insight (CWL 3, 1991) had on cognitive theory and Lonergan’s later works, like Method in Theology. Insight also had a tremendous impact on Lonergan himself. He later writes: “To say it all with the greatest brevity: one has not only to read Insight but also to discover oneself in oneself.” (Method in Theology, 260).

[55] Gerard Whelan notes that these graduate seminars were not offered in the faculty of theology, but in the philosophy faculty “…where, it seems, more creative thought was possible than within the theology department.” (Redeeming History, 129) By and large, Lonergan’s lectures at the Gregorian University were limited to teaching first-cycle students in dogmatic theology, where the curriculum was already predetermined.

[56] See Lonergan, “Functional Specialties in Theology,” Gregorianum 50 (1969):485-504.

[57] Frederick E. Crowe, “Homily at the Funeral of Bernard Lonergan,” in Appropriating the Lonergan Idea, edited by Michael Vertin, (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1989), 389.