A famous reading in the Advent Liturgy of the Hours from Isaac of Stella, Cistercian abbot and contemporary of Bernard of Clairvaux, makes the claim that, among other things, the Christian believer can, like Mary, be a mother of Christ. Beyond the breviary, this has actually become a kind of spiritual commonplace. Every believer can conceive Christ through his or her faith, in a way analogous to Mary.

Speaking for myself, I have never known what to make of this comparison. It seems to rest on the double meaning of the word “conceive:” one can conceive in one’s mind, and one can conceive in the womb. But, methinks, these are really, really different realities despite the double entendre. For that reason, perhaps, the comparison has always seemed inert to me, leaving me utterly unmoved.

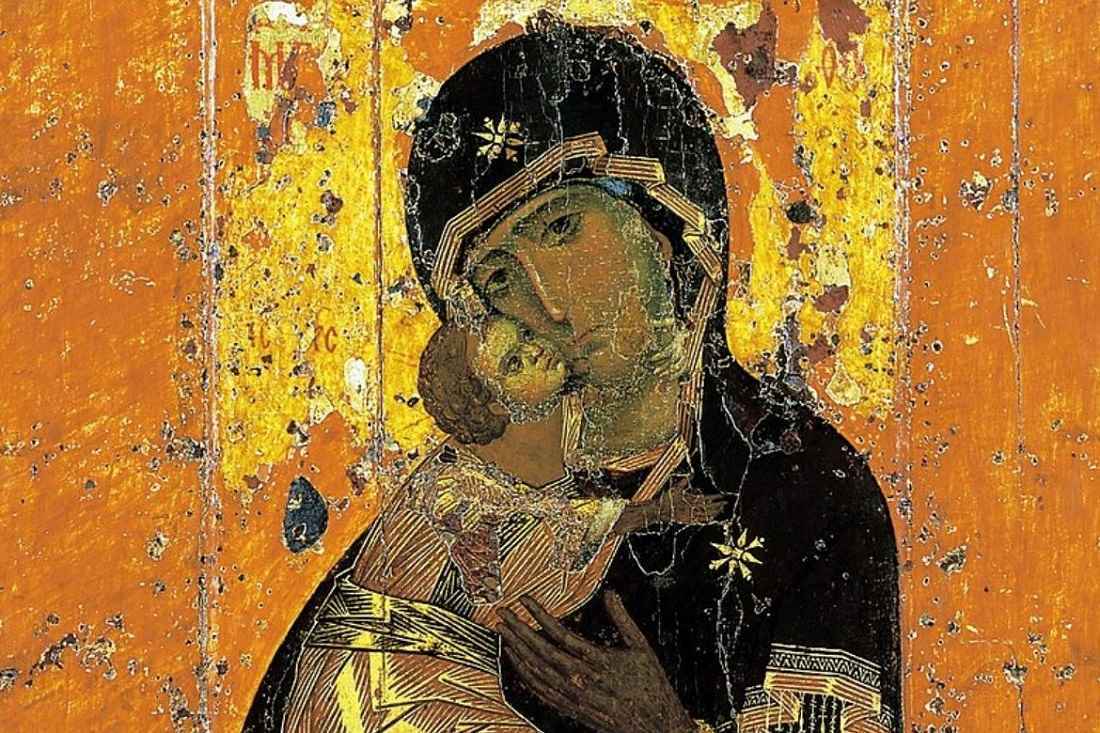

What actually does move me is the wondrous virginal conception of the Word of God in the womb of Mary, the great Mother of God, something so much more stupendous and altogether more marvelous than the metaphorical version of my conception of the Word of God in my thought or even in my faith. I can’t imagine the equivalent of the icon of, say, Our Lady of Vladimir, being painted, but of my metaphorical motherhood of the baby Jesus in my faith—Our Lady of John C. Cavadini, tenderly kissing a thought of his (sic). And, maybe I’m sentimental, but I think the viewer would, at very least, miss the cute little bare feet of the very dignified, but unmistakably infant, Christ child, so prominent in this type of icon. Those little feet alone, the bare baby feet of the divine Wisdom by which the whole world was created marked as such by the regal gold “assist” in his clothes, are enough to move even the hardest heart looking at the picture.

Nevertheless, even as I have always felt unmoved by my putative status as a surrogate Mother of God, I’ve always felt guilty about feeling this way. After all, the idea goes back to the Fathers, and not least of all to St. Augustine. Nor is there anything surer than that St. Augustine, the great theorist of the primal sin of superbia or pride, would not approve even of the thought of any idea leading anyone to imagine an icon of Our Lady of John C. Cavadini or of Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, for that matter, or anyone else. So there must be something more to the idea of the individual Christian as metaphorically the mother of Christ, something to which my impatience with the idea has blinded me. But how can we look deeper? Well, we can listen to Bishop Augustine as he preaches on Christmas Day. Conveniently, many of his Christmas sermons are preserved. Let’s eavesdrop on his fourth century Christmas Mass celebrations to find out what more there might be in this idea as he expresses it.

The first thing to notice is that Augustine always fixes our attention on the uniqueness of the birth we are celebrating along with the joy it brings:

Let us rejoice, brothers and sisters; let the nations be glad and exult. It is not this visible sun, but its invisible Creator, who has consecrated this day, when the virgin mother gave birth . . . to the one who became visible for us, by whom, in His invisibility, she herself was created! (Sermon 186.1)

Again, “It is called the Lord’s birthday when the Wisdom of God presented itself to us as an infant” (S. 185.1), and this event is a cause for rejoicing not, in the first instance, because of the miraculous conception of the Virgin, though as we will see for Augustine makes this is a constitutive element in the wonder of Christmas, but because of the unthinkable and unutterably magnificent spectacle of the humility of God the Creator. Augustine employs some of his most stunning oratory to try to utter the unutterable, to imagine the unimaginable:

The one who holds the world in being was lying in a manger; he was simultaneously speechless infant and Word. The heavens cannot contain him; a woman carried him in her bosom. She was ruling our ruler, carrying the one in whom we exist, suckling our bread. O manifest infirmity and wondrous humility in which was thus concealed total divinity! Omnipotence was ruling the mother on whom infancy was depending, was nourishing on truth the mother whose breasts it was sucking! (S. 184.3)

In another sermon, Augustine asks the obvious question, “For whose benefit did such sublimity come in such humility?” and he answers his own question: not for His own benefit but “totally for ours.” This birth is wholly a gift of love, wholly unmerited. For who could merit the self-emptying of the Son of God into the form of a servant (see S. 187.1 & 4, and S. 194.3, citing Phil. 2.6-7)?

The one who was God has become man. The inn was crowded and cramped, so he was wrapped in rags, laid in a manger; you heard it when the gospel was read. Who wouldn’t be astonished? The one who filled the universe could find no room in a lodging-house; laid in a feeding trough, he became our food (S. 189.4).

The love we are celebrating is our food, this love revealed and accomplished in the Incarnation. Augustine is a careful reader of the Bible, and observes that the text of Luke is inviting us to see the Incarnate Love of God, placed in a feeding trough, as Himself food, a Eucharistic image even if appropriately muted at this point in the text. Contemplating the Christmas manger scene, we are contemplating the ultimate comestible, the food of truth, the food which is the love of God and as such satisfies all the deepest hungers of the human creature, hungers that we don’t even realize we have—that we don’t dare realize we even have, until that which satisfies them is revealed to us.

This food, as Augustine is always reminding us, including in his Christmas sermons, is not the “solid food” of the unclothed divine essence shown forth, which would only blind us, but rather the “milk” of the Incarnation, suitable for the weak and vulnerable such as we all are. But what is most noteworthy here is that God’s milk is not in any proper sense His own, but is literally Mary’s actual breastmilk, sine qua non for the Incarnation and constitutive of its humility: “He loved us so much that he became man though he had made man; that he was created from a mother whom he had created, carried in arms he had fashioned, sucked breasts which he himself filled . . . ” (S. 188.2). These are not breasts in general, all filled by the bounty of God as Creator, but Mary’s, the very ones suckled by the Word made flesh. In a sense, Mary’s milk is the literal form God’s milk takes; Mary’s milk, properly hers, is our food because the baby lying in the feeding trough is sustained by Mary’s milk.

Since Mary is a Virgin, her milk, though ordinary milk, is still a special work of the Almighty Creator, part of His willing to be as utterly dependent for nourishment as any other newborn. Mary’s milk is an image not of God’s “motherhood,” but precisely of God’s Fatherhood, and specifically of His Fatherhood of Christ in His divine nature:

To sum up, Christ was born both of a Father and of a mother; both without a father and without a mother; of a Father as God, of a mother as man; without a mother as God, without a father as man (S. 184.3).

Mary’s virginal milk is the direct fruit of the love of God who willed not that He Himself would be the mother of Jesus, but that he would have a real, literal, flesh and blood mother. The humility of the Incarnation is precisely that the Word of God deigned to have a literal human mother, and that the Word who so deigned was truly God, that is, truly and eternally begotten of the Father. That there is no human father, or indeed any father of Jesus in His humanity, is a revelation of God the Father’s love of us. Mary conceived in an act which was totally transparent to this love, an act in which there could have been nothing but freedom, without even the slightest hint that any ulterior motive, of passion or of fear, was involved, but only the Father’s love, the only love by which Mary conceived Jesus, the Word.

In that love, Mary also conceived all of us who are bound—by the very same love—into members of her Son’s body. Her virginity means that all of us bound to Christ as Head and to each other as His members are conceived, as such, in no love but the very same love of the Father. And thus the Church, in her turn, is a virgin, because she is constituted by the very same virginal love in which Mary conceived Jesus.

And this gives rise to a gorgeous paradox of gratitude and purity. Augustine is not hesitant to relish such a paradox with his flock:

And so the virgin holy Church celebrates today the child-bearing of the virgin. It is to the Church, you see, that the apostle says, I have attached you to one husband, to present you as a chaste virgin to Christ (2 Cor. 11.12). How could it be a chaste virgin in so many communities of either sex, among so many, not only boys and girls, but also married fathers and mothers? (S. 188.4)

Augustine really could not be more blunt. How can the Church be a virgin when so many of her members are married and have sex? Because the virginity of the Church is not a function of our either having sex or refraining from sex. The virginity of the Church does not come from us, but it comes from the virginal love, the love with no ulterior motive by which “such sublimity came in such humility,” “totally for our sake,” with no hint of unfreedom or mixed motive, the love of the Father by which the Virgin Mary conceived, the love by which the one in the form of God emptied Himself and became a servant. That love makes the Church a Virgin. And all members of the Church participate in the virginal love which makes the Church and which makes the Church fruitful in baptism.

Notice that the uniqueness of Mary is not dissolved into the Church, for the virginity of the latter, what Augustine calls a virginity of the heart, is dependent on the literal virginity of the birth of Jesus from Mary: “Christ, intending to establish the Church’s virginity in the heart, first preserved Mary’s in the body” (S. 188.4). There is no fetish here about bodily virginity as an absolute value in and of itself, nor, on the other hand, is Mary’s bodily virginity merely a physical sign of a truer, spiritual virginity of the heart. Mary’s bodily virginity is the sign and the realization of the love of the Father of the eternal Word in which the Word was conceived as her son to whom she and Joseph gave the name “Jesus.” Mary’s bodily virginity is the sign and effect of the self-emptying and self-donating love of God, the utterly concrete motherhood of the Word so made flesh that He suckled at her breasts and drank her milk in order to survive. “The Church . . . could not be a virgin unless she had found that the husband she had been given to was the son of a virgin” (ibid.).

So where does this leave us with regard to our own “motherhood” of Christ? It certainly leaves us in a place different from where we started. We have virginity of heart not as a work of ours, but as something (mercy) we are given, which makes us members of the Church. “And so let his mercy come to be in our hearts. His mother bore him in her womb; let us bear him in our hearts.” The same mercy that made the virgin conceive, forms our hearts. Bearing that mercy, we bear Christ, who is mercy. “The virgin was big with the Incarnation of Christ; let our bosoms grow big with the faith of Christ.” In faith we bear the mercy given to us and we grow to the point where we give birth to praise and gratitude for what we have been given, what has made us members of the Church: the virgin “gave birth to the Savior; let us give birth to praise.” This praise is conceived not as a dim competition with the conception and birth of the Savior, but as a response to it, a witness to it, and in that way, a new “birth” of Christ in gratitude for His gifts. “We mustn’t be barren; our souls must be fruitful with God” (all passages from S. 189.3).

So this Christmas let us follow the advice of St. Augustine. Hearing the Gospel of the Incarnation proclaimed, let it be the occasion for our fruitfulness in the virginal love of the Father in which the Virgin conceived as mother, and in which we, realizing we bear Christ in our very person as baptized Christians, may give birth to him in these two simple words: “Thank You!”