Pope Francis frequently speaks of our irresponsible use of goods, the violence in our hearts, unchecked human activity, and how our current models of growth, of production and consumption are unsustainable. He tells us early in Laudato Si' that the deterioration of nature goes hand in hand with deterioration of the culture, and that both share a cause: “Both are ultimately due to the same evil: the notion that there are no indisputable truths to guide our lives, and hence human freedom is limitless” (§6). He echoes St. John Paul II, who writes in Centesimus Annus: “Indeed, what is the origin of all the evils to which Rerum Novarum wished to respond, if not a kind of freedom which, in the area of economic and social activity, cuts itself off from the truth about man?” (§4). Similarly, Pope Benedict XVI’s 2008 social encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, is structured around the belief that love must be firmly based on the truth about the human person (§1-10).

Each Pontiff is concerned with a misunderstanding of what it means to use human freedom.

The Problem of Freedom and Culture

The result of the misuse of our freedom is that we abuse creation. Francis has in mind a set of ecological sins affecting both environment and humanity: the destruction of the biological diversity of God’s creation, the degradation of the integrity of the earth through climate change, the destruction of natural forests and wetlands, and the contamination of the earth’s waters, its land, its air, and its life (Laudato Si', §8). He outlines these in some detail and points in particular to the serious problem of the quality of water that is available to the poor; the results are dysentery and cholera and much suffering as well as a high infant mortality (§29). He discusses a number of ecological difficulties and even disasters faced particularly by the poor of the world to make his point that the world is facing a worldwide ecological crisis.

Pope Francis turns to St. Francis for his radical refusal to turn reality into an object to be used and controlled (§11). We humans have plans for everything but what is lost is a search for God’s plans for creation and ways to put those plans to work (§76). Rather, our response to environmental issues is all too often denial, indifference, resignation or a blind confidence in technological solutions (§14). Indeed, he shares with Benedict XVI a deep suspicion of what he terms the “technocratic paradigm,” which he believes may overwhelm our politics and even impede freedom and justice (§53). The term "technocratic paradigm" refers to culture’s powerful inclination to accept any advance in technology, regardless of its possible impact on humanity and the environment. That tendency is linked to the unthinking acceptance by many who believe that “current economics and technology will solve all environmental problems, and argue, in popular and non-technical terms, that the problems of global hunger and poverty will be resolved simply by market growth” (§109).

Pope Francis urges us to look to nature and our purpose. We share a status as creatures with the entire created order. Everything we are and have emerges from the creating and loving Word of God (§77). Created in God’s image, we reflect that free gift of self and are called to make the same gift. All too often we act as though we are the creators who can define our own nature and the nature of all our environs. God's plan is for us to establish loving relationships in acceptance of God’s plan for the world; when we turn away from that plan, we mistreat each other and the natural environment alike.

Our hearts reflect this resulting inner chaos. Francis tells us that at the base of the huge, excessive, disordered, exacerbated, compulsive, impulsive consumerism that drives the ecological crisis is the dissatisfied and frustrated human heart. He writes, “The emptier a person’s heart is, the more he or she needs things to buy, own and consume. It becomes almost impossible to accept the limits imposed by reality. In this horizon, a genuine sense of the common good also disappears” (§204). The resulting lifestyle and the models of production and distribution built on it are inherently unsustainable. It goes without saying that the business owner, both in supplying wants and in creating them, falls prey to the same cultural reality, via the technocratic paradigm and the general sense of consumerism. Francis juxtaposes this mindset and resultant lifestyle to a lifestyle which can be universalized, a lifestyle of moderation in consumption which is compatible with a sustainable use of the environment. (§50)

Pope Francis does not believe that the pace and volume of our current consumption is sustainable, but he believes that we lack the culture to confront the crisis. Even with those who possess a certain ecological sensibility, Pope Francis notes “it has not succeeded in changing their harmful habits of consumption which, rather than decreasing, appear to be growing all the more” (§55). This paradox is because such efforts to exhibit generosity to the environment are linked to our inability to think seriously about future generations, to broaden the scope of our present interests, and to consider those who are excluded from development (§162). He continues, “Since the market tends to promote extreme consumerism in an effort to sell its products, people can easily get caught up in a whirlwind of needless buying and spending. Compulsive consumerism is one example of how the techno-economic paradigm affects individuals” (§203).

Another example he cites is that the path of current development is one of “excessive technological investment in consumption and insufficient investment in resolving urgent problems facing the human family” (§192). The vulnerable are excluded or marginalized in the process because, “the current model, with its emphasis on success and self-reliance, does not appear to favor an investment in efforts to help the slow, the weak or the less talented to find opportunities in life” (§196). He sums up in a strong statement, “The alliance between the economy and technology ends up sidelining anything unrelated to its immediate interests” (§54).

Pope Francis takes as his own Pope Benedict XVI’s statement which proposed “’eliminating the structural causes of the dysfunctions of the world economy and correcting models of growth which have proved incapable of ensuring respect for the environment’” (§6). Francis critiques the current models of production and consumption, especially the emission of carbon dioxide and other highly polluting gases, urging the replacement of fossil fuels and coming up with sources of renewable energy. He praises the good practices of energy use that exist, but states that they are far from widespread (§26). His preferred alternative is not yet in widespread use:

We have not yet managed to adopt a circular model of production capable of preserving resources for present and future generations, while limiting as much as possible the use of non-renewable resources, moderating their consumption, maximizing their efficient use, reusing and recycling them. A serious consideration of this issue would be one way of counteracting the throwaway culture which affects the entire planet, but it must be said that only limited progress has been made in this regard (§22).

The dominant technocratic paradigm is characterized by five powerful modern myths, all grounded in a utilitarian mindset. They are the myths of individualism, unlimited progress, competition, consumerism, and the unregulated market. Throughout the document, he points out that these myths are either not helpful in building a culture of care (his goal), or are actively harmful in preventing the needed culture from developing. Pope Francis returns to his belief that our goals are not based on the truth of creation in the following statement:

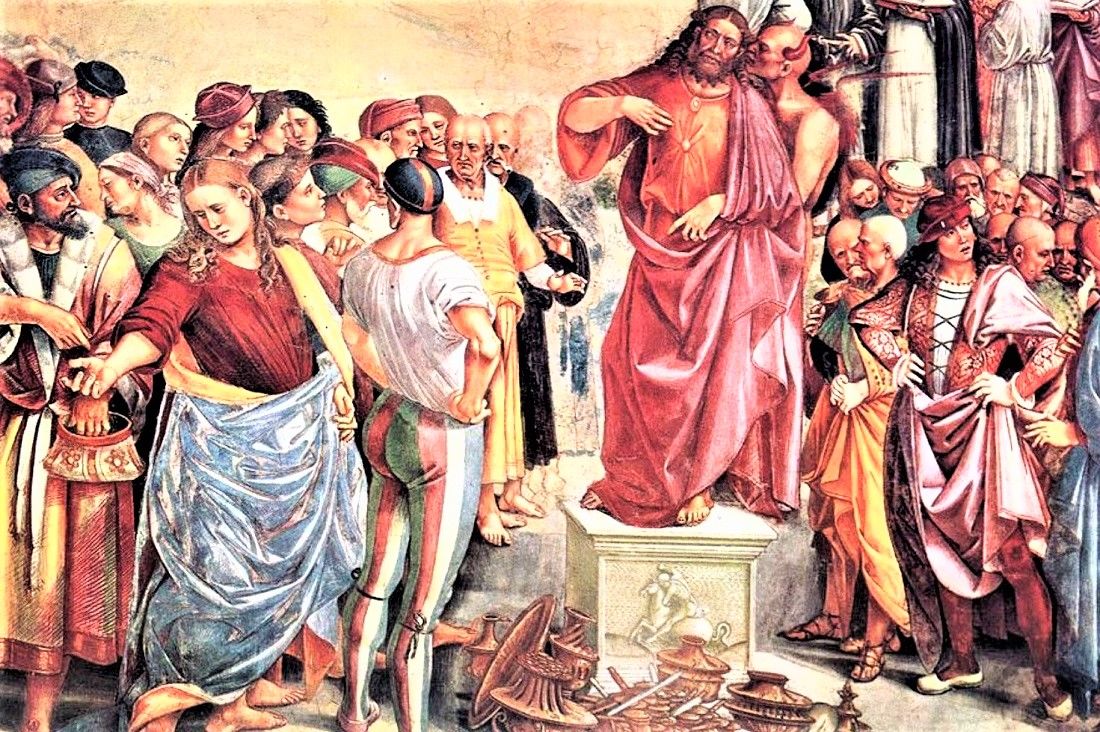

The culture of relativism is the same disorder which drives one person to take advantage of another, to treat others as mere objects, imposing forced labor on them or enslaving them to pay their debts. The same kind of thinking leads to the sexual exploitation of children and abandonment of the elderly who no longer serve our interests. It is also the mindset of those who say: Let us allow the invisible forces of the market to regulate the economy, and consider their impact on society and nature as collateral damage. In the absence of objective truths or sound principles other than the satisfaction of our own desires and immediate needs, what limits can be placed on human trafficking, organized crime, the drug trade, commerce in blood diamonds and the fur of endangered species?

Viewed with an economist’s eye, what these myths all have in common is that they are exacerbated or directly driven primarily by the profit motive since it is markets which provide the means for the instantiation of the technocratic paradigm as exploitation or marginalization of persons or the environment.

He calls for a change in mindset in which we reject a magical conception of the market because environmental problems cannot simply be resolved by higher profits through market solutions. The market will not by itself consider “rhythms of nature, its phases of decay and regeneration, or the complexity of ecosystems” (§190). Moreover, he tells us, “biodiversity is considered at most a deposit of economic resources available for exploitation, with no serious thought for the real value of things, their significance for persons and cultures, or the concerns and needs of the poor” (§190). Their underlying significance and real value is that microorganisms and their bio-systems were created as an act of love by our Creator and “’by their mere existence, they bless him and give him glory’” (§69).

He calls us to turn from the old politics, concerned with facilitating short-term growth and slow to respond to environmental issues, to a healthy politics, capable of reforming and coordinating institutions and committed to the common good in the terms of the above (§178). We need a transparent politics, independent enough of powerful interests, which can require environmental impact assessment from the start of every public spending project, rather than have it be an add-on as a response to civic pressure. In his words:

To take up these responsibilities and the costs they entail, politicians will inevitably clash with the mindset of short-term gain and results which dominates present-day economics and politics. But if they are courageous, they will attest to their God-given dignity and leave behind a testimony of selfless responsibility. A healthy politics is sorely needed, capable of reforming and coordinating institutions, promoting best practices and overcoming undue pressure and bureaucratic inertia (§181).

The new cultural ethos that the Pope suggests requires a renewal of politics. The Pope turns to the Catholic view of society as composed of the state, which he urges to be applied towards the ecological virtues through daily actions to relieve pressure on the environment (§211) and the myriads of intermediate groups, associations, and communities. Such groups are the main way by which we can collectively pursue both the good of the members of the groups and the social and environmental common good. Politics has been unable to deal effectively with environmental issues, and Pope Francis credits the non-government organizations and intermediate communities of the environmental movement with bringing environmental issues to the forefront of society’s concerns (§179). He praises their role in pressuring government to develop more rigorous regulations, procedures and controls and urges citizens and consumers to exert pressure on businesses and corporations to adopt more effective ecological approaches as well.

The Spiritual Renewal of Culture

The ecological crisis is a sign of the ethical, cultural, and spiritual crisis of modernity (§119). We must, in his words, generate “resistance to the assault of the technocratic paradigm” through a “distinctive way of looking at things, a way of thinking, policies, an educational program, a lifestyle and a spirituality” (§111). This resistance is on behalf of all creatures, for Jesus regarded all creatures as important in God’s eyes (§96-97). Pope Francis tells us, “the creatures of this world no longer appear to us under merely natural guise because the Risen One is mysteriously holding them to himself and directing them towards fullness as their end” (§100). Thus, in the hands of Pope Francis, the principle of the universal destination of goods, as first principle of the ethical and social order (§93), teaches the expanded lesson that God created the world for all creatures not just for humans. Therefore, all creatures are to benefit from the use of God’s creation.

Pope Francis is in quest of a way to begin to change today’s throwaway culture into an authentic, responsible culture, with “a sound ethics, a culture and spirituality genuinely capable of setting limits and teaching clear-minded self-restraint” (§105). He urges us onto an “ethical and spiritual itinerary” (§15), a “pilgrimage, woven together by the love God has for each of his creatures and which also unites us in fond affection with brother sun, sister moon, brother river and mother earth” (§92). This way of speaking is an essential part of the change that is needed in our outlook:

In this regard, "the relationship between a good aesthetic education and the maintenance of a healthy environment cannot be overlooked." By learning to see and appreciate beauty, we learn to reject self-interested pragmatism. If someone has not learned to stop and admire something beautiful, we should not be surprised if he or she treats everything as an object to be used and abused without scruple. If we want to bring about deep change, we need to realize that certain mindsets really do influence our behavior (§215).

At the heart of the encyclical we find a profound spiritual teaching. Pope Francis identified the problem of consumerism as an empty heart, which turns to consumption for fulfillment. He returns to the theme of the deep interconnectedness of all creation by citing Pope Benedict: “The external deserts in the world are growing, because the internal deserts have become so vast” (§217). Early in the document, he also joins St. John Paul II in calling Christians to an “ecological conversion,”, whereby the effects of their encounter with Jesus Christ become evident in their relationship with the world around them” (§217) The process entails “profound changes in ‘lifestyles, models of production and consumption, and the established structures of power which today govern societies’” (§5).

How might this change occur? The renewal of this culture is not reducible to policy but is a spiritual task. He summarizes some of the important spiritual work to be done as he endorses Patriarch Bartholomew’s approach to environmental and ecological issues: “He asks us to replace consumption with sacrifice, greed with generosity, wastefulness with a spirit of sharing, an asceticism which ‘entails learning to give, and not simply to give up. It is a way of loving, of moving gradually away from what I want to what God’s world needs. It is liberation from fear, greed and compulsion’” (§9).

I have touched already on what is the most basic building block of our baseline economic attitudes: our tendency to substitute our plans for the world for God’s plans for the world. We are created in the image and likeness of God and hence, “capable of self-knowledge, of self-possession and of freely giving (one)self and entering into communion with other persons” (§65). We systematically exceed our creaturely limitations in our dealings with our three most fundamental and closely intertwined relationships: with God, with our neighbor, and with the earth itself. According to the book of Genesis, these three vital relationships have been broken, both outwardly and within us. We have distorted our mandate to have dominion over the earth, to till it and keep it, and developed relationships of conflict among humans and nature (§66).

Sacrificial love, grounded in the common good, is the only manner of healing this spiritual malaise. Pope Francis writes:

Social love is the key to authentic development: "In order to make society more human, more worthy of the human person, love in social life–political, economic and cultural–must be given renewed value, becoming the constant and highest norm for all activity.” In this framework, along with the importance of little everyday gestures, social love moves us to devise larger strategies to halt environmental degradation and to encourage a "culture of care" which permeates all of society. When we feel that God is calling us to intervene with others in these social dynamics, we should realize that this too is part of our spirituality, which is an exercise of charity and, as such, matures and sanctifies us (§231).

Practices of Cultural Renewal

There are three ways for this approach to sacrificial love to be inculcated in social life: replacing consumption with sacrifice, greed with generosity, and wastefulness with a spirit of sharing. Each of these suggestions for change involves developing the right spirit by which to live, that of generosity.

- Consumption to sacrifice: Francis urges us to begin the movement from consumption to sacrifice. We are called to sacrifice a lifestyle of super-abundance and corresponding waste. The ecological crisis is, he believes, a small sign of the ethical, cultural and spiritual crisis of modernity that must be healed as we heal all fundamental human relationships (§119). We must sacrifice the mindset that keeps the culture of consumerism going at such an unsustainable pace (§161). We must learn to sacrifice the right to consume in a way that cannot be universalized (§50). We must give up the “use and throw away” logic that stems from the “the disordered desire to consume more than what is really necessary” (§123). We must resist the culture of individualism, of the technocratic paradigm, and of instant gratification (§162, §111). Correspondingly, we must turn from a politics of immediate results which will not support a far-sighted environmental agenda and think instead of the long term common good (§178). We must strive for a healthy politics which can incorporate substantial ecological considerations while challenging the logic of present-day culture. (§197)

- Greed to generosity: In urging us to a second movement of our spiritual lives, he calls on us to move from living in a spirit of greed to living in a spirit of generosity. He uses the word greed sparingly but connects it directly to the emptiness of one’s heart: “When people become self-centered and self-enclosed, their greed increases. The emptier a person’s heart is, the more he or she needs things to buy, own and consume” (§204). He often uses such synonyms for greed as selfishness, collective selfishness, self-centeredness, self-absorption, instant gratification, self-interest and urges us to reject a self-interested pragmatism (§215), which threatens to take us along a path to self-destruction (§163). For myself, I believe that most people are still at a remove or two from active destructive greed, but are fully, as Americans, in pursuit of a life of increasing levels of comfort. It seems, however, that the results of such a life are precisely the issues that Francis identifies for us. Francis urges us to leave this self-interested spirit of living and move through sacrifice to a spirit of poverty. This spirit of poverty is necessary to be able to respond both to nature and to the poor in the manner of St. Francis. He reminds us throughout the document that when we can experience all of creation as a loving gift from God we are near to the ecological conversion attitudes that he urges us to adopt (§220). Gratitude and a sense of gratuitousness for God’s love and the gift of creation well up within us (§58) and prompt in us “a recognition that the world is God’s loving gift, and that we are called quietly to imitate his generosity in self-sacrifice and good works” (§220). Both when we care for the environment and the poor by following the little way of love of St. Therese of Lisieux, or when we exhibit love in macro-relationships, whether through intermediate groups or directly in social, political and economic life, we are making our way to a life characterized by the “gestures of generosity, solidarity and care."

- Wastefulness to Spirit of Sharing: The third movement that he calls for in our spiritual life is to replace wastefulness with a spirit of sharing. As we have seen, Francis believes that the lifestyle we are living and promulgating is incapable of being universalized because “the planet could not even contain the waste products of such consumption” (§50). For Francis, the lifestyle that produces such waste reflects a violence in our hearts that is exhibited in symptoms of sickness in the soil, water, air, and in all forms of life. “This is why the earth herself, burdened and laid waste, is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor; she ‘groans in travail’” (§2). He suggests that Mary herself now “grieves for the sufferings of the crucified poor and for the creatures of this world laid waste by human power” (§241). He seems to believe that we ourselves stand in grave danger of being laid waste. In discussing the enormous inequalities that have developed, he states: “We fail to see that some are mired in desperate and degrading poverty, with no way out, while others have not the faintest idea of what to do with their possessions, vainly showing off their supposed superiority and leaving behind them so much waste which, if it were the case everywhere, would destroy the planet” (§90).

In the face of such a devastating critique of our current condition, where does he find reason to hope? Francis finds hope in his belief that a spiritual crisis, such as that provoked by the Babylonian captivity, can lead to a deeper faith in God, who can overcome every form of evil (§74). He points to the gains made by the ecological movement, thanks to the efforts of many organizations of civil society. We have seen his belief that such "community actions, when they express self-giving love, can also become intense spiritual experiences." The many resulting earth summit proposals, whether put into immediate action or not, are evidence of a growing environmental consciousness and can help facilitate the ecological conversion he calls for. Perhaps it is too much even for Francis to hope for that everyone will come to share the vision of the bishops of Japan when they state: “To sense each creature singing the hymn of its existence is to live joyfully in God’s love and hope” (§85). But it is not far from his hopes that each of us can begin to sacrifice consumption, take up a lifestyle more generous to the earth and the poor and live in a more communal spirit of sharing.

In conclusion, Pope Francis' Laudato Si' recognizes the need for creating a culture characterized by an economy of gift, not scarcity, where living out the ecological virtues of moderation, simplicity, spiritual detachment from possessions, and the spirit of peace could guide us in directing the models of production and consumption towards sustainability. Pope Francis believes that we can begin to overcome what he calls the myths of utilitarian modernity, those previously noted myths of individualism, unlimited progress, competition, consumerism, and unregulated markets (§210).

And that is a hopeful message.