John Paul II was a man so morally strict, of such moral rectitude, that he would never have permitted a rotten candidacy to move forward.

—Pope Francis, quoted in The McCarrick Report

This is the sitting pope’s final word on his predecessor from the Vatican’s comprehensive report on former-cardinal Theodore McCarrick. The Holy See’s Secretariat of State, whose task is governing the Church’s temporal matters, published the widely-covered report on 10 November 2020. The comprehensiveness of this unprecedented official document is astounding. It documents the entire life of a well-known and internationally influential person from 1930 to 2017.

It is necessary to look at the report from the perspective of a lawyer, because the text is concerned with institutional memory as well as decision-making by an apparatus of international law, which also happens to govern the universal Church. Furthermore, this ought to be done from the perspective of the rule of the law, because the report has been used to tarnish people both living (Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz) and dead (St. Pope John Paul II).

The accusations against them lack credibility because this report is not about these figures, but chiefly an analysis of what the documented activities of the Catholic Church's institutions bear witness to. Its actual role is an attempt to establish the facts regarding the recorded procedures in ex-Cardinal McCarrick’s nominations (1977, 1981, 1986, 2000, 2005). It also analyzes the decision-making process that went into these nominations at various stages, especially at the most crucial junctures. The decisions were based on this accumulated knowledge, or, at times, in spite of the gathered information.

Therefore, because they were resolved a long time ago, at least two complicated matters are outside the scope of the document.

- The verdict about Theodore McCarrick's guilt was determined by the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith in a separate, already-closed proceeding based on Canon Law. It did not end by just removing McCarrick from public life, nor by merely stripping him of the honor of being a cardinal. This former bishop and a member of the College of Cardinals was laicized. To use a military analogy, what happened to him was like the disgrace of a four-star general being demoted to the rank private and then confined to isolation.

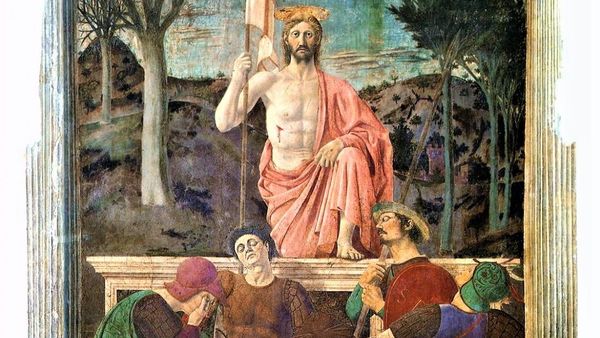

- A verdict on the sanctity of Pope John Paul II—previously confirmed through his beatification by Pope Benedict XVI and later his canonization by Pope Francis—is also outside the scope of the McCarrick Report. Both the beatification and canonization took place based upon lengthy and detailed procedures undertaken by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints. A careful reading of the McCarrick Report will demonstrate that it gives no reason for putting the beatification and canonization causes into question, nor does it discredit the accuracy of their proceedings, nor the credibility of their results.

Due to the nature of the report, which is a thorough study of Vatican documents, the media’s hasty initial verdicts are simply not credible. The main reason for this is not 447 pages one must read in the report. Instead, much time and expertise is necessary to become acquainted with them—as the report is the result of a lengthy and careful internal investigation, which makes its content extensive. It began with the search for, collection, translation, and analysis of all the documents that were available in both Rome and the United States. Numerous witnesses were questioned, including Pope Francis and Pope-Emeritus Benedict XVI.

The investigation concluded with the selection and compilation of the most important quotations from the documents and testimonies, as well as a discussion of their contents using balanced language. The report requires the time commitment necessary for careful reading and reflection. Thus, one cannot seriously speak out about its contents right after its publication as has been done by the media. The declarations that were made shortly after the publication are, at best, declarations of their authors’ prejudices, rather than serious commentary on the report and the facts that it references.

This is not surprising, every crisis in its first phase mostly reveals the intentions of human hearts and what had been hitherto hidden amidst the circumstances that influenced the readers. One ought to maybe prepare a list of those who make statements at such times, but not to remind them what they said later. A lawyer might instead later demand that they make no judgments in similar cases, since they can be considered to be lacking in objectivity a priori. Others might say that it is impossible to engage in a substantive argument with such people, because substantive argument was never their goal in the first place.

Disappointment with the Report

Much to the surprise of many, and despite of what has been reported by the media, the report contains precious little information about Pope St. John Paul II and Cardinal Dziwisz. Perhaps that is the reason why there are attempts to make Theodore McCarrick's nomination as archbishop of Washington, DC in 2000, which paved the way for his becoming a cardinal, the center of attention. Indeed, he became a member of the College of Cardinals the following year.

However, the institutional memory and knowledge about the decision-making process is very instructive at this juncture. The decision itself was not at stake. Its accuracy at the time was confirmed by everything that happened earlier: Theodore McCarrick's streak of success and subsequent promotions beginning with his appointment as auxiliary bishop of New York in 1977 by Pope Paul VI. Its accuracy also is confirmed by what had happened and what would happen later: a subsequent streak of successes, including Pope Benedict XVI’s 2005 extension of his ministry in Washington by two years despite him turning 75 (the age of retirement for bishops).

Although new accusations and evidence emerged in subsequent years, the American prelate continued to be present in high places around the world, skillfully and audaciously succeeding despite the growing doubts about him. He continued to do what he truly enjoyed: traveling. Thus, the Holy See renewed his diplomatic passport in 2009.

In the 1980s and 1990s, McCarrick also offered many services to the government of the United States. He quickly received a prestigious award from then-president Bill Clinton once he became the new archbishop of the American capital. He met with President George W. Bush on numerous occasions. The then-cardinal collaborated closely with Barack Obama’s administration. The Obama administration saw his numerous international travels as the perfect occasion for him to go on delicate missions for his country.

The McCarrick Report implies that he must have been examined by the Secret Services numerous times. Diplomatic matters made him a specialist on Chinese affairs. Beginning with the pontificate of John Paul II, Rome had already begun to employ his expertise on the topic. Pope Benedict XVI dreamed of establishing diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China, which the Vatican's diplomacy definitively succeeded in doing during the pontificate of Pope Francis with the help of Theodore McCarrick.

From time to time, rumors and hearsay about his earlier improper behavior surfaced. This concerned not only the period from 1981 to 1986, when McCarrick was first bishop of Metuchen and then later archbishop of Newark. He maintained that he could at times be imprudent because his openness and kindness could be interpreted in an ambiguous ways. It was said that he shared his bed with young men and went on escapades to the diocesan beach house with seminarians. He claimed that only people of ill will could accuse him of impropriety when there was a limited number of beds.

According to McCarrick, they could sleep on opposite sides of large beds without any innuendo, always in pajamas and always as a group. He never traveled with just one seminarian at a time. He had befriended numerous families during his pastoral work, and he continued his friendships with subsequent generations from them. Lacking brothers and sisters, he treated them as something like adopted relatives. All these rumors and allegations concerned adults.

However, a document directly accusing Theodore McCarrick of homosexuality was finally written in November 2006 (over a year after John Paul II died). It was only then that concrete evidence began to mount. He retired (by no means prematurely) because of this evidence to the Redemptoris Mater Seminary run by the Neocatechumenal Way in Hyattsville, Maryland. Pope Benedict XVI believed that disciplinary actions had been taken, but Theodore McCarrick continued to travel the world. During his visits to the Eternal City, he performed his duties as cardinal in various Roman dicasteries. The Congregation for Bishops expected that he would become less public, but he did no such thing and took advantage of a certain impunity resulting from a lack of overwhelming evidence that would make him subject to Canon Law sanctions. However, in 2008 he was not allowed to participate in prayer with Benedict XVI at the site of the World Trade Center even though he concelebrated Mass and took part in the dinner attended by all the participants of the papal visit. In mid-2009, the congregation characteristically stated the following:

No administrative or judicial process, including any preliminary investigative process, was initiated regarding the allegations against McCarrick. No findings of fact were made by any dicastery and there was never any determination of culpability (340).

Thus, it is unsurprising that earlier in the year the United States House of Representatives asked McCarrick to lead a prayer inaugurating a new session of Congress on 6 January 2009. He even illegally ordained a priest in early May 2013, and thanks to the help of his successor in Washington, Cardinal Donald Wuerl, he succeeded in not having Rome punish him, because Wuerl did not allow him to ordain more priests that same month. In 2013-2017, he received numerous awards, participated in political life by making numerous statements, publicly celebrated Mass and the sacrament of marriage, ordained deacons and priests, and presided over funerals.

All this finally ended in 2017 with a credible accusation of the sexual abuse of a minor. It occurred in the early 1970s, that is, before McCarrick became a bishop in 1977. These were decisive times, as he had already been considered as a candidate for a bishopric in 1968 and 1972. Beginning then, he performed all his functions in the Church in an exemplary manner. McCarrick was devoted to the cause of priestly vocations and had successes in this regard: the number of students grew in the seminarians he oversaw. Always tireless, gifted, bright, friendly, and hardworking, McCarrick was a genius when it came to fundraising and organizing various initiatives.

He also enjoyed great respect among other bishops. People began to feel encouraged to speak up only beginning in 2017. Growing evidence that revealed a culture of intimidation that Theodore McCarrick had created to achieve his personal aims began to mount. His brilliance was hostage to his disordered sexuality, which not only led to the prelate's downfall—still a globetrotter even after he had long retired—but also to the expunging of all his life's achievements.

The Legal Necessity of a Witness

The lack of evidence was critical until 2017, or, at the very least until 2006. Everyone in the Church knows the norm expressed by St. Paul in the First Epistle to Timothy: “Do not accept an accusation against a presbyter unless it is supported by two or three witnesses” (5:19). Yet, this criterion not being met was the case for McCarrick as a bishop beginning in 1977. The requirement for a credible accusation to be put forward by more than one person adopted by the New Covenant had its roots in the laws of the Old Testament. It should be noted that the requirement of multiple witnesses was a new element for the Roman world. However, Roman Law did not immediately bow down to the Christian requirement of more than one witness. The well-known saying “One witness is no witness” began to be used only after the Edict of Toleration for Christians in 313.

The requirement of basing accusations on the consistent testimonies of at least two witnesses, who provide the same cause for the accusations, is an expression of skepticism towards subjective opinions, of the veracity of one person’s account. It attests to helplessness amidst, as we say today, “he said, she said.” Such skepticism is not alien to contemporary criminology, to studies of penal codes, as well as to legal history. The firm conviction that witnesses attest to “what happened” and tell “the whole truth” can result from numerous and diverse factors that lead to inconsistencies or to unconscious distortions of memory. Thus, if there is reasonable doubt, a testimony should not be accepted, nor should legal argumentation be based on it; for example, doubts as to whether there are two consistent testimonies of people reporting to a Church superior about someone committing a grave sin, and, second, doubts involving the credibility and cohesion of the testimonies that are the basis for the accusation.

The Encounter Between Wojtyła and McCarrick

Where do Karol Wojtyła and Stanisław Dziwisz appear in the whole sad story of the McCarrick Report? They appear only twice. They do not appear within the context of the nomination of the auxiliary bishop of New York as bishop of Metuchen in 1981 nor in his appointment as the archbishop of Newark five years later. The study in 1977 consisted of sending a confidential survey to fifty-two people. By that point, the candidate was already a bishop. Thus, he formed a key part of the infrastructure of the Church's hierarchy. If not him, who could be trusted?

However, during his promotion to the rank of an independent bishop, McCarrick's integrity, and the personal skills necessary to perform the new functions, were re-evaluated. A reliable and typical vetting of his candidacy brought new opinions about a person whose only flaw appeared to be that he was a bit too ambitious. Meanwhile, his successful mission in organizing the new diocese of Metuchen quickly led to his promotion as archbishop of Newark in 1986. During both nominations, not the slightest flaw appeared in his candidacy. Pope John Paul II was presented with a document, ready to sign, on the candidacy of a bishop who seemed competent and of the first order.

In the report, Karol Wojtyła and Stanisław Dziwisz first appear in 1976. The archbishop of Krakow visited the United States, and the archbishop of New York was uncertain about his guests’ English. Thus, he summoned Father Theodore McCarrick, who spoke four foreign languages (Spanish, French, Italian, and German), from a youth camp in the Bahamas. In the presence of the Krakow cardinal, he joked that he had to cut his vacation short because of him. He would be remembered thanks to this joke. Pope John Paul II asked if he had finally had some time to rest during McCarrick’s first visit to him in Rome.

A Candidate for Three Sees

Once again, this is a longer story. The dynamic archbishop of Newark became a candidate to lead the Chicago archdiocese, traditionally a cardinalate see, in 1997. It turned out that shortly before he had been already vetted by the Vatican and Archbishop John Cardinal O’Connor of New York to test the appropriateness of John Paul II’s visit to Newark—which then took place in 1995. Nothing unsettling had appeared in that vetting and the pope's meeting with the faithful of the diocese turned out to be a pastoral success.

The Congregation for Bishops, which had a plenary session to consider the various candidacies for the cardinalate see in Chicago, had learned of the rumors and accusations about Theodore McCarrick. However, Cardinal O’Connor stated that he knew nothing about them. He opposed the nomination of the archbishop of Newark for other reasons. According to him, someone who would be capable of dealing with the situation on the ground in Chicago, and its major clergy abuse crisis, was needed there. A former seminarian accused Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, who had died of pancreatic cancer, of having molested him. Ultimately, this accusation turned out to be completely false, but the matter dragged on and received significant media attention, which led to much scandal and caused great damage.

Shortly thereafter, McCarrick was considered for becoming Cardinal O’Connor's successor. At this time, the latter had gotten wind of the gossip and accusations regarding McCarrick. Previously, O’Connor had, on repeated occasions, suggested to Theodore McCarrick that he would have liked him to be his coadjutor bishop with the right of succession. After surgery for brain cancer, which would shortly thereafter lead to the cardinal’s death, he informed the new papal nuncio, Archbishop Gabriel Montalvo, about his doubts. He lacked evidence, but nonetheless wrote a confidential letter about it all. He gave his testimony that concerns could at worst be related to old cases, because there could be no talk of new suspicions regarding the behavior of the archbishop of Newark.

Upon the suggestion of Pope John Paul II, Archbishop Giovanni Battista Re, the Holy See’s Substitute for General Affairs, requested an opinion from the previous nuncio, Archbishop Agostino Cacciavillan, whose mission to the United States lasted eight years. He found no basis for the accusations, but he noted that Theodore McCarrick had never had the opportunity to respond to them. At this juncture, someone else became the archbishop of New York. Pope John Paul II requested that the then-nuncio Gabriel Montalvo check all the “rumors and allegations” concerning McCarrick in the United States.

The nuncio, in turn, requested the testimony of four bishops who had known Theodore McCarrick well for many years. The third bishop mentioned the rumors and allegations, but also stated that none of them were based on substantial evidence. Meanwhile, the fourth bishop wrote the longest letter, presenting McCarrick in the best possible light. He argued in favor of McCarrick’s innocence and defended his behavior, which might seem imprudent only to an outside observer. In his summary of the investigation, the nuncio wrote that he never found any direct evidence. He thought that everything was based on rumors and hearsay. He recommended, however, that the late Cardinal O’Connor's advice, as well as that of one of the three consulted bishops be followed. It would be imprudent to entrust the most important and responsible duties in the Church to Theodore McCarrick.

Meanwhile, Montalvo also received letters from four important American prelates in favor of McCarrick's nomination as archbishop of Washington. The only negative factor they cited was the age of the candidate, who then was almost 70. The candidacy was also supported by the archbishop of Washington DC, who was then preparing for his retirement. When juxtaposed with this letter, Cardinal O’Connor's doubts begin to lose their significance; it begins to appear that the deceased archbishop of New York simply did not want McCarrick to be his successor.

In Rome, Archbishop Re received the entirety of the documentation, and would later request that an opinion be prepared for the then-nuncio Agostino Cacciavillan. The latter believed that Gabriel Montalvo was too much under the sway of Cardinal O’Connor's opinion instead of taking a holistic view of the matter. Neither Archbishop Cacciavillan nor Archbishop Re seemed to doubt the candidate's innocence. However, the latter definitively recommended against giving McCarrick a cardinalate see for pragmatic reasons in his statement: in order to not create an occasion for old accusations to be repeated, which would serve neither the Church, nor the prelate. The pope shared this opinion and wrote by hand: “In voto JPII 8.VII.2000.” Thus, John Paul II blocked this candidacy, which the congregation would not consider during its search for the best archbishop of Washington DC.

It should be added here that all of this happened behind McCarrick's back. Nobody, including the nuncio, had asked him about these things. Every observer can see that this was inconsistent with the requirement stretching back to Roman law: “May the other side be heard as well,” especially as accusations appeared. This basic principle of procedural justice is dictated by the requirements for rationality and lawfulness. It expresses an expectation of ordinary fairness and honesty on the part of the other person. In Acts 25:16, St. Luke references one of the chief priest's statements: “I answered them that it was not Roman practice to hand over an accused person before he has faced his accusers and had the opportunity to defend himself against their charge.”

McCarrick's Handwritten Letter

In response to rumors about the existence of Cardinal O’Connor’s letter (he had never been informed about it, thus many ask how he knew the Holy See received it), Theodore McCarrick decided to write his own letter to the pope. He presented it as an act of desperation: amidst the institutional blockade on his candidacy due to a decision by Pope John Paul II, he addressed the letter to the pope’s personal secretary, Bishop Stanisław Dziwisz. A hand-written letter lacking any familiarity with its intended recipient appeared to be a dramatic gesture. Everyone can read the entirety of the letter in the McCarrick Report. It is well-written, excellently composed, and avoids being a simple self-defense, but it instead mostly demonstrates the author's humility. He declares that he is ready to resign from his appointment as archbishop of Newark if he indeed loses the Holy Father’s trust. The text by him contains a key lie contained in what appear to be painfully honest words:

Your Excellency [Stanisław Dziwisz], sure I have made mistakes and may have sometimes lacked in prudence, but in the seventy years of my life, I have never had sexual relations with any person, male or female, young or old, cleric or lay, nor have I ever abused another person or treated them with disrespect (170).

In fact, as archbishop of Washington, McCarrick consistently repeated the same line to the press: that the rumors circling about him were false accusations. He was a victim. One wonders whether the American press believed him.

Pope John Paul II believed Theodore McCarrick's testimony. What did this mean from a legal point of view? He lifted the blockade on his candidacy and allowed the Congregation for Bishops to not exclude him from their search for the best archbishop of Washington. He was not on the list of three candidates proposed by Gabriel Montalvo. However, the proposal from the nuncio in a given country is only one of the suggestions that is taken into consideration in such a process. There were also the four above-mentioned letters from four American prelates and the members of the Congregation for Bishops, all of whom were up-to-date about the possible candidates.

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith had already stated that it had no negative comments; there was nothing in the documentation that should lead one to be wary of McCarrick's candidacy. The Congregation for Bishops undertook further steps that were typical under such circumstances, at the same time requesting the opinion of Archbishop Cacciavillan, who in turn believed that McCarrick was the best candidate for Washington.

The pope asked the Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Angelo Sodano, who was on his way to the United States, to communicate to Theodore McCarrick that he believed him. On this occasion, Cardinal Sodano did not mention anything about his possible nomination as archbishop of Washington. He indicated that these things should not be linked together. The pope believed in the honesty and purity of the archbishop, who even suggested that he would be ready to resign if he were to lose the pope’s trust. He regained it, but that did not amount to his promotion.

The pope promoted him, but only upon the request of the Congregation for Bishops, which had concluded a careful routine proceeding typical for such cases. Its members were also convinced of McCarrick's moral rectitude. Once again, the congregation seriously considered the pragmatic prerogative, which had emerged victorious amidst the previous blockade of Theodore McCarrick's nomination. Since no evidence was found after such a lengthy search, it was believed that if such rumors and allegations were repeated, the situation would be safe. In a note that accompanied the documents sent to Washington, the secretary of the congregation wrote to the nuncio:

If, therefore, upon his promotion, such rumors were to reemerge, it will be easy to respond to them. The risk that these rumors will reemerge does exist: Cardinal O’Connor, a person of great honesty and seriousness, would not have reminded us of this risk had he not considered it a real possibility. However, now certain that the accusations are false, they can easily be denied (181-182).

The first actual evidence appeared only six years later. Vetting Theodore McCarrick once more in 2005 must have led to a positive verification of his suitability since there were no obstacles to extending his tenure in Washington despite his having reached the retirement age of 75. Pope Benedict XVI extended McCarrick's mission in Washington by two years. Even if more serious evidence emerged, it would have been enough to not initiate any new procedures as before—mostly because of health reasons, since everyone has a right to retire.

Believing a Liar?

And what was Bishop Stanisław Dziwisz’s role? In reality, it was modest. He was in Castel Gandalfo when he received Theodore McCarrick's letter and immediately asked Cardinal James Harvey to translate it into Italian for the pope. That is all. The report also contains Cardinal Harvey's comment that this was an exceptional circumstance and that he had never been asked to do something similar before. Thus, Bishop Dziwisz did not hide this letter from John Paul II. When asked about the whole situation during the preparation of the report, he replied that he had never spoken to the pope about the letter’s contents. John Paul II directly presented Archbishop Re with the decision to no longer block the nomination. The authors of the report attempt to explain the reasons why Pope John Paul II could have believed McCarrick's letter. In the summary at the beginning of the report, they write:

Though there is no direct evidence, it appears likely from the information obtained that John Paul II’s past experience in Poland regarding the use of spurious allegations against bishops to degrade the standing of the Church played a role in his willingness to believe McCarrick’s denials (9).

Arguments are provided by the lengthy footnote #580 on pages 173–174. The footnote mentions an attempt to fabricate a scandal around John Paul II in 1983, and, above all, the pope's careful approach to moral accusations coming from dubious sources, especially those that are not presented to Church superiors. His suspicion was caused by his experience with the communist secret police, which was frequently engaged in provocations and accusations against priests.

Personal reasons for believing someone (or not) can be meaningful to a given decision and a person of interest. But they are not of crucial significance for a procedure of establishing the facts. The procedural problem consisted of a lack of evidence combined with contradictory statements. This principle comes from Roman law and demands that those that claim something and not those that deny it are subject to evidence. This is a requirement of rationality, which must be respected in the name of lawfulness. Thus, it appears as a basic element of procedural justice in all legal systems; for example, in Poland it appears in Article 6 in the Code of Civil Law.

Regardless, the accused had not been asked by anyone, while rumors and allegations circulated behind his back. There is no reasonable way of finding evidence for a negative circumstance: that something did not happen or take place. What remains is the search for a positive statement. In this situation, such declarations as “I was not” and “I did not” play the role of evidence. They can be challenged, but only with concrete evidence. Those that oppose a declaration must present evidence.

Can one not believe a declaration? In all our work in the Church, especially in parish offices, we begin with the assumption that those who make declarations and present facts tell the truth. The culture of suspicion is foreign to us because we will not get far if we give into it. This solution is pragmatic but characteristic of people with strong faith. Either way, they do not lie to us—everyone is responsible for their own words before God. Those that lie to us are lying to God. The Anglo-Saxons say that those who cheat others in reality cheat themselves.

In the American legal system, even an informal accusation of dishonesty in an ordinary conversation can easily end up in the courtroom. The case will be difficult, because a lie must be proven, and those who say something, not those who contradict, are subject to evidence. In American culture relying solely on someone's word is the absolute basis for a proceeding. Equally firm is the almost “eternal” lack of forgiveness and ruthlessness, and the assumption of implausibility, if someone is caught lying but even once.

Suspicion is foreign to the Vatican report, which presents documents in a completely open way. Some criticize this openness or are offended by it. They claim that suspicion was foreign to the entire system of proceeding during times of decision-making: in 1977, 1981, 1986, 2000, and 2005. Those who try to question the sanctity of Pope John Paul II must be disappointed with the McCarrick Report. There the pope appears to be a prudent, careful, and responsible supervisor who requests an additional investigation, but also has confidence in the institution he leads, as well as the congregations that assist him in his work around the world and has respect for his collaborators. John Paul II was the first to request an investigation, which was the only one of its kind until 2006, or, more precisely, 2017. The report also contains no information that would incriminate Cardinal Dziwisz. From the perspective of a lawyer, there is nothing that could discredit either person.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This is a slightly truncated version of the Polish original published by Teologia Polityczna. Our sincere thanks go out to the editors of Teologia Polityczna for giving us permission to publish this translation.