Conor Dugan (CD): Can you tell our readers a little bit about yourself? Where did you grow up?

Bishop Perry (BP): I was born and raised in Chicago until age 15 when I entered St. Lawrence High School Seminary, Mt Calvary, WI. I am a cradle Catholic. Catholicism is from my father’s side. My mother was a Baptist until her conversion to Catholicism when I was about 17 and in seminary. Catholicism stretches back to my father’s side for several generations post-slavery. From father’s side of the family we were one of several families from a huge farm in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. My great-great grandfather moved from Murfreesboro to Nashville to work in the mills, and that’s where two of his children became Catholic, my paternal grandmother and her brother. How or why they became Catholic I don’t know, but one of the sons of our great patriarch produced a granddaughter who became a nun and his daughter had a grandson who became a priest, which is me.

CD: Did you have siblings growing up?

BP: There were six of us. My parents and two other siblings are deceased.

CD: And did your family come up to Chicago as part of the great migration of African Americans from the South to North?

BP: Yes, they did. My parents married shortly after the war. My father had been in the army and was discharged after the Japanese surrendered in 1945 and at that point, a lot of people were coming up from points south to the North because that’s where jobs were found. In the South, there were no jobs after the war, not many before the war and certainly not after the war. So yes, they were part of that great migration. My folks married in 1946 and came up to Chicago at that time and started their family.

CD: How did your family instill the faith in you?

BP: My father taught us our Catholic faith and our prayers. A Bible always sat on the top ledge of my parents’ bed. He read it every day. Dad taught us our prayers and had us recite our prayers to the delight of guests who came to the house. Dad was proud of his Catholicism. I attended Mass every day as required by my Catholic elementary school rearing. I was an altar boy and was a member of a praetorian of altar boys who served the nuns’ early convent Mass, weekdays, at 6AM.

CD: How did you discern your vocation?

BP: My inspiration for a religious vocation came from the nuns who taught us and the priests who served our parish. They were strong people and exuded the finest examples of priestly and religious life that could stir the heart of a budding teen like myself. I kept up correspondence with a number of them over the years until their deaths. Plus, annually we had vocation recruiters visit our schools to do vocation pitches to the pupils to think about possibly serving the Church as priests, sisters, brothers. I harbored a sensitivity for things religious from earliest childhood.

CD: Can you tell us a bit what it was like growing up a Black Catholic? Did you attend a historically Black parish?

BP: We moved as a family several times growing up as the family increased in size. The parishes and parish schools we attended varied in racial composition; some were all white, others were predominantly Black. All my life I have lived with both communities.

CD: Tell us about your pastoral experiences as a priest. Where did you serve?

BP: Upon ordination in 1975, I was assigned as associate pastor at St Nicholas Parish, Milwaukee, for a year and a half before being assigned to the Archdiocesan offices specifically in the Tribunal Department. During canon law studies and my work in the Tribunal throughout the years I assisted pastors in various parishes as a weekend help-out priest with the Sunday Mass schedule. In 1995 I was assigned pastor of All Saints Church, Milwaukee, and was there for three years until the surprise appointment to transfer to Chicago as an auxiliary bishop in assistance to Cardinal Francis George, O.M.I.

CD: Can you tell us how you learned about that appointment?

BP: I answered a telephone call on the morning of April 28, 1998, 6:30AM just before my morning Mass. As it turned out the caller was the Vatican’s representative in Washington DC, Archbishop Agostino Cacciavillan, who required my statement of acceptance on the spot as well as my confidentiality about the appointment until it was officially announced by the Vatican on May 5. I was not allowed to speak to my parents about it until the night before the official announcement.

CD: What was your relationship with Cardinal George like?

BP: My relationship was as a cleric in the rank of bishop in assistance to the Archbishop of Chicago. It was a formal relationship shared with six other auxiliary bishops dominated by the intensity of pastoral oversight and administration of 75 parishes in Vicariate VI. There are six vicariates in the Archdiocese of Chicago featuring the vast expanse of Chicago. He respected me and I respected him. We shared many ideals about Church and its place in the world. I was most impressed by the Cardinal’s sensitivity and his humility despite his brilliance and intellectual acumen. He could be moved visibly by the plight of poor people. I was always mesmerized by his sermons and other talks.

CD: You made a poignant statement about the death of George Floyd. I was struck because it was different from many of the statements we have heard from various quarters. You spoke as a bishop, a priest, an African American. It was poetic and called for prayer in the face of this horrible act. Can you tell us a little about your response and why you expressed it in the way you did?

BP: I have a predilection for history, I taught it to high school students in my earlier years. I relish documentaries and historical exposes. Most of the responses about George Floyd’s tragedy that appeared in print, and some vocally, appeared to be in the same vein—outrage toward law enforcement. I have a deep respect for history and believe we are challenged by historical events of the past and present; events that describe the foibles and mistakes and great sins—that which must be dealt with, reconciled, revisited—as well as the glories and accomplishments of the past and present that must be celebrated so that the future can chart a better course. The questions I posed in my statement were designed to elicit the answer “no” each time on the part of the reader; in this instance, how has the African American male been respected and disrespected.

CD: Were you trying to come at it from a different perspective? To me, it's hard to put into words, but your statement just seemed different from a lot of those that I've heard.

BP: From my appreciation of history, I see that particular event with George Floyd and many others akin to it to be all part of a historical trajectory that goes all the way back to slavery. And I think in order to understand this tragic event, you have to look at it from an historical perspective. Obviously, there are concerns about law enforcement. There are good police and there are bad police. In every profession you have good and bad. There’s no doubt about that. But I try to reconcile the present with the past in order to somehow understand the present and somehow see clearly what tomorrow might and can be.

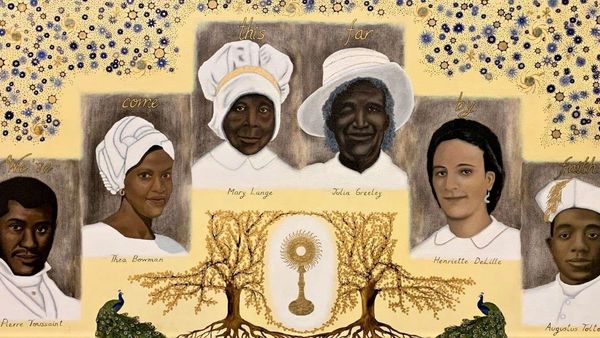

CD: July 9 marked the anniversary of Venerable Augustus Tolton’s death in 1897. Fr. Tolton was born a slave and ordained a priest. You are the postulator of his Cause. Can you tell us a bit about him?

BP: Augustus/Augustine was rescued from slavery on a farm in Northeast Missouri, a slave state, when he was nine years old, by his mother who sought freedom for herself and her three children in the midst of the Civil War (1863). She attempted the escape shortly after the death of the man who owned her and her children. Accosted at one point by Southern bounty hunters but eventually rescued by Union troops and crossing the treacherous Mississippi River she landed in Illinois, a free state, and thereafter navigated the choppy waters of racial acceptance in vogue at that time. The word “no” was spit in Augustus’s face more often than not: from attendance at several Catholic and public schools in Quincy, Illinois, to being denied entrance into seminaries in the United States due to his color and background, to being told as a priest he was not to minister to whites even those whites who snuck into his church for Mass and the sacraments.

Unnerved by his success pastorally with all kinds of people fortunate and unfortunate, fellow priests and ministers of other churches launched a whispering campaign against Tolton until he was told by his bishop to leave town. The Archbishop of Chicago, Patrick Feehan, welcomed him to come and minister to a fledgling group of Black Catholics who were worshipping in the basement of St. Mary’s Church, downtown. His congregation eventually grew from thirty to about six hundred; he was given permission to commence with the construction of a parish church for Blacks in Chicago, a church never completed, due to lack of finances. Father Tolton ministered to St. Monica Church for Blacks until his untimely death in 1897 at age 43.

CD: What can Fr. Tolton teach us today about how to handle the question of racism?

BP: Being first a Christian and a Catholic and having in his young years the models of nuns and priests who were champions of social justice, Tolton transferred the same qualities to his own pastoral ministry. His church doors were open to white and Black alike which eventually got him into serious trouble. The lines of racial demarcation were set rigidly in the nineteenth century. But Fr. Tolton believed the chief mission of the Church was to unite people of every race and apply dignity to every person. His magnetism, his wisdom, his pastoral zeal saw Tolton draw men and women of every skin tone together under one roof for worship—a novel idea for that time that disturbed some folks.

Father Tolton was a very open and kind-hearted soul. And he experienced in his boyhood and all through his priesthood both sides of the Church, the negative side and the positive side. And yet, at the same time, he believed the Church was much larger than the situation in which he was born and raised and lived and pastored. Being the kind of person that he was along with the appreciation he had for the priests and the nuns who tutored him and counseled him, he transferred much of that into his own priestly ministry. And that is what endeared him to many people of his time, both white and Black.

Even though Augustus lived in a society and Church that were for the most part unready for that kind of ministry—namely a ministry of diversity without differentiation or discrimination—he was an open and gifted individual and that is why white people snuck into his church on Sunday and they were not supposed to be there. People, essentially, are attracted to goodness most of the time.

But those same virtues on his part have not gone out of style. We are still trying to grab onto what that means for today because we live such socially demarcated lives. White and Black do not know each other. We seldom experience each other, so there are these fears about the other. And sometimes those fears can erupt in something awful, as we have seen.

CD: Father Tolton seems to be a living example of a theme expressed by Joseph Ratzinger and Mother Teresa that success is not a Gospel category, that we are called not to be successful but faithful. First, do you think that is an accurate assessment? Second, what can his example of faithfulness in the midst of adversity teach us?

BP: Depending on who is doing the reading or the assessing one can pose an argument that Jesus Christ was unsuccessful in his mission for various reasons. It all ended with him being subjected to the kind of death reserved for conquered peoples and other undesirables— crucifixion. But the Lord was faithful to the will of his Father even though it meant Him having his body ripped apart, bleeding excruciatingly for the redemption of mankind. Tolton’s suffering service can also be seen as echoing elements of the suffering Christ.

Somehow, the work of redemption required this self-emptying, this rejection that leaves the best among us spent on behalf of others. Secondly, faithfulness is one of the definitions of God. God expects us to mirror him if we will live with him forever. Faithfulness is one of the higher virtues. No one has accomplished much without being faithful to the task, to others, and therefore to God. Fidelity is tried by adversity. Augustus Tolton was no Moses nor a Frederick Douglass nor a Martin Luther King. But people recall his legacy as a gentle pastor, one who knew pain and rejection and returned nothing to his enemies except Christian regard and care. This is holiness in the Christian imagination of things.

CD: What would you want readers—especially white Catholics—to know about the Black Catholic experience? In a talk you once said, “African Americans have a complicated history with Catholicism.” Can you unpack that for us?

BP: Black Catholics are an enigma for many. It is commonly perceived that Blacks are Protestant in this country, while Catholicism is for Europeans and their descendants. Well, whites are probably responsible for this myth because, for the longest time, in this country, Blacks were slaves and servants and laborers for bishops, priests, and religious and, once emancipated, were shooed away from Catholic Churches and told to go elsewhere. Some Blacks went to Protestant churches for this reason, many Black Catholics converted to Protestant traditions because of what they experienced from the hands, words, and gestures of whites. Stories are legion about was said to Blacks who stepped into a Catholic Church or who dared apply to seminaries and convents. The mindset of that time refused any notion that Blacks could be priests, sisters, brothers or have leadership positions in the Church. If received, African Americans had to forsake their cultural experience in order to adjust to the dominant culture of our institutions similar to slavery’s policy that enslaved Africans forsake their names, religious experience, and customs. The dominant culture exhibited no interest in the Black experience and no desire to learn of the pathos and beauty of Black culture. The official Church has given mixed messages to African Americans over the stretch of a very long time.

CD: I had the chance to get to know the late-Bishop Leonard Olivier, an African American auxiliary bishop of Washington DC. I remember him telling me that as a boy in Louisiana whites would spit on him as he went to communion. As he told me this, I thought, “And, yet, you still became a priest? You maintained your faith!” My sense of Black Catholics of his generation and a generation younger is that this sort of experience was not uncommon. For instance, a Capuchin priest friend told me of an African American woman who, every Sunday, sat in the front row of the parish he helped out at in Washington DC. He finally asked her why she sat in the front row every week. She replied, “Because I can.” It came out that she had attended the parish when it was segregated and she could not sit in the front row. She had been limited to another Mass or pews in the back. How do you explain this great faith of men and women like this, when their own brothers and sisters in the faith showed them such contempt? Have you experienced similar experiences as a Black Catholic? Did you witness your family suffer from such racism in the Church?

BP: I recall my paternal grandmother mentioning back in the day when Blacks, in those places where they were even allowed to come inside a white parish church, had to sit in roped-off rear sections of the church or in balconies. It was not permitted to kneel at the communion railing with whites and therefore Blacks could not receive Holy Communion unless the priest brought it to them. If he did not bring it to them, they did not have the benefit of receiving Holy Communion that Sunday. Grandma eventually left the Catholic Church and was not reconciled with the Church, unfortunately, by the time she died at the age of 92.

CD: Did you personally experience racism in your parishes, especially the predominantly white ones, growing up?

BP: To a slight degree. I do remember one parish where I was in grade school that was predominantly white. They never allowed me to be an altar boy. I didn’t become an altar boy until our family had moved and we had joined a predominantly African American parish, where I became an altar boy. That sticks in my memory, but nothing more dramatic than that.

CD: Did you have any examples of African American priests growing up?

BP: The first African American priest I met was a Divine Word Father who I visited and corresponded with regularly until his death a couple of months ago. He was in his upper 80s. I was in the sixth grade when I first met him. He was a kind man. He was a philosophy teacher in their seminary at one point in his career. But other than that, we didn’t have many images in those days of African American clergy because there were but few around.

CD: Did you know about Father Tolton growing up?

BP: Not until I was a young priest.

CD: You spoke of your experience of not being allowed to be an altar boy. How in the midst of that do you say yes to a priestly vocation when you’ve seen your co-religionists treat you in a way that’s contrary to the Gospel?

BP: I guess it’s an understanding, similar to Father Tolton, that the Church is much larger than its members in what it stands for and an understanding that the Church has saints and sinners. Even the Lord spoke of that, the parable of the weeds among the wheat. And I think that’s been pretty much the outlook of African American Catholics over many, many years. They know there’s a truth to the Church that cannot be, how should I say it, defied. And there’s some people who are representatives of that truth and others who are not. Where you don’t find the truth, then you pick up and go elsewhere to see if you can find it.

CD: You are the chairman of the USCCB’s subcommittee on African American Affairs. Can you tell me what you do in that role? What does the subcommittee undertake? Do you have new initiatives in light of the events in the last month?

BP: The African American Affairs subcommittee is one of several under the umbrella of a standing committee for Cultural Diversity In the Church of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). Other groupings would be Asians, Pacific Islanders, Latinos, Native Americans, Migrants, Refugees and Travelers. The purpose of this standing committee and its subcommittees is to keep the bishops abreast of the contributions, needs and issues impacting these various groupings of Catholics who for various reasons satellite our society. In light of current events, our subcommittee on African American Affairs published a document listing ways in which dioceses and parishes can educate/re-educate the Christian faithful to tackle the complex problem of race in our Church and in our society.

The US Bishops have published about ten documents/statements dealing with the impact of racial tension on society and the Church going back to about 1958, the most recent of which was Open Wide Our Hearts in 2018. Our subcommittee has been cooperative with workshops around the country, on this topic and others related to it, participating in listening sessions of Catholics telling their stories. We also have as goals and objectives, initiatives nurturing vocations to priestly and religious life in the African American community, and supporting marriage and family life. And we stand to offer resources to parishes and dioceses with their own local programming.

CD: Do you sense that among some Catholics, maybe white Catholics, conservative Catholics, there’s maybe a denial or just not a full recognition of some of the issues that are still present with respect to race?

BP: In the American society in which you and I live, individualism and privacy in my own backyard are rather heavily guarded realities. We are not terribly inspired to go outside of ourselves. We create our own private sanctuaries and let people in that we choose. Our collective responsibility for creating community is less appreciated. We don’t like people telling us what to do and who to befriend, who to interact with. That’s the American psyche and it’s an obstruction to dismantling our fears about people of color. All this arises out of ignorance and the lack of experience with other people because we don’t want experience with other people. We’re satisfied where we’re at. We’re very comfortable and we want to make the best of a comfortable situation. We don't want to be bothered out of our comfort zones. We’re a society, a culture of choices and our sense of choice is rather keen. This feeds into the penchant for preferring a white environment and thinking that it is the best environment, the more profitable and secure environment.

CD: How would you, if you were to talk to a Catholic layman like me, begin to break down this hyper-individualism, this unwillingness to go out and dismantle these barriers to knowing it's not just Black Catholics, but Latino Catholics, Catholics that maybe don’t look like us or don’t necessarily come to our parish. What sort of advice would you give? Obviously prayer to start, to know the Lord’s will, but what else?

BP: I encourage people who consider themselves Christians to schedule diversity in their life, to examine their lifestyles to notice who it is they hang around with beyond just who lives next door to you and who are your relatives. It takes courage to once in a while attend a church with a different cultural group, to somehow take in the beauty of a people, their culture, their experience and see how it might complement your own life. Monoracial parishes are odd from a Christian perspective and certainly from a Pentecost perspective. From a Catholic perspective, we’re expected to do a little bit more than the average citizen when it comes to breaking down barriers.

Check out who your children hang around with. Are all their friends white? What do they see happening in school with other kids of a different racial or ethnic background? What’s happening there? How can we raise young people to become ambassadors of friendship and goodwill for the next chapter of society? If I was a married man, I wouldn’t want my kids hanging around one race all the time, all African Americans. I would search out a variety of experiences for them, not only here, but around the world.

CD: In the late 1990s and early 2000s, St. John Paul II led the whole Church in a purification of memory. Do you think we need to do something similar as American Catholics? Given some of the things you are telling me that Father Tolton and other African American Catholics endured, would that be a helpful exercise?

BP: I think it certainly is a helpful conversation or maybe even a course or two here or there to understand what has been the history, not only African American history, but other people who have in any way been marginalized. Why is the world diverse? Why was Pentecost a diverse experience proffered by the Holy Spirit? The Holy Spirit was certainly the director and the producer that day. Why did we lose that template somewhere along the line? Why did nationalism or nativism become pseudo-religions for us? All of that stuff can be delved into and it presents some interesting conversation, I think. But you have to have interest in it, to go beyond yourself in order to do something like that. Once the appreciation of history takes place, we move into a reconciliation service and storm heaven with our regrets and our resolutions, an acknowledgment of what we have done and what we have failed to do.

CD: Southern Catholic writer, Walker Percy, wrote in one of his novels that slavery was America’s original sin. It seems like that is an apt metaphor for the effect that slavery and racism have had and continue to have on this nation. Just as original sin wounds, America seems to be wounded by the institution of slavery, even to this day. Can you give us your thoughts on this idea of slavery as America’s “original sin”? How do you see the effects of this “original sin” continuing today?

BP: The social sins of the past carry generational consequences for sure. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 signaled a new day, a new society for the nation and the African American population in particular. Folks thought these laws mainstreaming Blacks in American society would foster a new deal, a new reality. Certain barriers were broken down that heretofore impeded people. Our educational attainments were on the rise, economic improvement and opportunity were on the rise for some.

But, similar to the tumultuous Reconstruction period in the wake of Civil War, there were and are still elements in American society that are intent upon reversing course. Spatial racism is still apparent in housing. Disparities are obvious in health care, incarceration, the arts, and the job markets. Folks have a sense that what was once thought to be gains has stalled.

Communities where African Americans live for the most part are suffering disinvestment. Banks and grocery stores are not found in swaths of our neighborhoods. Poverty is quoted as being two and a half times that of whites as evidenced by the destitution we see around us in blighted neighborhoods, families being unable to achieve a modicum of existence and see their children accomplish the American Dream. Many Black neighborhoods spell misery.

All the while, African Americans die early having suffered disproportionately from cardiac disease, diabetes, respiratory illnesses and various cancers. In all this African Americans are profiled as prone to criminal acts and are to be treated harshly if confronted by law enforcement who avail themselves of humiliation and harassment tactics. African American males are no better off compared with white males than they were forty years ago. So, the sinful system with its sinful structures continues from one generation to the next and does not seem able to remedy itself—this is the original sin. Social structures maintain misery for a group of people.

CD: Related to this, the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church §119 says that the “consequences of sin perpetuate the structures of sin. These are rooted in personal sin and therefore, are always connected to concrete acts of the individuals who commit them, consolidate them and make it difficult to remove them. It is thus that they grow stronger, spread and become sources of other sins, conditioning human conduct.” If I am not mistaken, this idea of “structures of sin,” at least as a term, was introduced by Pope St. John Paul II. Can this concept help us to understand the ravages of racism upon America? Can this give us a key to understanding how racism still affects us even if individuals are not necessarily guilty of racism?

BP: You just gave a definition of “original sin” here. But no one believes in original sin today. And, consequently, no one can imagine themselves being racist. There is a Jewish saying that goes like this: “All are not guilty but all are responsible.” This is a healthy approach that can forge a breakthrough towards better understanding of what is going on around us. Until some folks take responsibility then nothing will get solved. If we acquit ourselves of complicity regarding the conditions of marginalized races and ethnicities in our society, then nothing will be resolved, reconciliation will never be achieved because I have absolved myself of any responsibility with the notion: “I never had no slaves!”

CD: How do we take those steps of responsibility? You used that beautiful Jewish saying that all are not guilty, but all are responsible. At least my perception is we live in a culture where there’s a lot of talk, but not a lot of action at times and I guess I would love to hear concrete steps we as Catholics can take to take that responsibility.

BP: Certainly, those recommendations that we made out of our subcommittee is a start. It takes small steps because you can’t overturn 400 years in four years, that’s for sure. So much has happened and so much has been done. But consciousness, growth happen gradually and if we could take those recommendations of the bishops’ committee and there probably are some others, too, that people can come up with and put them into action, we can begin building bridges, ameliorating the emotional and visual dissonance experienced when a person of dark skin enters our space.

I don’t know about the rest of society, but certainly as Catholic Christians we could take one of the pastoral statements of the bishops. There are at least 10 of them since 1958 about racism and diversity and multiculturalism and use them as adult education prompts. You’ve got to start somewhere. That whole notion of collective responsibility is a very Hebrew notion. We Americans don’t understand community.

CD: George Floyd’s killing has set off social unrest. In a radio interview, you described this as our “simmering unrest” and that Floyd’s death had unleashed a “powder keg” that was previously “simmering”. The powder keg has been set ablaze. How would you diagnose what we’ve seen since George Floyd’s death? What was this “simmering unrest” that has now boiled over? Your statement on George Floyd’s death seemed to acknowledge this simmering unrest that was there under the surface.

BP: There are people who can’t “breathe” in our society and are being smothered. We are faced with the unfinished business of race in this country, the unsolved issues of poverty, opportunity vs lack of opportunity. We hardly give second thought to the stratified society we live in, thinking it to be normal—if you people would just pull yourselves up by your bootstraps. But untold numbers of people, blacks, browns, Natives ,and some others, have no boots with which to pull up straps! Structures in a materially rich society have left large numbers of peopl disenfranchised from life such that they cannot “breathe” the air of a free and prosperous society like ours.

While we are all the same, humans who bleed, sweat, and cry tears, the differences allowed to fester among us are huge. And some insidious factions are intent on keeping it that way. COVID-19 couldn’t have come at a more inconvenient time, upending our lives; several deaths of African Americans at the hands of law enforcement couldn’t have come at a more inconvenient time; those already living on the margins due to lack of employment, underemployment, and other pressures domestic and otherwise, plus a considerable number of other people, were ineligible for the $1200 stimulus grant of the government.

So, with people out of a job having to care for children, put food on the table, pay mortgages and rents; add to this a series of illogical deaths of Black people at the hands of law enforcement, adding to the list of such injustices that have crowded the headlines in recent years—the powder keg was ignited. All this registers to the Black community that we are people who lack the respect of the society within which we live, that fundamental social change with concerted attitudinal shifts have not happened. We are ordinary people eking out an existence like everyone else with all its struggle while plowing through a gauntlet of askance looks, unwelcoming gestures, and ill-stated and awkward words made in reference to us.

For the longest time, going back generations, Black men, our fathers, grandfathers, and great grandfathers, were and are largely invisible in our society except for the football field and basketball court. Otherwise if Black men get too close then society freaks out by calling the police on them—law enforcement and others postured to issue deadly force upon sight for what appears the slightest suspicion weighed heavily against us by reason of the color of our skin.

CD: Is there a danger that we take an approach that ends in a new sort of separatism or a new pitting of the races against each other—a situation where we don’t break down the barriers, but we erect different barriers?

BP: It’s always possible. It depends on who is at the table, who is in the room with the conversation. If people entering the room are of a defensive posture or feel like they’re being accused of something, no one likes to be accused of anything and no one certainly wants to be called a racist. Then you can foment further separation and division and a breakdown in conversation.

But if people on both sides come into the room and they want to learn from each other, first of all admit that I am ignorant and there’s much more I can learn and that I may not be guilty of something, but as a Christian I’m responsible for making this world a better place, then we have something to work with. We have a platform from which to proceed. We don’t want people to be defensive. We don’t want to accuse people of anything especially if they haven’t done anything wrong. But we’re all victims of our own environments for good or for bad.

CD: How you would begin to convey your experience as an African American Catholic to others. What would you want people to know? You are 72 years old. You were, if my math is correct, just a few weeks shy of your twentieth birthday when Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated. And while you were born in the North you were born when Jim Crow Laws and segregation were officially very much the norm in large swaths of America and unofficially throughout America. You have seen the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. You are a priest, a bishop for over 20 years. It seems to me that you can offer a unique perspective. How would you begin to share that perspective with others?

BP: I grew up in the 1950s. I was in college seminary in the 1960s. The notion of civil rights was just starting with the desegregation of schools leading to the famous 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education; institutions, schools, jobs ran the gamut of acceptance to no acceptance to outright discrimination against Blacks. In the 1960s some famous Catholic bishops in places like St. Louis, Chicago, New York ordered desegregation of parish schools. As a kid I witnessed the white-flight from neighborhoods, we saw shady real-estate maneuverings to keep Blacks out of white neighborhoods, racial turnover and loss of childhood friends whose families moved away.

In the 1960s things took on a serious tone with the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy and adjoining riots across the nation akin to today’s unrest in our cities. In seminary I was always among less than a handful of African American students—and the same was true later as a priest. African Americans were always considered a curious situation in the Catholic Church, thought to be essentially Protestant in background and manners.

For the most part, my life has gone smoothly. I was educated, formed by a religious community of the Capuchin Franciscans who have harbored a social justice vision to their various ministries here and in Central America and the Middle East. They have positioned themselves for the longest in Latino and Black parishes in the cities like Chicago, Milwaukee, Saginaw, Detroit. They were interested in recruiting me to apply to their high school seminary to begin with. Being a priest and a bishop might position me on the shelves of prestige. But it also leads, sometimes, to serious misreadings about me by certain people. Some don’t or can’t believe that I am African American or I am thought to be from some other exotic place on the earth and am here as an immigrant!

This is because most whites have never rubbed up against Black Catholics and don’t see Black priests or religious—the few that there are. This has always intrigued me. Several times walking into church sacristies to confer sacraments with my white Master of Ceremonies, not the wiser, parishioners immediately gravitate around him thinking he is the bishop and I am the driver—until they see me start to put on my vesture for the ceremony, then their jaws drop! We laugh about it. So, I get reactions from both sides of the racial spectrum indicative of the misreads we suffer from day-to-day. From my position as a bishop, however people view me, I feel nonetheless the pain of my people and wish I was a mega-wealthy individual to effect some structural change to people’s lives.

CD: And Black men are still having experiences like you describe now, right?

BP: Yeah. I’ve had seminarians tell me, some of our seminarians are from Africa, being stopped by the police in the village where our seminary is, asking them who they are, where they are, why they’re here, what are you doing, hardly believing that they are seminarians down the street. The seminary rector had to intervene with local law enforcement a couple times. They wouldn't pull a white kid over to ask him the same questions, who are you? Why are you here? Sure, tell me another story that you’re a seminarian. So yeah, it happens. It happens today.

CD: The Catholic Church seems to have significant resources to engage the question of racism. The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church states that “the dignity of every person before God is the basis of the dignity of man before other men. Moreover, this is the ultimate foundation of the radical equality and brotherhood among all people, regardless of their race, nation, sex, origin, culture, or class” (§144). To be racist is contrary to our Christian faith. How do we as Catholics make this known in our parishes more broadly in our society?

BP: The topic of race is the most difficult topic delivered in the church pulpit. It rankles people to their bones. For Catholics who ask this or similar questions, I recommend that parish priests and other ministers should be busy about scheduling diversity in the parish community. I encourage Catholics to worship occasionally in a parish of a different ethnic group to break through the racially divided spaces we live in and to imbibe a sense of the worth, culture and beauty of a people. I encourage also reading books and articles on the topic of race and its treatment in America and the challenges faced by people of color particularly those most marginalized and to select one of the pastoral letters on racism issued by the US bishops for reflection and conversation.

Parishes, colleges should arrange small group opportunities for people to share their feelings in midst of news and commentary about vulnerable populations and law enforcement. Encourage participants to reflect or share their own upbringing regarding comments they picked up from the home, from parents, individuals, media and entertainment, even practices of the Church about the merits and demerits of certain groups of people made to be “the other” and ask themselves, “how have I knowingly or unconsciously made this formation part of my world-view?” Lastly, I encourage inquirers to speak up when they hear about or witness a person, white, Black, brown, Asian, Native being mistreated or treated unfairly. These are initiatives that can foster genuine change in society.

CD: The Compendium also states that in “the definite witness of love that God has made manifest in the cross of Christ, all the barriers of enmity have already been torn down (cf. Eph 2, 12-18) and for those who live a new life in Christ, racial and cultural differences are no longer causes of division (cf. Rom 10, 12; Gal 3, 26-28; Col 3, 11)” (§431). The Church calls all of us to the work of “restoring and bearing witness to the unity lost at Babel” (§ 431). How do we as Catholics work to be this source of unity and harmony in our societies? Is the Church’s call different from what we are hearing from the secular world with respect to these questions?

BP: The Church’s call to be a leaven in society and a light in the world is an evangelical summons that recognizes how Good Friday is incumbent in these efforts. Our efforts to build bridges, break down walls, should as far as possible be devoid of political expediency and have only as a goal the realization of the kingdom of God in some semblance before the Lord returns. The scriptures speak for themselves. The bishops say all the right things about these topics. It’s the implementation of these topics in the soil of people’s lives which is at stake.

If the pulpit never evidences any treatment of these complex issues. If the bishops’ counsel is ignored, if diversity has no trace in our lives and in our churches, then the problems will continue and the tears will keep flowing.

CD: On this point, many Catholics are uncomfortable with some of the responses they’ve heard and witnessed to George Floyd’s murder. They recognize the evil of his murder, recognize that racism is contrary to the Gospel, but feel that something is off about the response many in the secular word are giving. Do you share this concern that some of the secular responses are missing an important piece of the truth?

BP: The secular world is forced to think in terms of rights and laws, poverty quotients versus the stock market, political victories vis-à-vis constituencies and the like. The secular sphere cannot speak of the moral grounding of these issues much less their evangelical summons found in the Gospel and the Church’s social teaching. Responses to Floyd's murder can be found disjointed if you have never experienced what George Floyd or his loved ones experienced. If empathy is not apparent in our responses, if we have never walked through a Black neighborhood or interacted with Black people, worshipped inside of a Black church, if we have never delved into responsible literature that describes the disparities, then the secular responses or even some responses of Christians will not be on target and may well be outright erroneous.

CD: It seems that we as Catholics have something unique to offer in response to the Social unrest and righteous anger that has been unleashed by George Floyd’s death. Do you agree? What is this unique response? What would this look like? Does this response involve serving as a source of unity and bringing racial harmony?

BP: The Catholic Church in this country has a huge compendium of suffering experiences of the various groups who immigrated to this country. Each has a suffering story to tell. If we could assemble in the same room and tell our stories we would discover how much we have in common. In many instances, these various peoples had only their Catholic faith as a resource for survival. The difference with Blacks is that our ancestors were dragged here in chains involuntarily and not compensated for their labor or their misery and Blackness has not been quite processed in the world-view of the Euro-American experience. Dissonance often surfaces when a dark person enters white space and some awful things can happen as a result, as we have seen recently happen time and time again. Racism is not just a black-and-white issue. The inequality that haunts human life is an historical penchant of one group over another. It happened in the Balkans. It happened in the Middle East between Jew and Palestinian. It happened in America between white settlers and Native Americans. It happened between Nazis and Jews in World War II Europe. It happened between Britain and Ireland. One group stepping on the necks of another group. We have a penchant for making others suffer so that we increase while making sure others decrease. We can debate about which human group has suffered more than others. But, we all have suffered at the hands of each other.

CD: I am struck that you talked about how each of us has a suffering story to tell and that might be a place where people could start or find common ground. The cross has been part of everyone’s life. Is that what you're pushing at?

BP: Yeah. Exactly. Our ancestors came to this country with varying sagas and narratives that weren’t pretty. And we still don’t know a lot about those stories. We hear what was done to the Irish. We hear what was done to the Italians and the Slavs. We know what’s happened to Latinos and Africans and so forth, but do we appreciate those narratives, those stories, can those stories provoke us to tears, what can they tell us about the stamina of a people, the resolve of the people to grab onto the virtues of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, peace and well-being, religious freedom, all these good things. We share the pursuit of these things in common. We came here under different circumstances and under different historical periods, but we share many of the visions and dreams that any other human being shares.

CD: That seems like a place where diocesan or parish efforts to bring parishes together—where people just come to talk and hear those stories—would be of great value?

BP: Oh, yeah. Definitely, I agree wholeheartedly on that. I’ve experienced some of this visiting dioceses and parishes who have structured special evenings of prayer and story-telling for just this purpose.

CD: You mention the historic events of the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act but also how there is a sense in which African Americans feel that they have not really progressed in many ways. One example is Black household median income versus the United States median income. In 1967, Black household median income was $28,510, about $20,000 below the national median of $47,000. Today, the median Black household income is $41,361, but the median for all Americans is $63,000. So now the gap between the American average and the Black household is nearly $22,000. So that gap has gotten bigger. I think that’s one of the things you were getting at with some of your previous answers. If we don’t even know things like that, we’re not going to understand why there’s such pain and heartache and anger.

BP: Exactly. Unless you have experienced being out of a job for lengths of time or having someone kneeling on your neck, preventing you from breathing, you have no idea of the pain others suffer from day-to-day.

CD: How do Catholics show their support for the principle that each Black life matters without being compromised in their Gospel witness to other fundamental issues? Bishop Earl Boyea of Lansing has pointed out that some of the tenets of the official BLM organization are inimical to Catholic beliefs. How do we walk with those calling out real injustice without casting a shadow on our witness to other core truths about the human person and the Christian faith?

BP: All social movements have their slogans which drive the passions and emotions nurturing a sense of freedom and relief. The Black Power Movement of the 1960s was one such. The Solidarity Movement with Poland’s resistance to Communist oppression is another. The Zealot movement during Jesus’s time was another. A couple of the apostles seem to have been at least Zealot sympathizers. Jesus knew of their platform, especially that some of its adherents were bent on violence to get rid of the Roman occupation. Social movements operate under a degree of hyperbole for the sake of getting their message across and tend to harbor extremes in thought and ideology. Social movements harbor their own inner-conflict and a certain degree of chaos. They tend to suffer under mixed reviews of the public.

For sake of finding the kernel of truth involved with the Black Lives Movement, perhaps it is better to speak of a movement for Black lives. Every intelligent person can empathize with what the kernel of truth of BLM is albeit its lack of structure and philosophy. It is the tag-along issues people bring that pose questions as to what extent we can acknowledge the BLM movement as conscientious Christians and as Catholics in particular. BLM, of course is not a religious organization. It is thoroughly socially ecumenical and open to a plethora of ideas. We are bound to run up against one or the other issue that cannot be reconciled with Catholic faith and action.

CD: Pope Francis has repeatedly called Catholics to remember that mercy is a name for God. As the roiling unrest has become a boil, we have seen people fired and “cancelled” for failures real and perceived. While we can understand the real anger animating those responding to George Floyd’s murder, is this an area where Catholics might be able to be a counter-witness? In other words, can we be instruments of healing and reconciliation rather than instruments of iconoclasm and revolution? And how do we avoid the danger on the other side of doing nothing or not doing enough? In other words, how do we avoid letting our concerns be coopted or become a barrier to doing anything?

BP: Healing and reconciliation are the principal social instruments of Christians. This same question was at issue between Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. The former advocated fierce resistance if not hinting at violence as a means to bring about change. MLK advocated, preached and taught non-violence. People impassioned by the social causes of the day have to choose which method they will use. Righteous anger can push one to either side—violent change or the Christian way of love of neighbor. Love the enemy enough and they have to change or go crazy. Not doing anything for the sake of the kingdom is not an option, for racism and Christian faith are mutually exclusive. Racism is a form of atheism, a denial of God.

CD: On this last theme of firings and cancel culture, I have thought in recent weeks of the late Cardinal George’s line that in American culture “everything is permitted but nothing is forgiven” whereas Christianity, “by contrast, says that many things cannot be done but that in the end everything can be forgiven.” Do we as Catholics have a special call to help people tease out the difference between justice and vengeance? Will this involve Catholics going against the grain of the typical political categories—both right and left?

BP: Justice is often misconstrued as vengeance. We are bent toward requiring that people suffer for what they put us through; we want retribution—but this leaves out the forgiveness of Jesus from the cross. Somehow, in God’s design of things, Black suffering, anybody’s suffering is a conduit for redemption. And seeing that some folks bear a heavier cross than others, from the Christian standpoint, they are indeed privileged to know the Christ through the instrument of his cross. There is no other Christ of history. God will, to our amazement, forgive it all in the end. Our handicap is that we have made a list of the unforgiveable ones and have attempted to deliver it to God’s doorstep!