How can lost authority be restored? We did not need the recent poll on belief in the True Presence to indicate that the authority of the Church is in crisis within the Church—to say nothing of her authority outside the Church. The crisis has been evident for some time and is deep enough that it is not clear what authority within the Church is. For instance, a colleague of mine was considering sending his daughter to religious education. He was reluctant to do so because he was concerned CCD was “indoctrination.” A fellow parishioner recently scoffed at the idea that the Pope cannot change the rules about the all-male priesthood: “They made the rules up so of course they can change them.” Some Catholics seems keen to rid the Church of Pope Francis, another group seems to think Pope Francis has his own unique magisterium. Many Catholics appear to choose which ecclesial authorities to follow. Once you are doing the choosing, you have exited the realm of authority. If you are looking to your own standard rather than a universal or even ecclesial one, you are not dealing with authority. We see this in way cafeteria Catholicism functions on both the Catholic right and left.

I want to explore what authority is and aspects of the crisis of authority is in the Church. To do this, I look to Hannah Arendt’s essay “What is Authority?” published in her Between the Past and Future. Arendt provides some resources for understanding what authority is by showing its eccentric structure and its suffusing nature. In other words, authority-based communities require a source external to the community, and they require a sense that authority, through hierarchical, suffuses the whole community. In this, I will argue that the crises of authority within the Church—while having many causes—can be partially traced to the continuing theological error or exaggeration of the ecclesia docens et ecclesia discens distinction.

Authority needs to be revived as a collaborative project between the members of the Body of Christ. To restore authority in the Church will require living out the apostolic life of the tota ecclesia as re-envisioned in the Second Vatican Council. In this, I will push beyond Arendt’s account by arguing for the need for mission for an authority-based community. Since Christ sent the apostles, it has been in preaching the Word that authority has been restored. In this I will be advocating for a model of lay-collaborative leadership grounded in the Church as the totus ecclesia in which authority suffuses the whole body of the Church in its evangelical relation to the world.

Arendt on the Demise of Authority

If we are to determine how to restore authority, we will need to understand what authority is. Hannah Arendt, a philosopher of community, argues authority cannot be confused with either force or with persuasion. Persuasion is also not operative within authority. To persuade means to argue with an equal; it is of a different order than obedience, which is the right mode of response to authority. By the time an authority feels compelled to persuade or compel, authority has already been lost. I think here Arendt is too strong or at least fails to see that properly authority teaches. The whole community exists as a community of learners who as learners can teach. The key is that what they teach is not their own.

This means that a distinguishing characteristic of an authority-based society is that it is hierarchical and so neither tyrannical nor egalitarian. In the hierarchical model, I obey the other because the other has been endowed with authority and we both believe in this endowment. Authority is an alterity-dominated mode of communal life. Those in authority have authority due to a source that is superior to the community. In an authority-based society the leader is followed because both the leader and the follower believe in the endowing source which forms the community itself. Arendt writes that:

The source of authority . . . is always a force external and superior to its own power; it is always this source, this external force which transcends the political realm, from which the authorities derive their “authority,” that is, their legitimacy, and against which their power can be checked.

Authority-based societies are hierarchical because they are all eccentric. They do not find their source purely within but receive it from without. The community is not autonomous because it does not establish its law by itself; rather, it is heteronomous in that it receives its law from another. Each person is in relation to the source as other to the community. The persons with more authority are not essentially different from those with less authority. Rather, they are together in relation to the endowing source of authority. Thus, any authority they exercise is granted and limited by the endowing source.

Arendt sees a pyramid as a fitting image of this. The pyramid as other-dependent in toto because its authority is sourced from without. This eccentric source structures the hierarchy, “The seat of power is located at the top, from which authority and power is filtered down to the base in such a way that each successive layer possesses some authority, but less than the one above it.” Every member has authority as a member of a whole; because, no figure depends on themselves for their authority. Due to shared authority, “all layers from top to bottom are not only firmly integrated into the whole but are interrelated like converging rays whose common focal point is the top of the pyramid as well as the transcending source of authority above it.” At each layer of the community, authority is granted and limited. All exercise authority together in the shared task of living according to the eccentric source.

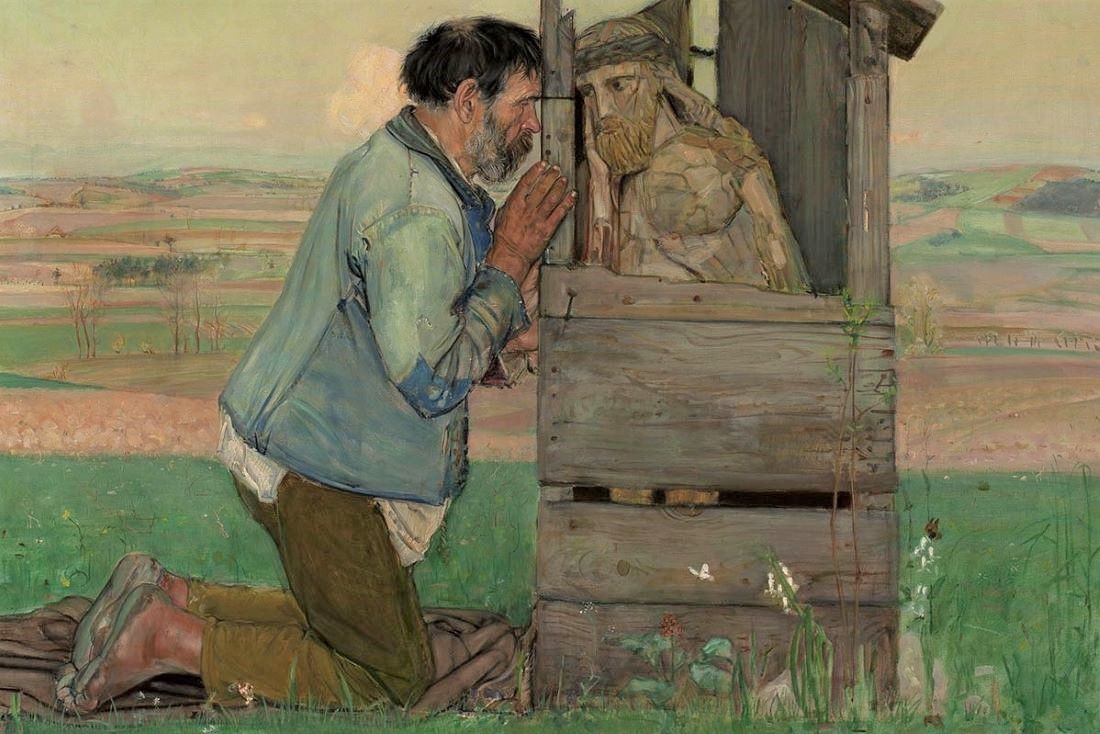

Arendt views Rome as the model of authority par excellence. For Arendt, the Romans saw the founding of the city as the singular event in history. This founding event is the source of the life and labor of the community. What is required then is the shared religion of the people back to this founding event: “Religare: to be tied back, obligated, to the enormous, almost superhuman and hence always legendary effort to lay the foundations, to build the cornerstone, to found for eternity.” The received task of all members of the city is to carry on this labor, the labor of the living city. Authority within the city is bound by this great founding and so only ever builds on it. Rome must hand down the founding story through tradition so that the community lives across time. In so doing it augments the foundation as a form of organic continuity. The test for the community is always: to what extent is an augmentation truly grounded in the foundation.

For Arendt, this idea of authority profoundly marked the Roman Catholic Church. Augustine made this possible by articulating a philosophy of memory for his philosophy of the person and of community. He thus forged a way of thinking about Christianity as a civitas peregrinus bound by memory to its Founder. Augustine converts the Roman ideals of authority, tradition, and religion into Christianity. In The City of God, he articulates the great event of the founding of the civitas dei in the life and death of Jesus. Christ is now the founder of the city, granting the task of authority to the life of the city through time. The endowment of that authority is to testify to the founding and so to limit one’s authority according to the testament of that founding. “The Apostles could become the ‘founding fathers’ of the Church, from whom she would derive her own authority as long as she handed down their testimony of tradition from generation to generation.”

But this authority cannot have only been handed to the Apostles and their successors. It filters down throughout the whole community of the Church through baptism. The entire life of the church is living out the Founding—augmented by preaching—while carrying forward the tradition through time. The authority of the Church is the endowment of the eccentric Founder who gives to us the task of being the City together. As Rowan Williams writes: we cannot forget “the Church’s character as a community that has been convoked or convened by an act independent of itself; so that we are all, in the Church, living ‘in the wake’ of something prior to all our thoughts and initiatives.” Christ is the head of the Church which is the totus Christus. The eccentric source is the wholeness of the community forming the whole Body of Christ.

These three elements—religion, authority, and tradition—are not the domain only of the hierarchy as a distinct part of the authority. It is precisely that the hierarchy cannot be a distinct part. Rather, the hierarchy is the whole lived out in different ways with gradations of authority. Further, the authority of any aspect of that hierarchy is due to the authority of the Founder. One carries on the tradition by being bound the source of authority. Once authority has been lost, it cannot be regained “Authority as we once knew it . . . has nowhere been re-established.” Once the power of authority has been lost, the community based on this authority ceases to be. If I no longer believe in the authority of the community, then no one within the community can possibly command that I believe. The only person who would obey is the one who had not ceased to believe the authority. In contrast, one who has lost a responsiveness to authority cannot be commanded to obey subsequent to this. They can only be forced or persuaded, in which case authority is moot.

Authority Lost

Authority, in its practice within the Church, is real because the whole Church has authority endowed by Christ through the Holy Spirit. Authority is enacted differently in each member, but the authoritative teaching of the tota ecclesia is the heart of this authority because the tota ecclesia is totus Christus. In each member, that authority is bound back to the Founder to whom we relate through tradition as an activity. Christ is the Founder of the ecclesial civitas whose task it is to speak with authority of the Founder in order to draw others to the ecclesial body.

One may be tempted to situate the crisis of authority within the Church with rising trends of theological liberalism. But this is to miss the force of Arendt’s challenge. The crisis of authority in the Church did not begin when people stopped obeying. It began when people thought there was one group in the Church who did the commanding and another that did the obeying. When authority is isolated within the group, it no longer suffuses the whole nor does present itself as sourced from without.

One source, then, of the crises of authority is the early-modern idea of the ecclesia docens et ecclesia discens, the Church-teaching and the Church-taught. This idea is first articulated in the writings of Thomas Stapleton, a theologian from the 16th Century. It became a dominant mode of thinking of the Church. As the Dictionary of Dogmatic Theology put it in 1951:

The Church is a society of unequals, in which by divine right some are superiors (the Pope and the Bishops) and have the authority of teaching, while the others are subjects (all the other faithful) and have the obligation of accepting the teaching of Faith and Morals imparted by the legitimate pastors.

My contention is not that the bishops and the pope do not have an essential role in carrying forward tradition through their exercise of authority, particularly as guardians of the deposit of faith. Rather, the essentialist divide between these two parts of the Church is what destroys authority. It treats one group as having authority—the group that does the teaching—and the other group as the group that “simply accepts what the hierarchy tells them”—they get taught without teaching. This is to corrupt authority by isolating it from the whole. The peak of the pyramid of authority was sundered from the base and somehow floats above the rest. From the floating heights, commands are issued. In the lived experience of people, they are issued from the top without much reference to the eccentric source.

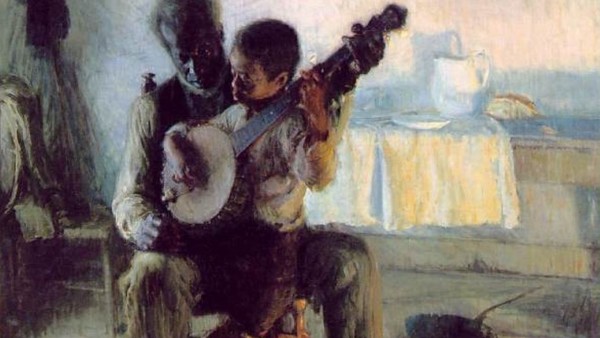

What Vatican II re-established is that the ecclesia docens is the tota ecclesia and the ecclesia discens is also the ecclesia tota. There can be no part of the Church that is not both teaching and being taught simultaneously. There is no Christian who is not both pupil and teacher in the schola Christi. Authority suffuses the whole even if its exercise and force may be less active among some than others. As Apostolicam Actuositatem teaches, “the Christian vocation is… a vocation to be the apostolate as well. In the organism of a living body, no member is purely passive: sharing in the life of the body each member also share in its activity.” In contrast, the language of “Church-teaching/Church-taught” treats a group of people (the pope and the bishops) as not being taught, and a group of people (the laity generally) as not teaching. Though members of the hierarchy rise through the ranks of the taught to become the teacher, we still have an account of teachers who are no longer learning in contrast to learners who never teach.

Thus, the source of authority gets harder to track down. If they are no longer taught, are they the authority itself? Do they determine what is to be believed? And if so, on what grounds? For Augustine, a bishop must be both teacher (doctor) and teachable (docilis). This is because for Augustine, speaking to his congregation about the bishops, “you are the Lord’s sheep, we are his sheep along with you, because we are Christians.” This is not to say Augustine obliterates the difference for “The Lord entrusted his sheep to us [the bishops]” but the bishops must never forget “We are fed and we feed.” To be a bishop is always more fundamentally to be one who is being taught. The authority a bishop has flows from his being taught and so able to teach. Though the bishop has a special role when it comes to teaching, it is a difference of degree as an expression of the life of the whole.

The language of two ecclesiae introduces a division in the body of the Church and thereby reduces one part of the Church to the theological category of the world. Christ did not send a part of the Church to teach another part of the Church. Rather, he teaches the whole Church so that the whole Church can teach the world. For Augustine, the Church is the school of Christ in which we learn what the good life is and those “who learn this are Christians, the one who teaches it Christ.” If there is a division within the Church between teaching and taught, it is the division between the Christ as head and the body. “It is Christ who is doing the teaching; he has his chair in heaven . . . His school is on earth, and his school is his own body.” We the members of the body are all teaching assistants, with varying degrees of seniority.

If there is a difference between Church-teaching and Church-taught in this world, it is because every human is a potential Christian and so the whole Church is to teach the world as ecclesia in potentia. As Christians in potential, the world is the ecclesia discens. Once we introduce a division of Church-teaching and Church-taught within the Church, we have made one part of the Church the Church and the other part the world. One hears this in common discourse when people who are Catholic talk about “the Church” as though it was a group of other people.

In this, the Second Vatican Council is an attempt at the restoration of authority. The Council Fathers reminded the whole Church that our mission is to “go make disciples of the whole world.” The laity have an apostolate because they too are the Church-teaching, the bishops are to listen because they too are the Church-taught. To say that the Church is the people of God is to remind us that all Christians are lay. Holy Orders is a sacramental distinction within the sacramental whole. Priests and bishops wear the stole over the alb because all the faithful wear the alb. The whole people receive the apostolate. This means the tota ecclesia is ecclesia docens in its relation to the world. The goal in missionary work is to make disciples, fellow learners, so that these fellow learners can become fellow teachers.

Authority Regained

I will leave it to better historians then I to track some of the aspects of the collapse of authority in the latter half of the 20th Century. However, the crisis of authority predates the collapse of authority. At a certain point, the members of the Church relegated to Church-taught—and so relegated to being the world—woke up and realized they were the world. When people talk about the Church and mean just the bishops or the pope, we have the groundwork for a collapse of authority.

What followed after the Council was an exacerbation of the problem as bishops and priests began to exercise authority detached from tradition. They began to act in an arbitrary manner according to their own personal preferences or contemporary mores. The group doing the teaching either seemed to be the group making things up. Meanwhile, the group who were supposed to obey suddenly realized that they had been secularized, transformed into the world. Further, many on the right and left acted as though the Church were in fact the ecclesia discens and the secular world the ecclesia docens. The theological groundwork of a mass exodus was made possible. It was hard to arrest because claims to authority was self-undermining. Bishops either made things up (why listen to them) or they hollered “you must obey,” which is not a very convincing message.

For Arendt, authority once lost has “nowhere been re-established.” For her, this presents the modern person with both grave challenges and a liberation for new possibilities. For those of us who remain committed to the Catholic Church it is both. We need to remain committed to “the religious trust in a sacred beginning” which we carry forward and to see in this moment new possibilities for grace in our world. We can do both because Christ the founder promised never to abandon his city. Arendt’s account cannot account for a God who will uphold the Church even in its diminished state. We may be suffering a collapse of authority, but the Authority has promised never to abandon us despite our self-induced crises. Arendt’s account primarily puts emphasis on the ways humans bind themselves to the authority of the origin; however, for the Catholic it is more important that Christ binds himself to the Church. True religion is ultimately not what we do; rather, it is God’s continuing covenantal bond with the Church. We may not be faithful, but God always is. The religion of God is God’s binding himself to us so that we can be bound to him. We are saved by Christ’s faith far more than being saved by our faith in Christ. For Arendt, “authority has vanished from the modern world” but for the Catholic it has not vanished because the Author of our Church remains.

That being said, a crisis of authority exists amongst both practicing Catholics and lapsed former Catholics, to say nothing of the “nones.” For Arendt, the collapse of authority is the source of freeing possibilities in our time because it allows us to “think without bannisters” as we are “confronted anew . . . by the elementary problems of human living-together.” Catholics too are re-presented with the problems of living together as a community. Catholics cannot pretend that all that many people feel bound by the teaching of the ecclesia tota.

To see how authority might be restored, I want to return to the idea of augmenting the founding. Catholic authority is only to be augmented by preaching, in short by persuasive teaching. For Arendt, persuasion is not a part of the authority-based community. But it is if that community is mission-oriented. In other words, Catholic authority is not only oriented ad intra but also ad extra. Within the community, persuasion matters for the practice of teaching. In this, since the whole church is ecclesia docens et discens, there is a responsibility to teach in compelling ways. The choir needs preaching too. However, authority in its ad extra orientation is sent. To be on mission is to be sent out from the community in order to bring others into the community. Since this orientation is always towards those who are potentially Christian, it means that the world is the ecclesia discens and the whole Church is sent to teach.

To truly believe authority requires we enact it by teaching. Since authority suffuses the ecclesial body, the task of teaching persuasively suffuses the ecclesial body. This is the heart of the Council’s repeated insistence on the apostolic nature of lay life. We too are sent. Part of the enormous strength of the Tridentine era was the sense that priests had a mission. Endowing the clergy with enough education, the Church sent them to preach. But the council did not activate the laity in the same way and so authority in practice increasingly drifted from the lay to the clerical. To restore authority today, requires not merely a renewal of obedience but a deepening of mission.

In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus’s ministry begins when he and the apostles enter Capernaum. Jesus taught in the Synagogue and “the people were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority [exousia] and not as the scribes.” The word here for authority is exousia. Rather than teaching about someone else or teaching through delegated authority, Christ teaches from his own being. When we preach as Church, we also preach exousia because the Church is the Body of Christ. The measure of our authority is the measure to which we preach out of the Christological reality of the Church. When I try to write from my authority, I do not speak from within Church. Jean-Louis Chrétien explains Augustine’s view teachers of the faith, particularly bishops: he “ceases to be a doctor of the faith when he ceases to let himself be instructed by universal tradition” and thus to speak “in the name of what he thinks” is to cease being a doctor of the faith. What is required is fidelity to the people of God and her shared teachings. It is this evangelical fidelity that grounds my obedience to the shared beliefs of the whole Church.

The Church authority is not something belonging to “the Church”—as in the hierarchy dwelling someplace else—but the Church as totus Christus. The Word was sent to redeem the world. He redeems the world by sending—with the Holy Spirit—the Church. As Joseph Ratzinger writes, the Church is a “new subject called into being by the Holy Spirit, which precisely for that reason throws open the impassable frontiers of human subjectivity, putting man in contact with the ground of reality itself. By its very nature, faith is believing communion with the whole Church.” While there are teaching offices in the Church, this is secondary to the Church as a corporate being preaching from itself inasmuch it preaches from Christ.

Considering this, we must unite the ecclesia docens et ecclesia discens. They are both always the same, all are teaching, and all are being taught. The parents teaching the Sign of the Cross teaches as does the CCD teacher. They teach because they are being taught. The same must be true of the whole hierarchy, which must be ever teaching and ever taught. This requires that the laity be treated as collaborators in mission. We are not delegated by the Bishops. Like the Bishops, we are delegated by Christ in Baptism and sent with the Holy Spirit in Confirmation. Vatican II proclaims: “Lay people’s right and duty to be apostles derives from their union with Christ their head . . . It is by the Lord himself that they are assigned to the apostolate.”

Conclusion: Collaborators in Mission

When Arendt sites authority, religion, and tradition as the three pillars of an authority-based community, she neglected mission as the fourth pillar. Perhaps she did so because one of her test cases—the Roman Catholic Church—has, too often, forgotten this as a part of the whole Church. The task for us—living in a Christ-forgetting world—is to enact mission and so restore authority. There are reasons to think that this is not likely to happen anytime soon. If the members of the Church—clerical, religious, and lay—are not keen on being discens, how are they to be docens? Importantly, Catholics, particularly the laity, are living out the mission of authority. A teaching mission grounded in fidelity to the authority of the Church as totus Christus already inspires missionary organizations like FOCUS, academic institutes like the Collegium Institute which brings the Catholic intellectual life to the University of Pennsylvania, and spiritual formators like Blessed is She, Ascension Press, and the Notre Dame McGrath Institute for Church Life.

The McGrath Institute’s Called and Co-Responsible Conference, can articulate an account of lay mission not only because of its foundation in the message of Christ and its forceful articulation in the Second Vatican Council but because many of the laity are fulfilling their co-responsibility. We not only need to articulate what should be the case regarding lay mission; we can also reflect on the seeds of evangelization being spread already. Most dynamic Catholic movements these days are lay founded or lay led. When they are not, they are enthusiastically supported by the laity, often prior to episcopal approval. We are already collaborators in mission, our task is to reflect on this and deepen and broaden this fidelity to the authority of Christ.

For Hannah Arendt, the challenge after the fall of authority is to be “confronted anew . . . by the elementary problems of human living-together.” In the crises of authority that wrack the Church in the Western world, we are confronted anew with the tasking of living together as Christians united in fidelity to our mission. The task is ever ancient and ever new because it is the task of the great commission. The apostles suffered from a crisis of authority both doubting and worshipping as we are today. Jesus’s response to us now is the same as it was to them then. From out of his authority, he sends us on mission to teach what we are learning. And he promises that he will be with us as our true Authority until he comes again:

When they saw him, they worshiped, but they doubted. Then Jesus approached and said to them, “All authority and on earth has been given to me. Therefore, go and make learners of all the nations. Baptizing them in the name of the Father, and the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all I have commanded you. And behold, I am with always, until the end of the age” (Mat. 28:17-20).