It is just one of Nietzsche’s many bon mots that if one stares at evil long enough it looks back. As is usual with Nietzsche there is an implied boast. We divide into the strong and the weak depending on whether we can or are willing to endure this look or looking back. Nietzsche leaves us in no doubt as to which camp he belongs in, even if with all the bravado about amor fati we sometimes get the impression in reading him that he is expecting as much our pity as our admiration. Still, the aphorism is powerful, and it is powerful not only because it is scintillating in its expression, but because it is experientially apt.

Over the centuries, as they looked at and into the world, victims as well as victimizers have experienced the force of that look or counter-look that announced that all hope should be abandoned and that our abused flesh empty itself of everything that makes it human and all will to be human. With regard to victims we have the searing accounts of the dehumanization in the concentration camps in the Shoah in which the prisoner loses her subjectivity, initiative, and dignity. Primo Levi and Eli Wiesel are but two of the writers who memorialize a form of existence whose living death moves towards the form of a zombie.

In roughly the same time period, in working in the factories in pre-World War II France, Simone Weil uses a bifocal lens to link together the suppliants pulverized by circumstance in Greek tragedy and the French factory workers she works alongside in solidarity despite her being bejeweled with academic achievements. These workers, beaten down by fatigue and numbed by repetition, are absolutely fungible. For Weil, abjection and destitution is now as in the time represented by Sophocles a historical universal of the devastation that human beings visit on each other until the last vestiges of a sense of outrage evaporates and the demand for justice come to be seen as a luxury in a world in which torpor and nescience are the inhuman conditions of survival.

For Primo Levi and Eli Wiesel, it is too much to ask that a human being not yield, not to erase a subject point of view and the ability to take stock. The yielding comes when the defeated experiences the looking back of the evil that emptied them of courage and crucified their loves, a grimace of nothing into which all promise vanishes and the only assurance to be relied on is that the suffering of tomorrow will be at least as bad as the suffering today.

***

It is harder to imagine the looking back that the victimizer endures and thus the recognition of damage he has done to himself through the damage he has done to others. The difference, and thus the difficulty, is that the victimizer is the perpetrator, the subject who apparently remains autonomous and thus is culpable. Still most victimizers were not victimizers at birth; they came to be who they are through contagion, an ideological construction riven with fear of some other, whether ethnic group, nation state, a group with a different ideological persuasion, or individuals who have been granted the insider status that they were unfairly denied.

In addition, the victimizer was often enough once a victim, an object of contempt, hatred, invisibility, or at the very least perceives himself to be such. For the victim to mutate to victimizer is to be given the power and opportunity to pay back a previous victimizing or to forestall one perceived to be in the works. Needless to say, the threshold for provocation to turn into a victimizer can be very low: tales of long past victimization may be sufficient for atrocities to be committed on groups or certain kinds of individuals.

Moreover, the perceived danger may not be imminent, but long in the future, or perhaps just a mere logical possibility. Victimizing may be direct or indirect, direct in that a person is willing to humiliate or torture or even kill individuals and groups of individuals, or indirect in that a community or nation-state can insist on the not-quite human status of a group at their borders or inside their borders thereby inviting persecution and the release of all the pent-up violence engendered in the divisions and imbalances in a society.

For the victim, the victimizer is the sign of the erasure of my humanity. For the victimizer things are more complicated. Whether sexual predator, serial killer, torturer, ideologue, or simply ideologically persuaded guilty bystander, there is often a split between one’s terrorizing and violating the dignity of others and what one does and is in the context in “real life,” in your family, community, and religious organizations. Splitting is the basic defense measure in and through which perpetrators repress guilt, but also keep at bay their encounter with the return look in which what looks back is vacancy itself. This is a look that crushes all hope of renovation and repentance, which locks one in to the horror of what one has done and allowed to be done.

***

There is a third and varied constituency for this look back, adventurous spirits who would truly know the horror of evil. They are the intellectually and morally adventurous types like Nietzsche; those who privilege curiosity and who would think it cowardly not to inquire and understand—maybe even taste—life’s forbidden fruits. If such examples abound in literary figuration, in Byron, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and dozens of tawdry imitators over the past two centuries, there are even more in real life, even without counting the effects of the modern rhetoric of experiment that may have artificially swollen its ranks.

Belonging here also are the moralistic cataloguers of our many perversities, who in the name of justice refuse to stop at the door of human atrocity and proceed to beseech, pray or be silent. Rather, in order to authentically memorialize the victims they feel obliged to stand in their place and provide the testimony that was deprived them throughout their many hours, days, weeks, and months of the peeling off of their humanity whose sweetish wish was oblivion. Virtue can make hell as vice can, and one does so by absolving the distance—sometimes almost infinitesimal—between one’s truly seeing what was done to the seeing of the victims and actually recapitulating the experience of the looking back that scoops out seeing, poisons the will, and stops the heart.

***

Nietzsche only recognizes the third of these constituencies and within that only the regiment of the curious rather than those so fervent for justice that in solidarity with victims they become undone. More narrow than at first sight he might appear to be, even here Nietzsche proves not to be entirely adequate. In his great texts of declamation and rhetorical self-construction he shows himself to be both something of an aesthete and a borrower: an aesthete because he fails to see that reality provides examples before it offers verbal incentives, a borrower because he was writing in the waning of the long nineteenth century which had provided numerous examples of a descent into hell and more than some examples of a look back that destroys.

The friend of Hegel and Schelling, the poet of “madness,” Friedrich Holderlin, provided an example of a surging chaos looking back in his famous dramatic verse poem on Empedocles, where in his desire for apotheosis dives the hero into the cauldron of Mount Aetna as if it through a form of alchemy it could redeem his sacrifice and verify his greatness. Schelling, once the friend of Hegel, now his enemy, provides a description of the magnetic pull of chaos in his famous Essay on Human Freedom (1809), while sanely recommending against yielding to it. To see into it is to be mastered by it and lost. Much to Nietzsche’s chagrin in his reflection on will and drive Schopenhauer offered similar “cowardly” advice, which the would-be Übermensch who would transvalue values mockingly rejects. And before Schelling, in the depth dives, of German thought into evil there is Jacob Boehme’s reflection on chaotic, meaningless, relentless drive that is part of the essential make-up of all reality. The chaos that insists on itself and resists sublimation invites a looking so deep that the subject becomes the chaos looked at. The issue is the disintegration of the self and the cutting off of any prospect that even the bare hope of goodness will survive.

And again before Boehme there is Paracelsus, or to give the famous Renaissance alchemist, who was one of the figures behind Goethe’s Faust, his true appellation, Theophastus von Hohenheim, to which “Bombastus” was usually added and with good reason. Paracelsus puts a focus on imagination as a power of shaping long before Coleridge speaks to imagination’s “esemplastic” power in Book 13 of the Biographia Literaria (1817). Yet, Paracelsus does so with a profound grasp of evil that surpasses what one finds in Coleridge and also the early Schelling on whom Coleridge’s views of imagination depend. Precisely as a creative power imagination not only can but must take on the shape of what it imagines. Crucially to imagine evil or the formless is to be impregnated by it. Paracelsus may have illegitimately feminized evil, but there is something that this Renaissance fraud, who is echoed and refigured in Goethe’s Faust, knows that enlightened moderns do not know.

***

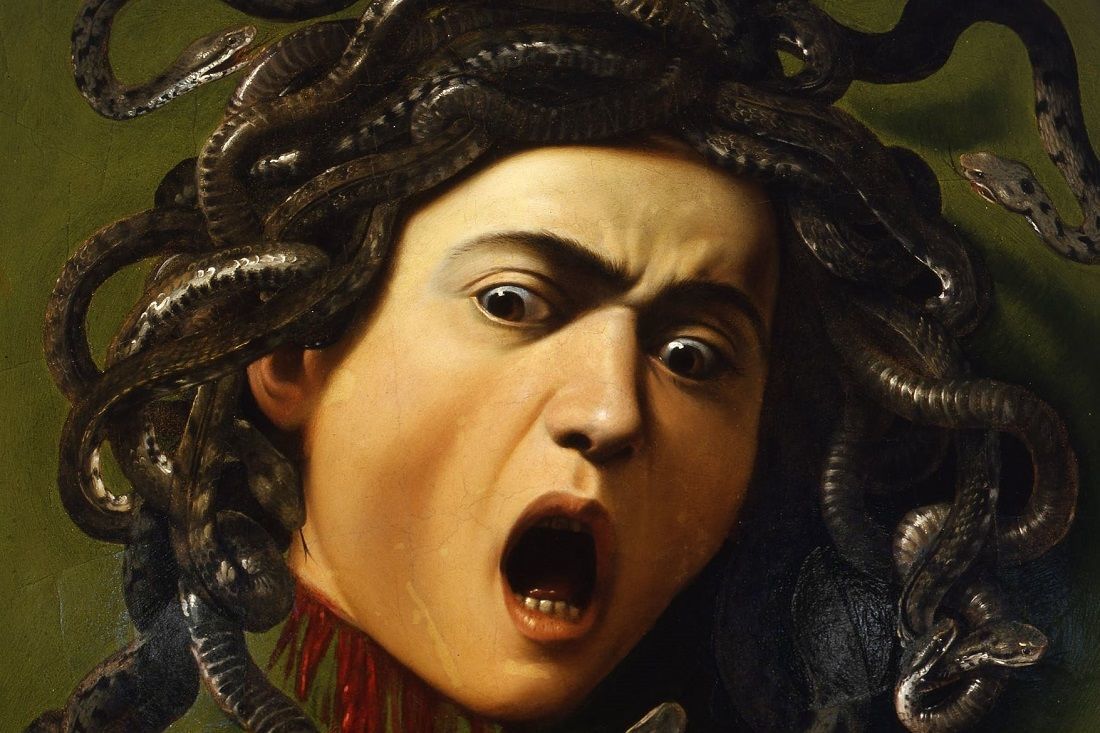

Needless to say, the archetype of the return look is the stare of Medusa. With her multiple heads and writhing limbs Medusa is the untamed formlessness, denied but ready to repay the insult. She is a killer, but she seeks human complicity in our death, a yes or half yes that makes it ambiguous as to whether she or the subjects who look are to blame for their ceasing. When her gaze meets our gaze, we petrify, we cease to be subjects who look; we are objects without becoming or change, without a future of satisfaction or renovation.

Medusa is the figure recalled in Nietzsche’s aphorism, the dare he entertains for himself and puts before us. He suggests with regard to the figure that is hidden in his hyperbole the possibility that a human being, albeit one that is divinized, might, indeed, survive the look. Schelling on behalf of the curious, but perhaps also all victims, victimizers, and the righteously self-sacrificial, says that only God could survive, only a divine look could short-circuit the look that looks back.

But is bottomlessness the last word which we only avoid by humility, moderation in the acceptance and doing of evil, and sheer luck? Is the return look the absolute look? We have suggested already that for a believer this is not the case. God’s look is infinitely more powerful and life-giving that all our looks, as it is more powerful than evil’s reverse look. If the Renaissance philosopher-mystic Nicholas of Cusa is right, God in Christ is the communication of the divine look that is grace. But this look of unsurpassable concern and love is experienced as a return look.

In the aptly named The Vision of God God is both objective and subjective genitive, what is seen—if only through a glass darkly—and what sees. Cusa opens his text with an image intended to provide orientation and to provoke wonder. He imagines monks, placed in semi-circle around an image of Christ—modeled on a painting of Veblen—in which, as they look at the icon, the icon seems to return their gaze whatever their place in the semi-circle. The gaze of the loving and vulnerable Christ as the icon of God is referenced to each as if they were all: it is seeing and knowing as infinitely solicitous, beneficent, and forgiving. It is love’s knowledge whose intention is to decongest the heart, cleanse the imagination, and give the self back to itself as agent who precisely as such can express gratitude. The gaze does not petrify, does not make one sheer past without memory. Rather, loosening, it gives a future. Not only that, it makes the self a tireless and joyous future that it was meant to be. If the return stare of Medusa is the universal limit of evil, the stage of its final and complete victory, the return gaze of Christ, the icon of the loving God, is its anti-type, the look back that we should be looking for in all our dark individual and communal nights in which the return look of evil appears to be our destiny.

This essay continues an earlier three-part installment by Cyril O’Regan on the monstrous in modernity.

Featured Image: Caravaggio, Medusa, 1597; Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD-Old-100.