As one of the great festivals of Christianity approaches, the malls are decked with holly, sales, and “Santa Baby.” Human beings are wired for festivity but could most of us even define what a festival truly is? And does our commercialized bastardization of Christmas still qualify as one?

When I picked up 20th century German Catholic philosopher Josef Pieper’s In Tune with the World: A Theory of Festivity, I realized this seemingly familiar idea of festival was more elusive than I expected. Did I not know what festivity was? Apparently not. The short treatise begins with a quote from St. John Chrysostom: “Ubi caritas gaudet, ibi est festivas” or “where love rejoices, there is festivity.” Like “love,” a word that we often use and yet may struggle to define, festivity is an idea we have trouble getting to the heart of.

In addition to Pieper, I would like to recruit a well-known guide for us in our search for the meaning of festivity: the “squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching covetous old sinner” turned grateful philanthropist, Ebenezer Scrooge. When the stage is set in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol there is no more unfestive soul than Scrooge. He is a friendless, greedy, cruel, and miserly bachelor who tortures his only employee and would not be mourned by one soul upon his death. When his jolly nephew, Fred, comes to wish him a Merry Christmas he responds with an ill-tempered “bah humbug!” In fact, in addition to refusing to participate in festivity, he cannot even comprehend it. He resides in an insular world (he is “solitary as an oyster”) in which no warmth or festivity is possible. Upon criticism of being “cross” on Christmas Eve he rails, “What else can I be . . . when I live in such a world of fools as this?”

Scrooge’s worldview prizes only utility. For him, the idea of taking off work for an entire day to celebrate Christmas is an absurdity. Like the utilitarians Pieper describes, Scrooge sees a Christmas Day rest from daily toil for his poor clerk, Bob Cratchit, as nothing less than a sabotage of work. A day off for festivity is merely theft to Scrooge. It is “picking a man’s pocket every twenty-fifth of December!” While Dickens does not call him an atheist, Scrooge’s every thought and act deny the idea of transcendent significance to life and his fellow creatures. The barbaric prisons and workhouses of Victorian England are to Scrooge useful institutions rather than assaults on human dignity. The poor debtors who would rather die than reside there “had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.” This soulless utilitarianism renders him incapable of understanding why his nephew (or anyone at all) has reason for wishing him a “Merry Christmas.” His accepted reality cannot coexist with festivity.

For festivity to exist, there must be joy. And yet joy is not the source of festivity, but flows from the affirmation that “everything that is, is good, and it is good to exist” (In Tune with the World, 26). An affirmation of the goodness of creation and gratitude to the Creator is necessary to achieve festivity, but the self-centered, bitter lens through which Scrooge views the world holds no possibility for joy. If joy is, as Pieper says, “the response of a lover receiving what he loves,” then when nothing and no one in the world are beloved, rejoicing is impossible. Scrooge’s “bah humbug!” is the only reasonable response to a Christmas greetings because he does not affirm anything in creation as truly good or meriting gratitude to the Creator. To flip around St. John Chrysostom’s claim, where there is no love, there can be no festivity.

The plot of A Christmas Carol takes Scrooge on a journey that shakes him out of his atheistic utilitarianism. To see creation as truly good he must first have an interaction with the supernatural. A visit from his late business partner Jacob Marley and an encounter with the three spirits of Christmas clarify his warped vision by revealing shadows from his past, images of his present, and possibilities for his future. The Ghost of Christmas Past carries him into his own memories. He visits his childhood, adolescence, early adulthood, and friends who lived with a spirit of generous gratitude. What most deeply affects him are the painful memories of his own failures. In order to take the first step toward affirming the goodness of existence, Scrooge must acknowledge all his self-inflicted losses as true losses. In other words, he must affirm the goodness of what he lacks: his lack of relationship with any relatives or friends and his broken engagement to the woman he loved who was displaced in his affections with the acquisition of wealth. Scrooge’s grief over these sorrows affirms through negation the goodness of the love and family life he will never have and this lays the groundwork for all that follows.

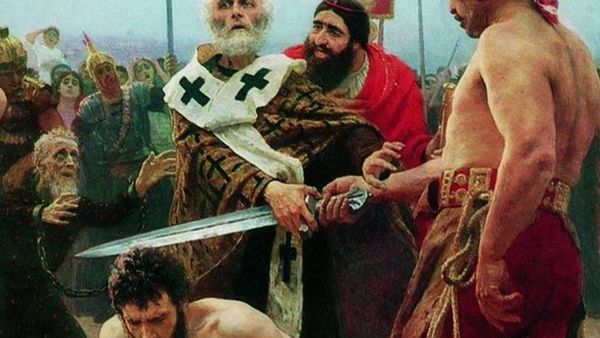

Scrooge is then visited by the second spirit of this trio, the Ghost of Christmas Present who gives him a clearer picture of the goodness of creation. He shows Scrooge scenes of gratitude where people are celebrating the festival of Christmas. The exuberant and festive nature of this spirit transcends mere cheerfulness (which Pieper claims is not enough to merit festivity) and he boisterously brings feasting and joy with him everywhere he goes. He presents Scrooge’s clerk’s family’s celebration of Christmas as a model of festivity. In the Cratchit’s home where the inhabitants view each other as beloved gifts of the Creator, there is joy: “Ubi caritas gaudet, ibi est festivas.” While this poor family has a very small budget for making merry, a feast is prepared with the lavish “germ of excess” that Pieper notes accompanies true festivity. The Ghost of Christmas Present explains to Scrooge that he is the youngest of many brothers that go back almost 2,000 years in a continuous line—an image Pieper would appreciate as he emphasizes the past, present, and future nature of true festival.

Finally, the eerie, cloaked Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come arrives to silently point out scenes that may unfold upon Scrooge’s inevitable death. In these visions no one mourns Scrooge. The only emotive response to his lonely passing is glee from those he oppressed and his few possessions are carried off to a pawn shop while he grows cold in his bed. These horrors startle Scrooge into supplication for a transformed life and future, not merely because he fears death but because the goodness of existence has become strikingly clear. Only with this understanding of existence as a gift to be received with joy is he fully prepared to celebrate the festival of Christmas. As Pieper says, “Can it be that this goodness [that of existence] is never revealed to us so brightly and powerfully as by the sudden shock of loss and death?” (Ibid., 29). This is the shock that Scrooge needs in order to have his vision restored to see that gratitude to his Creator is the right and just response to the goodness of creation, gratitude that extends into his interactions with his fellow creatures.

By introducing him to the supernatural, the three spirits prepare Scrooge for true festivity. According to Pieper, an encounter with the divine is always a necessary element to a true festival. Regardless of religion or cultural traditions a true festival is founded not by humans but by divinity. It must be rooted in an event in which the supernatural touches the material—it cannot be observed merely in praise of a nebulous idea or a mere memorial. Something real must happen. For instance, Easter, Pieper claims, would not be a true festival if it only celebrates the idea of re-birth or immortality. It must celebrate the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. Furthermore the festival must reach beyond a historical moment in the past to touch us in the present and it must point to a hope for the future. For a festival to be a true festival it must, in some sense, be always happening, a “mysterious contemporizing of this event” (Ibid., 49). Easter is not merely the memorial of a historical moment but a celebration of the continuous reality of the Resurrection. With this understanding, it makes sense when Scrooge says, “I will honor Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, Present and the Future.” Because a true festival is always occurring, it must, in some sense, be kept all the year.

Scrooge’s observation of Christmas does not take place merely in his “heart” as a personal emotive response. He participates in the true culmination of festivity: public worship. Dickens tells us that on Christmas morning, upon waking up to a new day and a new understanding of reality, Scrooge heads to church! Pieper argues,“The only fitting way to respond to such gift [the goodness of existence] is: by praise of God in ritual worship. In short, it is the withholding of public worship that makes festivity wither at the root.” (Ibid., 71). Scrooge’s transformation is helpful in understanding the affirmation of the goodness of existence as the foundation of festivity, but also as a model for the proper response for celebrants of true festival. In the Mass the goodness of existence is affirmed and grateful praise is given to God, the Creator, in ritual worship. Once this public worship, the point upon which festivity spins, is removed as the primary celebration, a festival degenerates into artifice. When ritual praise for the Incarnation is no longer the central point of the great festival of Christmas, the result is our culture’s observance of Christmas: a consumerist sham that falls short of true festival.

We are designed to crave festivity and when we lose the practice of observing true festivals, we replace them with sham festivals. Pieper explains, “The place in life which should naturally be occupied by real festivity cannot remain empty” (Ibid., 69). But how do we discern what is a true festival and what is a sham? The foundation of an artificial festival has no true anchor in the transcendent. True festivals, on the other hand are founded by divinity, reach their culmination in public worship, encounter the supernatural, are based in the affirmation of the goodness of creation, are rooted in the past yet touch the present and point toward the future, and result in art and joy.

The way our culture celebrates festivals that were once observed with true festivity reveals how our current celebrations fail. And if a culture’s festivals are self-portraits as Pieper claims, our sham festival of Christmas reveals nothing good about us. “The fundamental vapidness of these artificial festivals is clearly exposed when we try to find out what they are actually celebrating,” says Pieper (Ibid., 70). What a true festival celebrates is clear. Christmas, for instance, celebrates the Incarnation of our Lord. This celebration may result in families spending special time together and feasting. Warm feelings may accompany it. But when asked, “what is Christmas all about?” our answer should not be merely the idea of warm feelings, a generous spirit, or family togetherness. A true festival cannot be based on such fuzzy concepts. Not to mention how absurd the idea of a holiday about family togetherness would be to any culture but our own disconnected and isolated society. If the Incarnation is not the point of celebration then there is no point, no true festival.

What does our modern, secularized, consumerist Christmas celebrate if it is no longer based in the reality of the Incarnation? Our Christmas becomes a confused and muddled attempt at festivity that, while touching our sentimentality, reveals nothing substantial below the surface. Perhaps this is why there are so many cheap Hallmark movies about looking for the spirit of Christmas. They get one thing correct: we have lost it! But the key to finding it is not a long lost relative, engagement ring, or even a family meal as the snow falls softly outside. As Pieper notes, “If the Incarnation of God is no longer understood as an event that directly concerns the present lives of men, it becomes impossible, even absurd, to celebrate Christmas festively” (Ibid., 24).

But is this such a problem? After all, encouraging family time, sharing a pecan pie, having feeling of goodwill toward our fellow man--are these bad things? None of these things are evil, or even negative and any could result from the joy that flows from festivity. But using them as the reason for festivity while ignoring any substantial basis of true festival is dishonest. Pieper argues, “Worse than the silencing and stifling of festivity and the arts is sham practicing of them . . . The sham is inherent in the fact that the affirmation and assent compatible only with true reality is falsified into a smug yea-saying, whose basic element is a desire to fend off reality” (Ibid., 58-59).

If distancing the observance of Christmas from public worship was the first step in the degeneration of this festival, communal festive traditions quickly followed being replaced by consumerism. Pieper says, “Most of the great Christian festivals have been taken over so completely by commercialism that their degeneracy is almost total” (Ibid., 84). The critique of the commericialization of Christmas (that it “doesn’t come from a store,” as Dr. Seuss phrased it) is not a new or revolutionary one, but it is apt. Our obscene consumerism in the guise of celebration is not the same vice crotchety Scrooge displayed. Scrooge, although rich as Croesus, had the means to make merry and yet, until his transformation, he eats gruel in a cold house, skimping even on enough candles to light his home. He perfectly illustrates a utilitarian world “marked by scarcity and impoverishment even when there is the greatest abundance of material goods” as Pieper describes (Ibid., 19). Our observance may not be as bleak as miserly Scrooge’s lack of celebration but our failure to comprehend festivity comes from a similar source: a utilitarian worldview with an obsession with wealth. What made Bob Cratchit worthwhile in the eyes of his employer? His work as a clerk. We laud a different kind of “work”: that of consumption. We are made useful in our economy by our consumerism. So how do we observe Christmas? We buy things in excess. Our celebration of the great festival of Christmas becomes a sham in service of “the economy.”

Pieper warns that an artificial holiday “borders so dangerously on counterfestivity that it can abruptly be reversed into ‘antifestival.’” (Ibid., 79) While I am not sure our modern Christmas celebrations have become fully antifestive, we can see false festivals emerging such as Black Friday or Amazon’s Prime Day that are truly the opposite of festivity. Instead of public worship born from gratitude to our Creator for the goodness of existence, we observe these “holidays” born out of our greed and dissatisfaction attempting to fill up our lives with more, more, more. We are committed to such antifestivals despite the fact that they lack even the trappings of festivity—none of the music, art, or visible celebration that accompany a true festival. It is difficult to understand how such “celebration” of hitting the mall (hours after Thanksgiving dinner), while certainly not festive, is even remotely pleasurable. These antifestivals reveal a profound lack of gratitude with no orientation to the transcendent. Pieper says, “there can be no deadlier, more ruthless destruction of festivity than refusal of ritual praise” (Ibid., 32). Can anything be less like grateful praise than fighting Black Friday crowds for sales on items to bring home to our already cluttered houses?

So are we doomed to antifestival? Not necessarily. Pieper prophesies that “Two extreme historical potentialities have equal chances: the latent everlasting festival may be made manifest, or the ‘antifestival’ may develop in its most radical form” (Ibid., 87). While “celebrations” like Black Friday seem to fit the bill for the most radical form of antifestival, it is not impossible to rediscover the reality of the great Christian festivals.

How can we genuinely celebrate the great festival of Christmas? We can participate in the ultimate form of grateful praise—the Holy Mass—the content of which Pieper says, “is nothing other than the salvation of the world and of life as a whole” (Ibid., 38). Our joy, a result of heaven touching earth on the altar, can flow into our feasting, our families, our gift-giving, our holiday traditions. We can allow the reality of the Incarnation to affect our days all the year. Pieper claims that “Man craves by nature to enter the ‘other’ world, but he can attain it only if true festivity truly comes to pass” (Ibid., 59). It is time to enter into the miracle of the Incarnation, where the Christ Child comes to enchant the world with his blessed steps. If we can embrace this reality of heaven touching earth as the basis of our festivity, then the holy, joyful, and even raucous celebration of Christmas can burst forth like the newly redeemed Ebenezer Scrooge into the streets of London, rejoicing at every face encountered as an image of the God who made all things and made them truly good.