Robert Macfarlane, a Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge University, has reignited the discussion on the connection between nature and the imagination. In Landmarks, his most recent book on the unique regional words used to describe English landscape, Macfarlane comments that “Our children’s vanishing encounters with nature represent a loss of imagination as well as a loss of primary experience.”[1] If Macfarlane articulates a concern for the disconnection between the decreasing number of experiences in nature and the imagination’s vigor in secular culture, is it such a great leap to question the connection between the imagination and the spiritual life? This very question was pondered by Father Conrad Pepler, O.P., a member of the English Dominican province, who addressed this topic some 60 years ago:

There is a need of an imaginative response to life, a training of the imagination, not merely in a few cases of poetic talent, but as a common function in every member of society. Incalculable harm can be done to men generally by the perversion or deadening of this faculty. When society becomes entirely secular and mechanized, men’s common experience and imaginative furniture becomes secular. Divorced from nature and from a common religious experience, their minds are furnished with a stream of secular images and symbols. As the sensations flow on, the spiritual, creative forces of intellect and will are dulled. Men thus become more easily carried along in the stream of a mechanized external life.[2]

In developing Pepler’s observation that experiences in nature, the formation of the imagination and the spiritual life ought to be congruent, we will consider two major questions: How is the imagination formed and why is the imagination essential for the New Evangelization?

How is the Imagination Formed?

In addressing the first question, how is the imagination formed, let us adopt two phrases to frame the process: Look Out and Look In. The first phrase, Look Out, suggests that a person encounters stimuli through the physical senses: sounds, textures, tastes, colors, scents. These stimuli become the building blocks for the imagination; hence, for children, the quality and quantity of experiences is vital in establishing a foundation in learning. In Look Out, a person is directed outwards, in conversing with another, examining a seashell, observing the clear night sky that is suddenly illumined by shooting star, by identifying the paramecia in a drop of pond water. Look Out necessitates the ability to wonder, to question, to search, to experiment.

Look In, the second phrase, may be subdivided into the act of the imagination and a period of reflection. Many of us equate an artistic flair or a brilliant idea as evidence of an imagination, as may be illustrated in a scene in Charles Schulz’s Peanuts comic strip. Sally receives a “C” on her coat hanger sculpture, and questions, “How could anyone get a ‘C’ in coat-hanger sculpture?” This initial rhetorical question is followed by a flurry of questions about judging and grading creativity.[3] It will be well to note that the imagination is not solely a vehicle for creativity or that the people who lack artistic talents have a weak or ill-formed imagination. St. Thomas Aquinas offers a broader view on the imagination’s role and its interaction with the stimuli and the intellect. The stimuli received from the physical senses are stored in the imagination, and the imagination rearranges the stored stimuli. Perhaps this example may help: you see and touch gold objects, whether jewelry, gilded china or artifacts in a museum. You also know that gold objects have different sizes, shades, textures. All this stimuli is stored in your imagination and is ready to use. You may live in a mountainous area, but if not, you certainly have seen photos of mountains, such as the Rockies, the Alps, the Smokies, and know that some mountains are rocky and snow-covered while others are fertile and tree-covered. Now, if I utter the phrase “gold mountain,” you can visualize this in your imagination even though a gold mountain does not exist (ST I, 78, iv). The integration of “gold” and “mountains” into a “gold mountain” is the imagination at work. How each person imagines the gold mountain will be dependent upon the images stored in the imagination.

The stimuli and images that enter the imagination are significant, and of critical importance are the experiences in the natural world which are the primary influence in forming the imagination. Reflect upon the number of natural images are contained in the Psalms, the parables, the Letter to the Hebrews, the Book of Revelation: lofty cedars, leafy oaks, lions prowling, fresh sprouting leaves, the lilies of the fields, mountains that leap like rams and rivers that clap their hands. These primary natural images become the foundation for symbols, metaphors, similes and allegories that are used to describe the sacramental and spiritual life, as found in mystical writers, such as St. John of the Cross, St. Hildegard von Bingen, or Caryll Houselander. Pepler, whose childhood and adolescence was spent in rural Sussex, was convinced that formative experiences exploring woods, beaches and meadows were essential to the imagination, but more importantly because they are a bridge to the sacramental life. Pepler offered the following conclusion:

In theory it might seem to be a matter of indifference whether the imagination were formed by natural things like seeds sown and growing into plants—lilies—and sparrows flying or falling. Closer investigation, however, shows that imagination cannot be altogether rationalized and treated as a meter instrument of human thought and willing. It is the bridge to the whole universe, with the rhythm of the heavenly bodies, the movements of creatures of every description coming over that bridge into man and so reaching up to God in this new world of intellect. It is this natural world which provides the sacraments and the sacraments gain entry into man’s spirit through this inner faculty where poetry is created and understood.[4]

The imagination assists in forming an “interior landscape” of the spiritual life which helps us navigate through the dark valleys to the restorative green pastures. For Catholics, the imagination is not an escape to a fantasy world. The imagination aids us in seeing the real world by integrating the natural world and the supernatural world, the visible and invisible.

Seeing the real world as God does requires a time of reflection, and this period of contemplation composes the second part of Look In. St. Thomas defines contemplation as “the simple act of gazing on the truth” (ST II-II, 180, iii, ad 1). Natural contemplation was part of the normal day of ordinary people as recounted by historian Roger Ekrich in At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past: “On myriad evenings, growing numbers of men and women devoted an hour or more to solitude and mental reflection, resulting ultimately in an enhanced self-awareness. Individuals found evenings particularly well suited to contemplation, as religious sages had for centuries.”[5] In the tumult of the current digital tsunami, suggesting a period of silence and technological disconnection seems archaic, but as the journalist and social commentator Andrew Sullivan concludes in a revelatory article about his own information addiction, “This new epidemic of distraction is our civilization’s specific weakness. And its threat is not so much to our minds, even as they shape-shift under the pressure. The threat is to our souls. At this rate, if the noise does not relent, we might even forget we have any.”[6]

Look Out and Look In proposes that in the formation of the imagination these two elements are needed: primary experiences in the natural world and a period of contemplation to allow the imagination and the intellect to interact. By understanding how the imagination works, we can now advance to the second question: Why is the imagination essential for the New Evangelization?

Why Is the Imagination Essential for the New Evangelization?

Forming the imagination is a pre-evangelization task; a secular imagination may struggle to understand the symbolic words and images of the sacramental and liturgical life which are based on the natural world. Altering or disregarding natural symbols excludes archetypes that have become embedded in cultural myths or religious narrative, such as light and darkness, the fertility of land and the rhythm of the seasons. Man’s attempt to change natural symbolism to adapt to the needs of artificial society, such as the fabrication of winter holidays to replace Christmas, are self-defeating. These attempts often result in the manufacturing of kitsch, which reduces a symbol into cuteness. The English scholar Roger Scruton identifies kitsch as a disease of faith and observes that “people prefer the sensuous trappings of belief to the thing truly believed in.” [7] The reduction of symbolism, whether by eliminating religious holy days or by kitschification, from ordinary life and the public square, weakens the bond between natural and supernatural lives. The secular culture is not completely barren of symbols, e.g. Earth Day, recycling, but the symbols lack the vitality to point us towards the transcendent or to signify the Other. Men and women are searching, at times grasping at pseudo-spiritualties, to find the connection, the bridge between the natural and supernatural. An imagination that is deprived of natural world experiences, that is stocked with secular images, will have to be fertilized and tilled before receiving the seeds of the Gospel.

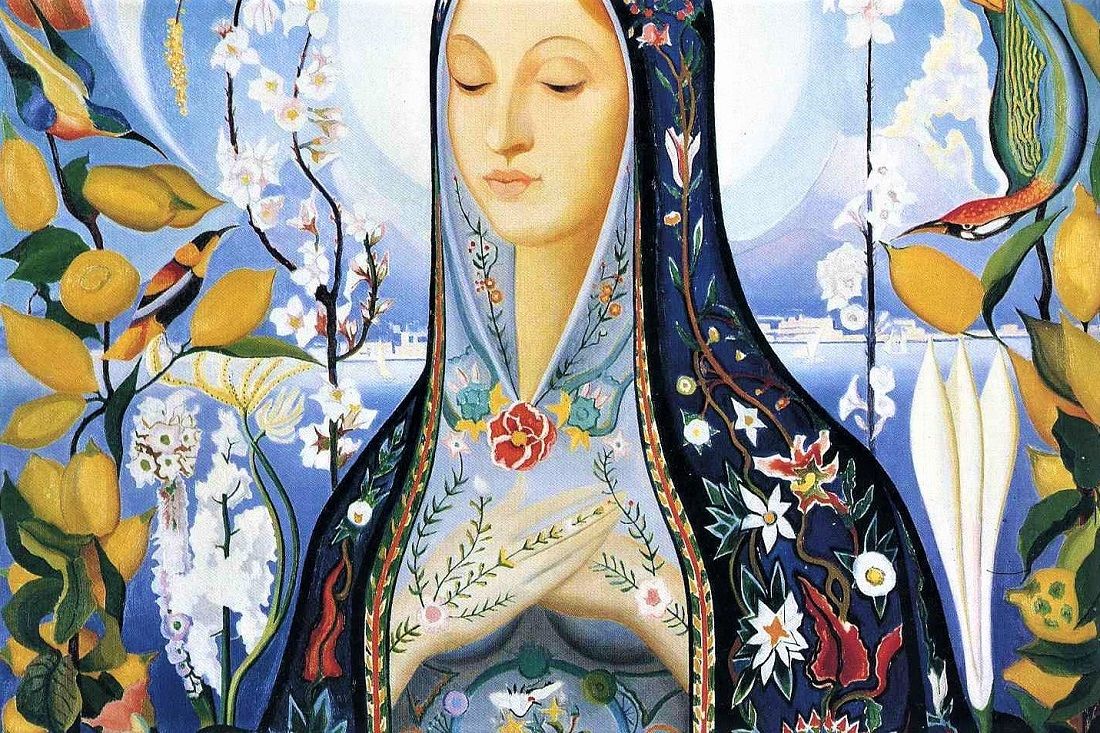

Drawing attention to symbolism may be able to ignite and captivate the wonder and desire instilled within each person. Families, Catholic schools and parishes can promote a renewed understanding of the connection between nature, symbols and the spiritual life. While we might make the connection between lambs and sheep with the Good Shepherd or John the Baptist’s proclamation, can we direct our attention towards Revelation 21 and Van Eyck’s “Adoration of the Mystic Lamb”? These adventures in symbolism are not intended as an aesthetic formation program for the intellectually elite. The ordinary Catholic’s imagination is formed when he is able to connect the natural and supernatural symbolism, such as that might exist in the iconography of a parish church. By viewing and reflecting upon the symbolism, a person vies to integrate the supernatural meaning into the daily life of home or workplace.

In preparing for the New Evangelization, the formation of the imagination is an essential element in preparation for the preaching of the Gospel. By preparing young Catholics to Look Out into the natural world, and more importantly, to play, observe, poke around and mess with the natural world, they will experience and store in their imaginations the shapes, sizes, textures, sounds, tastes and smells of all the stimuli they encounter. By encouraging young Catholics to Look In, the images in their imaginations can assist them in understanding symbols, similes, metaphors and allegories that they will encounter in authentic religious art, in reading Scripture, in participating in the liturgy. Natural contemplation, that ability to gaze and reflect, will embolden them to seek higher and deeper. Christ has promised that he will make all things new, and we can have confidence that the imaginations that may have become atrophied by secularization can be rejuvenated so we may join St. Paul in praying “Glory be to him whose power working in us, can do infinitely more that we can ask or imagine; glory be to him from generation to generation in the Church and in Christ Jesus for ever and ever. Amen” (Eph 3:20).

[1] Robert Macfarlane, Landmarks (New York: Penguin, 2016), 324.

[2] Conrad Pepler, Riches Despised (New York: Herder, 1957), 68.

[3] Charles Schulz. Accessed from: http://www.peanuts.com/search/?pubdate=&sort_by=bydate&seasonal=&startdate=&enddate=&selectcharacter=&keyword=coat+hanger&type=comic_strips#.WIUVxlMrKM9

[4] Pepler, op. cit., 69-70.

[5] Roger Ekirch, At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past (New York: Norton, 2005), 202-203.

[6] Andrew Sullivan, “I Used to Be a Human Being,” New York Magazine, 19 September 2016, accessed from: http://nymag.com/selectall/2016/09/andrew-sullivan-technology-almost-killed-me.html

[7] Roger Scruton, Beauty (New York: Oxford UP, 2009), 191.