Not long ago, I published an essay celebrating the work of the Catholic poet and literary biographer, Paul Mariani. It was occasioned by the appearance of his book, to be his final prose collection, called, The Mystery of It All, wherein he offers a compelling account of the vocation of the Catholic poet. I had written about Mariani’s work before, and have been reading it for two decades, and so have frequently referred to him as one of the few authentically and admirably confessional poets of our day.

If you should have heard that term, “confessional poetry,” before, I would not be surprised; in fact, we hear it used, not always admiringly, to describe some of the main impulses in American lyric poetry over the last half century. During that time, American poets have often restricted their work to an indiscrete and indulgent self-disclosure; they confess whatever is oddest, weirdest, or most perverse in their life story so that the thrill of the poem is, typically, limited precisely to the shock of scandal, the itch to the ears. The first so-called “confessional poet” was Robert Lowell, whose self-fascination was brilliantly interwoven with a poetry of intellectual and formal complexity; over several decades, however, such poetry became not merely embarrassing because of its content, but embarrassing because it had no substance or quality of any kind except for that of shamelessness. To many, it has seemed a juvenile butt-end to the long romantic quest for individual authenticity and self-expression, one that grew the more exaggerated the clearer it became just how little self most poets actually had to express.[1]

Mariani stands apart from this. His poetry, as explained in my essay, restores the term “confessional” to its sacramental significance. It is not a secret diary blown open by the wind or a police blotter plunging downward in a column of newsprint, as it were, but a prayerful record of self-discovery made in the presence of God. Saint Augustine’s Confessions is the most obvious antecedent alongside those distinctly modern features of his poetry that come from Lowell among others. I return to Mariani’s work, once again, because his own discussion of the vocation of the Catholic poet seems such a fruitful point of departure in answering the question, what must the Catholic artist do, in our day or in any day?

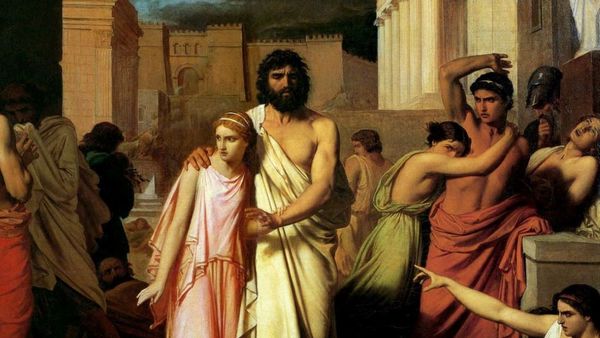

For his answer, Mariani draws our attention finally and above all to the example of Saint Paul, and to surprising effect. In the very center of the Acts of the Apostles, we watch as Paul comes to Athens; he finds a great “market place” of ideas, where “Epicurean and Stoic philosophers” meet him amid the Jews and gentiles of a city that, as Paul himself proclaims, must be “very religious” (17:18; 22). Very religious indeed, as the city is chock full of idols; their various devotions are multiplied by their decadent curiosity, which Luke describes by recording that “all the Athenians and the foreigners who lived there spent their time in nothing except telling or hearing something new” (Acts 17:21). This is not the Athens of Plato, where the question of philosophy was a question of life and death, but the Athens of the Roman Empire, where Roman curiosity has become a kind of indulgent decadence, a place where interest in ideas was only increased by a doubt that any of them finally were to be credited and adopted. They had an interest in wisdom but little hope that anyone actually could be wise.

These pagans had, however, arrived at an intellectual maturity, where philosophical reflection had deepened traditional religion until the bold natural theology of Aristotle, with its prime mover and final cause, and Plato’s absolutely transcendent Good, understood as one god, supreme, father of all, had become something like the common sense of all educated persons.[2] They represent therefore an unfortunate but familiar coupling: genuine intellectual sophistication, rigorous refinement, and decadent unseriousness.

Saint Paul, as he comes to address these pagans in the Areopagus, appeals to both dimensions of their character. To their sound metaphysics and natural theology, he proclaims that the “unknown god” at last has been given a name and may be known to each person most intimately: “The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth . . . is not far from each one of us, for ‘In him we live and move and have our being’”(17:24; 27-28). More subtly, he corrects their clever unseriousness, by wryly observing, “I perceive that in every way you are very religious,” and by provoking them to recall that, beneath decadent curiosity, lies a genuine eros to know the truth and to be saved, to “seek God, in the hope that they might feel after him and find him” (17:22; 27).

Paul is in every classical way a fine maker of speeches. He is generous even in his irony; he shows himself learned, quoting Epimenides and Aratus, to indicate that his Christian religious proclamation is the answer to pagan metaphysical questions: we are sprung from a Father who is real, unlike the scandalous mythical Zeus, and who is the cause of being. He retells the story of the world so that the pagan cosmos comes to be understood in terms of Christian creation. It is an amazing moment that millennia of commentators have understood to show Christian grace and revelation as the fulfillment of what the pagans could know by nature: the order of the world, and the naturally insatiable—but nonetheless truly natural—yearning of every human being to be saved through communion with the source of all being.

We hear that Dionysius the Areopagite, among others, heeds Paul’s words (17:33). As you will know, centuries later, a Greek monk will write under the pseudonym, Dionysius, and elaborate what Paul had begun. Pagan reason and metaphysics are illuminated and completed by Christian supernatural revelation to give us several of the most perfect and influential works of philosophical theology the world has known, above all, Dionysius’s Divine Names and Mystical Theology. Western Christians no longer accept these works as historically authentic, though Eastern Christians do, but their authority for much of the Church’s life, including for Saint Thomas Aquinas, was immense. Furthermore, they remain intrinsically authoritative, because of their merit, even if they are no longer believed to be the work of that ancient disciple of Paul’s.[3] I mention them for a specific reason, however. They suggest that later Christians understood the significance of this moment as unambiguously great, even decisive, for the spread and deepened understanding of the Gospel.[4] Yes, Paul was “mocked” by some of those present at the Areopagus, but, in making this speech that draws into a single tradition pagan philosophy and Christian theology, the natural and imperfect had been fulfilled and strengthened, while the impossible, supernatural surprise of God’s self-revelation became intelligible to the many, to the pagan world, by way of a pagan philosophical vocabulary (Acts 17:32). The works of Pseudo-Dionysius put a crowning apostolic imprimatur on this meeting of Athens and Jerusalem, one already developed by such great figures as Saint Justin Martyr and Saint Augustine, and indeed among Fathers of the Church too numerous to mention.

On this tradition, pagan philosophy helps us to understand Christian doctrine more richly and fully, even as Christian revelation inseminates and interiorly transforms the pagan until it becomes something altogether new, until pagan thought becomes what it desired but could never attain on its own: what it knew by way of metaphysical shadows, but which it now hears with the awakened ear of faith and already sees like a brilliant, a glorious, face through the darkened reflection of a mirror (1 Cor 13:12).

That last sentence borrows a figure from Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians. As Mariani retells the story of Paul in the Areopagus, he reaches toward an opposite conclusion and a different lesson to be found in another verse from that same letter. According to Mariani, Paul leaves the Areopagus “defeated.”[5] His attempt to present the Gospel in learned pagan terms has been met with laughter. The Acts of the Apostles tell us that Paul then left Athens for Corinth (Acts 18:1). According to Mariani, Paul would also leave behind his attempts to be a clever philosopher. There Paul preaches that “the cross is folly” to those who think themselves wise and clever, to the gentile or Greek (1 Cor 18-19). Mariani also quotes Paul’s vow, as it were, from the second chapter of that letter: “I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Cor 2:2). Paul explicitly renounces all pretensions to wisdom, meaning quite specifically the philosophy of the Greeks, and reserves to himself only the death-to-self transformation wrought in his own life by the work of the cross.

The lesson Mariani draws is clear. Christianity will only be mocked, if it enters into the intellectual, philosophical, and poetic fabric of the pagan world. The cross may well be the fulfillment of that world’s philosophical intuitions, but it will always appear as foolishness and folly, and will be scorned for its pretension rather than embraced for its intelligence, so long as it seeks to enter into the agora of classical metaphysics, wisdom, and intellectualism. All one can do is profess the personal knowledge, to know Christ; not the hypothesis of seeing face to face, but one’s encounter with the actual face of the Crucified One. To do so is to confess. Mariani’s poetry is to be celebrated as confessional in just this sense: it testifies to a personal encounter, in some sense stripped of artifice and cleverness and philosophical explanation. Appeal to what one’s auditor already knows will come to vanity or foolishness. We can only confess the cross and what it has done to us, to we who stand before, and speak, and offer nothing but ourselves transfigured by grace.

This is a plausible argument. Paul rarely speaks again, in Acts or in his letters, as he does in the Areopagus. A central theme of his letters is just this phenomenon of confession, namely, the assumption-overturning role of grace and faith, in Romans; the primacy of union through personal love, in 1 Corinthians; and above all the death to self through transformation in Christ, which is the central theme in 2 Corinthians and Galatians, where Paul confesses himself a fool for Christ, by which he means, all he knows and all he is comes through being “crucified with Christ” (2 Cor 11:18; Gal 2:20). He is the last and least of the apostles; it is not his teaching, his baptism, but Christ’s; he cuts a pathetic figure—as why should he not?—for he has gone from being a tent maker to become an empty tent in which to bear through the world the news of the New Covenant.

But this is not the whole story. The letter to Colossians all but begins with a Christological meditation that reads like the speech in the Areopagus in little:

He is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation; for in him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or principalities or authorities—all things were created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together (1:15-18).

It is incorrect, therefore, to suggest Paul only spoke in this manner, which puts Christ at the center of metaphysical wisdom, but once. In fact, he builds upon and deepens the insight of Acts 17 here, drawing Greek wisdom and the cross together by saying,

For in him the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross (Col 1:19-20).

Paul also writes to the Ephesians of a cosmos and an entrance into wisdom through Christ similar in substance to Colossians and the Areopagus speech (1:10, 1:17; 3:9, and to a lesser extent, Phil 2:10 and 4:8 ff.). At the least, we may affirm that Paul played philosopher more than once.

In Acts as a whole, we see three kinds of rhetoric that argue in favor of faith in Christ. In the early chapters, Saints Peter and Stephen speak to their fellow Jews, and prove Christ by appeal to the scriptures and the prophets (1:15 ff.; 2:14 ff; 3:12 ff; 7:2). Paul follows their form, initially, after his conversion (13:6ff). In the middle of Acts, we have the philosophical account directed to a pagan or gentile audience, in the Areopagus. But, thereafter, as Mariani indicates, a new rhetoric appears, no less directed at gentiles, but whose substance lies entirely in testimony or confession of the transformation that has been wrought in Paul himself by Christ. These most powerful arguments are therefore acts of martyrdom, a bearing-witness that Paul has died in Christ and now confesses Christ’s power only by his preaching death-in-life.[6] To read these three modes of rhetoric as attempts that get tried and discarded until Paul, at last, knows and speaks but one thing, the cross of Christ, would seem contrary to the meaning of Acts and how the tradition has received it. We see rather the apostles doing just what Paul says he has done in still another passage in 1 Corinthians: “I have made myself a slave to all, that I might win the more . . . To the weak I became weak, that I might win the weak. I have become all things to all men, that I might by all means save some” (1 Cor 9:19; 22).

I propose that Paul testifies most powerfully to his myriad-minded becoming all things in his speech on the Areopagus. For, there, he perceives a pagan people, mature and intelligent of culture, but compromised by disillusion, because the primordial truths they have come to understand with sophistication cannot be fulfilled by nature or reason alone. The truth has been known too long and grown too old, and those familiar with it have grown bored, disillusioned, and cynical. They think themselves occupying a decadent afterlife, like the sybil, but in fact, all this time have awaited, without knowing they awaited, the coming into history of their fulfillment. Paul does not simply climb Mars Hill, he strides into the center of the plane of being, the place where all things that are have their intelligible existence, and preaches Christ first in the language such a place can understand. In doing so, he in a sense redeems nature. All that was already known is retained and, indeed, transformed and lifted up, so that it may not be lost but saved and fulfilled. To turn pagans into Christians, he has first to know what the pagans know better than they themselves know it. He has to remind them of what they know in such a way that they can see it for the first time—and see the unmapped center which they must now explore.[7]

At the heart of Paul is indeed his own transformation, his own, humble, self-emptying confession. But, flowing out from that, as from the very center of reality, comes an ability to speak to the pagan, by way of the pagan’s philosophy and culture, and so to master what is widespread and familiar even while transforming it with his own profound insights. As I look back at Mariani’s work, and the work of those he admires, I see a similar union of confession and metaphysical savvy, of martyrdom and philosophical wisdom. I am glad to acknowledge as much, because I believe we have to learn from Paul’s speech in the Areopagus and to apply its lessons in our age that in some ways resembles a decadent, cynical Roman world, but is in at least one way frighteningly different.

Alice von Hildebrand once recalled an encounter her husband had with a friend in the chaotic and confusing wake of Vatican II:

A friend happened to tell my husband, “I am afraid that we are going back to paganism.” I shall never forget his speedy reply: “We cannot go back to paganism; the pagan world lived ante lucem; those who have received the light of revelation and reject it are not and cannot be ‘pagans’–they are ‘apostates.’ And, apostasy is worse than paganism.”[8]

Such indeed is our age. It is apostate, having rejected the supernatural light of Christ. But, further, it is apostate, because it has also rejected the natural light of being. The ancient pagans, whom Paul accosted, had also all but lost the light of being.[9] They had come to take for granted the wisdom of Plato and Aristotle to the point that they were truisms, but they had also become incredulous and contemptuous. Their ravenous curiosity was not founded on any fundamental trust that a philosophical appetite might finally be slaked by a true knowledge of being.

It is my argument that the Christian artist must implicitly begin, as Mariani insistently begins, in the interior self-knowledge that springs forth on the lips of the Christian as testimony, confession, martyrdom. But we have also to re-explain the age to itself, to re-teach it, that is, to trust in the capacity of reason to grasp the truth and to treat its wide ranging inquiries not as a collection of amusing baubles, but as clues to salvation. We have to re-teach the age to trust the light of being, already before its eyes, for only then may the transformative word of the cross make an entrance.[10] And so, Paul’s speech in the Areopagus is not failed rhetoric, but the very model of our rhetoric, re-awakening our auditor to what it already in some way knows and then, by bearing witness to the cross, deepening that knowledge, before at last fulfilling it with something categorically new, the revelation of the face of Christ.

Before moving forward, I need to further sketch what this should entail. Confession, as Paul knew, was a highly efficacious rhetoric just as was the command of philosophical wisdom and culture. So, we should acknowledge not only that power but that power as specifically rhetorical. To speak of the speech in the Areopagus as a model for the Christian poet or artist, then, we mean something more. Just as pagan wisdom drives at being, at the metaphysical sub-structure that discloses the nature and relation of all that is, so does its rhetoric, by analogy and allusion, seek after an aesthetic form that is at once refined, intricate, complex, profound, and comprehensive. Its appeal lies not primarily in a depiction of the interior dramatic form of the soul and its story, but in the overall ontological form of things as a whole. It is cosmic rather than confessional, and finds early expression, perhaps, in the poetry of Hesiod, but most definitely in the great palinode of Socrates that lies at the center of Plato’s Phaedrus (242d-257b), where to discover the soul is above all to discover the order of reality as a whole into which our being with its yearning is fitted, and in whose fullness of knowledge alone it may pasture in happiness.

Such rhetoric emphasizes not primarily who one is, but the fundamental reality of what things are. Its relation is not between the soul confessing and the soul listening, but between the elegant pageant of aesthetic form and the great circle of created being, of ontological form. If this level of abstraction does not clarify, then simply consider Dante and what has always fascinated us about him. George Santayana suggested that Dante was the true religious poet precisely because he could give us a vision of “cosmic order,” and Santayana contrasts him with Shakespeare, whose interiorized psychological complexity entails conversely a comparative absence of religion.[11]

With this vision fleshed out somewhat, let us turn to the actual practice of poetry. Mariani is first a confessional poet and so we may not be surprised that among his most powerful poems are just those that bear witness to what has been done to him and within him. Although I could choose from many, I would like to offer a late poem, “Quid Pro Quo” as exemplary in this regard. In the poem, we hear of Mariani, the young graduate student and adjunct professor in Manhattan, in the early days of marriage to his wife, Eileen. Eventually they will have three sons, the oldest of whom, Paul Jr. will become a Jesuit priest. But, as this poem begins, the deliverances of fatherhood are themselves in miserable doubt:

Just after my wife's miscarriage (her second

in four months), I was sitting in an empty

classroom exchanging notes with my friend,

a budding Joyce scholar with steelrimmed

glasses, when, lapsed Irish Catholic that he was,

he surprised me by asking what I thought now

of God's ways toward man. It was spring,such spring as came to the flintbacked Chenango

Valley thirty years ago, the full force of Siberia

behind each blast of wind. Once more my poor wife

was in the local four-room hospital, recovering.

The sun was going down, the room's pinewood panels

all but swallowing the gelid light, when, suddenly,

I surprised not only myself but my colleagueby raising my middle finger up to heaven, quid

pro quo, the hardly grand defiant gesture a variant

on Vanni Fucci's figs, shocking not only my friend

but in truth the gesture's perpetrator too. I was 24,

and, in spite of having pored over the Confessions

& that Catholic Tractate called the Summa, was sure

I'd seen enough of God's erstwhile ways toward man.That summer, under a pulsing midnight sky

shimmering with Van Gogh stars, in a creaking,

cedarscented cabin off Lake George, having lied

to the gentrified owner of the boys' camp

that indeed I knew wilderness & lakes and could,

if need be, lead a whole fleet of canoes down

the turbulent whitewater passages of the Fulton Chain(I who had last been in a rowboat with my parents

at the age of six), my wife and I made love, trying

not to disturb whosever headboard & waterglass

lie just beyond the paperthin partition at our feet.

In the great black Adirondack stillness, as we lay

there on our sagging mattress, my wife & I gazed out

through the broken roof into a sky that seemedsomehow to look back down on us, and in that place,

that holy place, she must have conceived again,

for nine months later in a New York hospital she

brought forth a son, a little buddha-bellied

rumplestiltskin runt of a man who burned

to face the sun, the fact of his being there

both terrifying & lifting me at once, this son,this gift, whom I still look upon with joy & awe. Worst,

best, just last year, this same son, grown

to manhood now, knelt before a marble altar to vow

everything he had to the same God I had had my own

erstwhile dealings with. How does one bargain

with a God like this, who, quid pro quo, ups

the ante each time He answers one sign with another?[12]

The raw flesh of confession in this poem, where the poet does not even dare to propose that he understands what Christ has done in him, because it is no longer he who lives, but Christ, is palpable and powerful, not to mention Pauline. It is not Mariani’s only kind of rhetoric, however. Like this one, many of his poems are restrained narratives, almost like a gloss or commentary that resists some of the conventional intensities typical to the lyric poem from its ancient inception and most richly realized in the 17th century metaphysical poets and the romantics of the 19th century.

Sometimes, that almost scholarly distance serves specifically to give him leave to speak a bit like Paul in the Areopagus. For instance, in the title poem from his book Prime Mover, he takes Geertgen’s “Virgin and Child” as occasion to paint a metaphysical portrait of the cosmos. The painting has at its center the Blessed Virgin and infant Christ. Behind them, a bright golden center of light. All about them, ranged in concentric circles, are the orders of angels equipped with different items: the instruments of the passion, in the second, and, in the “outermost,” “the number of angels who blare out in wonder / the news of the ages in a heavenly music” on lute, bagpipe, horn, shawm, and clapper.[13] We see three circles entire, and part of a fourth, because they disappear into darkness and the limit of the painting; they exhaust the limits of being. The poem is ekphrastic; the painting serves as occasion for the poet to reflect on history, as if it radiated doubtfully out from that golden center. That the painting’s orderly symbolic depiction is akin to the spiritual geography found in Dante’s Divine Comedy is no coincidence. By meditating on this painting, Mariani gives himself occasion to offer a true Christian metaphysics, but one kept in the cautionary scare quotes, as it were, of its being a commentary on a medieval painting.

We see similar movement between confession and metaphysical capaciousness in Mariani’s dearest poet, the 19th century English Catholic convert and Jesuit priest, Gerard Manley Hopkins.[14] Most readers of Hopkins will identify him with an emphatic, almost speechless, stuttering confession of awe before the God he finds just barely veiled within the created thisnesses of nature. Such we see most memorably in “God’s Grandeur”:

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil.

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge and shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.And for all this, nature is never spent:

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

The most prominent features of Hopkins’ poetry roughen its metrical surface not only with unusual rhythms, but with alliterations and violent pauses and enjambments, all of which serve to give voice to his fumbling, tongue-tied, and earnest awe, an awe that sometimes gives way to a mere sound—an “Oh”! —and then, when peace and fulfillment and redemption are at last at hand, a sigh—“ah!”—to end all.

These features should not lead us to ignore the metaphysical complexity or insight of the poem, however, which feature most prominently in the two far-flung similes that start the poem; the implication that the fall of nature is deepened by man’s industrious depredation of the natural world; and, above all, by the layered allusion that runs through his reference to the dawn as “brown,” meaning “russet,” and so alluding to Hamlet (II.i.166-167), where Horatio announces, “the morn, in russet mantle clad, / Walks o'er the dew of yon high eastward hill.” This in turn alludes to John’s gospel’s depiction of the risen Christ, whom Mary Magdalene at first mistakes for a humbly dressed gardener (20:11-16). The poem’s texture seems as if it were aimed at emotive, direct speech, but in fact it weaves through history with intellectual agility and with a polysemantic, allusive depth.

Hopkins’s later sonnet, “To what serves Mortal Beauty?” displays a similar metaphysical and historical agility. It runs in full:

To what serves mortal beauty ' —dangerous; does set danc-

ing blood—the O-seal-that-so ' feature, flung prouder form

Than Purcell tune lets tread to? ' See: it does this: keeps warm

Men’s wits to the things that are; ' what good means—where a glance

Master more may than gaze, ' gaze out of countenance.

Those lovely lads once, wet-fresh ' windfalls of war’s storm,

How then should Gregory, a father, ' have gleanèd else from swarm-

ed Rome? But God to a nation ' dealt that day’s dear chance.

To man, that needs would worship ' block or barren stone,

Our law says: Love what are ' love’s worthiest, were all known;

World’s loveliest—men’s selves. Self ' flashes off frame and face.

What do then? how meet beauty? ' Merely meet it; own,

Home at heart, heaven’s sweet gift; ' then leave, let that alone.

Yea, wish that though, wish all, ' God’s better beauty, grace.

The poem begins with a premise that seems to reject all sensible artifice. Mortal beauty is in question, because it is “dangerous,” it sets the blood “dancing” without necessarily ordering the steps to the Good. The frenetic, palpitating, because interrupted and stuttering, syntax would seem to indicate such a purely emotive movement of blood dancing with a heightened pulse.

Hopkins’s poem, however, leads us on a zigzagging dialogical reflection that runs as follows: yes, mortal beauty sets off the pulse, its form seeming final and perfect, and more proudly independent or autonomous than a Purcell tune (ll. 1-2). But it also keeps the mind (“wits”) alive or sensitive to being, to the meaning of goodness, and does so quickly rather than by way of concentration and thought (ll. 3-5). This abstract observation echoes Plato’s Phaedrus, but then Hopkins turns from philosophy to history, from the universal to the particular, recalling a story from Bede’s History of the English Church and Peoples. Pope Gregory sees Angles lined up in the slave market in Rome, brought there by chance, by “windfall.” He would not have noticed them within the swarm of the Roman streets but for their angelic beauty (ll. 6-8). God thus brought salvation to a people by a chance glance, as Gregory then ordered a mission to the British Isles; they are a chosen people (ll. 8).

Men once worshiped pagan idols, who are merely mortal beauties, because wrought of stone; but the law of Christ tells us to love what is more worthy than matter, spirit—and the highest spirit in the world is the self of a man (ll. 9-10). Selfhood is mortal; it has a flashing beauty; and yet has an intrinsic goodness, a worth (l. 11). What are we to do with this danger, then? Because the self is the highest natural beauty, Hopkins tells us, echoing Aquinas, who says personhood is the highest creature in nature, we must “meet” mortal beauty as one meets a person (l. 12).[15] We recognize beauty (we “own” it), as one recognizes a face, and this echoes Plato’s thesis in the Phaedrus that mortal beauty initiates a re-collection (anamnesis) of the eternal beauty (l. 12). We see the beauty of a person, here in the world, and it stirs the soul to recall the eternal beauty in the place of being. We must receive this meeting in the heart as a gift, but do not “own” it as our own; we must not try to possess it (l. 13). This disinterest preserves us, and leaves us free to desire something else much harder, indeed with all our being, to “wish” for the immortal beauty of God’s grace (l. 14). What seems at first a poem clotted by earnest confession is in fact an intricate philosophical dialogue. What seem the stutters of one overwhelmed by problem are actually the telegraphed movements of an argument. Not that these are mutually exclusive, but they are not the same thing.

To look back to a poet who has inspired Mariani and Hopkins alike, the metaphysical poet of the 17th century, George Herbert, we find a similar alternation between confession and metaphysical wit. Samuel Taylor Coleridge was not the only later reader to find in Hebert an earnest simplicity of devotion.[16] T.S. Eliot would later judge Herbert a minor poet, because, though there was a beauty of confession to his work, it was devotional and personal rather than metaphysical and comprehensive.[17]

In Hopkins’s most celebrated poems, this may seem plausible. “The Collar” is powerful primarily because of its frustrated confession. A good number of poems, including “The Pulley,” are allegorical and so have a kind of didactic simplicity that leaves untouched the foundational struggle with belief that Paul, in the Areopagus, was so good at reinterpreting to the pagans. And yet, in Herbert’s “Love I” and “Love II,” we hear Herbert explaining his poetic practice. He knows well that, as the world is, the poetry of wit is largely devoted to impressing the intelligence of those mortal beauties we know as women. In his work, he seeks to draw such “lesser” intellectual light to the service of God’s “greater flame.” That is, he would have “our brain / All her invention on thine Altar lay.” This is not to sacrifice wit, the philosophical intelligence that makes analogies among beings, but rather to baptize it, to offer it up and gather it in.

So have I tried to do in my own work. Taking Dante as an example, I have tried to compose a poetry that looks first to the order of things and asks the reader to move with the intelligence from metrical form (meter), to metaphorical forms (analogies), and on to perceive the deep analogy between the well made thing, the being of the cosmos, and the ground of being that is God.

Let me close by offering just one example, the final section of my long poem, The River of the Immaculate Conception, which is a meditation on the nature of the fine arts in relation to the sacred art of the liturgy, and the relationship of both these things to the divine ideas that we yearn by our most earthly natures to ascend to and to know.

VII. “Hasten to aid thy fallen people”

How does one make a song of holiness?

Or speak of music without spoiling it?

They both seem more than our tongues can confess

And, born above, in our world do not fit.

What’s more, those who ascend with them

Are closed in on themselves, struck dumb,

And all in ecstasy that they have heard

Seems flailing, foolish in a fallen word.

But every rising strain must strain indeed

To lend a form to what in truth is light,

And manifest peace as if it’s a deed

And give transcendence some arc of a flight.

The purity of every saint

Will be daubed on with sloppy paint,

And what no thought may comprehend or say

Must be taught in the staging of a play.

The gift of form, because so fascinating,

As we bend down to work with knife or ruler,

Reminds us that beyond it’s always waiting

Some piercing light. Consider how the jeweler

Makes every cut upon a stone

For its sake but not that alone,

His patient labor wasted if a line

Does not refract and multiply and shine.

And, any humble implement may serve

To figure-forth and yet conceal that light,

So that high thought is felt upon each nerve

And mystery is given to our sight.

Just this way, things are lifted up:

A chalice wrought from wooden cup;

A little dust and water, mixed to clay,

Are molded into birds that fly away.

The Mass is first His earthen sacrifice,

But also taste of peace and heaven’s throne,

The gift that leaves behind all thought of price

Yet where, no less, we raise a plangent groan,

For at its finish we are sent

Into the world both dark and bent

That bearing out the Virgin’s hastening aid

From ruined choirs some good may be remade.

[1] See: Frederick Turner, “Lyric and the Content of Poetry” in Think 5.2 (Spring 2015): 69-82.

[2] See: R.L. Wilken, The Christians as the Romans Saw Them (New Haven: Yale, 2003), 106.

[3] See, Benedict XVI, “Pseudo-Dionysius, The Aeropagite” General Audience 14 May 2008.

[4] Cf. Joseph Ratzinger, Introduction to Christianity (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2004): 137-143.

[5] Paul Mariani, The Mystery of It All, 31.

[6] Peter anticipates this himself in Acts 10:34, which emphasizes Apostalic “witness” (10:41). Paul preaches in Acts 22 and 26:4 ff.

[7] Hans Urs Von Balthasar, Epilogue (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1987), 17-18.

[8] Alice von Hildebrand, “A Plea: Back to Socratic Paganism.”

[9] Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1998) 1.18-19.

[10] Ibid., 1.145.

[11] George Santayana, Interpretations of Poetry and Religion (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1989), 91, 167-168.

[12] Paul Mariani, Epitaphs for the Journey (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2012), 81-82.

[13] Paul Mariani, Prime Mover (New York: Drove, 1985), 78.

[14] Mariani, The Mystery of It All, 12.

[15] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica I.29.3.

[16] S.T. Coleridge, The Major Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 556.

[17] T.S. Eliot, Essays Ancient and Modern (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1936), 96. This judgment would not last; he would later acknowledge Herbert’s centrality to the canon.