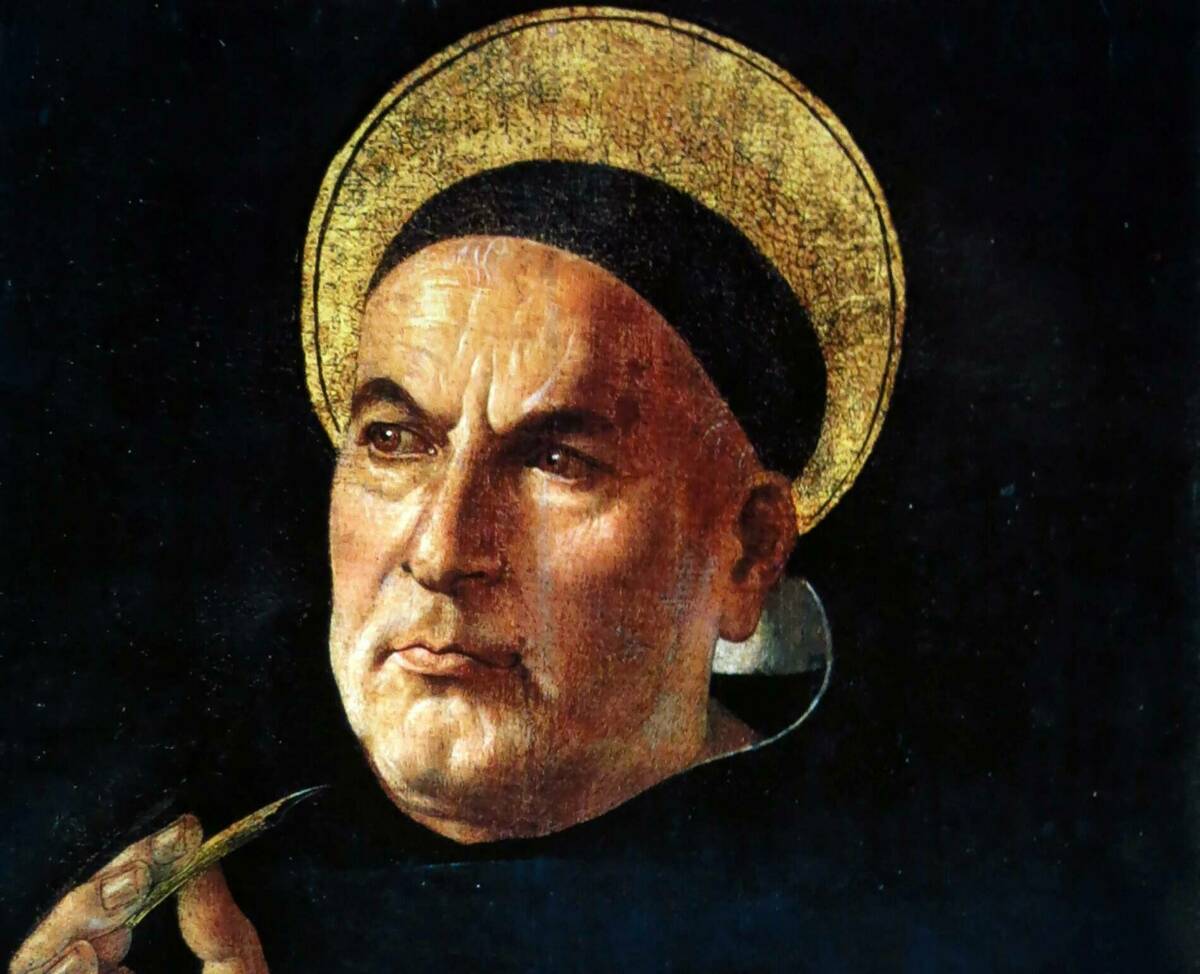

St. Thomas deals with free will and impeccability on several occasions: first, around 1254–1256, in his commentary on the second book of the Sentences; then, in 1258 or 1259, in the De Veritate; around 1259–1261, in the third book of the Contra Gentiles; around 1265–1268, in the first part of the Summa Theologica; finally, in 1270 or 1271, in the De Malo. Both because of the exceptional importance of his thought and because of the inaccurate interpretations that have been put forward, it is necessary to dwell on it somewhat, although it does not, at least as far as it seems to us, contain any serious ambiguity.

In the commentary on the second book of the Sentences, questions arise twice in explicit terms. The first time, the question is whether an angel could sin. The answer is affirmative, in accordance with a principle which does not allow for exceptions:

Only the will whose nature is the sovereign goodness in itself, which is the rule of the will, is entirely impeccable. But any other will can act against this rule. So in the will of the angel there can be obliqueness and sin.

As for understanding more precisely how such a sin was possible, given the perfection of the angelic nature, this can be done without abandoning the fundamental thesis that evil is dependent on error. St. Thomas explains, as a good pupil of his master Albert:

Although the angel’s intellect cannot be bound by passion in its choice, as is the case with us, it may nevertheless be prevented from judging correctly what to choose by the omission of some of the elements which should have been considered, for it does not know, by natural knowledge, all things at once . . . Such a thing is right to choose when considered in itself, which is not right when considered in relation to other elements of judgment; and thus the angel may have been mistaken as to what was right to choose, though not as to the absolute knowledge of that to which his natural knowledge extends.

No matter how clear the intelligence of the pure spirit may be—this intelligence, which is always in act, which grasps its object in a simple intuition, without words—it is not, however, free from practical error, and this is why the will, whose exercise depends on that of the intelligence, may fail in its turn.

Later, in the case of Adam’s sin, the general principle is recalled, without any restriction. A naturally flawless creature is impossible, the very concept is contradictory:

To no creature was it granted, nor could it be granted, that it could not sin by virtue of its nature. It was impossible that, while preserving its freedom of choice, it should be granted to a creature that, according to a condition of its nature, it could not sin. In effect this is like an implication of contradiction. For if there is free will, it must be able to adhere to its cause or not adhere to it; and if it cannot sin, it cannot not adhere to its cause; and thus a contradiction is implied.

And St. Thomas then shows, according to a no less traditional view, that this impossibility does not in any way constitute a limit imposed on the All-Powerful:

It is not by virtue of an imperfection of the divine power that it cannot confer on the creature to resemble it in this; it comes from the imperfection of the creature: in part because the creature cannot receive this resemblance, and in part because there is a certain impossibility in the implication of contradictory things, as we have said.

These texts are from about 1254–1256. The Question 24 of De Veritate was written, it seems, at the end of 1258 and the beginning of 1259. St. Thomas affirms the solidarity between reason and free will, the impossibility of assimilating the action of spiritual beings to that of other natures, the essential sinfulness—flexibility and evil—of every created spirit. No doubt Anselm is right not to define freedom by the power to sin; we must not forget, however, that the freedom of man or even of the angel is not that of God: for both human and angelic nature derive their principle from nothingness. Once again, the human soul and the celestial body are incorruptible; but nothing can be concluded from this for the impeccability of the wills:

There is not and cannot be any creature whose free will is naturally established in the good, so that it would be incumbent upon it merely by virtue of its natural qualities not to be able to sin. There is a reason for this. For from the defect of the principles of action there results a defect of action. If, then, there is a being in whom the principles of action can neither be lacking by themselves nor prevented by something external, it is impossible for its action to be lacking: this is what is clear in the movements of the heavenly bodies. But the actions of those in whom the principles of action can fail or be thwarted, as we see in the creatures that can be begotten and corrupted, can fail in their actions. Now reasonable nature endowed with free will differs in its action from any other active nature.

A reasonable nature, which is absolutely destined for good by means of multiple actions,

cannot naturally have actions that do not fail to be good if it does not naturally and immutably possess a value of universal and perfect good, which can certainly exist only in the divine nature. For God alone is pure act receiving no mixing of any possibility and is therefore pure and absolute goodness. But any creature, having in its nature a mixture of possibility, is a specific good. Now this mixture of possibility comes to it from the fact that it is drawn from nothingness. And from this comes the fact that among reasonable natures God alone possesses a free will naturally impeccable and confirmed in the good.

It would be difficult, one would agree, to be clearer. It should be noted that St. Thomas, as he already did in the Sentences, always reserves the case of a nature which, by extrinsic privilege, would be confirmed in grace. But this would not be a metaphysical exception to his principle, for it would not be the case of a nature considered as such. Hence this insistence: “Impeccable by nature,” “By nature, not deficient in the good,” “Confirmed by nature.” Hence once again this analogous formula, which is typical of him, and which was common in his time: “By its pure natural qualities” or “in its pure natural qualities.” The formula (which we will find again later) will remain in theological language for a long time, but its meaning will change completely. It is not the place here to outline the history of this change or to seek an explanation for it. It will suffice, in order to support our remark, to set against the repeated assertions of St. Thomas and his first disciples, according to which the angel or any other created spirit could not be impeccable “By its pure natural qualities” or “in its pure natural qualities” or “considered in its natural qualities,” the following statement of John of St. Thomas: “The angel, considered in his pure natural qualities . . . cannot sin.” Unless we admit—and this would be excessive—a total opposition of doctrine between the Angelic Doctor and his illustrious commentator, we must recognize that the words no longer have for the latter the meaning they had for the former.

***

Around the same time, towards 1259–1260, or perhaps at the latest, in 1261, St. Thomas resumed, in the third book of the Contra Gentiles, the examination of our problem. It is not surprising to see that he develops the same doctrine there as in the De Veritate. However, he will show himself to be both more original in his style and more concerned to exploit the resources of St. Augustine’s teaching on moral goodness. Once again, it is about the sin of angels. The three chapters he devotes to it appear to be already constituted as an article of the Summa: after the objections, which pose the problem in all its acuteness (c.108), comes the doctrinal exposition (c.109), followed by the particular answers (c.110).

The two essential objections are always the same. They demanded special attention in a work written for the “Philosophers.” The technical objection: perfection and simplicity of the intelligence, preventing the error necessary for sin; the principled objection: the ideal of perfection, according to the analogy of the heavenly bodies. It is a fact, however, that demons have sinned, since there is no naturally evil creature. If one follows the opinion of the Platonists that demons have an aerial body, the explanation would be easy. But, admitting that they are, like the other angels, entirely spiritual substances, thereby forbidding the possibility that they could have been mistaken in their own good. It is therefore elsewhere that one must seek the origin of their fault: “There may have been sin in the will of a separate substance, because it did not set its own good and perfection on the last end but attached itself to its own good as an end.”

Not that any spiritual creature can desire, in the proper and direct sense, equality with God: they would see that this is impossible, and besides, how can they desire what would be their own destruction? Nevertheless, this is indeed, in a certain sense, according to the word of Isaiah, the malice of Satan’s sin, which was a sin of pride: “To want to regulate others without allowing one’s own will to be regulated by a superior will is to want to command and, in a way, not to be subjected.” The explanation is exactly the same as the Augustinian analysis of the superbia. By a roundabout way, it returns to the one given by St. Anselm. Man can sin in two ways: by the revolt of the lower appetite against the rational will—and this cannot happen in pure spirits—but also and above all “by the fact that the human will does not direct its own good to God, which indeed is a common sin both to itself and to separate substances.”

In God alone such a deviation is impossible. And so in terms of finality one finds the same fundamental thought that the commentary on the Sentences gave in terms of a rule of action. Only, the quasi-Kantian formula inherited from Anselm of Canterbury now gives way to a finalist explanation, more purely Augustinian in inspiration:

Every will naturally wills what is the proper good of him who wills: that he should be perfect; and it cannot will to the contrary. Therefore no sin of will can occur in an act of will on the part of him whose proper good is the last end which does not come under the order of any other end but under the order of which all other ends come under. Now this will is God, whose being is the sovereign goodness which is the last end. Therefore, in God there can be no sin of will. But in any other will, whose proper good must necessarily be placed under the order of another good, sin can occur to the will if it is considered in its nature. Although there is, indeed, in every will a natural inclination of the will to desire and love its own perfection, in such a way that it cannot desire the contrary, yet this inclination is not given to it by nature in such a way that it regulates its perfection on this other end to the point of not being able to miss it: this is because the higher end is not proper to its nature but to the higher nature. It remains, therefore, for man’s judgement to adjust his own perfection to the higher order.

The answer to the objections sheds further light. To the technical problem of the perfection of the angelic intelligence, St. Thomas now answers in a slightly different way than he did at first after St. Albert the Great:

We are not reduced to saying that there was an error in the intelligence of the separate substance in judging as good what was not good, but it was in failing to consider the higher good to which its proper good ought to relate . . . The sin consisted in this, that it neglected the higher good to which it should have regulated itself. . . . In the devil, the sin consisted in not relating his own good to the divine good.

There is therefore no error, strictly speaking—Aristotle’s letter is better respected than Albert’s distinctions—nor is there the height of malice and lucid absurdity that would constitute a revolt willed for its own sake in full light, which would be pure voluntarism. But simply, in negative terms: non-consideration, non-ordination; preterition. More guarded language, but in substance, one can well say, the same solution as in the commentary on the Sentences.

The objection of principle is more brutally dismissed. All parity between angels, who are spiritual beings and therefore essentially free, and heavenly bodies is rejected. The latter are assimilated to the “bruta animalia, the beasts,” and the word of John Damascene, which has become a commonplace, is applied to them: “They are led, they do not lead themselves.” They have no will in the proper sense, but they are driven from without to their end:

Those who possess a will differ from those who are deprived of it in that those who have a will regulate themselves and their affairs to an end, whence they are said to have free will. But those who are deprived of a will do not regulate themselves to an end, but are regulated by a superior agent, as if led to an end by another, not by themselves.

Here one might evoke the doctrine so dear to St. Thomas on the “the dignity of causality” that God wished to communicate to his creature. This causal character, which makes the nobility of the created being, and which is the hallmark of its reality, consists essentially, for the spiritual creature, in being able to act on itself, by an immanent and free causality, and to give itself to its end: it conducts itself, it directs itself to an end. How can it be conceived that it can be deprived of this, carere, on account of its very perfection?

As can be seen, St. Thomas remains fully faithful to the traditional conception. The ancient ideal of necessity does not seduce him for a moment. But he takes renewed care to resolve the technical difficulty that his own philosophy had highlighted. In a sense, he grants something to the objection, no longer daring to speak, as he once did, of an error in the angelic intelligence. The angel only neglects to consider its last end, and thus neglects to connect with it. It withdraws into itself; it takes itself for the supreme end. Hence the opposition between its own good and the divine good, in which its sin consists. For, according to St. Augustine—whose teaching St. Thomas, after Peter Lombard, makes his own in slightly different formulas—there can be no true moral goodness where the intention of the last end is lacking. “It is not by their service but by their end that virtues are distinguished from vices.” The same objective acts may be “good in kind,” bad in intention.” Just as the normal exercise of the will consisted essentially in ordering itself, “The self and its affairs, according to an end,” so “the sin of the will,” which is not only disorder or objective lack, but corruption—or failure—of the intention, consists, as St. Thomas says in the De Malo, in “deviating from the end of the action.” Such, then, is the sin of the angel. It is hardly necessary to observe that no allusion is made in these three long chapters to a duality of ends, as if the angel’s sin were explicable only in relation to one of these two ends, in one hypothesis and not in the other. St. Thomas certainly does not imagine an order of things in which it would be permissible for any creature to confine itself to its “proper good” or “proper perfection” without relating it to God!

***

St. Thomas returned to the question in the latter part of his life: first in the first part of the Summa (1265–1268), then in the De Malo (1270–1271). It is in these two works that the new formulae are found, from which it has been concluded—without sufficient regard to the preceding texts, which are necessary to understand them properly—that he professed the impeccability of the angel in the hypothesis of an order of pure nature. However, it seems to me that his opinion has never changed as to the substance of the problem. In their elaboration, if not quite in their writing, the texts under consideration can be regarded as contemporary. As those of the Summa are more synthetic, they are reserved for the end.

In De Malo, q. 16, a. 3, St. Thomas investigates in what, the devil’s sin might have consisted. After having rejected, as in the Contra Gentiles and for the same reasons, the idea that the devil would have wished to make himself equal to God, he adds that, in a general way, this sin could not have consisted in anything which touches the order of nature: for in this order, the angels were established, by their very creation, in a present perfection. But as regards supernatural goods, they were created only in power. It was therefore in relation to these goods that they could sin:

And whatever more may be said that belongs to the order of nature, it may not have consisted in this. For evil is not found in what is always in act, but only where power can be separated from act. Now the angels were all created in such a way that from the beginning of their creation they had everything that pertains to their perfection. And yet they were in power with respect to the supernatural goods which they could attain by the grace of God. Thus, it remains that the devil’s sin did not consist in something that is part of the natural order, but according to something supernatural.

Basically, with a few nuances, it is the same distinction that the third book of the Contra Gentiles made. On both sides, it is a question of the “Perfection (proper)” of the creature and its relation to some reality of a higher order. But what the Contra Gentiles also called “Proper good,” the De Malo—from a slightly different point of view—also calls “that which belongs to the order of nature,” “to the natural order,” or even “its natural qualities.” At the same time, instead of “the highest end” (which returns in the Summa, and which will be in the Compendium theologiae “the sovereign good, which is the last end”), there are “supernatural goods” or “something supernatural.” But there is also no question of any hypothesis in which a created spirit would be simply impeccable. Not only does St. Thomas not even refer to it implicitly, but it was excluded in advance. Indeed, in the first question of the same De Malo, the same general principle that had already been formulated in the Commentary on the Sentences was recalled once again:

A good which is created can in some way fail through this failure from which proceeds voluntary evil, because from the very fact that it was created it follows that it is subject to something else, for example to its rule, to its measure. But if he were himself his rule and his measure, he could not set about his work without a rule. Therefore God, who is his own rule, cannot sin: in the same way an artist could not err in carving a piece of wood, if his hand were the rule of his art.

No exception is made here for any kind of spiritual creature in any “order” of Providence, any more than in the earlier works. None, of course, could be. And the following article of the same Question 16e, which continues the clarifications made in Article 3, does not make these clarifications into restrictions either. To turn to supernatural goods is to turn to God: “Converting to that which is beyond nature a conversion to . . . God.” Now, this “conversion” is indispensable to the salvation of the creature, who cannot remain enclosed in the contemplation and enjoyment of its “connatural” good; yet, in this conversion, it is always free to refuse to be converted. Thus, the principle is maintained in its universality. For St. Thomas, as for all his orthodox predecessors—whom he is aware of being in full community of thought on this point—all created spirits are naturally sinful.

In the first part of the Summa Theologica, of interest is the second article of Question 9, the first article of Question 83, and especially the first article of Question 63. St. Thomas does not add anything essential to what is already known of his doctrine, but he takes up and unites its various aspects, as if to make us understand clearly that from the Sentences to the De Malo, passing through the De Veritate and the Contra Gentiles. Although he sometimes modified some of his statements or explanations according to the nature of the questions he had to deal with or the objections he had to face, the substance of his thought, on the essential point with which we are concerned in this study, has remained unchanged. Even reducing it to points of detail and vocabulary, one can hardly speak of an evolution, but only of complementary points of view, considered according to the occasion one after the other, and which all reappear at the end.

In q. 9, a. 2, on the subject of divine immutability, St. Thomas combines, as it were, the two explanations he had given in the Sentences and in the Contra Gentiles. God alone, he says, among all spirits, is immutable in the good, because he alone is his own end. All other incorporeal substances, being in power with respect to their end, have to make up their minds with respect to this end. They must inevitably make a choice, and this essential mutabilitas ad electionem, mutability allowing choice, entails for them the ineluctable possibility of passing from good to evil:

(Even in incorporeal substances) there remains a double mutability. The first, in that they are in potency in relation to their end; thus, there is in them a mutability according to the choice to pass from good to evil, as St. John Damascene says. The second, according to the place . . . Thus, there is in every creature a power to change. It relates either to their substantial being, as in the case of corruptible bodies; or to their local situation only, as in the case of celestial bodies; or to their final end and the application of their virtue to various objects, as in the case of angels.

In q. 83, a. 1, once again it is stated, in a brief but peremptory formula, that one cannot conceive of a created mind without free will: “For all that, man must possess free will by the mere fact that he is a reasonable being.” Now, St. Thomas clearly does not intend to speak of a free will that would only have to be exercised between “indifferent” goods, without any relation to the order of morality, outside the categories of good and evil. Such an invention does not seem to have even occurred to him here. It is in any case formally excluded by the immediate context of this article.

The first article of Question 63e is more important. As always, with the same clarity, St. Thomas first formulates, in terms very close to those of De Veritate, the absolute general principle from which he has never deviated. Everything that follows, it should be noted, is merely a clarification, a response to objections, that is to say, in the author’s mind, an establishment and defense, but not an attenuation of the principle:

Both the angel and any other reasonable creature are capable of sinning, if we consider them only in their nature; and every creature to whom it belongs not to be able to sin possesses this privilege by a gift of grace, not by the condition of its nature.

Then, as in the Sentences and De Malo, comes the fundamental reason. God alone is his own rule:

The reason for this is that to sin is nothing other than to deviate from the uprightness that an act should have, whether it be in natural acts, works of art, or moral matters. But the only act which is not lacking in uprightness is the one in which the rule is the very power to act . . . Now only the divine will is the rule of its own acts because it is not regulated by a higher end. Thus, the divine will is the only one in which there can be no sin; but in every will of the creature there can be sin according to the condition of its nature.

Once again, the objections must be answered. As in the Contra Gentiles and in the De Veritate, St. Thomas here rejects the analogy of the heavenly bodies. The latter are “indeclinable” as well as incorruptible, because they have only a “natural” operation, whereas in the angel, as in every spirit, above this “natural” action is the activity of free will, which is not without the risk of “inordination,” that is to say of sin:

The heavenly bodies have no operation but natural; and therefore, just as the evil of corruption could not exist in their nature, neither can there be in their natural action the evil of disorder. But above their natural action, there is in the angels the action of free will, according to which it happens that there is evil in them.

Finally, there remains the technical problem, which is no longer based on the ideal of spiritual perfection conceived crudely according to the ideal of the perfection of bodies, but on the fact of the perfection of the intelligence itself and of its perfection in a pure spirit. As much as St. Thomas has always been disdainful of the first—a disdain that is all the more remarkable since he does not scruple to evoke the incorruptibility of celestial bodies as a comparison—he has always taken the second seriously, trying to give an answer that would not be a simple refusal. He therefore concedes once more that the angel cannot be mistaken about its proper good, nor even, as man could in the state of innocence, cease to have a present attention to it. This good, therefore, is the object of its love, a natural and necessary love. By this very fact, seeing with equal clarity that its good comes to it entirely from God, the angel loves God not only necessarily, but with the same natural and ever-present love. How then could he turn away from it?

We shall answer, says St. Thomas, by distinguishing in this angel, as in every spirit, a double kind of love and a double relation to God. The angel naturally moves towards God, in so far as God is the author of its natural being, but not in so far as God is the object of its supernatural beatitude. The first of these two movements or loves is necessary: it is therefore always found in the angel or in man, as well, moreover, as in the animal or in the stone—though, of course, each being has it “in its own way,” or “according to its nature.” As the Quodlibetum primum says, “By nature, every creature loves God more than itself, each in its own way.” The spirit, even considered as nature, is not a simple “natural thing.” So, this natural love, which is not once again the fact of an illicit will (although it can be said to be illicit itself in so far as it is involved in every intellectual act), is nevertheless already, in the reasonable being, fully permeated with reason: “intellectual love, which is called dilection.” This is why St. Thomas does not want it to be “concupiscent love,” but already, in a certain sense, “love of friendship.” This is a love that is neither selfish nor truly disinterested, since it is once again the result of nature. But it is the natural love of a nature open to someone greater than itself. Love already more spiritual than animal, as William of Saint-Thierry said in the previous century. A disposition of a well-born soul—born of God. A kind of native generosity, founded on the instinct of the relativity and partiality of one’s own being. The first nobility of the spirit, already having a kind of half-morality, analogous in this to that power which, according to the Augustinian school, enabled the innocent man to stand upright (stare) without, however, being sufficient to make him move forward (pedem movere). This is a concrete definition of the “receptivity to grace” of which St. Thomas himself, like the Franciscan authors of his time, speaks on several occasions. As natural as it once again is, is it not already “an intermediary between the good by nature and the good by grace”? Nevertheless, it is once more a spontaneous love, “a natural inclination given to nature by God,” for which neither the angel nor man is properly responsible. Since it does not come from the free will and is never ratified by it, it cannot in the least be meritorious. The second movement, on the contrary, is “free.” It is of a different order. It is always free, and one can turn away from God by sinning:

(Third objection): What is natural is always present. Now it is natural for angels to be moved towards God by a movement of dilection. Therefore, this cannot be taken away from them. To the third objection it must be answered that it is natural for the angel to be moved towards God by a movement of dilection towards God according to the fact that God is the principle of its natural being. But that it turns to God as the object of its supernatural beatitude comes from a gratuitous love, from which it may have turned away in sin.

***

It can be seen that in substance the answer of the Contra Gentiles, taken up by the De Malo, is still there: it is in relation to its end (Contra Gentiles), in relation to supernatural goods (De Malo), in relation to the object of its beatitude (Summa), that the angel can sin. These three expressions are equivalent. The same doctrine will be expounded once again in the Compendium theologiae, where, as in the Contra Gentiles, the “proper good” and the “the sovereign good which is the last end” are contrasted in a similar way, or, as in the Summa, God “as the principle of all natural perfections” and God “as he is in himself.” St. Thomas remains true to himself, and through the diversity of points of view that he is led to consider in turn, his thought remains coherent. The distinction he proposes in the Summa between “the principle of natural being” and “the object of supernatural beatitude” corresponds, from an objective point of view, to the distinction that, from a more psychological point of view, is formulated, for example, in the De Malo between “natural” and “voluntary” goods. It also corresponds to the distinction which, mutatis mutandis [“all things being equal” (literally: changing what needs to be changed)], the Summa itself formulates elsewhere between “natural things” and “moral actions,” and once again between the “natural being” in relation to which the angel is always in act, and the “conversio” in relation to which he is first in power, and which can always occur “towards this or that goal.” On the one hand, what follows from nature as God has made it in each being; and on the other, the fruit of a voluntary activity, which is essentially free and which consists first of all in an option. On one side, a motus naturalist, [natural movement] necessary and inalienable, which subsists even in the damned; on the other side, going beyond nature, a amor gratuitus [gratuitous love], only meritorious, because in it alone morality is achieved:

To love God as the principle of all being belongs to natural love, but to love God as the object of beatitude is part of the gratuitous dilection of which merit consists.

Now, in the case of the pure spirit, who does not have to reconcile the elements of a mixed essence, this distinction overlaps exactly with another one, the same one developed in Contra Gentiles: a distinction between the spiritual nature considered purely in itself, abstractly so to speak and statically, and this same nature concretely related to its end, thus attaining its beatitude and entering into possession of the goods which exceed it, but for which it was made. In other words, to the two spheres of the natural or necessary and the free, voluntary, moral or “gratuitous,” in which the dual activity of the spiritual creature is respectively exercised, correspond to the two spheres of the “natural” and the “supernatural,” or, as others used to say, the datum and the donum. On the one hand, we have the creature as simply posited in being by its “Principle,” and on the other hand this same creature as related to its end and united to the “object” of its beatitude. If it cannot in any way break its natural link with its principle, it can, turning in on itself, refuse or deliberately neglect to relate to its object or its end. The rather psychological and subjective point of view of the preceding paragraph is joined by a more resolutely objective and ontological point of view, but the doctrine is in no way changed.

Moreover, in all this, the language of St. Thomas does not appear to offer anything particularly mysterious. It was, to a large extent, the language of his predecessors, as it was that of his contemporaries, and as it will once again be that of his immediate successors. Beyond the differences between the schools, which are considerable, and leaving aside certain nuances or intermediate concepts of lesser interest to the present subject of our study, the same fundamental opposition was formulated in almost equivalent terms everywhere in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It is based, if not upon the distinction formulated by St. John Damascene between Οέλησις/thélêsis [consent] and βούλησις/boulêsis [deliberate, determined will], then at least upon this distinction as it was then understood in the wake of Philip the Chancellor, and as St. Thomas himself understood it. St. Anselm had similarly distinguished “actio ex necessitate” or “actio naturalis” and “actio non necessaria” or “actio non naturalis,” and Duns Scotus said in the same way, without any originality: “There is a double appetite in the will, namely: a natural appetite and a free appetite,” or, “Being naturally active and being freely active are the first differences of the active principle.” From this resulted the opposition that a certain number of Fathers had formerly symbolized in the two words of image and divine likeness. On the one hand there was the fruit of the “natural will,” and on the other the fruit of the “elective or deliberative will, when the choice had been what it should be.” On one side, as Cassiodorus said, the “natural virtues of the soul,” on the other, the “moral virtues of the soul.” Such is the opposition that Geoffrey of Poitiers and many others put between voluntary or rational dilection and involuntary or natural dilection; that which William of Auxerre put between “natural love” and “gratuitous love” or between “works of nature” and “works of virtue,” etc. It is once again that of a Peter of Tarentaise, of a Roger Marston and of the whole Franciscan school between the “genus of nature” and the “genus of morals,” or, to speak like Saint Bonaventure, between the “order of nature” and the “order of justice,” between the “original justice” and the “Justice of merit.”

St. Thomas thinks and speaks here like all his contemporaries. There is, however, a new and important element in him, which a study of the historical significance of Thomism must highlight. This new element consists in the preponderant place that the words “above nature” and “supernatural” tend to take: an indication of the “physicalist” tendency of Thomism as opposed to the more “moralist” tendency of the traditional Augustinians. Hence, the correlative word “naturalis” becomes loaded with a certain equivocation: while continuing to designate a “physical” and necessary reality, i.e., a non-moral one, it is no longer formally opposed to the “moral” or “free.” The way will thus be opened to a new meaning, that of a reality that can already be moral although not supernatural, of a love that is already properly voluntary, that is to say truly free, although not “free” or meritorious. But this evolution is not yet complete. Moreover, this is mainly a question of emphasis. Once again, St. Thomas understands the opposition between “nature” and “supernature” within the same fundamental opposition of the necessary and the free, albeit in a modified perspective. In any case, there is nothing in him that foreshadows the distinction that a number of Thomistic theologians would later forge between “God as author of the natural order” and “God as author of the supernatural order,” or between “God as object of natural beatitude” and “God as object of supernatural beatitude”—as if natural beatitude, which in the case of man would have been obtained through an activity that still carries the risk of sin, should have resulted immediately, in the case of the angel, from an infallible, impeccable activity. The whole point, if one may say so, of the distinction made here by St. Thomas lies, on the contrary, in the opposition or crossing of the two words principium [principle] and objectum [object].

In other words, in the expression “beatitudo supernaturalis” which St. Thomas uses in the quoted text of the Summa and in some other places, the epithet “supenaturalis” is merely qualitative, it is not determinative. For St. Thomas, “beatitude,” without any other determination, is always supernatural and can only be supernatural. It is nothing other than the vision of God; it is obtained by the entry into possession of the “bona supernaturalia” of which the De Malo speaks. The essential word here is therefore the substantive: beatitudo. The proof of this is that in several other parallel texts it is used alone. Thus in 2a 2ae, q. 109, a. 1, ad 1m, where we find the contrast between God as “principle and end of the natural good” and God as “object of beatitude”; once again in the Quodlibetum primum a. 8, ad 1m, where the same contrast is formulated between God as “principle of all being” and God as “object of beatitude.” Never, on the contrary, does the same word “beatitude” recur in the two terms of the antithesis, determined once by “natural” and the second time by “supernatural.” There is never, either explicitly or implicitly, any allusion in the first antithesis, nor is there any question of any allusion to a “beatitudo naturalis,” that is to say, to some final end of the reasonable creature which would not be the vision of God and in relation to which, in another order of things, in another “hypothesis,” this creature would be impeccable. St. Thomas never sees in the created spirit, even as a simple supposition, a natural love of a voluntary and moral and at the same time necessary and infallible character, the object of which would be a God “Sovereign Good or Supreme Being of the philosophers” understood as the last end and beatitude of this spirit.

In the Summa or in the De Malo, as in the preceding works, there is no question of St. Thomas restricting the application of the absolute principle that he has just affirmed and established once again in its universality to a category of minds. No creature, according to him, escapes it. His doctrine may well be called a doctrine of “restricted sinfulness” or “relative impeccability,” in that he does not conceive of the angel as sinful in relation to all the objects and goods that present themselves to it, but only in relation to supernatural objects or goods, that is to say, only “by reason of the supernatural perspective of the option” that is offered to it. In the same sense, it can be said that he holds “with great firmness,” in the De Malo, “the view restricting the sinfulness of angels to the supernatural world alone.” It may well be noted, as noted above, that “from the Summa onwards St. Thomas resorts to the notion of the object of supernatural knowledge in order to explain how and to what extent error is possible to the angel,” error and consequently sin. This is certainly an effort on his part to “improve on previous explanations, and to make doctrinal progress.” But it does not affect his essential thesis. There is no need, we believe, to “conclude” that, “if the angel were not raised to a gratuitous destiny, if he had towards God only the relationship of creature to Creator, his natural love for that Creator would not be charity, but would render him impeccable,” or that if his destiny “had been proportionate to his nature,” he could not have had the presumption that made him fall through pride. Such “conclusions” are neither in accordance with nor contrary to the thought of St. Thomas: they are based on categories that are not his own. For him, as for the whole tradition that precedes him and as for a part of the tradition that follows him, a spirit cannot be content with its brute nature: it must come to its “conversio,” that is to say, to an option, and this option necessarily leads it to enter into the supernatural, or to exclude itself from it, since it is always made not in relation to some object “proportionate to its nature,” but in relation to God “such as He is in Himself.” So, when St. Thomas says, for example, that angels are impeccable in relation to natural goods, he is not saying that “in principle they are impeccable in their nature. He does not subscribe to “the thesis of the natural impeccability of angels.” It is going beyond his thought, or, to put it better, it is profoundly transforming it, to translate it by saying that he restricted “the peccability of angels to the supernatural hypothesis,” as if supernatural destiny were for him a “hypothesis” . . . This is to put oneself outside his perspective; it is to introduce, as an a priori principle of interpretation, a theory of double finality, a much later theory, which is not expressed either in the passages he devoted to this question of impeccability, or even anywhere else in his work. Consequently, we are condemned not only to understand several of his texts in the opposite way to their obvious meaning, but also to attribute to him a series of formal contradictions.

Therefore, far from restricting the principle of universal sinfulness, St. Thomas intends to strengthen it further, by renewing his points of view in order to answer an objection that he had encountered from the time of his commentary on the Sentences, which was not without its singular awkwardness for him, and against which, in virtue of the intellectualism that he had so widely adopted, he had to struggle to the end. By the consideration he introduces of supernatural goods, he wants to establish his principle in a more victorious way, by showing in a more precise manner how the power to sin exists in any rational creature. In this question of the possibility of sin, St. Thomas proceeds, it would seem, as in the question of the possibility of seeing God. This is first proved directly, by recourse to a general principle: the natural desire of the mind, which cannot be in vain. As to how this is possible, this will be dealt with afterward, and the objections that will inevitably arise will be resolved as best as one can; but supposing that these further explanations do not appear to be adequate in every respect and that a difficulty remains, the initial assertion would nevertheless remain, based as it is on a principle that leaves no room for doubt or exception.

Whatever the use that following theologians may have made of this or that of his formulae, based on presuppositions and problems that were not his own, whatever the legitimacy of the new distinctions and subtleties with which he “extended” his thought, the history of which could be instructive—a few features of which will be noted in the two chapters that follow—it must be recognized that St. Thomas maintains throughout his work, explicitly and without exception, the doctrine that he had received from tradition and that he possesses in common with all the Christian philosophy of his century. “As passionate as he was about ancient philosophy,” says Father Jacques de Blic, “St. Thomas was once again much more passionate about Christian tradition.” Here we have an example. This can be seen without yielding to any concordist temptation, without forgetting that in his psychology of the free act, as in his conceptions on the nature of freedom, the role of the will, the essence of beatitude, the kind of consistency of “nature,” etc., he shows himself to be resolutely and sometimes boldly innovative. This can also be seen, without denying the particular difficulties which resulted from some of these new positions—difficulties so serious that some historians are inclined to say they are insurmountable. One thing remains certain: for him, every mind is both free and sinful. Suarez was right to mention this: when St. Thomas treats the angel’s sinfulness, he does not only affirm it in this or that given hypothesis, but always his reasoning proceeds “quite simply the angelic nature considered in itself and in view of its natural imperfection.” In this at least, Suarez is a better historian and a better Thomist than several recent historians whose method is apparently infinitely more critical, and then several Thomists of today who advocate a return to St. Thomas beyond Suarez.

EDITORIAL NOTE: As far as we know, this (the third) chapter of de Lubac's Surnaturel (Book II) has not been previously translated. We wish to thank Maddison Reddie-Clifford—a doctoral student at the University of Notre Dame, Australia—for giving us permission to reprint his ongoing translation of this important book. Maddison specializes in the history of early twentieth=century Catholic theology and philosophy, notably Karl Rahner, Henri de Lubac, and Joseph Marèchal.