We find ourselves at the end of a most unusual year in education and I am reminded of a threat to the value proposition of schooling that educational philosopher Charles Bingham raised a decade ago in response to a technological era. Pointing to what he described as “momentous” changes in the availability of what could be easily accessed and learned online, Bingham declared that it had become “terribly easy to become educated.” Education, he noted, was “in a sense, everywhere.” Today, Bingham’s assertions seem hauntingly prescient in light of the pandemic and the proliferation of remote learning that has characterized the schooling experiences of children since March 2020.

Discussions about returning to in-person instruction throughout the past academic year have most obviously revolved around issues of health and safety. These discussions have also thrived on more invisible forces, namely assumptions about teaching and learning. One of these assumptions preventing the return to in-person instruction—particularly in places where teachers’ unions, more than viral infection rates, drove decisions to keep schools closed—is that, for students enrolled in a traditional school setting, the students’ education need not happen in the physical space of a school.

In other words, “school,” as we know it, can happen in any place, and even, as evidenced by the proliferation of asynchronous instruction, at any time. I specify students enrolled in a school because I do not wish to make this thought exercise an argument about the validity of homeschooling. Rather, I would like to consider what the assumptions about traditional in-school learning that have surfaced during the pandemic, and in particular Catholic education’s response to those assumptions, might advise for those invested in maintaining traditional schooling’s relevance in a post-pandemic world.

As a parent with children enrolled in Catholic schools, and as a faculty member at the University of Notre Dame’s Alliance for Catholic Education, I have paid close attention to the efforts Catholic schools have exerted to safeguard the option of in-person learning. Principals, teachers, and superintendents have overcome numerous hurdles, in the form of safety protocols, staggered schedules, and staff shortages to keep open their doors. In a few more extreme cases, parents and administrators have gone so far as to file lawsuits in states where governor mandates have prohibited the possibility of in-person learning.

Catholic education’s resistance to pressures to take in-person learning off the table is a curious one because it pushes back on the assumption I outlined above: that conventional schooling can happen in any place, at any time. In pushing back on this assumption, Catholic education poses implicit arguments about the nature of education that, while animated by tenets of the faith, might inform the work of educators across sectors. These arguments revolve around topics with implications for readers across educational sectors looking to keep education relevant in a post-pandemic world: the value of teachers, the nature of learning, and the potential parallels between schooling and living.

On Teachers and the Art of Teaching

When asked to recount one of the more exasperating moments of the pandemic, the majority of parents with school-aged children tend to cite spring of 2020, when e-learning transformed every kitchen in America into a makeshift classroom. The notion of parents teaching their children is not a new one, particularly within the sector of faith-based education. Pope Paul VI, in his Declaration on Christian Education, declared that parents are and ought to be the “primary educators” of children, thereby underscoring an alliance between home and school. Nevertheless, to claim that parents are the primary educators suggests that teachers and the act of teaching possess their own distinctive role—one that this pandemic has brought into sharp relief but also called into question.

The role of teacher and the subsequent act of teaching are so distinct, in fact, as to resist conflating them with the work that parents took on last March and that many parents of remote learners continue to experience today: facilitating learning. The pandemic has, in many ways, confirmed a trend in education—one that philosophers like Gert Biesta have referred to as the “learnification” of education: the tendency to couch everything in education in a language of learning. For the past several decades, school board meetings have revolved around analyses of “learning outcomes,” schools have been characterized as “learning environments,” students as “learners,” and teachers as “facilitators of learning.”

But if education is predominantly, if not exclusively about learning, then why have some schools endured the logistical and financial challenges of keeping their doors open for an in-person educational experience in this most unusual of years? Learning, after all, can be self-propelled, occurring anywhere and at any time (though that notion poses its own questions, which I will respond to momentarily). Consider, for example, the rise of the online, self-paced learning platform, Khan Academy, and the programs akin to Khan Academy that have proliferated in the wake of the pandemic.

While the shift to at-home learning has underscored the ubiquity of learning, it has also cast into sharp relief the first dimension of education I promised I would take up: the distinct gift of teachers and artful teaching. Between March 2020 and the present moment, the American public has certainly lamented learning attrition, but I have also heard students express their longing to be with teachers again. A group of second-graders in a Catholic school on the West Coast comes to mind in a particularly poignant way. Instead of “I want to be where the people are,” they sang, “I want to be where the teachers are,” in the opening line of a popular children’s movie song they remixed and performed over Zoom last spring.

Their sentiments echo those of teachers throughout the country with whom I work. Many have commented throughout this pandemic how much they miss teaching—even when they are purportedly “teaching” through electronic platforms in a remote context. These anecdotes, combined with many a Catholic school’s resistance to shutting down in-person instruction, suggest that while learning bears a necessary correlation to teaching, teaching involves more than the facilitation of learning.

One need only look as far back as last spring’s shutdown to substantiate this point. Despite teachers’ best efforts to keep a well-organized Google classroom page or to produce clear and concise video-recorded instruction, parents and guardians everywhere still let out sighs of exasperation. Many found themselves at a loss for what to do with Johnny’s struggles with reading or unable to explain to their children the “why” behind the lesson. Teachers have planned and evaluated as much as, if not more than, they ever have.

However, for many teachers denied the opportunity to teach in-person, there is no opportunity to exercise the practical wisdom necessary to know when a lesson on paragraph structure ought to give way, momentarily, to a lesson on syntax, or perhaps, in the moment that calls for it, a discussion about the point at which tolerance ceases to be a virtue. For a middle school Catholic school teacher, who experienced the shift from remote to in-person instruction in late fall, these moments of unscripted responsiveness are “gifts,” a reminder of “what it means to be a teacher,” for “We teach a lot beyond what we may expect.”

What follows from these observations is that teaching is more than the facilitation of learning, or “learning”—in and of itself—warrants reconsideration. I will attend to the latter momentarily, but in the meantime allow me to define teaching in a way that helps to explain why many Catholic schools have fought tooth and nail to keep their doors open. Teaching, unlike the mere facilitation of learning, transpires at the intersection of complex and always-shifting relationships between and among content, persons and purpose. To that end, there can be no script for teaching, which demands sound judgment and deep knowledge of subject area, of persons being taught, and vision for why education matters—the latter of which are often, if not always, subject to variation.

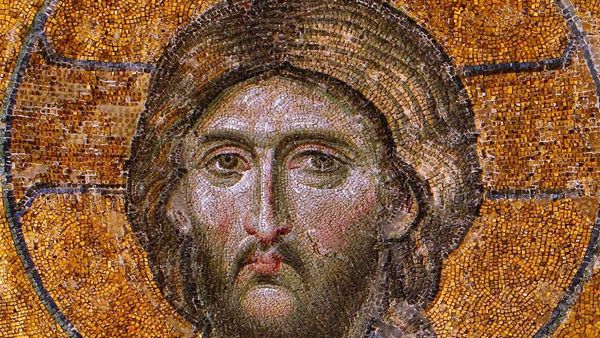

I cannot help but think for a moment about the miracle of the wedding at Cana. How fitting that, in this moment that marked the beginning of Christ’s public ministry as teacher, his deep connection with the person of Mary standing before him, combined with a keen understanding of the telos of his ministry, inspired him to deviate from the scripted curriculum (“My hour has not yet come”) and to produce precisely that which was needed in the moment. In that moment, Christ both began and sealed his identity as Christ the teacher. The upsurge in remote learning suggests the degree to which this pandemic has eroded society’s appreciation for the deeply relational work of teaching that is simultaneous anticipatory and responsive in its orientation. The education sector would do well to focus not only on lost learning, but to give deep consideration as well to lost teaching as the nation seeks to right the educational ship.

On Learning

Along with the “learnification” of education has come an emphasis on the more cerebral, rational domains of learning, sometimes at the expense of the more visceral and embodied experiences that can constitute learning. One of the difficulties teachers experience in dual mode or virtual classrooms in their ongoing quest to ensure that students are taught as well as possible, is their limited ability to read the body language of students entrusted to their care. Consider, for example, a group of students struggling to make sense of the chemistry behind the scientific phenomenon of water’s freezing point.

Some of the most telling signs of struggle among this group of students—silence and glazed-over expressions—are difficult, if not impossible, to grasp when students are muted or not visible on the screen. Part of the resistance of Catholic schools to the pressures to keep schools closed for in-person instruction into the 2020-2021 academic year stems from the incarnational dimensions of the Catholic faith. The entire Christian narrative is premised on the fact that God, in his all-powerful, all-knowing divinity, allowed his only Son to take on the flesh and enter into a world of human, material things. Even the Hebrew name for Christ, Emmanuel, confirms this reality in light of its translation: “God is with us.”

Some of the most powerful ways of intervening in students’ conceptual struggles hinge on walking with students, on knowing them, not only as learners, but as persons. One of the best explanations of freezing point depression I have encountered, and one that resolves the conceptual struggle outlined above, grew out of a teacher’s knowledge of her student’s family life.

Knowing the student came from a large family and having heard the student groan about his younger siblings’ tendency to mess up his room, the teacher compared the addition of substances to water to the addition of toys and bodies to a room. The more toys and bodies, the more difficult the task of organizing. In the same way, the more substance one adds to water, the greater challenge water molecules face in organizing themselves into the hexagonal crystal formations that exist in a frozen state. It is the origin of this analogy, more than the analogy itself that interests me. After all, this anecdote, and the teacher’s knowledge of her student’s storied life that produced it, suggests that the fully embodied lives of students matter in the context of learning.

The previous anecdote, much like the previous discussion on teaching, posits another truth about education with important insights into learning: Students, when gifted with an experience of personal encounter, will learn more than what a school’s curriculum professes to teach. This principle of learning is perhaps best explained by yet another moment I witnessed in a Catholic school just prior to the pandemic. The first-grade teacher, who had a morning ritual of shaking hands and greeting each student by name, was met by a snarky note of criticism by one young man who had opinions about the teacher’s new haircut. The teacher, crouching to meet the student at eye level, very calmly repeated the words back to him, asking if he would like to alter his greeting, as those words, she noted, did not sound like his.

The child’s eyes dropped to the ground and then returned to the teacher’s as he rephrased his comment in a manner more consistent with the standards of human dignity. Perhaps one way of conceptualizing schooling is to imagine a community of individuals holding up lights for one another—lights that call us out of ourselves to make us more fully ourselves—lights that illuminate our flaws and shortcomings but that also show us the promise of who we can most fully become. Both the communal and the incarnational dynamics that are part and parcel of what it means to be a Catholic school have, throughout the past year, begged for a version of learning that begins from and begets personal encounter.

The Purpose of Education

The topic of learning itself gives way to the question of education’s overarching purpose. In reflecting on the dynamics of education throughout the past year, I have come to see how it is possible to interpret families’ and school leaders’ insistence on in-person learning as an implicit argument about the overarching purpose of education. In the impassioned arguments of those committed to keeping the doors of schools open is an argument that schooling, more than an education in how to read, to count, to advance, or to prepare for one’s career, is an education in how to live. And human life, as C.S. Lewis reminds us has “always been lived on the edge of a precipice.” To continue forward with education in the fullest sense possible carries with it a lesson of its own for students and all those involved in their formation: that life has never been normal, that there are always rivals that antagonize our work. Bottom line: “We must do the best we can.”

In the ministry of Catholic education, full human flourishing, always and necessarily in deep communion with the life of Christ, is considered education’s end game. If preparation for a life both with and in Christ is the desired outcome of education in this frame, then we need look no further than scripture to see why many Catholic schools have exerted endless amounts of energy to keep open their doors. The Holy Spirit did not enter the locked doors of the upper room where the disciples were fearfully hidden when the conditions were perfect. In fact, by all measures—of turmoil, stress, anxiety, and safety—there could not have been a worse time for that Pentecostal moment. Nonetheless, though, the doors were thrust open, the apostles emerged, and out of a state of utter uncertainty, instability, and brokenness, the first acts of the apostles—and hence the Church—was born.

As I reflect on what, to some, may seem a radical orientation in the overarching purpose of Catholic education, I am struck once more by the observations of Charles Bingham, whose reflections on education earlier this century, seem eerily aligned with the landscape of K-12 education this past academic year. Bingham’s conclusion in 2011, in response to the ubiquity of education, was that “Unfortunately, education’s everywhere-ness has not yet become a general cause for rethinking educational ideas. Educational ideas have tended to remain the same up until now.”

As schools prepare for a new academic year in what we hope to classify as a post-pandemic world, they will find themselves grappling with what the recent span of remote instruction has done to teaching, learning, and the overarching purposes of education. If hope springs eternal, may that hope be this: first, that educational ideas not remain stagnant, or—far worse—continue to narrow more than they already have within the past year. And finally, that the different tenors, textures, and telos of Catholic education may serve as a reminder that the field of education, much like a body of students questing to learn, finds itself most likely to flourish in dialogue and—dare I say at a moment when safe distance is still the norm—in communion with others.