Is the modern administrative state illegitimate? Unconstitutional? Unaccountable? Dangerous? Intolerable? American public law has long been riven by persistent, serious conflict, even a kind of low-grade cold war, over these questions.

Critics of the administrative state argue that constitutional and administrative law have come to license an administrative apparatus wielding executive powers of frightening scope and power. According to the critics, these developments threaten to undo the original constitutional structure, intrude on private ordering and economic liberties, and produce unaccountable and undemocratic policymaking. The critics make three separate points.

First: Broad grants of authority to agencies amount to an unconstitutional transfer of legislative power to the executive. In defiance of Article I, Section 1 of the US Constitution, agencies now exercise that power. Second: Some of the most powerful agencies are independent of the president, and so represent an invalid encroachment on the executive power. In defiance of Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution, these agencies exercise executive power free from presidential control. Third: The modern rule of judicial deference to agencies on questions of law is an encroachment on the judicial power, or perhaps an abdication of the judges’ obligation to say what the law is. In defiance of Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution, agencies are allowed to interpret the law.

In the critics’ view, then, the administrative state manages a neat trick. All at once, it violates the original constitutional allocations for the vesting of legislative, executive, and judicial powers.

The critics are no monolith; with respect to particular issues, they combine in shifting coalitions. Some of them are originalists; they aim to speak on behalf of what they see as the original meaning of the Constitution. Others are libertarian; they are focused on liberty, as they understand it, and they think that modern administrators endanger it. Still others are democratic; they are concerned with accountability and democratic control. There are important differences among these perspectives (and in different variations, they can be found in many nations). But they converge, above all, on one major concern: that the administrative state threatens the rule of law.

To originalists, the administrative state is a patent betrayal of the commitments of the original constitutional scheme and the system of separated and divided powers. To libertarians, agencies possess largely unchecked discretion that allows them to wield arbitrary power, intruding on private liberty and private property and acting in violation of core rule-of-law values. To democrats, the chain of accountability from We the People to officials wielding state power is simply too weak; it is undermined by grants of excessive agency discretion, which allow legislators to duck political responsibility for ultimate policy choices.

Of course these concerns can be mixed and matched in all sorts of ways. Originalists may say that the Constitution, rightly understood, creates a chain of democratic accountability, libertarians may say that the original Constitution was libertarian, and so on. In any case, the very existence of the contemporary administrative state is said to create some kind of crisis of legitimacy.

Supporters of the administrative state, although highly diverse in their approaches and emphases, reject the idea that it is in some wholesale way politically or legally illegitimate, whatever local problems and pathologies it doubtless displays. They think that it is essential to promoting the common good in contemporary society; that it does far more good than harm; that it is a clear reflection of democratic will; and that it is entirely legitimate on constitutional grounds. In short, they welcome it. Sometimes they urge that far from being constitutionally forbidden, the administrative state is constitutionally mandatory, in the service of the general welfare.

Pointing to early practice in the American republic, the supporters emphasize what they see as the weakness of the originalist arguments against the administrative state. They deny that it violates the original meaning of the Constitution. They insist that nothing in Article I, Article II, or Article III is inconsistent with the general operation of modern administrative agencies. They point to the constitutional legitimacy of the administrative state as embodied invalid congressional authorizations (which, after all, created the Department of Transportation, the National Labor Relations Board, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the rest). Some of them contend that originalism is not the proper approach to constitutional interpretation. They add that it would be arrogant, a form of hubris, to reject many decades of settled understandings, even if those understandings did turn out to run up against widely held views in the 1780s and 1790s.

Some supporters of the administrative state also underscore its democratic accountability, mediated through both Congress and the presidency in different ways. They note that Congress, which is democratically accountable, is subject to the citizenry, even if it grants broad discretion to administrative agencies. If Congress does that, perhaps that is exactly what the citizenry wants it to do. If so, what is the democratic problem? Recall that all of the major agencies are creations of Congress. In any case, many of the most important agencies, including the cabinet departments, are run by people who serve at the pleasure of the president, and so are in that sense highly accountable to him.

To be sure, some agencies are “independent” of the president, in the sense that their members can be fired only for cause. This is true of the Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Reserve Board, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. But the independent agencies are not all that independent. Their chairs are appointed by the president, after all, and most of the time, their policy preferences are broadly in line with the White House. Even if the president cannot order these appointees to make particular decisions, the power of appointment, together with other authorities, ensures that they are anything but a “headless fourth branch” of government.

Finally, supporters defend the administrative state as embodying a reasonable set of judgments about the common good and the general welfare. Indeed, they say that the administrative state is, in some form or other, essential to protecting the liberty and welfare of many people who would otherwise be hurt or subordinated by market exploitation or unjust terms of employment, or harmed by the vagaries of ill health, poverty, pollution, and old age. They argue that much of administrative activity is a response to market failures, as when polluters are able to avoid paying for the problems they cause. They also contend that administrators respond to an absence of information (on the part of, say, employees, consumers, and investors) and to unfair background conditions, deprivation, and unfairness.

In these ways, those who support the administrative state deny that it is a threat to liberty, properly understood. Consider some of the actual activities of that state. Would people be freer without child labor laws? Without occupational safety laws? Without food safety laws? Without protection from sexual harassment? Without air pollution laws? Without protection against pandemics? Some defenders of the administrative state argue that it is not only constitutionally permissible, but also in some sense mandatory, if the goal is to carry into execution the promises of the constitutional scheme.

Separately and together, we have argued for our own, first-order views on these matters, which distinctly incline toward broad discretion for the administrative state. One of us (Sunstein) has argued that this broad discretion should be subject to welfarist principles, ensuring a focus on human consequences and employing cost-benefit analysis. The other (Vermeule) is not enthusiastic about cost-benefit analysis, while agreeing that promotion of the common good and human well-being, broadly understood, are the proper ends of government. But neither of us believes that the status quo is perfect; we might favor quite significant reforms, while not always agreeing on the forms they should take.

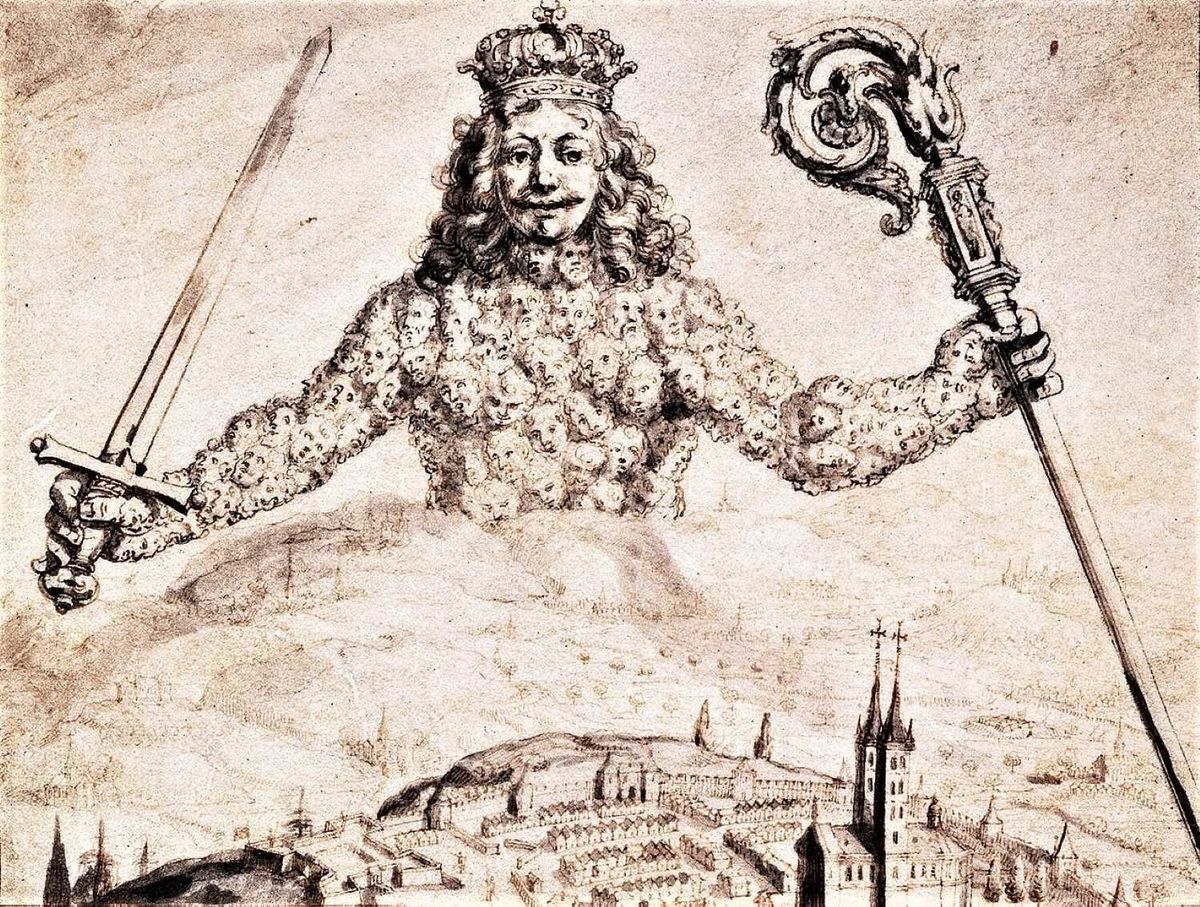

Our project in Law and Leviathan, however, is definitely not to repeat and insist upon our first-order views, although we just as definitely do not mean to abandon them. The goal is simultaneously more modest and more ambitious. We hope to understand and address the concerns of the critics from the inside, offering a structure that can transcend the current debates and provide a unifying framework for accommodating a variety of first-order views, with an eye to promoting the common good and helping to identify a path forward amid intense disagreements on fundamental issues. In our view, this framework can be embraced not only by ambivalent or uncertain observers attempting to make sense of fundamental questions, but also by the most enthusiastic supporters of the administrative state (even if they would prefer fewer constraints, in their ideal world) and by the most committed skeptics (even if they would prefer constitutional invalidation, in their ideal world). We acknowledge that this hope is highly optimistic. We nonetheless believe that it is realistic and we shall offer some evidence in Law and Leviathan in support of that belief.

As analogies, consider enduring legal and political frameworks such as the US Constitution, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the Nicene Creed, all of which have allowed wide scope for contest and conflict within a common order. Our framework is meant as an effort to draw on, and embrace, what we see as the strongest arguments on various sides, emphatically including those of the most vigorous advocates of the administrative state, and also the most severe skeptics about it. We acknowledge that those skeptics may not agree with our claims about what is strongest in their positions.

In Law and Leviathan, we carefully assess claims about the legitimacy of the administrative state made by both these supporters and skeptics. As in the 1930s, so in the first decades of the twenty-first century: The exercise of broad discretionary authority by the administrative state is under fundamental assault, not only in the political process but also as a matter of constitutional law. In our view, engagement with particular agencies, and particular practices, greatly weakens the force of that assault. Consider the cabinet agencies, including not only the Departments of Defense and State, but also the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Transportation, Energy, and Health and Human Services, along with the Environmental Protection Agency. All of these have been created by Congress. In many cases, Congress has sharply limited their discretion. In all cases, they are subject to the ongoing control of the president.

Or consider the independent agencies, including the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the Social Security Administration, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. All of these are also creations of Congress. Much of the time, their discretion is also sharply limited. And while they are not subject to the ongoing control of the president, their members are appointed by him. Their policies tend to fit with his inclinations.

Simply as a matter of history, it is not easy to demonstrate that the modern administrative state transgresses lines drawn by the original Constitution, whether in Article I, Article II, or Article III. Some of the most prominent claims of transgression turn out to be exercises in rhetoric, not history. Even if those claims could be defended, many people are not “originalists.” They agree, of course, that the text of the Constitution is binding, but they do not agree that its meaning is settled by what people thought in 1787.

If we are concerned with democracy, freedom, or the general welfare, there is a great deal to be said for, not against, the modern administrative state. In contemporary government, federal and state agencies are arguably products of democratic will (acknowledging the role of self-interested private groups). In some cases, they promote freedom, at least on certain specifications of that contested ideal. They can and often do promote the common good and increase human welfare. Many people do not love cost-benefit analysis, but if we care about welfare, it is at least noteworthy that the benefits of agency action often exceed the costs, and by a large margin.

We acknowledge that some agency practices do raise serious constitutional questions, and we are keenly aware that many people will find the picture we have just drawn to be far too rosy. This is far from the best of all possible worlds. Sometimes agencies violate the law. Sometimes they act arbitrarily. They can be unfair. They can be influenced by powerful private interests; they might even do their bidding. They might not use their expertise. They can threaten liberty. They can reduce welfare and act in ways contrary to the common good.

Our central claim here has been that, at its best, American administrative law has its own internal morality, a reflection of the internal morality of law. That internal morality embraces many of the concerns and objections of those who are deeply skeptical of the administrative state. It empowers but also channels administrative authority, not by abolishing agencies but by insisting on a set of principles that might fairly be said to constitute the old ideal of the rule of law as a rational order that helps to promote the common good. It offers surrogate safeguards—not constitutional invalidation, but checks and limits that promote fidelity to law and that call for reasoned justifications. Crucially, these both shape and legitimate the administrative state, helping to make agency action efficacious not as arbitrary command but as law.

This is one of the oldest ideas in law and legal theory, particularly the law of executive power. In the thirteenth century, Bracton’s treatise on the laws of England observed something very similar of the king—in terms that, for all we know, may have influenced Fuller’s account. “[B]ecause law makes the king,” Bracton (or an interpolation to Bracton) said, “let him therefore bestow upon the law what the law bestows upon him, namely, rule and power. [For] there is no rex where will rules rather than lex.” The point here is not best understood in terms of constraints on the king, although that corollary can be drawn. Rather, the point is that law is constitutive of the place and office of “the king,” and that ruling according to law is itself a precondition for the efficacy of rule as king. This, appropriately transposed and modified, is our basic claim about the morality of administrative law. Its procedural principles both constitute and channel administrative action, making it efficacious as law. The result is Janus-faced: the principles of administrative law’s morality both empower and constrain the administrative state. It is precisely this duality that makes us hopeful that these principles can serve the basic aim of administrative law of settling “long-continued and hard-fought contentions, and enact[ing] a formula upon which opposing social and political forces have come to rest.”

In our view, the morality of administrative law is something to celebrate. To the extent that the United States lives by it, it is something for which Americans should be grateful. And even in its modest forms, it has critical bite. It suggests reform, not only celebration. In multiple domains, and all over the world, we need more fidelity to it.

EDITORIAL NOTE: Copyright © 2020 Law and Leviathan by Cass R. Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule. Used by permission of Harvard University Press. All rights reserved.