The circumstances of a life under lockdown, in its utter solitude, monotony, and vulnerability, are radical; for most, these circumstances are also radically new. For one population, however, life may have changed very little since the outbreak: members of monastic communities. Though monasteries have closed their doors to visitors, monks and nuns are continuing their ordinary rhythm of work and prayer, ceaselessly interceding on behalf of the ill and suffering.

The COVID-19 lockdown is not my first immersion in radically simple, stable life. I spent last summer living and working with Benedictine nuns at the Abbey of Saint Walburga in Colorado. Since that time, I have continued to reflect on Benedictine spirituality daily as I translate a biography of Saint Benedict into English. Now, the outbreak has thrust me back into the practices and patterns that I cultivated at Walburga, unexpectedly transforming what seemed to be a barren desert into a source of life.

Those who are not on the front line, and whose lives have slowed and been simplified during the outbreak, would do well to look to monasticism for guidance at this time. Although few of us are called to monastic life, all of us are called to enter into the circumstances before us today; life under lockdown is an opportunity we do not want to miss, for monastic practices can benefit our spirits and bodies alike. Guided by Saint Benedict, our loneliness can give way to prayer, we can obediently welcome restrictions as an opportunity for stability, and we can experience freedom in the midst of an apparently monotonous rhythm of life.

From Loneliness to Prayer

A life under lockdown is pervaded with silence, in striking contrast to the noise that typically fills our commutes and our offices. Stripped of this “soundtrack of our everyday routine,”[1] we may seek refuge in the comfort of endless digital conversations or constantly updating news feeds, which serve to narcotize our loneliness.

Yet, this need not be the case. When the human person moves beyond fear to embrace silence, she flourishes on every level of her being. Biologically, constant auditory input can overstimulate the brain, interfering with its function, while silence leads to the birth of new neurons in brain regions responsible for learning and memory.[2] Excessive noise can provoke a restless anxiety, while silence attenuates stress through lowering levels of cortisol and adrenaline.[3]

Our minds are often inundated by the noise of dreams, worries, and images, a restless churning that stifles our inner life. Only in silence can we “listen carefully,” as St. Benedict writes in the Prologue to the Rule, “to the master’s instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart.” For silence is not merely the absence of stimuli, as the modern mindfulness movement may presume. Rather, silence is the manifestation of a presence, the turn to the presence of the Lord who has been present all along, as Mark Salzman beautifully describes in his novel Lying Awake:

Loneliness, the hole in the center of her being.

Look at me, answer me, Lord my God!

The response came in the form of understanding, and it came all at once, as if a dam had burst in her soul. Her search for God had been like a hand trying to grasp itself. God, who is infinite, cannot become present because He can never become absent.

In the recognition of his presence, therefore, silence becomes prayer. At this time, many Catholics are deprived of the sacraments, particularly the sacrifice of the Mass, but the Lord remains present in scripture and in his Church, and continues to invite us to enter into the rich Christian contemplative tradition.

While most neuroscientific explorations of contemplative practices are plagued by serious limitations, including ambiguous definitions and categorical errors, several brain imaging studies provide possible windows into the neurobiological correlates of prayer. For instance, prayer seems to activate brain regions that are implicated in theory of mind, which is the ability to grasp another’s perspective, and the default mode network, which may underlie cognitive self-understanding.[4] More broadly, prayer appears to shift neuronal activity from the lower brain, where emotions and physical functions are regulated, toward areas of the frontal cortex involved in reasoning and empathy. These shifts in neural activity support an active, relational conception of prayer.

Though hidden and solitary, prayer is no passive escape from life: it is face-to-face dialogue with the living God, the highest and most creative of activity.[5] Furthermore, prayer is not individualistic, but an act of begging on behalf of the whole world that his Kingdom might come. The center of Benedictine life is the prayer of the Divine Office, in which a person receives the words of the Psalms (and her true self in them) and offers them back to God for the sake of the Church, just as Christ did. The Office punctuates the day and night of the monk, leading him to prayer when other members of the Body of Christ may be working or sleeping, and perhaps neglectful of the Lord who sustains them in being.

At this time, when Christians throughout the world are praying for an end to the pandemic and the comfort of those who are suffering and dying, the communal dimension of prayer is particularly evident. Such prayer demands a confrontation not only with the suffering of others, but with one’s own mortality: as the Psalmist writes, “Our span is seventy years / or eighty for those who are strong / And most of these are emptiness and pain / They pass swiftly and we are gone” (Psalm 90:10). Death, however, no longer provokes fear in the Christian, for as the Exultet proclaims on Easter night, “Christ broke the prison-bars of death and rose victorious from the underworld.” The practice of remembering one’s death has well-established psychological benefits,[6] and in fact the Psalmist goes on to ask the Lord to “Make us know the shortness of our life / that we may gain wisdom of heart” (Psalm 90:12). The individual practice of memento mori lifts a person’s gaze the horizon of eternity, while prayer unites that person to others who are suffering, transcending the apparent solitude of social distancing and infrequent or spiritual Eucharistic reception.

The end of monastic life, even outside the formal times of the Divine Office, is prayer without ceasing (1 Thess. 5:17). The Lord is present in the most ordinary circumstances of daily life; indeed, “the world is charged with the grandeur of God.”[7] Silence—the recognition of his presence—can fill even banal experiences with what St. Benedict describes as “the inexpressible delight of love.” As Helen says of Sister Pricilla in Lying Awake:

And her actions were all beautiful. She turned even the most ordinary tasks, like pulling maps down or emptying the pencil sharpener, into sacraments. On the other hand, she could talk about faith in a way that made it sound like common sense. She made divine things seem human, and human things seem divine.

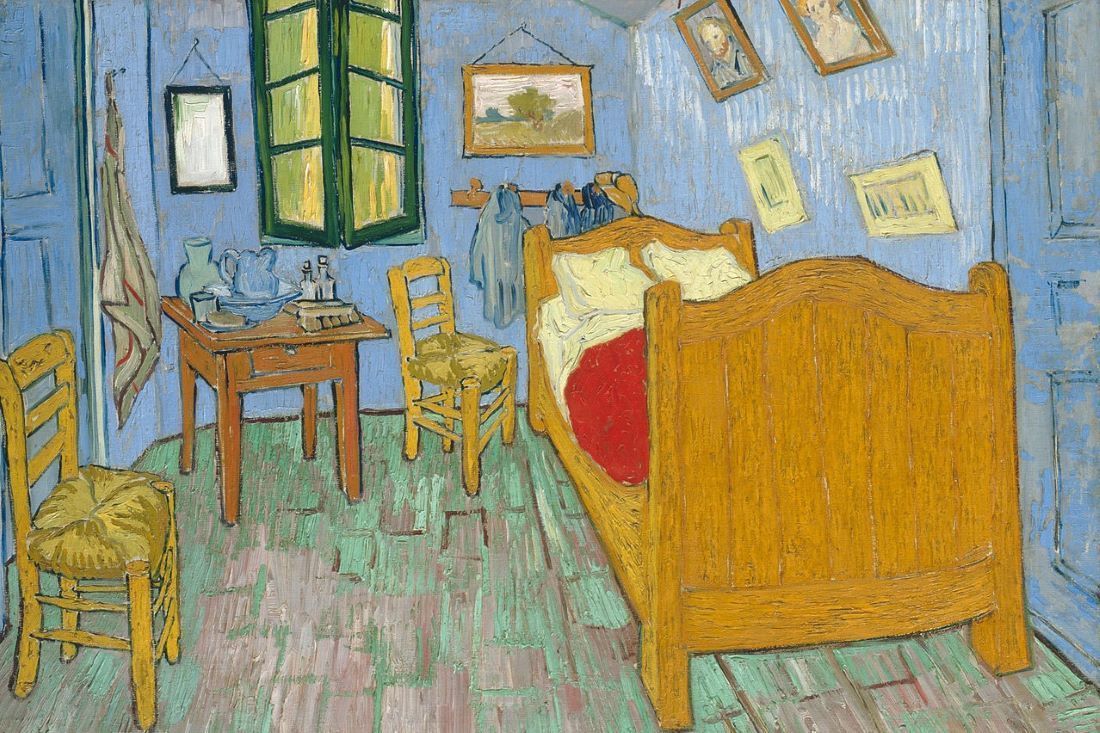

One who bears the memory of the encounter with God cannot help but recognize reality as a gift, and so experience wonder and reverence before all things. In the Rule, St. Benedict exhorts his monks to “regard all the vessels of the monastery and all its substance, as if they were sacred vessels of the altar.” Through the turn to the present moment, and the recognition of the One who fills it with His presence, prayer elevates daily life into something sublime. In the words of Etty Hillesum:

And now, now that every minute is so full, so chock-full of life and experience and struggle and victory and defeat, and more struggle and sometimes peace, now I no longer think of the future . . . I live here and now, this minute, this day, to the full, and life is worth living. And if I knew that I was going to die tomorrow, then I would say: it's a great shame, but it's been good while it lasted.

Thus, we can choose to live under lockdown as the disciples did after the Ascension of Christ. Though they, too, were locked indoors and likely afraid, the apostles and holy women “devoted themselves with one accord to prayer,” and so were prepared to receive the gift of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost (Acts 1:14, 2:1-4). Our own solitude will be similarly transformed if we remain vigilant in prayer, listening in the silence for the still, small voice of the Lord.

From Restriction to Stability

In the midst of a global pandemic, travel is a danger that should be limited. Although the modern mentality may eschew stability as the lot of the unsuccessful, St. Benedict wholly embraced stability. Along with the three vows of the evangelical counsels (poverty, chastity, and obedience) Benedictines take a fourth vow to remain within a particular monastery, which could be justified by Meister Eckhart with the pithy line: “God is not elsewhere.”

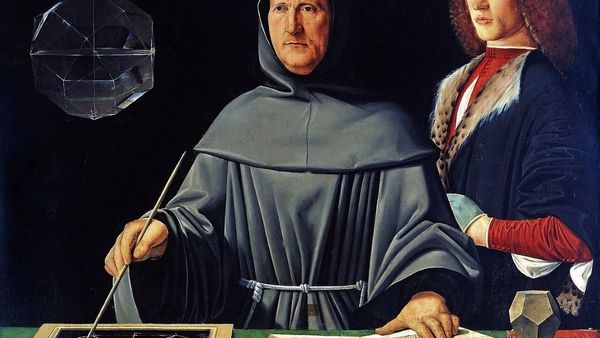

The vow of stability addresses one of the defining characteristics of human life: its systemic unpredictability. Constant external volatility—as Benedict observed during his years of student life in Rome—leads to internal chaos, a spark that easily ignites the “tinder for sin” (CCC §1264). In part, this is because unpredictability inhibits the formation of habits; in biological terms, predictability is necessary for the brain to develop a new skill, because repetitive practice generates the patterns of activation that consolidate neural circuits. As Donald Hebb summarily explains: “neurons that fire together wire together.” Travel and moving homes disrupt habits and exacerbate unpredictability, while stability nurtures habits in a predictable exterior environment. As virtue itself is a habit, defined by the Angelic Doctor as habitus operativus bonus, stability disposes the mind and soul to cooperate with the gradual but transformative work of the grace of God.

But the Benedictine vow of stability goes beyond ensuring the predictability of daily life: it joins a nun more closely and freely to her sisters in community. A monastic community is united by a common call and a common desire to be obedient to that call. The Rule cultivates this unity materially, as members share all things in common that they might be of “one heart and mind” (Acts 4:32), and relationally, as monks are taught to treat one another with compassion and respect, and indeed to welcome one another as Christ.

But Benedictine monks do not enter into community for the sake of community but only for the sake of love, who is God. When they gather for the Office, the highest act of the “school of the Lord’s service,” the monks face each other in two monastic choirs, listening and praying attentively as they chant the alternating words of the Psalms. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer explains in Life Together, Christian community is not “an ideal which we must realize; it is rather a reality created by God in Christ, in which we may participate.”

All people are called to a life in community. Each human person is created in the image of a Trinitarian God, and therefore made for a relationship of love with an irreducible Other. In the language of Martin Buber, the I can only become itself by transcending itself, by entering into communion with others, Thou, and ultimately with God, the Eternal Thou.

God calls most Christians to communion in the setting of family life. In the domestic Church, as in the monastery, Christians are to love and serve another for God’s sake. And, as with monastic life, intimate family life dispels any romantic notions of love. In the midst of the mundane and challenging circumstances of reality, the family continually discovers the truth of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s remark in The Brothers Karamazov: “Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing compared to love in dreams.” In such close quarters, conflict is inevitable and failings are apparent; the love of a family demands forgiveness, invites vulnerability, and requires patience. Yet through their human love, the family remains an image of the divine, an instrument of the grace of God by which each member is educated in charity and virtue.

The stability of family life not only forms the souls, but the body and brain of the human person. From the time an infant is in the womb, reciprocal interactions between a mother and her child provide essential environmental cues that shape her development.[8] Through shared gaze and emotions, touch and conversation, the love of family members strengthens the architecture of a child’s developing brain.[9] Indeed, throughout the lifespan, brain-to-brain coordination with loved ones leads to biological flourishing: it regulates hormone levels, enhances immune function, balances neurotransmitter levels, and facilitates learning and growth. Social bonds provide experiences of connection and meaning, and in the final stages of life, embeddedness in close relationships is the greatest determinant of one’s resilience.[10] The human person is an inescapably relational being.

In the face of widespread restrictions on our movement and behavior, and even our worship, we are more deeply aware than ever of the truth of Luigi Giussani’s claim: “The condition for being true in a relationship is sacrifice.” Stability always requires the sacrifice of obedience. In Benedictine life, monks take a vow of obedience, and are educated to obey their superiors as they would Christ himself. Even when confronted with impossible tasks, the monk is to eagerly abandon his own will out of love and trust in the Lord’s help in his weakness.

From obedience, then, spring the other two evangelical counsels: having renounced his own will, a monk renounces ownership and control over his possessions through the vow of poverty, and renounces his desire for the exclusive love of another person through the vow of chastity. By virtue of her Baptism, each Christian receives new life in Christ, the poor, chaste, and obedient one, and so we must work for detachment from our own will, our wealth, and our pleasure. Through obeying our families and leaders, we learn to embrace sacrifice as the path to our fulfillment, for the horizon of obedience to our circumstances is obedience to the will of God.

This is not to characterize the Christian life as automatic or passive. Rather, the free act of obedience creates a space of receptivity in the heart in which one can learn to recognize the event of the Incarnation. As the unnamed protagonist of George Bernanos’s The Diary of a Country Priest expresses it, “The unforeseen is never negligible . . . For the Master whom we serve not only judges our life, but shares it, takes it upon Himself. It would be far easier to satisfy a geometrical and moralistic God.” Our Lord is not moralistic; he is love Incarnate. Through embracing sacrifice in the unique circumstances of own life, we discover his very presence within it.

From Monotony to Freedom

Life under lockdown is simple and repetitive; one day after another unfolds along a similar pattern of work, prayer, and rest. For those who have been conditioned to understand freedom as a wide range of available choices, this rhythm is a source of profound discomfort, often provoking an endless litany of complaints or a helpless grasp at measurable productivity.

Yet this repetitive rhythm of life is highly consonant with the biology of the human person. The systems of the body are governed by a neurobiological clock, a cluster of tens of thousands of cells in the hypothalamus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Depending on the time of day, the suprachiasmatic nucleus releases varying amounts of hormones to the rest of the body, thereby coordinating the proper timing of functions such as metabolism and wakefulness. Each day, the internal clock is reset by the cycle of sunlight, maintaining the length of the circadian rhythm at 24 hours. Disruption of the rhythm (through jet lag, for instance, or working through the night) can severely impair physical and mental health. Furthermore, sociological fieldwork has established that our awareness of God appears to follow a similar daily rhythm, peaking in the late morning, declining through the afternoon, and rising again by the end of the day.[11]

Hence, as Alasdair MacIntyre writes in After Virtue, regular daily structure is an essential precondition for a meaningful life, because it enables one to carry out long-term plans and projects. In Benedictine life, those connecting “threads of large-scale intention”[12] are not plans chosen by the individual, but those chosen by God and enacted through obedience to the Rule. As Helen learns in Lying Awake:

The rigorous daily schedule, which seemed to allow for no personal freedom, taught her to measure freedom differently. In religious life, everything was turned either upside down or inside out: to gain, one had to lose everything first. The only path to victory was through surrender. To become full, one had to become empty.

Monastic life is indeed rigorous. However, Saint Benedict insists that he wrote his “little rule” for beginners, and that its counsels are neither harsh nor burdensome. The voice of the Rule is one of discretion, allowing for individual differences and accounting for weakness. For instance, the Abbot is permitted to provide occasional indulgences at the dinner table, including a daily glass of wine because monks “cannot be convinced” to embrace total abstinence. Through these concessions, Saint Benedict invites his monks to a deeper humility, for one can only ascend the ladder of humility by the grace of God. A daily rhythm, the following of a Rule, merely makes the soul available for the work of the Holy Spirit.

The cornerstone of the Rule again is the Divine Office, the prayer that “sanctifies the day and all human activity,” in the words of Canticum Laudis. These precisely timed moments of prayer cyclically punctuate the day of a monk or nun, orienting their biological rhythms to the praise of the Lord who is present in all. As Mother Celine explains in Ron Hansen’s Mariette in Ecstasy:

We seem to mystify people who are slaves to their pleasures . . . our food is plain, our days are without variety, we have no possessions nor much privacy . . . but God is present here and that makes this our heaven on earth.

The traditional dictum of Benedictine life, ora et labora, points to the essential unity between work and prayer. The Rule, then, orients work toward the end of the glory of God alone. This is a profoundly provocative witness, as Luigi Giussani continually emphasized, in a world whose only religion is work. Work is an essential aspect of a healthy human life.[13] But modernity has succumbed to the error of the tower of Babel; work has become a method of making a name for oneself, a path toward overcoming dependence and a way to grasp at power (Genesis 11:4). Paradoxically, in rejecting dependence and finitude of our lives, we have become enslaved. The Rule frees the monk from the slavery to autonomy, liberating him to enter into a harmonious relationship with creation and its Creator.

Ora et labora does not minimize the obligation of work. On the contrary, St. Benedict writes that “idleness is the enemy of the soul,” while work is an essential act of participation in the creative will of God. Properly understood, work is a response to the immense structural disproportion between the human person and her destiny; we are finite, but the Lord promises us the infinite, and we cannot help but respond to this gift with our whole selves. Thus, the horizon of human work is not its material output, but the infinite Lord. In the words of Psalm 127, “If the Lord does not build the house, in vain do its builders labor . . . In vain is your earlier rising, your later going to bed.” Under lockdown, then, work is not a burden but an essential path of recognition of the divine.

As the creative act of God culminated on the seventh day with rest, proper participation in his work requires obedience to the Sabbath structure of creation. Christ himself exhorted his apostles to “Come away by yourselves to a deserted place and rest a while” (Mark 6:31). Sleep comes naturally to the heart that depends on the Lord as a child does, for it knows itself to be held in the arms of its Father. As Charles Peguy tells us in The Portal of the Mystery of Hope:

He whose heart is pure, sleeps. And he who sleeps has a pure heart.

This is the great secret to being as indefatigable as a child.

To have that strength in your legs that a child has.

Those new legs, those new souls

And to start over every morning, always new,

Like the young, like the new

Hope

Rejection of this human limit leads to sleep deprivation, which is widespread in the modern era but wreaks devastating consequences on physical and psychological health. Those confined to their homes at this time would do well to attend to their need for rest, that their observance of the Sabbath may bring glory to God.

When governed by moderation, which St. Benedict considered the “mother of all virtues,” eating and drinking too can serve God. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the holiest room in a Benedictine monastery, after the chapel, is the refectory, for it is there that monks obey Christ’s command to serve one another (John 13:15). Through the breaking of bread together at table, those who are gathered in Christ’s name recognize the Risen Lord in their midst, a sacramental moment particularly essential for those who are unable to attend Mass.

In the disenchanted imagination of modernity, however, both food and the body that it nourishes are merely material and serve instrumental purposes. As a result, much of modern eating is disordered, for it is either an instrument for the unfettered satisfaction of physical desires or else a tool of manipulation in the pursuit of an idol of thinness. In the sacramental imagination of the Church, on the other hand, food is a gift ordered toward love, a means of unity and a symbol of the Eucharist. As food is one of few forms of leisure and celebration available under lockdown, this time is an opportunity to learn to relate to food and the body as a Christian does, with joy and gratitude, virtue, and charity.[14]

Thus, through obedience to a rule of life, each Christian can experience freedom within the monotony of repetitive days. Etymologically, the word “rule” denotes a signpost or a railing; the monastic rule is meant to guide and guard the monk or nun on the journey toward heaven. A daily rule, then, is neither a mechanical enumeration of requirements nor a moralistic standard of self-evaluation. Rather, it is a pattern through which the human person is educated to adhere to the initiative of Christ in her daily life. And so, obedience to a rule generates freedom, for as Paul Claudel writes in The Tidings Brought to Mary:

Is the object of life only to live? Will the feet of God’s children be fastened to this wretched earth? It is not to live, but to die, and not to hew the cross, but to mount upon it, and to give all that we have, laughing! There is joy, there is freedom, there is grace, there is eternal youth! . . . What is the worth of the world compared to life? And what is the worth of life if not to be given? And why torment ourselves when it is so simple to obey?

The authentically free person is the one who obeys the call of her destiny. No matter their state in life, and no matter the circumstances of their daily reality, all Christians are called to new life in Christ by virtue of their baptismal consecration. Even when Mystery is incomprehensible, even when the outcome is unknown, the person who adheres to Jesus is truly alive, for “no personality is more magnificently asserted than that of Christ.”[15] Now, more than ever, the path laid out by Saint Benedict can lead us to that ultimate destiny. Let us heed the call of reality.

[1] Robert Sarah, The Power of Silence (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2017), 83

[2] Kirste, Imke & Nicola, Zeina & Kronenberg, Golo & Walker, Tara & Liu, Robert & Kempermann, Gerd. (2013). Is silence golden? Effects of auditory stimuli and their absence on adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Brain structure & function. 10.1007/s00429-013-0679-3.

[3] Bernardi, L., Porta, C., & Sleight, P. (2006). Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory changes induced by different types of music in musicians and non-musicians: the importance of silence. Heart (British Cardiac Society), 92(4), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.064600

[4] Raymond L. Neubauer (2014). Prayer as an interpersonal relationship: A neuroimaging study, Religion, Brain & Behavior, 4:2, 92-103, DOI: 10.1080/2153599X.2013.768288

[5] Sophrony, His Life is Mine (Yonkers, NY: Saint Vladimir’s, 1997), 55

[6] Vail, K. E., Juhl, J., Arndt, J., Vess, M., Routledge, C., & Rutjens, B. T. (2012). When Death is Good for Life: Considering the Positive Trajectories of Terror Management. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(4), 303–329.

[7] Gerard Manley Hopkins, “God’s Grandeur”

[8] Fagard J, Esseily R, Jacquey L, O’Regan K and Somogyi E (2018) Fetal Origin of Sensorimotor Behavior. Front. Neurorobot. 12:23. doi: 10.3389/fnbot.2018.00023

[9] Feldman, R. (2017). The Neurobiology of Human Attachments. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 21, pp. 80–99.

[11] Kucinskas, Jaime & Wright, Bradley & Ray, D. & Ortberg, John. (2017). States of Spiritual Awareness by Time, Activity, and Social Interaction: STATES OF SPIRITUAL AWARENESS. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 56. 10.1111/jssr.12331.

[12] Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, Bloomsbury, 2013, 120

[13] McKee-Ryan, F., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and Physical Well-Being During Unemployment: A Meta-Analytic Study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53–76.

[14] For more, see Emily Stimpson Chapman’s The Catholic Table.

[15] Maritain, The Person and the Common Good, 32