Cormac McCarthy’s searing novels have as one of their main aims reminding us not simply that good people do bad things, but that in human beings evil goes all the way down to the roots of desire and the wellsprings of action. Monstrousness—that is, going beyond where we customarily draw the line regarding human evil—is an inherent capacity in human beings that makes human constructions of demons unnecessary, since, with regard to any evil that we might have conveniently attributed to these foreign entities throughout our fraught history human beings have successfully showed that they are capable of all that and more. The violence that seems to master us as a group is aboriginal and contagious; human rage comes from nowhere and inflicts harm on fragile bodies; malice appears to be omnipresent and is satisfied when other bodies have not only been hacked, but have been desecrated. Other bodies provide mere occasions for the exercise of our power and are effectively reducible to signs and tokens of our mastery over them: if the dead and mangled body is the ultimate sign, a body part, for example, the head or the scalp, serve as tokens of our everything and the victims nothing. Besides his constant (even obsessive) disclosing of the capacity in every human to live at the limits of transgression, McCarthy’s novels teem with monsters.

Blood Meridian provides an entire company of them in its depiction of a band of outlaws that create mayhem in the American Southwest in the middle of the 19th century. The cannibals in the post-apocalyptic The Road are hellhounds harvesting the bodies of the other survivors. As in Dante’s Inferno in a world of eternal winter cannibalism is the ultimate transgression because it is a sign of the absolute refusal to respond to or recognize another subjectivity. It would be easy to dismiss McCarthy’s darkness as an exaggeration meant to awaken us from our illusions of a world fundamentally secure from rage, malice, and violence. Of course, among other things McCarthy intends to shock and penetrate our defenses. But in another sense, McCarthy does not think that he is exaggerating at all, or, if he is, his hyperboles of evil match the hyperboles of human existence that go over any boundary that we set it.

One of the more interesting monsters in McCarthy’s novels is the nameless Indian hitman of No Country for Old Men, who though hired to kill someone for a fee, puts aside money in the interest of ensuring that deeds like stealing from a drug cartel and betrayal are punished with deadly violence. The Indian becomes monumental and precisely because he becomes the vigilante of another kind of justice, a justice that is more cosmic than ethical and legal. The selection of the perpetrator is intentional: while McCarthy pays attention throughout his work to the violence against Indians on the border lands, he wants to say that violence is aboriginal and thus the Indian is a primal who understands that violence has a logic, whether we call it fate or the logic of reprisal. This logic spares no one: it touches the innocent as well as the guilty. And it is not simply a matter of collateral damage: the girlfriend of the man who stole from the cartel is killed because the killing was part of the threat made to the robber who had to surrender his life as well as the money.

Looming above all monsters, even above the implacable Indian of No Country for Old Men, who is immune to pain and has chosen an air gun to inflict maximum damage on bodies and make them unrecognizable, is the Judge of Blood Meridian. The Judge is not local: he comes from “down under,” in this case Vandiemansland (Tasmania). We are expected, I presume, to free-associate him with the “Tasmanian devil.” The Judge is bloated, bald, and, in terms of physiognomy, wholly-other in that he remains ineluctably and inexplicably white and pink in the world of the Southwest that darkens everyone. Defined by his monstrous size and equally monstrous softness and shapelessness he fears no one and is feared by everyone, acutely so by Tobin the ex-priest who with the “kid” is the only one not mesmerized by the Judge’s awful glamor and thus able to see him as he really is.

Tobin is also the only character in the novel who has a language to name him. In his case this language is Christian language, and, more specifically, biblical and Calvinist language focused on the wrath of God. As Tobin uses this language, he cannot help but conform himself to Ahab in Moby Dick and suggest that the Judge is Meville’s “great white,” the principle of evil that roams the wastes of the world, in his case the wastes of sand and rock of the American Southwest, in Melville’s case the wastes of the ocean. Both wastes afflict the self and narrow the heart.

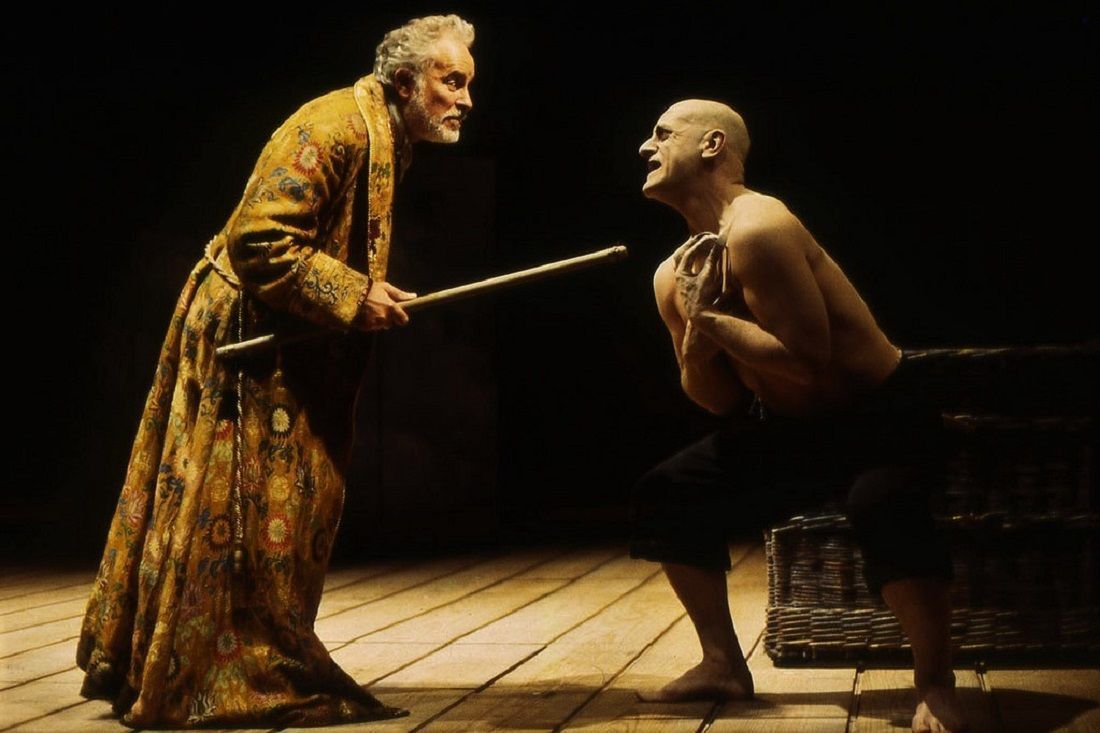

I will return to the figure of the Judge momentarily. First, however, a few remarks about the symbolic matrix of McCarthy’s masterpiece. Blood Meridian is about as polysemous a piece of American literature written in the past three decades as any, and the literary and cinematographic allusions are piled high. There are multiple allusions to Shakespearean figures either born as monsters or who in extremity have become monsters. The Judge, who in the second half of the novel is accompanied by an idiot in a cage, gives the kind of grandiloquent speeches about the accommodated nature of human existence in the wild landscape of the American Southwest that deliberately recall the great speech into the elements of the dethroned Lear who has moved beyond the pale of normal human experience, that is, into madness.

Not incidentally, Tobin and the “kid” speak of the madness of the Judge, although it is not clear whether madness is intended to suggest the privation of reason, or, as Foucault suggested, an economy that operates otherwise than the standard human logic that is a pottage of self-interest, self-assertion, need, and occasional flashes of human pity. The Judge also recalls the pure cynicism of Richard III but without the pathos of a twisted body or the excuse for malice. While McCarthy alludes in the novel to the Judge’s Falstaffian girth and garishness, in Blood Meridian this most human of all of Shakespeare’s characters, who loves the world and its pleasures, is transmuted into a colossus who hates and who wills to annihilate.

And finally, and tellingly, though any number of motifs in Blood Meridian recall The Tempest, for example, the constant reference to theatre, the stage, illusion, and fabula, in the case of the Judge we witness a blending of its two main characters, Prospero and Caliban, the latter pure urge, the former the controller and master of spectacle. Blood Meridian lays out uncompromisingly what we might suspect to be the ultimate truth of this most gorgeous of Shakespeare’s plays, that is, that Prospero and Caliban are simply two sides of the same phantasmagoric coin that should give us nightmares.

Two other allusions are worth mentioning. The first is an allusion to Heart of Darkness. McCarthy is a long-time admirer of Conrad, as he is of Faulkner, although in Blood Meridian he trades in one kind of Southern Gothic for his newly distilled one. The allusion to Conrad’s famous novella is, however, indirect rather than direct. McCarthy’s love for the cinema, arguably, provides a clue and in so doing demonstrates how symbolically layered McCarthy’s masterpiece is. The figure of the Judge seems to be threaded through its translation and retelling in Francis Ford Coppola’ Apocalypse Now (1979) and even more concretely by the figure of Marlon Brando as a bald and corpulent Colonel Kurtz.

There are biblical allusions also, even if they function more contrastively than not. “Evening redness,” which is featured in the subtitle to Blood Meridian, is a generic apocalyptic motif, as is judgment and its expression in writing in a book. “Evening redness” indicates a time of unveiling and the coming to knowledge, even as its connection with the main title suggests a horizon defined by the copious spilling of blood. While in Blood Meridian the figuration of judgment and the writing in a book recall the book of Revelation, they evince a reversal of sign. As in the book of Revelation, the judgment is rendered by the Judge on all of existence. Crucially, the Judge is not Christ, nor are the criteria of judgment governed by the witnessing to the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world. Rather the Judge is the Anti-Christ in that he has, like the Lamb, the aura of the terrible, but his wish is that all cease to believe in the personal God of the Bible, to renounce our allegiance to the one who preaches pity and exhibits solidarity with those who suffer and are broken, and to dispense with all morality—not only the hyperbolic morality demanded by Christ in the New Testament. There is but one world and it is an abomination and a world of sheer terror. This is also its terrible beauty.

At the same time both the presentation of the “book” and “writing” in Blood Meridian are deviant relative to their correlatives in the book of Revelation. In the case of the book of Revelation writing is the inscription of the would-be ephemeral persons of history into a book of life, which is a book of eternal validation of the innocent and the suffering and the guarantee of a compensatory joyous life in the presence of the Lamb who is the giver of meaning and the foundation of a loving community. In contrast, in the case of the Judge’s writing we are dealing not so much with a scroll which is itself a sacred object, but just a notebook to take what happenstance and hazard present to the eye and ear of a monster of bloodlust who is also the most pedantic of collectors.

Between the episodes of mayhem he participates in, and the mayhem he causes, the Judge depicts the flora and fauna of the American Southwest, records sundry facts of history and abstruse legal rulings, as well as his random philosophical musings. The notebook, however, is intended to be a book of the dead, not a book of the living. For the Judge once a phenomenon has been recorded law, it can cease to exist; more, it should cease to exist. All that is required is an image which is precisely a recognition of a something once having existed. Ideally, although more aim than realization, the goal is to inscribe everything in this book, the human and non-human, history itself. The book’s purpose is to enact a cosmic recall that is in effect a de-creation not a recreation and transformation into everlasting Life shared among a community of saints.

Nietzsche is to be accounted for throughout all of McCarthy’s novels from the 1980’s on. He is an intellectual and tonal presence in The Border Trilogy, No Country for Old Men, and The Road. Figurally, Nietzsche dominates Blood Meridian and ideologically saturates it. With respect to the Judge there are allusions to the figure of Zarathustra and a repetition of the grandiosity of the Nietzsche prophet preaching the “going under” and the “overcoming.” This is neither to speak to the Judge’s grandiloquent mode of speech, expressed equally in florid exposition and aphorism, which makes his discourse, just as much as Thus Spake Zarathustra, formally an example of the sublime. Nor is it to speak to the Judge’s Nietzschean-style haranguing about the new law and the new mode of legislation that precisely is not Christian, but, nonetheless, every bit as final.

Above all, however, we find in the Judge’s disquisitions on realty, which always take the form of absolute verdicts, Nietzschean set-pieces, which run very close to being parodies of the historical Nietzsche. One such set piece is a disquisition on sovereignty and its sublime irresponsibility. The Judge’s presentation (also recommendation) shows that he is aware of its roots in Machiavelli’s political philosophy, which cuts against the classical tradition by dismissing right for might, thereby dispensing with Plato and viewing as calumnies his figurations of Callicles and Trasymachus in the Gorgias and Republic respectively.

Sovereignty is a key term in the philosophical musings of Georges Bataille, whose Blue of Noon, arguably, serves as prompt at least for the title of McCarthy’s masterpiece, but probably no more given McCarthy’s commitment to the specifically American canon and pulp fiction. Although Sade is a literary and philosophical influence, broadly speaking Bataille inscribes himself in the Nietzschean tradition of critique and fundamental option for life that refuses to be suffocated by morality, whether conventional or religious.

As deployed within the Nietzschean horizon of Blood Meridian sovereignty is not inheritance, as it might be in Machiavelli. Rather it is a life defined by risk, ultimately the risk of life itself. Further, it supposes an absolute distinction between those born to rule and those born to be ruled. The guiding assumption is that the rules are the whim of the sovereign who has the life and death of those ruled in his hands. The Judge may or may not be mad. But if mad, then the reader must deal with the ambiguity of two options. The first option is to think of madness defined in a clinical and modern way as privative with regard to sanity, which is defined in large part by successful adaptation to reality. The second way is the way of Foucault in The Birth of the Clinic. Madness is not illogical; it is alternative form of logic that transgresses reason and has its own grammar and vocabulary.

Still, whichever form it is, the Judge is without a doubt a monumental narcissist. Anything he speaks to or recommends he already is. Thus, he is sovereign who rules over all without exception. It is this self-interpretation that makes it impossible for him to accept the defection of Tobin and the “kid” from his ghastly ranks. The Judge is made of far coarser stuff than either the historical Nietzsche or his mouthpiece Zarathustra. While speaking in a language of self-elevation gained through acceptance of the roil of what is, in Blood Meridian the Judge is considerably less squeamish than Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and more like one of the supermen of the future which strike even Nietzsche with a goodly amount of fear, not least of which is the difficulty of distinguishing between the superman and the underman who is a similitude of the superman, but ultimately a shapeless monstrosity and counterfeit. The Judge presents himself as a superman; Tobin and the “kid” discern in him an underman counterfeit.

The nihilism embraced by the Judge is as outsized as his body. Certainly, it goes beyond anything found in modern English literature, and, arguably, ideologically goes beyond anything asserted by Nietzsche. This is not to say, however, that McCarthy does not find prompts in Shakespeare and Melville, and encouragement in the novels of Golding. The words “nothing,” a “waste,” a “void” occur singly or in combination throughout Blood Meridian as the truth of things, their “bone” as it were. And the savage landscapes of desert and plateau are covered in bones, which at once recalls Ezekiel’s plain of bones and the paintings of Georgia O’Keefe. The instinct of the outlaws is to cover these landscapes with blood and add to the mountain of bone. This is the world of the Judge, the one world of Nietzsche, transient, painful, violent, and without rhyme or reason.

There is no beyond, just a “here,” which is the great dance of blood and death that includes all. Or, perhaps better, almost includes all. The Judge ambiguates as to whether it includes him, since his acceptance of the truth of the world, which is the truth of nothing and the sovereignty that is the only possible response, makes him the center of the world, not simply another item in the great dance of the world. At the very least the Judge claims that he is the master of the dance. This revelation is made by the Judge to the “kid” a decade after their murderous bloodletting and their attempts to kill each other after the kid’s and Tobin’s desertion.

To be master of the dance is to find its still center, which is possible only if there is punishment for desertion, which is as much in the mind as it is in fact, specifically for even having the mere stirrings (nothing more) of pangs of conscience. At their chance meeting, there is a chance dance, at which the Judge seems to preside, a chance need by the kid to go to the bathroom, a chance encounter in the outhouse, and a tearing apart of the kid which evokes horror in those that find the remains, the Judge having returned to the dance. In the end he who would resist is swallowed up by the narcissist for whom there is no other who cannot be reduced to himself. In this climactic moment exhibits the definition of the demonic and the monstrous as the destruction all that is other and the assimilation of everything to oneself.

McCarthy’s work is generally bleak, and no other book of his really rivals Blood Meridian in darkness and foreboding. It represents outright war against the American insistence on happiness and its penchant for forgetting its dark and bloody roots. This is not to say, however, however, that the monsters McCarthy visits on us come with his stamp of approval. He wants us to interpret them as coming from that dark regions of our history and psyche.

Still, here are witnesses of decency throughout McCarthy’s works, for example, the sheriff in No Country for Old Men, of course, the father and son in The Road, but also the father’s wife and son’s mother who despaired, as well as the family of three to whom the dying father hands off his son at the end of the post-apocalyptic novel. And, if only in pale form, Tobin and the “kid” have separated themselves enough to suggest the possibility of another world. Moreover, although evil is a capacity in all of us, McCarthy does not fail to render the innocent. Sticking only to Blood Meridian McCarthy does not fail to mention groups of Indians and Mexicans who are as peaceable as they are indigent and the true wretched of the earth.

The trouble is that innocence is powerless, and evil vicious. So it does not feel like a fair fight. Both innocent Indians and Mexicans are slaughtered by the motley band of demons led by the Judge in the seemingly endless crossing and re-crossing of the blighted landscapes of the American Southwest. Power and impotence constitute a binary, and there is no obvious way out. Perhaps there is hope against hope, but maybe not hope. If Christianity once provided a language of hope, that language appears to be used up. And so we are left in need for a language that we have not been granted, prostrate, resigned with our arms outstretched in what might be considered a plea.