There is no more pressing question for Christian intellectuals than this: What is the future of Christian thought in general and metaphysics in particular? Metaphysics has returned with vehemence and this is an observable fact. But I am no positivist and thus I hold that all facts require interpretation. Hence, as soon as we accept that metaphysics has returned one must immediately ask is this metaphysics qua metaphysics, or is it a specific style, form, and performance of metaphysics that has returned with vigor? Has one form or style risen particularly triumphant—like the phoenix—from the ashes of postmodern suspicion, a suspicion that has rightfully called into question the Titanism of philosophical modernity and our need to think finitude?

My answer is that—yes—in our current atmosphere of the metaphysical sea change that I am advocating for the analogia entis proves to be the most viable candidate. Not, however, because of its power, but because of its renunciation of power. Here with Paul power lies in its weakness, wealth in poverty, metaphysical gusto in mindful humility. Why? Because analogy’s metaphysical life has been saved in losing itself through embracing the foolishness of the Cross. Analogy’s wisdom lies in its metaphysical figure which is configured to Christ in an acceptance that fully embraces the positive “wound” (Chrétien) of our creaturehood lived out in radical openness before the mystery of the ever-greater Triune God of love. In a word, it is a metaphysics of the double gift of creation and recreation that breathes only in receiving and whose very life is a spiration of giving thanks.

By no means am I diminishing other possibilities or practices of metaphysics. This would be the folly of hubris which analogy renounces in order to live. Yet, I will show my cards upfront. I hold that the most urgent question for Christian intellectuals today is the question of how Christian metaphysical glory—which is always a reflected ray of Christ’s glory—is to return on this far side of history given the radical events of metaphysical closure that have taken place post-Hegel. To borrow from Desmond, I think that there is an “urgency and ultimacy” to thought and that any Christian metaphysics that cannot address the great metaphysical thought-events of our time as seen most powerfully in Hegel, Nietzsche, and Heidegger runs the risk of losing all vitality and visionary power.

Of course, there have always been and will always be different forms of Christian metaphysical glory. This is part and parcel of Christianity’s polyphonic glory. But these figures of glory were responses to Christ, and were responding to the “signs of the times.” What are the signs, and how do we discern the spirits with John, Paul, and Ignatius? I think we must take seriously the Balthasar of Theo-Drama and ask if the time of the “epic” (medieval summa) and “lyric” (spiritual treatises) have passed away.[1] Or, less strongly, if they have not passed away are they up to the task of meeting today’s radical challenges to Christian thought? Does the glory of Christian metaphysics now need to reflect something of an apocalyptic light? Does the sea change and the return of Christian metaphysics have enough left to offer one last metaphysical pièce de resistance?

My suggestion is that the metaphysical sea change that is underway in Christian philosophy and theology must fully assume an apocalyptic status. But here my intentions are much more modest and indeed propaedeutic in nature. I would like, all-too-briefly, to underscore and merely frame why an apocalyptic response is called for today, thereby negatively showing why an analogical metaphysics must glow within an apocalyptic light. If I was elaborating fully the positive meaning of apocalyptic, I would show how it resides not in an interpretation of Christianity as a religion of revelation. But rather in showing that the very mystery of Christianity is that it is revelation, it is the apocalypsis of Triune love opened through the Incarnation of the Word made flesh, made real in his death upon the Cross, and transfigured by his glorious Resurrection.[2]

Here I will only build to this understanding of Christianity as the apocalypsis of Triune love. In keeping with my propaedeutic approach my purpose is twofold: First, I limit myself to showing the minimum reading of the Christian tradition which is requisite for an analogical approach to Christian metaphysics, as this approach is necessarily deployed in apocalyptic unfurling of the Christian visionary tradition. Second, I will offer a bricolage of the kinds of challenges Christian metaphysics faces today, thus showing and framing, negatively, why an apocalyptic modality of analogical thinking is called for today and is, dare I say, our future.

A Capacious Reading of the Tradition and the Need of Metaphysics

An analogical metaphysical vision is possible only when it immerses itself within the capacious expanse of the Christian tradition. Indeed, one could argue that the large-scale denial of metaphysics is resultant upon our unwillingness or inability to creatively resource the great tradition of Christian thought. It cannot be an ahistorical approach to philosophy as seen in much of the analytic tradition which is, strictly speaking, not a tradition. Nor can it accept a full-blown postmodern reading of the tradition that sees the whole history of Christianity and the West as a tradition governed solely by violence and exclusion. Rather, it must reside in a hermeneutic of non-identical repetition which is a peaceful marshalling and orchestration of the visionary expanse of tradition.

This approach is encapsulated in two phrases from the Christian tradition. The first is in the spirit of Clement of Alexandria: vetus in novo patet, novum in vetere latet [roughly, the new was latent in the old]. This, of course, applies to the paradigmatic reading of the Christian tradition’s revealed history as exhibited in the relation between of the Old and New covenant. But this brilliant hermeneutic approach can be equally applied to a Christian metaphysical reading of the perennial and sapiential tradition of Western philosophy. Christian Wisdom is anticipated in pagan Wisdom which, in turn, requires a taking-up of this Wisdom in a baptism by Christian fire.

This is nothing new but is precisely done in the spirit of the Alexandrian spoils of the Egyptians. This spirit carries over to Augustine and the majority of Church fathers. And this same spirit is imbibed by Aquinas and Bonaventure, and the figures of the high Middle Ages. And it is repeated in the great twentieth-century ressourcement thinkers as well as in the various schools of creative twentieth-century Thomism be it “transcendental,” “existential,” or “speculative.”

This implies a second phrase from Augustine which sees that the Western sapiential tradition of philosophy is an una verissimae philosophiae disciplina [one true philosophical discipline].[3] But this one of philo(-Sophia) is no logocentric monolith, it is a tradition of traditions in a stream of memories centered in the mystery of the one and the many that lives from within the wellsprings of wondering astonishment before the question of the metaphysical mysteries of being and beings. It is a tradition expressive of an analogical unity-in-difference.

This tradition—to deploy a celebrated line from Augustine analogously—is ever-ancient and ever-new in which one enacts an ars memoria of the tradition which seeks to blend the voices of the past with modern and contemporary voices in a polyphonic addressing of the questions of our present exigencies—the “signs of the times”—from out of the past, in light of the future. This capacious approach then seeks to follow the lead of the magisterial lights of twentieth-century Catholic thought, by enacting the art of “transposition,” as Marechal would say.

The spirit of this reading of the tradition is one of a generous and dynamic orthodoxy rooted in the plurivocity of the Christian tradition which seeks to ask anew with the aid of the voices of the past: “what is Christian thought, what is its origin, its meaning, and its eschatological end?” This approach is centered in the ethos of the Catholic tradition, but its desire and broadness extend into a deep ecumenical exchange with the brothers and sisters within the various traditions of Christianity so as to seek to better understand—together—the love and truth of the Word made flesh, the one after whom Christians are named, re-named, made new.

What drives the reading of the tradition that I am presenting is its conviction that if the profound questions of the origin, meaning, and end of Christian thought are to be properly raised then the hard task of metaphysical speculation cannot be ignored and the plurivocity of the voices of the Christian tradition must be listened to. What is desired is a reigniting of full Christian Wisdom beyond the prosaic “immanent frame” (Charles Taylor) of our low breathless atmosphere in which we all attempt to breathe. But if this seemly absolute immanence (think: Deleuze and Agamben) is to be exploded then the transcendence and exteriority of the metaphysical is needed.

We all know that fire needs air, and I am suggesting that the air that we need most today is metaphysical analogical air—for did not the great Nietzsche also know the importance of the fresh enlivening air of the high icy peaks? Would this air reignite the fire of faith and does not “grace arrive along the path of being,” as Ferdinand Ulrich beautifully stated? I would hazard to say, yes, and that it was a disastrous and fateful error that ever thought that the metaphysical question of being could be separated from our humanity. This error is tragically and inanely accepted by not a few Christian intellectuals and is partly to blame for the great crisis of faith we are experiencing in the twenty-first century.

Anyone attentively observing the intellectual ethos and pathos of young and emerging Christian intellectuals sees that, like the deer that pants after water, many are now panting after the living waters of Christian metaphysical mindfulness. The sea change is well underway, but could one be so brass as to claim that this return of metaphysics is occurring within an apocalyptic space(s)? I see Zarathustra intently gazing at the sea and with his subtle nostrils smelling the coming of a higher history, while Christian thinkers sit contentedly alone in their studies or cells reading a commentary upon a commentary, impervious to the outside air.

An Apocalyptic Space(s) of False Doubles

Today’s thought-scape is like the tumultuous bustle of the agora—or better, the Areopagus, that hill of Ares—to which Paul brought the message of the unknown God, the incognito foolishness of the crucified and risen Word made flesh, who came to us hidden and will one day come to us again in glory. Paul’s situation, of course, is not unlike our own but it was also remarkably different. Both ages are reflective of a dizzying time of fracture and loss of foundations, a veritable marketplace of ideas. But the difference is that Paul was coming at the beginning of the announcement of the kerygma—whereas we do not know where we stand in this time that is “out of joint”—to borrow from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Heidegger is right that we are “latecomers”. And there is clearly truth that “the Owl of Minerva only takes flight at dusk,” but what truth and wisdom are gained and lost after the “end of history”? After the immanent attainment of the speculative visio beatifica?

Let me offer something of a bricolage. In the Hegelian progeny of the left-wing it is a mere radicalization of alienation. Clearly Absolute Spirit’s alienation from itself, must be pushed to Feuerbach’s alienation that returns the projection of humanity’s attributes into the divine sphere back into the man of flesh and blood—theology becomes anthropology—to Marx’s economic and material alienation of man from his own labor. There is a triad at work here: Hegel’s talk of Geist gives off too much the aura of the theological, whereas Feuerbach’s projection sounds too much like the aura of metaphysical transcendence, whereas Marx finally hits the nail on the head and banishes both auras in the wholly horizontal plane of material alienation, ending in the earthly coming of the kingdom.

This German triad of increasing radicalizations of forms of dialectical alienation sounds all too similar to the twenty-four-year-old French high priest of positivism (Comte) discovering his laws of the three states. For here too you have the analogous movement from the theological, to the metaphysical, to the final positive facts of the sociological. And, of course, Durkheim applauded this move because it shows that we are on the same footing as things. Is this not also why the late Comte would begin to fetishize the primitive fetishish religions and the affective and begin to see positivism as the fulfilment?[4] The of birth positivism and sociology is not only an anti-Christian and anti-metaphysical event, but it always harbored within it a dark tellurian underground, as its logical double. It is no accident that behind the founding of Georges Bataille’s College of Sociology—Durkheim being one it its idols—laid his real obsession, namely, the founding of a secret society which would refound the sacred through an actual human sacrifice.[5] There are never only facts but also always interpretations and metaphysical transcendence re-emerges even if it is inverted into dark Dionysian chthonic energies.

In speaking of the of the Dionysian underground I must not forget to mention the great Nietzsche. His tragic wisdom too sought transcendence even though he would deny its vertical reality. The youthful Nietzsche of Schopenhauer as Educator sought the great transcendence of the philosopher, artist, and the saint. And in the latter, he sought rightly the reconciliation of being and knowledge which, in a Christian view, is ever the end of the imitatio Christi. But how did this end? Nietzsche is no doubt a saint—and I mean this in all seriousness—because as Girard saw what is great in Nietzsche is not that he got anything right, but that he paid so dearly for being wrong.[6]

Like, his follower Bataille, he too wanted to reintroduce sacred violence, not through the sacrifice of another but through his own, perhaps, not unlike Kirilov of The Possessed. He sought a non-ritualized Dionysian transcendence. This is why the opposition—Dionysus vs. the Crucified—ended in his last letters in identifying with both Dionysus and the Crucified. Reconciliation of being and knowledge here ends in the tragic madness of nocturnal undifferentiation. But this collapse was rooted in an attempt to institute a higher sacred time and history where within the cycle of eternal recurrence the order of anti-Christ seeks to chase Christ away, as Deleuze both knew and applauded.[7]

After this bricolage, I ask again: where are we after the Hegelian end of history, after the owl has taken flight? We are in an apocalyptic space or spaces and we need an apocalyptic Christian wisdom![8] The aforesaid instances of post-Hegelian thought are what de Lubac rightly calls forms of “immanent mysticism” that seek to positively replace Christianity because, as Comte knew so well, something is not fully destroyed unless it is replaced.[9] To seek to refute these organic and constructive—yet mystical—forms of philosophy by mere logical rebuttal is folly. Rather, the full visionary, aesthetic, integrative, and dramatic expanse of the Christian mysterium must be unfurled, as alluded to above.

This unfurling is inseparable from a robust Christian philosophy of history that is metaphysically calibrated and reads philosophical modernity with Przywara, von Balthasar, and Ulrich as “pseudo-theology”. There has been the great reversal of the spoils of the Egyptians. The coffers of Christian mystery are blundered in a metaleptic re-writing of the Christian story, as Cyril O’Regan has masterfully shown. There is no pure philosophy in modernity. It takes a stance positively, negatively, and indifferently to Christ in the one trans-natural and concrete historical order that is situated in the theologoumenon of sin and redemption. Here, as Balthasar understood, nothing less than the pleroma of Christian wisdom will do, as we are not playing conceptual and univocal games.

We are dealing with doppelgängers, counterfeits, and counter-visions. I suggest some basic traits of philosophical modernity: with de Lubac that it must be seen as a denial of mystery, with Balthasar that it is the eclipse of Christian glory, and with Schmemann that it is a denial of authentic worship. This apocalyptic reading shares elective affinities with volumes IV and V of Balthasar’s Theo-Drama, aspects of Ulrich’s Homo Abyssus, Bulgakov’s reading of history in The Bride of the Lamb, Erik Peterson’s fabulous essay “Witness to the Truth,” and Girard’s reading of modernity as an apocalyptic time of prolonged stasis, to list some.[10] In a word, the spirit and vision of my proposal breathes from the spirit of Paul’s spirit but at the end of the day it is best described as Johannine: the spirit of Patmos.

Glimpsing the Future . . .

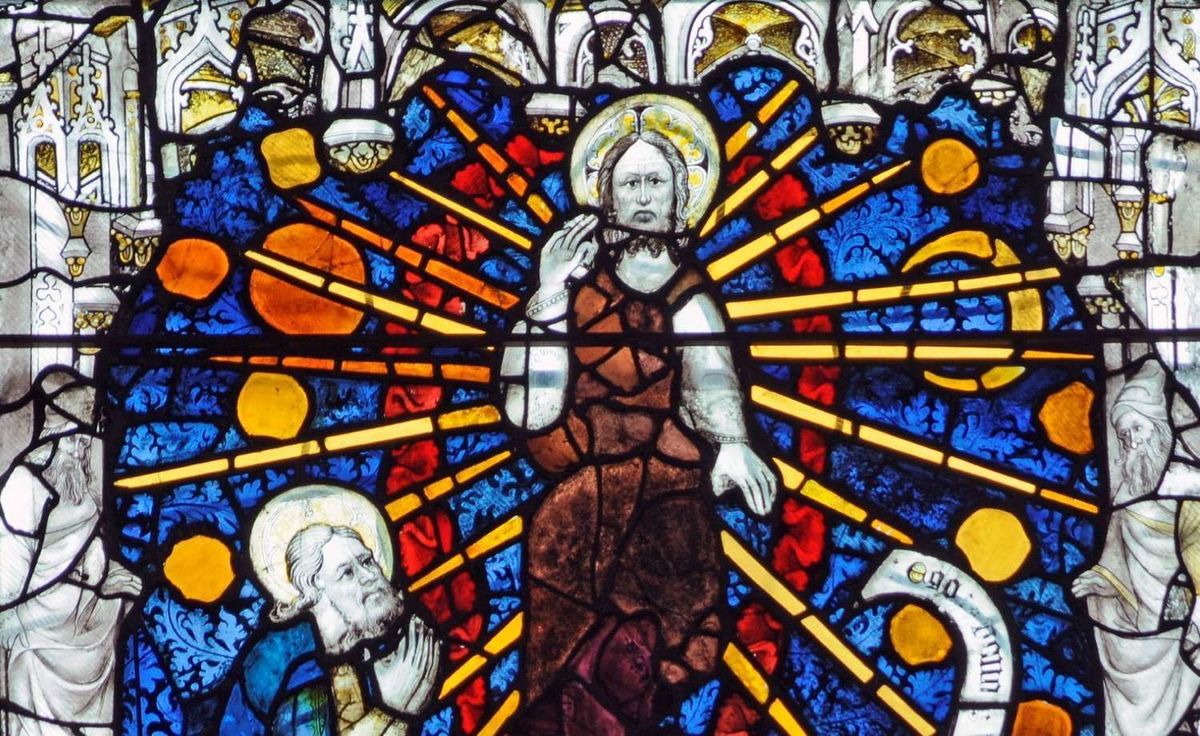

What is the answer, the future of Christian metaphysics amidst these apocalyptic spaces in this land of counterfeits? I hear the whispering of the insidious words of the Grand Inquisitor: 1500 years since Christ has come and not returned, and now—now—2000. But I also hear a counterword to the Grand Inquisitor’s: the ending of Solovyov’s Short Story of the Anti-Christ and I see the counterimage of Rouault’s depiction of Pascal’s Christ in agony until the end of the world. The answer—Christ—the one who was, who is and who is coming—the “only one,” as Hölderlin evocatively says.[11] We must, with Klaus Hemmerle, go in search of what is metaphysically distinct about Christianity, in this vesperal hour. This search will lead, as I have suggested, to the Christian mystery of the analogia entis.

This mystery, as Przywara and Ulrich intimated, deeply evokes Christ. These intimations are made fully explicit in Balthasar’s formulation of Christ as the concrete analogia entis or in the words of Rowan Williams, “Christ the heart of creation.”[12] All metaphysical desire is confronted by the mysterium Crucis. And one may only pass-over into this mystery of mysteries through the eventing-gift of metanoia through which is revealed the whole truth of the double gift of creation and recreation, being and grace, in light of the Trinitarian backdrop of all of being and history. History is the record, the arena, and the drama of created freedom’s response to the apocalypsis of uncreated Triune love revealed upon the Cross, wherein being is unveiled as commercium and kenosis, as the transubstantiated communion of agape.

If metaphysics is to fully return it must be analogical and if analogy is to answer the realm of false doubles, it must be recast apocalyptically. And this means that analogy must be Christocentric and Cruciform. And this implies that it exists only as a metaphysics which gauges created freedom and history as a response to the apocalypsis of Triune love opened in the event of Christ. Christ is the pivoting of history around which humanity’s apocalyptic desire turns and is turned. Here, thought is the site of conversion. And an apocalyptic recasting of analogy is simply the metaphysical story of the denial and acceptance of the Triune Being-of-Love.

Is this story now entering its denouement? No one can answer this question, but it does seem that we are at a point in history where—to echo Balthasar—only love is credible. Metaphysics today must “catch fire” and “draw flame” (Hopkins) by living within and from the apocalyptic glow of Christ’s love which shows us the Father’s love, bound in the unity of the burning love that is the Holy Spirit.[13]

EDITORIAL NOTE: This article is a revamped and expanded edition of the opening talk “Plurivocity and the Voicing of the Future of Christian Metaphysics,” given at the international Zoom conference, The Future of Christian Metaphysics, hosted by St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth, 29 April 2021.

[1] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Theo-Drama: Theological Dramatic Theory, vol. 1: Prolegomena (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), 42.

[2] This implies a reading, following Balthasar, of the tradition as being grounded in Triune “traditio”, that is, its origin resides in the very handing on of the Father in the eternal begetting of the Son, as is central to vol. 4 of Theo-Drama. This motif is deepened and expanded by O’Regan in The Anatomy of Misremembering.

[3] Augustine, Contra Acad. III, xix, 42.

[4] Here I am in agreement with de Lubac’s reading of Comte. See, The Drama of Atheist Humanism (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995), 131-167.

[5] See, generally, The Sacred Conspiracy: The Internal Papers of the Secret Society of Acéphale and the Lectures to the College of Sociology (London: Atlas Press, MMXVII).

[6] See Girard, “Strategies of Madness—Nietzsche, Wagner, and Dostoevsky,” in To Double business bound: Essays on Literature, Mimesis, and Anthropology (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1978), 76.

[7] See Deleuze, Logic of Sense, 340.

[8] See my, Reimagining the Analogia Entis: The Future of Erich Przywara’s Christian Vision (Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2019). Foreword by Cyril O’Regan, 321-354.

[9] See, Drama of Atheist Humanism, 11.

[10] Girard’s greatest apocalyptic statement and testament is, no doubt, Battling to the End. But for the motif of stasis I am thinking of an interview with Cynthia Haven.

[11] See Hölderlin’s later hymn “The Only One,” which along with “Patmos” shows the deeply Johannine element of some of his hymns. This shows how devious Heidegger’s reading of Hölderlin really is as he will not even touch this Johannine Hölderlin, but passes over it with a silence that is deafening.

[12] See Williams, Christ the Heart of Creation (London: Bloomsbury Continuum, 2018) esp., 219-254.

[13] I will develop my apocalyptic recasting of the analogia entis—centered in the Lamb slain—in my 2022 paper: “Analogical-Apocalypse: Metaphysics as Trinitarian Response,” at the conference The Future of Christian Thought, St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth, Ireland.