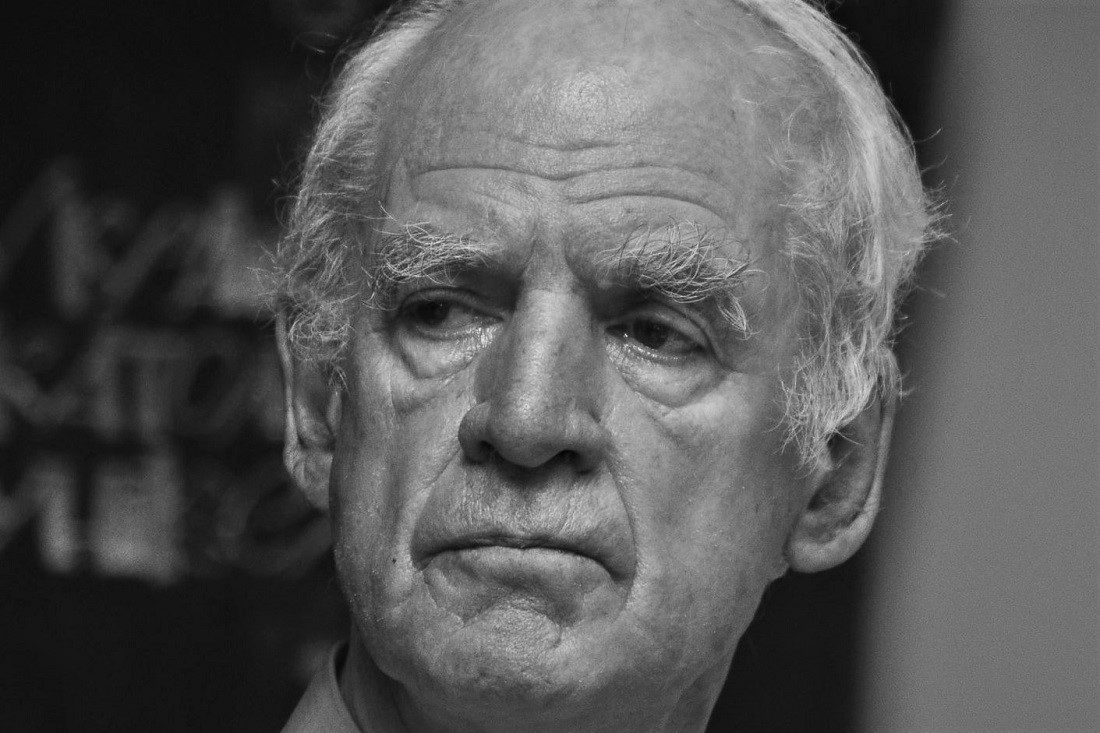

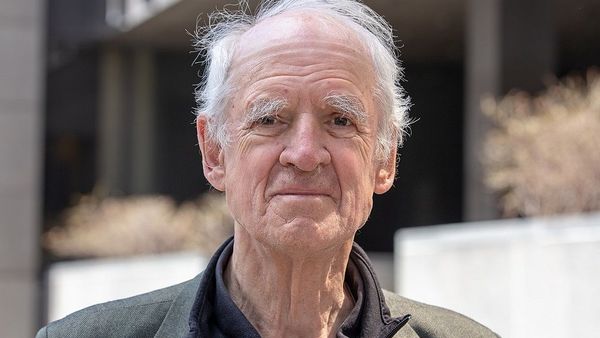

I wrote extensively elsewhere about possible substantive reasons why many Catholic intellectuals are attracted to Charles Taylor’s work. Among those reasons were his ability to reconcile the advent of modern culture with religion; moral realism with historical consciousness; sources of fullness with morality or ethics discourse. In addition, Taylor gives voice to many modern goods, but seeks to ground them more deeply in a moral realism of goods rather than in mere codes or rules. Such grounding then requires reevaluation of those goods themselves in relation to one another. Importantly, Taylor includes stories of conversion from figures such as Ivan Illich and Charles Peguy, whose experience breaks through a closed immanent frame to a source of fullness that contextualizes all other goods and supports communion. There is in this vision a deep and abiding Christian humanism. Finally, Taylor does not think that we can simply make the saints of the past an easily accessible Google map for the future; rather, each of us must either connect with those saints from whom this fullness radiates, or the source itself, or both, and find saints for our own time.

Now is the time to raise some questions or worries with respect to Taylor’s narrative and what it means for Catholics. In other words, we might wonder whether what Taylor offers is a particular version of Hegelianism and, if so, whether that Hegelianism can support a full-throated ecclesial commitment. On the one hand, it seems that Taylor's narration does have room for Catholic sensibility, and perhaps commitments, insofar as he wishes to ground a sense of goods and loves in a transcendent source of fullness that expresses itself in the world through sacrament and community. On the other hand, insofar as Taylor's method is thoroughly dialectical and immanent and suggests that history is somehow self-correcting, or to the extent to which the role of the Church and centrality of Christ remains unclear, it would seem that Taylor falls toward the Hegelian side of things. This “fall” will prove ecclesially challenging. The prima facie case for Hegel is strong: Taylor's massive tome on Hegel offers, in the main, positive assessments of the thinker, as do his crucial essays on Hegel as fundamentally important to practical reason and a discourse of freedom. This type of querying of Taylor, in the confines of a short essay, can only be a sort of probing and nothing like probative. Taylor’s work is too complex and nuanced for a simple verdict to be rendered here. Prior to approaching this question, however, we would need to address a fairly obvious and seemingly potent objection, namely that Taylor is not doing theology and so ecclesiology and/or Christology are clearly outside of his purview.

This objection is not nearly so persuasive as it first seems, for several reasons. First, precisely because he wishes to replace a moral discourse of rules/laws with one of Goods, Taylor includes modes of connection to sources of fullness within his overall schema. Taylor is fully aware of this. It follows, then, that Taylor’s method permits him to bring in views on the Church and its relation to contemporary political and social reality, which he in fact does in his work. Second, during the course of his historico-ethical discussions, Taylor includes elements of Christian belief that, for instance, someone like Kant will generally marginalize or massively re-interpret: grace, divine mystery, sacrament, sin, agape, eternity, sanctity, and so forth. Just as Taylor rejects the fact-value split or the imperialism of disengaged reason, so too he rejects the relegation of religious goods and terms of relation to the margins whether historically or systematically. Indeed, the former rejection allows for the latter inclusion. Thus, theologically-inflected terms and goods abound in Taylor’s discourse. The question, however, becomes what status do these goods have and how they may suffer significant change through their inclusion in his broad narration?

We will first discuss the role of narration as recovery of goods and argument in Taylor’s work, then address precisely how this narration relates to the Church in what Taylor calls a “post-Durkheimian age.” Here, questions arise with respect to the Church’s proper role vis-à-vis the contemporary political landscape. Next we will investigate whether Taylor’s form of narration allows for the finality of Christ’s person and where authority rests in his telling of the story of modernity. From this we will move to a consideration of what a saint might look like in the context of a post-Durkheimian world. Finally, we conclude with reflections on possible counter-indications in Taylor’s work.

Narrative as Recovery of Tradition

Taylor’s career evidences a long-term concern to push against an ethically debilitating determinism. His various incursions against determinism gain steam from a particular reading of Hegel’s philosophy of mind as a philosophy of action and from his own attempts to recover through narration moral goods forgotten by critics and supporters alike. So, for instance, while “instrumental reason” has many detractors for its tendency towards domination of nature, Taylor reminds us that its original impulse was to support human flourishing and reduce suffering, both of which it has accomplished to a significant degree. This original impetus, then, can become a kind of immanent criterion for judging proper and improper uses of technology. In other words, recovery of the intended goods helps gain ethical leverage on instrumental reason itself.

Likewise, “authenticity” has its promoters and detractors. Taylor recognizes the dangers of romantic authenticity, but also finds in it, when contemplated more deeply, certain ethical requirements that help get beyond modern atomism, i.e., the necessity for dialogue and openness to varied horizons of meaning in the search for self-definition. Where it lurches towards radical anthropocentrism or narcissism, it betrays its origins in an anthropology that valued tradition, community and the embodied nature of existence. It also yields to an atomism that is, for Taylor, philosophically inauthentic. No one defines themselves outside of multiple relations to others and to the larger culture of which they are a part.

The form of argument here is important. Taylor thinks that within the story of Western culture, we become aware of certain goods. At times, we enjoy or lament results without recalling the original rationale for the goods or even the goods themselves. Historical narration is crucial to recover these goods. Narration, then, is no mere story, but informs us of cultural goods, recovers their meaning both positive and negative in light of later developments, and thus contributes to self-understanding and identity. Narration is part and parcel of arguments in a historically conscious era.

Post-Durkheimian Normativity

In several places, Taylor narrates Christianity’s relation to secular society in terms of three Durkheimian phases: Durkheimian or paleo-Durkheimian, neo-Durkheimian, and post-Durkheimian. Durkheim, we recall, viewed religious language of the sacred and profane as referring not to divine objects, but to the larger society itself. Thus, in Taylor’s idiom, a Durkheimian relation exhibits minimal distance between Church and society. His example here would be Christendom. Neo-Durkheimianism is mostly a modern phenomenon where separation of Church and State occurs, but there lingers a kind of overarching civil religion with fundamental agreements on basic ethical issues. Here, the various religious bodies work to infuse culture, including political culture and law, with goods and values. Post-Durkheimianism, where Taylor places the contemporary state of things, suggests that the Church serves as just one center, among many others, for access to a source of fullness and a spirituality, but for many stands divorced from secular political culture.

Of course it may be the case that Taylor uses these terms in a purely descriptive sense: “this is the way things are currently but the way things are carries no ethical or normative weight.” I do not believe this to be the case for several reasons. Taylor is clear in A Catholic Modernity that for Christian goods to have become more universally available, the specific mode of Church-world relation known as Christendom (paleo-Durkheimian) had to whither away. So long as the division between “us” and “them” remained, the universalization of gospel values such as egalitarianism, human dignity, and compassion could not have occurred as they do once they are freed from ecclesial possession. The fall of Christendom is judged a good even if the good is not an absolute one.

We need to recall that Taylor’s telling of this long story is never just a story but is always intended as an ethical recovery. Different transitions in the story operate nearly in irrevocable mode. In narrating the Church-culture relation through Durkheim, then, it seems clear that his Durkheimian trajectory carries normative weight. He certainly thinks it a terrible mistake to long for a return of Christendom. If this reading is correct, then two related questions emerge:

- To what extent does Taylor think the work of the Church, understood as a witness to and sacrament of God’s self-revelation in Jesus Christ, is mostly already accomplished through the leakage of gospel goods into the broader culture in the wake of Christendom?

- A related question: to what extent does Taylor’s post-Durkheimian schema suggest that proclamation and mission ought to be either backgrounded or even extruded aspects of ecclesial purpose?

We might press these questions by way of the Second Vatican Council. In Taylor’s view, Catholicism is a desirable and perhaps authentic communal and sacramental approach to a transcendent source of fullness with a profound ethic of agapeic love. This rendition supports the Second Vatican Council’s call to universal holiness. Nevertheless, Lumen Gentium, to some extent, and much of Gaudium et Spes, would appear to fall squarely in the neo-Durkheimian dispensation.

The Council clearly accepts Church-state separation, but it also accepts mission and proclamation. Lumen Gentium views the Church as grounded in the Trinitarian missions and itself as on mission from this source. Gaudium et Spes envisions Christians working to leaven and transform the social, political, and economic landscape towards a vision of fulfilled humanity revealed and perfected in Christ. Methods and policies can and ought to be debated, but it is unclear whether either document would be consonant with Taylor’s post-Durkheimian recommendation save for prudential rather than systematic reasons.

The Finality of Christ

The primary context from which the Church draws its teaching on the finality or unsurpassibility of God’s self-revelation in Christ is that of Scripture. Scripture comes into form through the Israelites and their covenant with God on the one hand, and through the early Church and its experience of and testimony to the risen Christ on the other. God begins his dialogue with humanity from the very beginning, deepens that dialogue through Israel’s life, covenants (Law), prophecy, and national history, and gives his definitive Word in and through the life, teaching and passion of Jesus Christ. This word is definitive and unsurpassable because God’s ongoing dialogue or giving of his Word cannot “descend” any further than to have actually shared human history and nature. Two points seem important to emphasize here as they raise questions for Taylor and his narrative.

First, one must ask whether, for Taylor, Christ can have this kind of finality or whether, instead, Christ’s finality becomes not the ultimacy of his person, but of the agape, and related values, which he expresses. This question arises most clearly through Taylor’s discussion of the Reformation which, for him, brings to light the importance of the goods of ordinary life and gestures towards egalitarianism with the critique of two-tiered Christianity. While these goods are certainly in play for Luther, Taylor subtly interprets out of the story what appears to be central for Luther: fidelity to Christ himself or justification by faith alone. Put otherwise, it can look like Taylor’s historical interpretation of the goods that secular culture ultimately “receives” takes precedence over against the center of Reformation’s concern itself. Such an interpretation can then seem to weaken any prophetic voice the Church can have going forward as its goods get re-interpreted and transformed in light of an ongoing self-correcting narrative. Rather than God’s self-revelation as the primary interpreter of culture, as de Lubac would have it, Western history gains a certain hermeneutical authority perhaps over even biblical revelation.

Second, Taylor rightly abhors nomolatry, by which he indicates rules and codes for ethical behavior devoid of their rootedness in a deeper philosophical view of the person and arguments over the good. Taylor is not opposed to positive laws, of course, but does seem anxious—at times perhaps overly so—regarding ethical law. This may just be a corollary of his concern that modern ethical theory—and the Church insofar as it follows suit—reduces ethics to rules. Nevertheless, an important question does arise as to the significance of law to ethics and ethical discourse. Indeed, this issue relates directly to our first point with respect to the contest of authority: Scripture as interpreted through Church Tradition, albeit in all its complexity and historical pluriformity, or history as interpreted through a philosophico-ethical lens. The biblical form, to speak with von Balthasar here, includes not only expressions of agape, inclusion, equality, and dignity, but also law, justice, and judgment, and a transcendent God who is both uncanny and who elects and legislates.

The Saint?

One of the most interesting features of Taylor’s A Secular Age is the role saints play in his narrative. This is especially so in the chapter on exclusive humanism. There, saints interrupt Enlightenment assumptions regarding disengaged reason on the one hand, and the vitriolic figuring of “religious” people as fanatical, superstitious, and potentially violent on the other. Consideration of the saint, along with conversion stories, returns towards the end of the text as well. The Saint connects with sources of fullness that bring all other knowledge (i.e., psychoanalysis) into a broader framework and move toward communion. Taylor seems to have a special affinity for Francois de Sales and Salesian spirituality though this is far from exclusive. Who might be a central figure for our time is more difficult to discern and a number of figures at least recommend themselves: Ivan Illich and Charles Peguy each receive treatment under the ambit of “conversion” stories. But there is a more provocative possibility as well: the figure of William James.

Taylor is critical of James on grounds familiar to Catholics: James’s rendition of “religion” and “religious experience” focuses too much on individual and extraordinary experience and excludes communal, liturgical, and sacramental foci in part because his antipathy to Catholicism blinds him to larger patterns. If James gets religion wrong on some key points, he is on the side of the angels when he argues against William Clifford’s skepticism and for the intellectual responsibility of faith. Skepticism does not come, he thinks, from mere neutral reason, but comes from a fear of being duped. Thus, one decides against the possibility of attaining more truth in view of the overwhelming concern for not being a fool. In other words, neither a decision against nor for faith emerges from disengaged reason. And, for James and Taylor, it is the case in many areas of life that only a commitment allows fuller dimensions of truth to become apparent (i.e., friendship). Faith is this kind of commitment and thus calls for engaged rather than disengaged reason.

Taylor’s discussion of James is important for our discussion in another sense. If it is true that James covers over some key aspects of religion, it is nonetheless the case for Taylor that he provides a remarkable window on the post-Durkheimian sensibility. Indeed, it may be that James’s description of “religion” functions better as a foreshadowing of twenty-first century sensibility than as a “scientific” description of religious experience. Indeed, James is able to articulate the two great options—skepticism or religious belief—and thus “focus the debate”in a way few are capable of doing.[1] This is his power and importance. He is, in Taylor’s words, “our great philosopher of the cusp.”[2] Here, to make my point, I must quote Taylor at length for, in some ways, this passage describes Taylor every bit as much as James:

He [James] tells us more than anyone else about what it’s like to stand in that open space and feel the winds pulling you now here, now there. He describes a crucial site of modernity and articulates the decisive drama enacted there. It took very exceptional qualities to do this. Very likely it needed someone who had been through a searing experience of “morbidity” and had come out the other side. But it also needed someone of wide sympathy, and extraordinary powers of phenomenological description; further, it needed someone who could feel and articulate the continuing ambivalence in himself . . . it is because he stands so nakedly and so volubly in this exposed spot that his work has resonated for a hundred years, and will go on doing so for many years to come.[3]

This passage not only describes the feeling about Taylor one gets from reading A Secular Age, but also has a kind of hagiographical aesthetic to it. James seems to be figured as a kind of desert father for modernity: ascetic in his openness and refusal to decide; exposed to the ideological elements which, we know, can be every bit as harsh as the environmental ones; and through this vulnerability and sensibility, capable of searing insight. Jamesian “open space,” as Taylor refers to it in A Secular Age, is rarefied air. Although Taylor surmises that James was a man of faith, he never uses the word “saint” for James. Nevertheless, his description and aspiration gesture, at the very least, to the possibility that James is Taylor’s saint for our post-Durkheimian world.

Conclusion

I have assumed throughout this piece a Hegelian rendition of Taylor’s work. This is a kind of ethical Hegelianism that operates without closure and so is “soft” in Edmund Waldstein’s terms. Nevertheless, there is an immanent dialectical process of history that seems to self-correct over time, not without backsliding or retrograde survivals of course. Taylor’s narration of Western intellectual and cultural history provides much solace for Catholic thought. Nevertheless, it also raises important questions with respect to its implications for Catholic sensibilities and commitment. These questions emerge when we examine his way of telling the story of the Reformation and in his rendition of a post-Durkheimian age. In the end, we might put the questions in a pointed way. Are Taylor’s claims against atomism and for community, in the end, the same as Hegelian critiques of atomism and an option for a kind of romantic community ethos? Or, alternatively, are they claims for this ecclesial community and its mission; do his claims for agape ultimately mean something like a commitment to the One in whom such love becomes possible, or does agape becomes a generalizable good precisely due to the weakening of the Body of Christ as a social-political player. Does the term “saint” involve an ecclesial mission for the world, or more something like the figure of William James able to stand in the eye of the storm of modernity with equanimity? Like James, Taylor leaves us in the open; he clarifies the choices to be made, but restricts his own judgments lest temptation closes the space itself.

It seems clear that Taylor is not finished writing and it is entirely possible for him to answer the questions I have put to him. Taylor’s argument might develop a full articulation of goods such that he can say, at some point, that these goods find their deepest integration in Catholic teaching and forms of life: community and tradition in a Church that is the Communion of Saints; authenticity in a life lived agapeically; valuing the ordinary life, but also a vocation to celibacy with respect for renunciation of this life’s enjoyments on behalf of others. The issue of celibacy here is an interesting one: Hegel has no truck with it in his Phenomenology of Spirit. Indeed, he sees renunciation as emblematic of a God of the beyond and thus human alienation (B.IV.#225-230). This perhaps recessive reading of Taylor would suggest that Hegel’s method, while helpful, will ultimately find its resolution in Catholic tradition such that its content fills and bursts the bounds of dialectical method which must, in the end, be relegated to distant analogy. Of course, the Hegelian argument remains the prima facie stronger one. But were one to want to pursue an alternative reading, ammunition would not be lacking. Either way, one would have to choose.