Careful readers of Scripture committed to its truth as an article of faith often face challenges when its details stand in tension and even contradiction. Examples are easy to produce: Was the Passover celebrated on Thursday evening prior to our Lord’s crucifixion (as asserted by the Synoptic Gospels) or on Good Friday (as asserted in John; cf. John 18:28)? Were land animals and birds created prior to humans (Gen 1:20–27) or after (Gen 2:19)? Did Judas return the price of his betrayal (Matt 27:3–10), or did he use it to buy the field in which he died (Acts 1:18–19)?

For readers who understand Scripture to be without error (cf. Dei Verbum § 11), these kinds of questions produce anxiety and cry out for some kind of answer. Some scholars and apologists are eager to provide answers in the form of harmonizing readings that seek to eliminate or downplay the apparent contradictions. This instinct for harmonization generally arises from a pious and laudable commitment to the truth of Scripture. Nevertheless, as a general reading strategy, harmonization can result in seriously impoverished readings that fail to do justice to Scripture’s true richness.

Scripture vs. Reconstructions

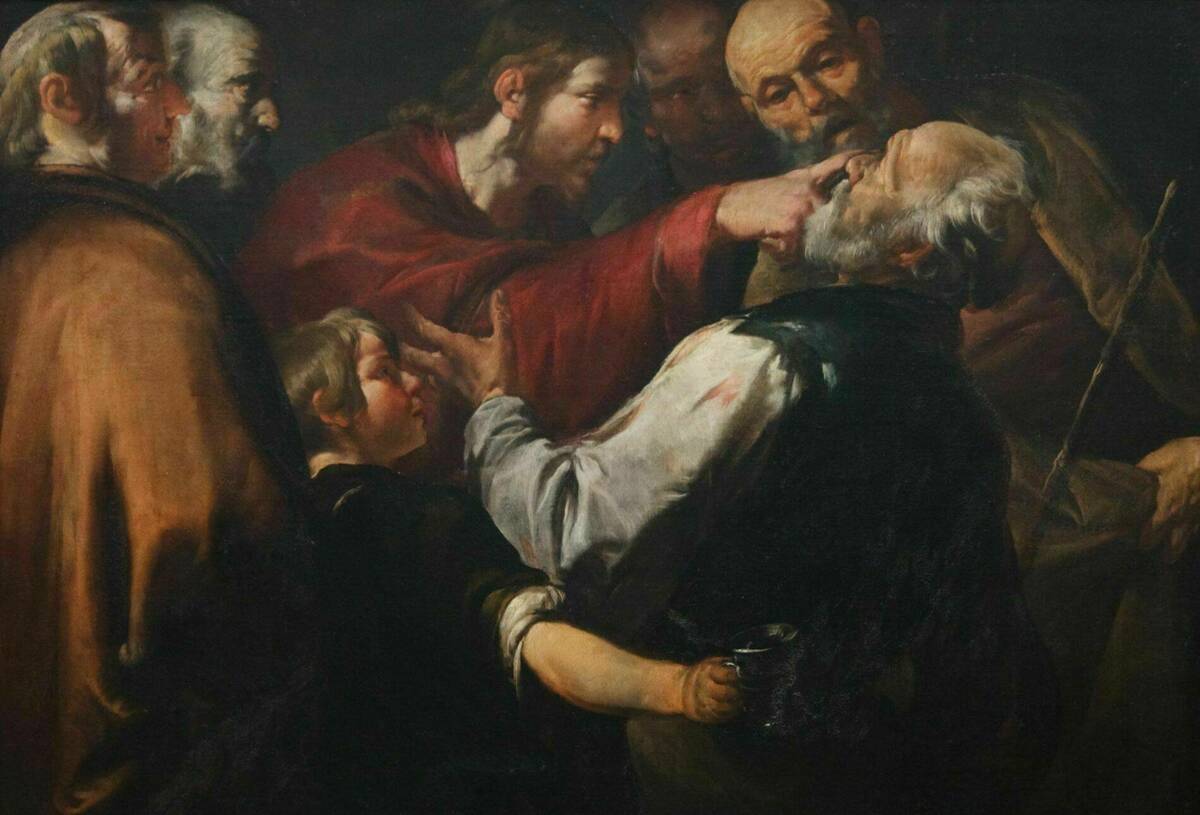

One problem is that harmonizations can end up substituting an extra-biblical reconstruction for the sacred text itself. Take, as an example, the healing of blind Bartimaeus. According to Mark 10:46–52, Bartimaeus was healed while Jesus was on his way out of Jericho (Mark 10:46–52; cf. also the two unnamed blind men in the parallel in Matt 20:29–34). Luke, clearly telling the same story, has him healed while Jesus was entering, not departing from, Jericho (Luke 18:35–43). The detail might seem inconsequential, but it presents an irritation for readers committed to the truth and inerrancy of Scripture. Consider the solution to this problem proposed by Karl Keating, founder of the apologetics website Catholic Answers:

Certainly all these passages refer to the same incident, so how can the two apparent inconsistencies (one man versus two, entering the city versus leaving it) be reconciled? Here is one way: Bartimaeus called out to Jesus as he and the crowd entered Jericho, but in the commotion Bartimaeus was not heard. By the time Jesus left the city, Bartimaeus had been joined by another blind man.... Bartimaeus calls out again and this time is heard because the crowd is now subdued. Jesus cures him and the other man.[1]

In order to make this harmonization work, Keating introduces the motif of Jesus’s failure to hear and respond to Bartimaeus’s first pleas for mercy. What is striking here is that the key to the harmonization contradicts a key point on which all three canonical accounts agree: Bartimaeus’s persistence in crying for help is met with Jesus’s immediate response. Insofar as these accounts describe one of Jesus’s many potent miracles, they also assure their first-century Christian readers (and us) that Christ hears us when we call out to him in prayer.

What Keating gains in his harmonization is the apparent removal of one more contradiction in Scripture. But this comes at too high a price: details of the canonical accounts that could be central to their theological interpretation (in this case, the assurance that Christ hears and responds to our prayers) have to be sidelined or minimized to make room for harmonization. We have three canonical accounts of this healing. Keating has proposed a fourth account—a reconstruction of his own devising—that diverges theologically from the canonical accounts.

Rather than a problem to be solved, these kinds of texts can and ought to be an opportunity to learn from Scripture itself about the nature of its truth and how to read it. Whether Jesus healed Bartimaeus on the way in or out of Jericho seems trivial, but it illustrates the literary license that the sacred authors are inspired to take in their narration of events and shows that Scripture’s truth is not the same thing as strict facticity. The sacred authors in their own ways present what Jesus said and did and adapt it for their own literary/theological purposes.

It is true that the result is that, on occasion, we cannot know the ipsissima verba, or decide with certainty what a video camera might have recorded had it been there. Phenomena like the contradictory accounts of Bartimaeus send us away from our reconstructions and back to the texts themselves, where we have something better than a video camera; we have sacred authors who, under the inspiration of Holy Spirit, have interpreted and adapted the sayings and deeds of Jesus “with that clearer understanding which they enjoyed after they had been instructed by the glorious events of Christ’s life and taught by the light of the Spirit of truth.”[2]

One Creation Account or Two?

The Pentateuch provides a particularly fruitful point of access to the question of how we might read inconsistencies in Scripture. As biblical scholars have long noticed, the Pentateuch teems with contradictions both in narratives and legal collections. What are we to do with a literature that is so beset with apparent problems? The well-known tensions between the creation accounts of Genesis 1:1–2:4a and Genesis 2:4b–25 provide an instructive example. There are several differences between these accounts, but perhaps the most striking is the sequence of the creation of birds, land animals, and humans. In Genesis 1, birds are created on Day 5 (Gen 1:20–23). On Day 6, God first creates land animals and then humans (Gen 1:24–27). By contrast, in Genesis 2 the human man is created first (Gen 2:7). Subsequently, after noting that it is not good for man to be alone, God creates all the animals and birds (Gen 2:19), and finally the human woman (Gen 2:22).

In their A Catholic Introduction to the Bible: The Old Testament, John Bergsma and Brant Pitre point out this discrepancy and ask “How is this to be understood?” Their answer is a harmonization of the two accounts in which Genesis 1 referrs to creation in general and Genesis 2 refers to the creation of agricultural creatures. They also point out that, alternatively, the contradiction could be removed by translating Genesis 2:19 as “God had formed every beast,” which would allow understanding it as describing the creation of animals in Genesis 1.

Neither proposed harmonization works, and it will be necessary to venture into the weeds of Hebrew lexical semantics and syntax to show why. It is worth noticing right away, however, that the fact that they provide two unrelated explanations provides important insight into their reading strategy. This is a methodology that begins not with the details of the text but with the conclusion that Genesis 1 and 2 must be harmonized in one way or another. Their first suggestion distinguishes the general creation account of Genesis 1 from the creation of domesticated animals in Genesis 2:

Genesis 2 is concerned with domestic plants and animals, not all living things per se. Genesis 2:15 notes the absence of cultivated plants, not all vegetation. Likewise, the animals created and brought to Adam (2:18–20) appear to be domestic animals, because their purpose is to be a “help” to him. Dogs and horses are potential “helpers”; sharks and vultures are not.[3]

This explanation allows them to validate their suggestion that the movement from the first creation account to the second could be understood as simply “a shift in perspective by the sacred author” rather than as two inconsistent sources.[4] But does the language of the text permit this interpretation? The text in question, translated fairly literally, reads as follows:

And the LORD God formed out of the ground every beast of the field and every bird of the heavens, and he brought them to the man to see what he would call them, and whatever the man called it, that is, every living creature, that was its name. And so the man gave names to all the livestock, and to every bird of the heavens, and to every beast of the fields, but a helper fit for Adam was not found. (Gen 2:19–20)

Bergsma and Pitre claim that “every beast of the field” and “every bird of the heavens” could refer exclusively to domestic animals. Besides the problem of how “every bird of the heavens” could refer only to the subset of domesticated birds, the phrase “beast of the field” is a common expression that means “wild animals” often with explicit reference to the danger they posed to both humans and domesticated animals (see Exod 23:29; Deut 7:22; Isa 43:20; Ezek 34:5; Hos 2:12 and many other examples). Leviticus 26:22 provides a good sense of the meaning: “I will send against you the beast of the field that it might bereave you of children and destroy your livestock.” Even worse, the immediate literary context describes the serpent as belonging to the category of “beast of the field” (Gen 3:1).

It is intriguing that after describing the creation of “every beast of the field and every bird of the heavens” Genesis 2:20 introduces a third category, livestock (behēmāh), which appears only in the context of the man’s naming of the animals. This term does refer to domestic animals but does not encompass all that was created in v. 19. Is it possible that the introduction of this third category of domestic animals reflects an understanding about the function of human language in the ordering of Adam’s world? Could the author be suggesting that it is precisely in assigning names to animals that Adam determines their relationship to himself and that, though no suitable helper is found, Adam does succeed in creating through language the category of domestic animals? Regardless of how we understand the relationship of v. 20 to v. 19, the language the text uses here simply does not permit understanding v. 19 to refer only to domestic animals.

Here we can note once again that the harmonistic approach comes at a price. If Bergsma and Pitre are right that only domestic animals are created and brought to Adam in Genesis 2:18–20, it would entail that Adam’s role in naming the animals would be restricted to naming the relatively few domestic animals. But the text tends in the opposite direction. It is not just domestic animals that are created and named but “every living creature” (Gen 2:19). The categories in v. 20 are intended to be inclusive: “all livestock,” “every bird,” “every wild animal.”

The theological implications of this are vast: God draws the man here into the act of creation, and he exercises for the first time a kind of royal prerogative that extends to the entirety of the animal world. As Claus Westermann puts it, “By naming the animals the man opens up, determines and orders his world and incorporates them into his life. The world becomes human only through language.”[5] Bergsma and Pitre, by contrast, restrict the man’s naming to domestic animals and so significantly narrow the theological scope of the narrative.

Perhaps recognizing the fragility of their domestic animal proposal, Bergsma and Pitre offer an alternative way of reconciling Genesis 1 and Genesis 2: Genesis 2:19 could be read as expressing a past perfect: “So out of the ground the Lord God had formed every beast.” This proposal also cannot be sustained. Classical Hebrew does have a syntactic construction that is regularly used to express anterior time (waw + nonverb + verb), but that construction is not used here. Instead, the verbal form selected by the author (waw consecutive imperfect) almost always expresses past action that follows in temporal succession with the action of the previous verb.[6] It would be in keeping with the regular usage of these verbal forms to translate Gen 2:18–19 as “Then the LORD God said, ‘it is not good for the man to be alone. I will make a helper fit for him.’ And then the LORD God formed from the ground every beast of the field and every bird of the heavens.” Strictly speaking, it is possible in rare and highly marked exceptional cases for this verbal form to express anterior rather than consecutive action.

Nevertheless, regular usage entails that, all things being equal, the verb that begins Genesis 2:19 would be understood as indicating that the action narrated there followed v. 18 temporally. But all things are not equal and more can be said in support of the verb expressing temporal consecution. In v. 18, God expresses an intention to make a helper fit for the man. He will, in the future, make such a helper. And then, following logically and temporally from that intention, God forms the animals. And then he brings them to the man and the man names them. And then, when no fit helper is found, the woman is made. Each action follows logically and temporally from the last. Both literary context and grammatical rule agree: Genesis 2:19 describes an action that occurred after Genesis 2:18.

To achieve their harmonized reading of Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, Bergsma and Pitre have to obscure the meaning of words and grammatical forms and opt for contextually unsupported readings. Once again, we can ask whether the harmonization is worth the high price paid for it.

Benedict XVI’s Steady Hand upon the Tiller

I have dealt with the problems with Bergsma and Pitre’s harmonization at some length because it is important to recognize the extent to which harmonization can require stretching the meaning of the words of Scripture. Compare, by contrast, Benedict XVI’s treatment of the divergence between the two creation accounts in a short collection of homilies titled “In the Beginning . . .” A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall.[7] Benedict does not here get into the nitty gritty details but accepts as well established that these two creation accounts are written at different times by different authors. In thinking through the difficulties raised by these texts, he stakes the claim that the unity of Scripture ought to be the starting point for a Christian reading of it.[8] Here, Benedict XVI echoes the instructions of Dei Verbum §12, which urges serious attention to the “unity of the whole of Scripture.” Keating, Bergsma, and Pitre would all no doubt enthusiastically agree with this principle. In fact, they might well claim that it is precisely this unity that requires a harmonizing reading strategy. But Benedict XVI takes this principle of unity in the opposite direction. For Benedict XVI, the principle of Scripture’s unity leads him instead to notice and emphasize the differences in the variety of creation accounts.

Benedict XVI points out that the Bible is neither a textbook nor a novel, but rather “arose out of the struggles and vagaries” of the history of God’s interactions with his people.[9] He explains that “The theme of creation is not set down once for all in one place; rather, it accompanies Israel throughout its history, and, indeed, the whole Old Testament is a journeying with the Word of God.”[10] For Benedict, the principle of Scripture’s unity does not lead to a downplaying of the vagaries and diverse positions in this history, but rather it leads him to see the whole history of revelation as both divine condescension and pedagogy.

The unity is found not by interpreting away the different perspectives on creation (or any other theme) but by looking to the end: “Thus every individual part derives its meaning from the whole, and the whole derives its meaning from its end—from Christ.”[11] With this end in view, Benedict XVI returns to Genesis 1 to appreciate its historical particularity, how it differs from other creation accounts in Scripture, and how it points forward to this telos. Benedict XVI reads Genesis 1 in light of the Babylonian exile, which he takes to be its time of composition, and reflects on the particular message it had for Israel during that crucial and vulnerable moment.[12] He goes decisively further:

Immediately after it [the creation account of Gen 1] there follows another one, composed earlier and containing other imagery. In the Psalms there are still others . . . In its confrontation with Hellenistic civilization, Wisdom literature reworks the theme without sticking to the old images such as the seven days. Thus we can see how the Bible itself constantly re-adapts its images to a continually developing way of thinking, how it changes time and again in order to bear witness, time and again, to the one thing that has come to it, in truth, from God’s Word, which is the message of his creating act.[13]

In the end, Benedict XVI does achieve a kind of harmony in Scripture, but it is not a harmony achieved by grinding away the rough edges that frequently appear in the course of this splendid and messy history. To the contrary, Benedict refuses to eliminate the differences in the creation accounts for the precise reason that the differences that are there bring us deeper into the mystery of revelation, the mystery of God who enters into history in order to speak a word to his people. The various steps along the way and the manner in which one differs from the next are not embarrassing facts to be explained away; they are a key part of the story of the God who condescends to speak to us. To harmonize is to remove the “struggles and vagaries” of the history of revelation and thus to misconstrue its nature.

We can notice here the contrast between how Benedict XVI and the others view the task of the biblical exegete. For the harmonizer, the inconsistencies require reconciling the two (or three) accounts into one and even to be willing to read against the grain of the text’s plain meaning to achieve harmonization. Benedict XVI, by contrast, is not willing to pay this high price of harmonization, and takes the contradiction instead as an opportunity to learn something important about the historical character of divine revelation. Recognizing the contradiction provides not only a crucial key to reading Genesis 1–2 in the contemporary world, but also to apprehending the truth of revelation as divine condescension. Little is gained in harmonization and much is lost.

It is important to point out that Benedict XVI’s aversion to harmonization as a reading strategy is not unique to his treatment of the creation accounts. It pervades his exegetical work. He refuses, for instance, to reconcile the contradictory dates of the Passover in relation to Christ’s death,[14] or the resurrection appearances (which he bluntly describes as “rather awkward” “from an apologetic standpoint”),[15] or the infancy narratives and genealogies of Jesus.[16] In each case, he resists the harmonizing impulse and sees the contradictions instead as opportunities to enter deeper into the text and to apprehend the living word that meets us there.

Finally, let me hasten to add that I do think sometimes harmonization could be the right approach to a text. If so, it must be a conclusion that follows careful exegesis rather than its predetermined goal. Careful readers should consider all possibilities. But as we have seen, the impulse to harmonize, though understandable and pious, is not one that tends to produce good readings of Scripture. In most cases of apparent contradictions, the best approach is the one modeled by Benedict XVI: simply read both contrary accounts as equally true and as a window into the greatness of the God who condescends to speak to humans in human words in and through the struggles and vagaries of history.

[1] Karl Keating, What Catholics Really Believe: Answers to Common Misconceptions About the Faith (Ignatius Press: 1995), 35.

[2] Dei Verbum § 19.

[3] John Bergsma and Brant Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible: Volume I: The Old Testament (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2018), 102.

[4] Bergsma and Pitre, The Old Testament, 100.

[5] Claus Westermann, Genesis 1–11: A Commentary (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984), 228–29.

[6] See, for example, Christo H. J. van der Merwe, Jackie A. Naudé and Jan H. Kroeze, A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar (Sheffield Academic Press, 1999), 165–68; Bruce K. Waltke and M. O’Connor, An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1990), 547–53.

[7] Pope Benedict XVI, ‘In the Beginning …’ A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995).

[8] Benedict XVI, In the Beginning, 8.

[9] Benedict XVI, In the Beginning, 9.

[10] Benedict XVI, In the Beginning, 9.

[11] Benedict XVI, In the Beginning, 9.

[12] Benedict XVI, In the Beginning, 10–14.

[13] Benedict XVI, In the Beginning, 14–15.

[14] Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth: Part Two: Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2011), 103–15.

[15] Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth: Part Two, 265–67.

[16] Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2012), 8–9.