Nearly everyone has heard of Francis of Assisi, and it is certain that, after the Blessed Virgin Mary, he is the most popular of Catholic saints. His statue decorates many gardens and lawns, even those of non-Christians, and the Dalai Lama has offered him as a model for Buddhist monks. There is no question that Francis is an icon. The first non-European pope chosen in over 1200 years, a Jesuit at that, broke an almost equally ancient tradition when he chose a name that was not that of any previous pope. What did he choose to be called? Pope Francis.

Francis is a saint whose story has been told repeatedly. Yet, I, a member of the Dominican Order, never had much interest in, much less devotion to, the “Little Poor Man” of Assisi. That I would write his biography seemed, at least to me, highly improbable.

The universal online library catalog (OCLC), lists no fewer than 238 biographies of Francis published or republished in the last ten years alone, nearly twenty-five titles a year. Can anything new really be said about a man so well known, the subject of so many biographies? And how on Earth did I end up writing one? Before I found myself doing research on Francis's life, I did not think much remained to be said about St. Francis. By the time I finished that research, I had met a man that no one seemed to know, and I had been changed.

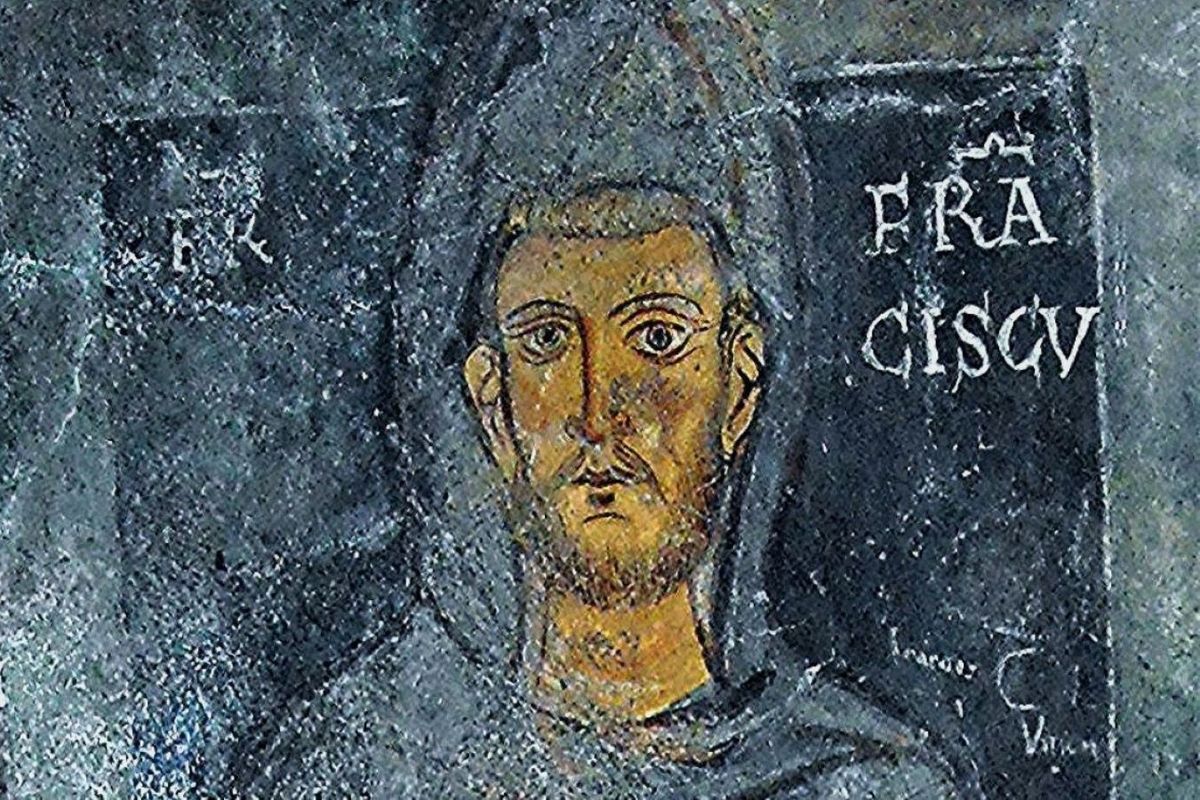

The Francis I encountered was quite different from those of the earlier biographies I had read. Even now, after writing a, by academic standards, best-selling biography, Francis of Assisi: The Life, I believe that much more remains to be discovered about this remarkable man and that, when found, it will both delight and challenge us today. In my portrait of Francis, which first came out in 2012, I sought to uncover the historical man hidden behind centuries of legends and appropriations. I found that I had to chart a way through the mass of stories, anecdotes, reports, writings, and interpretations that, from his own time to our century, confused and distorted our vision of the saint.

While writing my biography, I was forced to ask a series of questions about our early evidence for Francis. First, who wrote the text? Was it Francis, someone who knew him, or someone who just heard about him? Oddly, many modern popular biographies, I found, favor hearsay stories over Francis's own writings. Next, when was the document written? Within a few decades of his death in September of 1226, reports and stories about the saint underwent transformations that adapted them to new and developing concerns of the authors and audiences. Much elaboration and rewriting went on, and some stories about Francis were simply invented out of whole cloth.

Often these inventions involved miracle stories. These reports had to be evaluated with special care, not because I do not think miracles happen, but because Francis was a canonized saint, and for medieval people, adding more miracles to his “biography” was not fraud, but an act of homage and piety. The famous Wolf of Gubbio failed that test. It is impossible to prove that that peacemaking incident, in which Francis tamed a wolf who was terrorizing a small town, never happened; perhaps it did.

But as we have it, the tale was only written down a hundred years after his death, too late to accept without additional confirmation, which does not exist. To find the man behind the legends, I had to set aside such late reports, charming as they may be. On the other hand, I could not recount Francis's life without acknowledging the perception of miraculous power that surrounded his person after he became a “living saint” in his later years, and my biography included plenty of those reports. I also became more and more skeptical of any story in which the man Francis was made the mouthpiece, decades after his death, for a party involved in some debate within his own Franciscan Order, especially those about the practice of poverty, something that we now know was not a topic of great debate until at least thirty years after the saint's death.

My reading of the sources for Francis forced me to diverge from the usual story. The Francis I came to know proved a more complex and personally conflicted man than the saint of the legends. Nevertheless, this Francis became for me an amazing and holy man. I found a man who could not be assimilated to some preconceived idea of “holiness,” especially if it suggested that a “saint” never has crises of faith, is never angry or depressed, never passes judgments, and never becomes frustrated with himself or others. My Francis's very humanity made him—for me and for many readers of my biography—more impressive and challenging than the saint who embodied that (impossible) kind of holiness.

But I would also emphasize that my “historical Francis” is no more the “real Francis” than the Francis of the legends and popular biographies. He is “historical” insofar as the picture I paint is the result of historical method, not theological reflection or pious edification. That said, I do think that the Francis I discovered is closer to the man known by his thirteenth-century contemporaries than the figure we find in the modern biographies. And I do hope that my portrait reveals a Francis that will provide stimulus for new theological reflection and richer Christian piety.

As an academic, I came to Francis as an outsider. As a historian, I was new to the contentious and often bitter world of scholarly controversy over the historical Francis. Especially for his modern followers, the Franciscan friars, nuns, sisters, and lay tertiaries, how one imagines Francis and his concerns has powerful, sometimes highly divisive, implications for living one's life today. I have no personal stake in those internal Franciscan debates. As we Americans colloquially say, I don't have a dog in that fight.

But my encounter did challenge me religiously. Although I wrote principally as a historian, I am also a Catholic Christian, a priest, and a member of the Order of Preachers, the Dominicans, who are often considered the twin of Francis's own Friars Minor. As I hinted above, I never had much devotion to Saint Francis, and I always found it mildly amusing that we Dominicans refer to him as “Our Holy Father Francis,” using a title, “Father,” which he went out of his way to avoid. As I worked on my biography, my respect for Francis and for his vision increased, and he captured my affection and admiration. I hope my book will speak to modern people, believers and unbelievers alike, and that the Francis I have come to know will have something to say to them today.

My biography is intended for all readers who are interested in the saint. Some might even be scholars, who have spent years studying the Middle Ages, the Order of Friars Minor, or its founder. If they want to, they can hear about the debates, the medieval sources, and how I decided to interpret them. They will be especially interested in the second half of the book, in which I explain the scholarly controversies and the complexity of the sources.

Most readers who pick up my biography will, I suspect, simply want to hear something about the “Little Poor Man” himself. If the readers are in their sixties, as I am, they may have been introduced to Francis by Franco Zefferelli's film, Brother Sun, Sister Moon, the last and perhaps greatest monument in a line of romantic reinterpretations going back over a hundred years. In this tradition, Francis was a free spirit, a wild religious genius, a kind of medieval hippie, misunderstood and then exploited by the “Medieval Church.” Or perhaps they came to know him as the man who spoke to animals, a nature mystic, an ecologist, a pacifist, a feminist, a “voice for our time.” Some will come wondering just who is this eight-hundred-year-old saint that our pope chose for his patron. In fact, for some, he might be no more than the little plaster man on the birdbath, that most charming and non-threatening of holy men.

Like Jesus, Francis belongs to everyone, so everyone, or almost everyone, has his or her own Francis. And this is probably the way it has to be. In years of university teaching, I have often been astounded at how unhappy students can be when they encounter a Francis different from the one they expected. Oddly enough, the most painful moment usually comes when they discover that Francis did not write the “Peace Prayer of St. Francis”—a popular hymn best known by its opening words “Make me a channel of your peace,” and sung to a tune by Sebastian Temple. Many are quite shocked to find that this song is not identical to Francis's “Canticle of Brother Sun,” from which Zefferelli took the name of his movie. The “Peace Prayer” is modern and anonymous, originally written in French, and dates to about 1912, when it was published in a minor French spiritual magazine. Noble as its sentiments are, Francis could not have written such a piece, focused as it is on the self, with its constant repetition of the pronouns “I” and “me,” the words “God” and “Jesus” never appearing once. We all have our own “Francis.”

As a historian, I usually avoid suggesting what the past might mean for modern readers. But since the intensity of my encounter with him forces me to say something about what I have learned from Francis and how he challenged me, I will list a few things he has taught me as a Catholic Christian. I am sure he will teach others something different, so these reflections are purely my own.

First, he taught me that the love of God remakes the soul. Doing good to others does follow from this, but Francis’s message is not primarily about doing good to others. Francis was more about being than doing. And the “others” whom the Christian serves are to be loved for themselves, no matter how unlovable, not because we can fix them by our good works.

Secondly, rather than a call to accomplish any mission, program, or vision, to live the Christian life as Francis did demands a change in one’s perception of God and creation. Above all, it has nothing to do with success, personal or corporate, which always eluded Francis.

Thirdly, true freedom of spirit, indeed true Christian freedom, comes from obedience, not personal autonomy. And, as Francis showed many times in his actions, that obedience cannot be an abstraction, but must involve concrete submission to another.

Freedom means becoming a “slave of all.” Finally—and I hope this subverts everything I have just written—Francis taught me that are no ready and clear roads to true Christian holiness.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay comes from the “Introduction” (with slight revisions) of Francis of Assisi: The Life (now available as an audiobook wherever you get your audio products), by Augustine Thompson, O.P. Copyright (c) 2013 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher, Cornell University Press. Our special thanks also goes out to Fr. Thompson for his help.