Medieval Lent was onerous, too difficult for us moderns to imagine—bread, beer (basically liquid bread), and vegetables for 40 days for all people. Peasants especially are supposed to have been durable, hard-knuckled folks who embraced the light yoke of fasting as a necessary part of the rhythms of liturgical time. Underlying each epoch, after all, is what Fritz Bauerschmidt has called a “metaphysical image,” that is, some metaphor that defines it, shapes it such that it produces specific sorts of people, rooted in specific values.[1] On this reading of medieval Lent, tradition is not merely something handed down; rather, it is something to which we look in awe—pristinely pious, dedicated, a measuring stick for our own inadequacies and misgivings. An article on one website says it all: “Think Lent is Tough? Take a Look at Medieval Lenten Practices.”

When a topic becomes clickbait, it is safe to say it is an embedded part of Catholic consciousness. In its way, this perspective has led to something of a cottage industry of Lenten repentance. There was, until only a year or two ago, Live the Fast, an organization dedicated to baking and providing filling bread so that the faithful could undertake bread-and-water-only fasts for Lent (and presumably at other times during the year). Other still existing groups encourage their supporters to concentrate on getting rid of anything but bread and water on certain days of the week. Even these, their practitioners realize, are nothing by comparison to the burden accepted by our tough medieval forebears:

We can learn much from our Latin ancestors’ observance of the Lenten Quadragesima and perhaps follow their example; if not entirely in practice, at least in spirit . . .Ash Wednesday and Good Friday were “black fasts.” This means no food at all.

Other days of Lent: no food until 3pm, the hour of Our Lord’s death. Water was allowed, and as was the case for the time due to sanitary concerns, watered-down beer and wine. After the advent of tea and coffee, these beverages were permitted.

No animal meats or fats.

No eggs.

No dairy products (lacticinia) – that is, eggs, milk, cheese, cream, butter, etc.

Sundays were days of less liturgical discipline, but the fasting rules above remained . . .Beyond the daily penances, the Triduum was more severe than even the “Black Fast” mentioned earlier. The Good Friday fast began as early as sundown on Maunday Thursday, lasting through the noon hour on Holy Saturday—when the early Church performed the Easter Vigil.

As hinted above, this entire contemporary mindset presupposes a specific relationship to time: the past, specifically the medieval past, is that which castigates us, prods us on to spiritual (and in this case perhaps even physical) betterment. It stands not only in contrast to the decadent present but also works as a corrective to it, as a sign of the true metaphysical image we need to recover to heal ourselves of modern bloat and rot.

It is, of course, true that many of these rules were on the books, and that medieval Lent was difficult. It is also true that, there is no intrinsic harm in desiring to appropriate these practices for ourselves, to accept them as traditiones, those things that are handed down. And yet, there is a danger. As one young Catholic reporter has written about her attempt at adopting these practices: “While it might seem like a hot new trend, fasting . . . ” Much hangs on that “while.” Our medieval forebearers, even more than they fasted, worried about attachments to practices that either made those spiritual exercises dry or into a sort of idolatry. We risk mistaking form for content when we make a commodity, or at least a trend, out of fasting; we risk turning an act of repentance, of metanoia, into just another thing done, and done well, that must make us better people, that must enrich us in the Spirit. There is also the risk of pride. As a Ruthenian Byzantine Catholic, I can say from experience that the stricter fasting practices of the East are not exactly a deterrent to advertising one’s spiritual prowess. In fact, the risk seems all the greater.

What I propose, then, is a quick detour through the history of Lent, specifically medieval Lent. On the way, we will see that, for our pious (and even impious) ancestors, the season was about structuring time not as castigation, but as an ebbing and flowing rhythm, one that fluctuates openly between joy and near despair. Lent was a “between” time, an eschatological one in many ways as much about the future as the past. And, while they certainly had their problems, we might say that this outlook, this understanding of time, is what we really could use to learn from medieval Lent.

As a way of curing ourselves of the all-holy image of medieval Lent, I would like to introduce le dimanche des brandons, a French folk festival celebrated on the first or second Sunday of Lent. It had many forms, but most involved frantic running around, torches in hand, with threats spewed at mice and other rodents, and pleas for fruitfulness directed at the crops. Little wooden crosses, framed with straw, were often lit on fire to accompany this celebration. As far as we can tell, the feast seems to descend from either pagan folk customs related to purification and bountifulness or the Roman Palilies, also a cleansing rite.[2] One chant, common in Berry during the festivities, gives us an idea of its play and, perhaps, its irreverence:

Come forth, mice, or we will burn your teeth. Let our grain grow. Run to the homes of the curés, for in their cellars you will have as much drink as food.[3]

First, we might notice that the emphasis is on fecundity, on having enough. This might be because fasting has just begun, or it might reflect the desire of the people, largely poor people, for food, for successful crops, as these determined whether they would live or die. The last line of the song is the most curious because of its anti-clerical bent: “Curates have all the food: why take any from us poor folk?” Not only do they have victuals but they also have alcohol, which, while mostly permitted during Lent, is not meant to be drunk to the point of intoxication. If these parsons have so much, we might imagine they are abusing their stores. If the Eucharistic wine is meant, then the people are chanting: “better it be drunk now, before it’s the Blood of Our Lord than you take our food!” Either way, this all does not seem very Lenten.

These celebrations included dancing and balls. In some regions, young people would impersonate satyrs and fauns. Such was the debauchery that the day came to be known as dimengé dei salvagi, or “the Sunday of savages.”[4] Raucous chanting, nude boys jumping over fires, young women using ashes, made from holy water and the fire, in the hopes of finding a husband—all of these were a part of the first (sometimes second) Sunday of Lent in medieval and post-medieval France. Things got so bad that some bishops felt the need to suppress the celebrations. This edict, for example, comes from the Bishop of Autun in 1750:

We desire to abolish several customs established in many locations of our diocese, of celebrating the first Sunday of Lent with fires commonly called bordes or brandons, which besides profaning the sanctity of the season by superstitious amusements, serve as an occasion for debauchery, quarrels and criminal liberties, and about which we have heard many complaints. We forbid all persons of whatever quality, condition or age to participate in or to be at the site of the said fires and ceremonies under penalty of privation of the sacraments.[5]

This was in 1750, however. The French Revolution was on the horizon. This implies that these festivals were remarkably durable. They managed to remain popular throughout the Middle Ages and into the 18th century. In fact, it is only with the emergence of the state as an absolutist institution that we see the suppression of this celebration and other folk customs like it; [6] modernity means levelling, including for Lent. French peasants, we may infer, did not see some sort of unbridgeable gap between these debauched festivities and their work of fasting during Lent. It might even be that the things that made the season easier for fasting for medieval Catholics also made it easier to keep on with these odd rites. Who wants to be the only one to eat meat in front of the community? Who is going to cook food that breaks the rules when the whole community is watching? Who cares about eating meat when you almost never eat meat anyway? Who would not jump over the raging fire to celebrate the purification of the crops?

So, medieval Lent is complicated—fair enough. But what did it actually mean to medieval people? If it was not all sorrow and black fasts, scourging and sourness, what was it? The answer is necessarily too complicated for an article of relatively-brief length, but a glance at specific text or two might allow us to make certain observations that cut against the prevailing, commercializing narrative that has come to mean so much to so many Catholics.

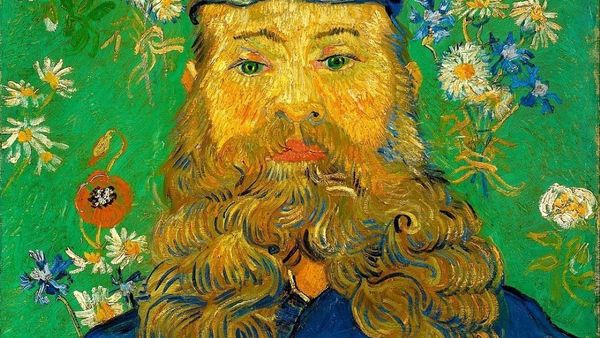

The late 13th century La Bataille de Caresme et de Charnage (The Battle of Lent and Carnage) is a play that foregrounds the complex relationships among periods of liturgical time in the Catholic imagination. The Carnival figure is a baron, loved by everyone, liberal with gifts, and generally shown to be a good ruler, one under whom a serf or seneschal might want to labor. Lent, by contrast, is depicted as a hypocrite. He takes advantage of his connections with rich abbeys and monasteries to oppress the poor, denying them food and basic subsistence while glutting himself.[7] We should beware being too simplistic here: it is not Lent itself that seems to have disgusted people, but rather the way it was enforced. Punishments for eating meat included the removal of teeth, caning, and whipping.[8] And all of this went on while many churchmen enjoyed immense wealth, affording them great personal luxury. Here we might hear echoes of the song sung to the mice by French peasants on the first Sunday of Lent—curates had basements filled with food and drink!

We can observe similar trends in the Italian texts Il Gran Contrasto e la sanguinosa Battaglia di Carnivale e di Madonna Quaresima (The Great Contest and the Bloody Battle of Carnival and of Lady Lent) and Rappresentatione e festa di Carnovale et della Quaresima (The Performance and Feast of Carnival and Lent).[9] The people seem to have detested the hypocrisy implied in the way the Church observed Lent: meat for me, but not for thee.

Of course, Lent remained necessary. Eva Kimminich calls her, as a figure in these medieval texts, a “necessary evil.”[10] The point is not that medieval peasants thought Lent was bad, or simply contingent; in fact, it stood as a central part of the liturgical year. Therein lies its significance. So many of the debates about medieval popular culture go back to Bakhtin. Perennially, we ask: were the people really religious? Did they simply use these festivals and plays as ways of getting around restrictions? Who can actually believe? Neil Cartlidge, after surveying the material, has this to say:

Not only are these texts relatively undogmatic in themselves: they are also too varied to underwrite any dogmatic reading of the Middle Ages. Moreover, they all present Shrovetide as an empirical event—an occasion, that is, repeatedly subject to change and reinterpretation, rather than an idea fixed in some kind of cultural memory, before and beyond the pressures of experience. In this way, they effectively illustrate the irrelevance of several of the controversies central to current studies in late medieval culture—such as the question of whether “carnivalesque” practices were essentially and significantly subversive or merely served as a kind of safety-valve for dissent. The problem with such a question is not that the historical evidence is so varied, but that by taking a consciously historical perspective in the first place, it effectively closes the debate even before it has started. The literary tradition of depicting Carnival-against-Lent, by contrast, depends on the irresolvability of such questions, for it is precisely in competing possibilities of this kind that writers and artists found material with which to work.[11]

All we can say definitively is that these customs existed side-by-side, and that they, by way of festivals and dramatic performances, captured the polychrome of Catholic liturgical time. Carnival and Lent require one another; neither protests the other. Each stands against hypocrisy, echoing Christ’s inveighing against religious authorities, the whited sepulchers, reminding us of the Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican.

Obsession with exterior practices is what gives us the hated, “necessary evil,” Lent, found in certain texts; she reflects a Church crying “do as I say, not as I do!” Folk festivals became one way of crying out against such uncleanness within the Church. Literary personifications were another. “How dare you threaten to remove my teeth for eating meat, when we know that your basement is stocked?” What good is to follow the rules of fasting without love in one’s heart? The celebrations before Lent presage the celebrations after it; the deprivations of Lent do not merely remind us of our mortality. They signify the comings and goings of time, pointing toward eternity, toward the new heaven and the new earth we expect. What is done here matters in that great, “eternal tomorrow.” Both our fasting and our feasting will be recorded in the book and reported to us before the fearsome judgment seat of Christ. Lent without joy is not Lent; Carnival and Easter without repentance are meaningless. The Desert Fathers already knew this:

It was said about an old man that he endured seventy weeks of fasting, eating only once a week. He asked God about certain words in the Holy Scripture, but God did not answer him. Then he said to himself: “Look, I have put in this much effort, but I haven’t made any progress. So now I will go to see my brother and ask him.” And when he had gone out, closed the door and started off, an angel of the Lord was sent to him, and said: “Seventy weeks of fasting have not brought you near to God. But now that you are humbled enough to go to your brother, I have been sent to you to reveal the meaning of the words.” Then the angel explained the meaning which the old man was seeking, and went away. Along with fasting there must be humility! Fasting opens the way; it is a means to an end; it is not the end itself.

If Lent is the destruction of hypocrisy, it is also always about the eschaton. To hold the past over us as a whip, to force us toward a better future (and this is how we tend to see medieval Lent) inverts what the season means. It teaches us to look forward to joy eternal, separated from all hypocrisy and hate. We might say that liturgical time, Lent included, enacts what Jürgen Moltmann has said about eschatology: “True eschatology is not about future history; it is about the future of history.”[12] Avoiding hypocrisy means living not through the idolization of specific practices but through the call to bring forth the Kingdom of God. In this sense, Lent is always future oriented even as it looks back to the pleasures of Carnival.

It grants us, even if only for 40 days, a foretaste of the Kingdom, a glance at what is ultimately important. In seeing medieval Lent as something complicated, enforced by social norms not available to us today, celebrated in ways more debauched than even those found yearly on the streets of New Orleans, we begin to understand the mission of the Church and its traditions more fully. We begin to recover the fact that our practices are always geared toward the eschaton; if commercialization risks hypocrisy (as it did, in its infant stage, even in the Middle Ages), recalling this complex history leaves us nothing to lose, but everything to gain.

None of this is to say that we should not fast better, or that it is a bad idea to look back to the medieval period for ways of better mortifying ourselves. It is merely to say that Lenten fasting must always be directed at the future, our future and that of the Church, and not merely at some impossible recovery, seeking something that never was. There is nothing for us in searching within some of the white sepulchers of history.

[1] Julian of Norwich and the Mystical Body of Christ (South Bend: 1999), 12.

[2] Holman, Robyn A, “The First Sunday of Lent: Its Origin and Celebration in Medieval France,” (Medieval Perspectives, 12:1, 1997), 102.

[3] Ibid, 103.

[4] Vloberg, Maurice. Les Fêtes de France: coutumes religieuses et populaires (Grenoble: 1936), 41.

[5] Holman, 108.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Kimminich, Eva, “The Way of Vice and Virtue: A Medieval Psychology,” (Comparative Drama 25:1, 1991), 190-191.

[8] Ibid, 191.

[9] Ibid. 193.

[10] Ibid, 194.

[11] “The Battle of Shrovetide: Carnival against Lent as a Leitmotif in Late Medieval Culture,” (Viator, 35:1, 2004), 541.

[12] The Coming of God: Christian Eschatology (Minneapolis: 2004), 10.